The weak yen is an opportunity

So why can't Japan take advantage of it?

When I first lived in Japan in the mid-2000s, it was very easy to remember how much a yen was worth — it was just about 1 cent. You’d just divide all the Japanese prices by 100 in your head to get an idea of how expensive anything was.

That rough 100-to-1 exchange rate held, more or less, for about three decades. Then in March 2022, something broke. The yen began to fall, briefly sinking below 150 to the dollar in October before rallying a little to 140:

The country’s broad real exchange rate has also fallen relative to its trading partners.

This drop has caused a lot of consternation in Japan. In fact, the reason the yen bounced back up a bit was that the Bank of Japan intervened, buying a suspected $37 billion worth of yen to support the currency’s value (the exact numbers aren’t released).

This was all big news in Japan, and a lot of people there were freaked out. As for me, I think there’s a more important story here — a weak currency can be a big opportunity for a country, and the fact that Japan isn’t taking that opportunity points to important problems with its current economic model. But before I explain why I think that, let’s go through the basics of why the yen got so weak, why the BoJ intervened, and how intervention works.

How this all (basically) works

Generally, things get cheap when demand for them drops. So the reason the yen suddenly went from ~100 to the dollar to ~150 to the dollar is because suddenly, fewer people wanted yen. And it’s not hard to see why — it’s because of interest rates.

Inflation is high in most places, including the U.S., so central banks all over the world, including the Fed, have been raising interest rates. Japan is the big exception. The country spent decades slipping in and out of deflation, which was quite harmful for the economy (for reasons I won’t go into), so they’re actually happy to get a little bit of inflation. The BoJ is more afraid of causing unemployment. So Japan has stuck to easy monetary policy, keep rates right around zero even as everyone else has hiked.

Now suppose you’re a bond investor. You can buy U.S. government bonds, which are super-low-risk and pay 3.83%, or you can buy Japanese bonds, which are also super-low-risk and pay 0.10%. This is kind of a no-brainer, right? You buy the U.S. bonds. To buy those bonds, you’ll need U.S. dollars. So the interest rate differential makes demand for dollars go up (to buy U.S. bonds) and demand for yen go down (since no one wants to buy Japanese bonds), so the dollar gets stronger and the yen gets weaker.

Another big reason you might want yen is to buy Japanese goods. But people haven’t been doing as much of that lately. Japan used to run a trade surplus all the time, but now they’ve been in and out of a trade deficit for the last decade. And recently they veered way into the red:

So between low interest rates and low net exports, demand for yen went down, and so the yen got weaker.

Now, the Bank of Japan doesn’t want the yen to get to weak, for a number of reasons. A weak yen makes it harder for Japanese manufacturers to buy the components and materials they need to stay competitive, for one thing. Even more important, Japan is a country that imports a ton of food and fuel, without which the country can’t really run at all. So a weak yen can be very dangerous — you don’t want to become Sri Lanka here. Thus, the BoJ intervened to keep the yen from getting too weak.

How did the BoJ intervene? It increased demand for yen by swapping dollars for yen. And where did it get the dollars? From its gigantic pile of dollar assets, also called foreign exchange reserves. During all those years that Japan ran trade surpluses, it was building up forex reserves, and now has over $1 trillion. So it just sold some of those U.S. bonds for dollars and used those dollars to buy yen, thus propping up the yen.

Now, a country can’t get away with this kind of thing forever. Eventually you run out off dollar reserves, and then your currency crashes and you have a big economic crisis. But $37 billion is only a small fraction of $1.2 trillion, so the BoJ can keep this up for a pretty long time if it wants. And right now, traders are basically keeping the yen in the 140s because they’re afraid that if they sell it off, the BoJ will intervene more and they will lose out. So the BoJ doesn’t need to constantly sell more and more dollars to prop up the currency — it just has to be able to credibly threaten to do so.

So that’s where we are now. The situation is stable, but there’s still the danger that traders might decide to sell off the yen some more. Japanese policymakers are quite worried about that. But at the same time, they seem to be ignoring the opportunity that a weak yen presents.

A weak currency should boost exports

This is the first time Japan has intervened to prop up the yen since the Asian financial crisis of 1998, but it has intervened to weaken the yen many times over the past two decades. Why? Because a weaker real exchange rate is good for exports. Japan needs to export in order to survive (since it imports food and fuel), and it helps if its companies maintain their market shares in international markets. The BoJ doesn’t want the yen to get so weak that Japan can’t afford imports, but it also doesn’t want the yen to get too strong so that people stop buying Japanese goods, because this will also eventually lead to Japan not being able to afford imports. For many years, Japan wanted to run a trade surplus — unlike the U.S., which was pretty much fine running large trade deficits.

So the recent weakening of the yen could actually be a boon to Japan. It could put more Toyotas in people’s driveways, more Kioxia memory chips in people’s computers, and more Sony TVs in people’s living rooms (and just maybe, more anime on those TVs as well).

But so far, this is just not happening. Japanese exports have risen in yen terms, but that’s just because the yen is worth less. In dollar terms — which roughly reflects how much imports Japan’s exports allow it to buy — the country’s overseas sales haven’t really budged:

As you can see, this continues a trend that has held since 2008. Japanese exports, which had risen for decades upon decades with just a brief pause in the late 90s, have flatlined or declined since the global financial crisis.

In fact, the government is aware of the opportunity that the weaker yen presents. Prime Minister Kishida Fumio recently pledged to use government subsidies to help Japanese companies export more:

We’ll see if this works. But the longer-term trend here — and the very fact that exporters would need subsidies, beyond the cheap currency itself — is a bit discouraging. The fact that Japanese exports are not surging in response to a weak yen the way they used to suggests that the flatlining of exports 2008 is due to structural changes in the Japanese economy.

Japan’s structural exporting weakness

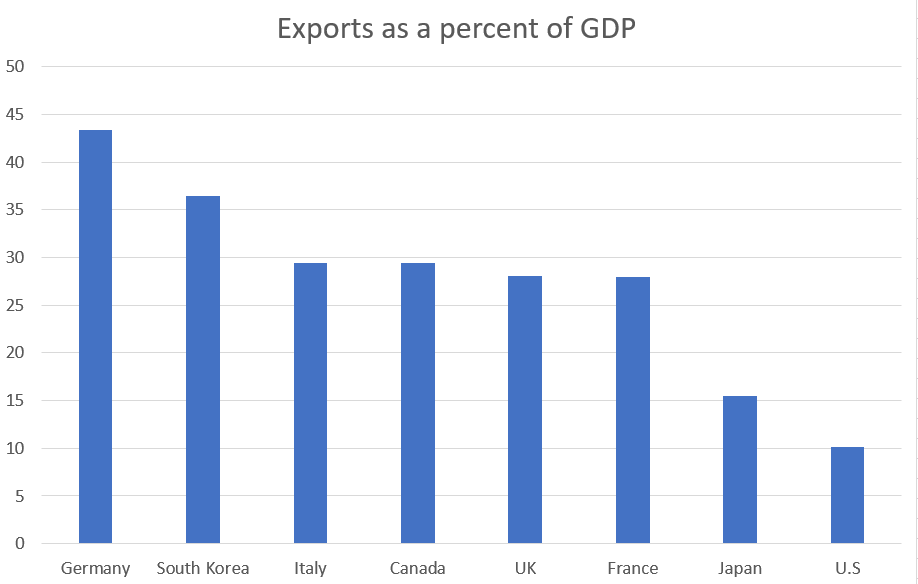

A lot of people traditionally stereotype Japan as an export-intensive economy, but this isn’t really true, and it was never really true. Exports are only 16-17% of GDP in Japan, which is not very high in an international context:

Part of the reason is that Japan has a large domestic economy, which tends to reduce the relative importance of exports. But Germany, whose economy is almost as big as Japan’s, sits at a whopping 47.5%. Even China is at 20%. So Japan is just not as good at exporting as it could be.

What’s the problem? Well, the basic economics of comparative advantage says that when other countries enter the global trading system that have similar strengths and weaknesses to your country, you tend to lose out — basically, your niche gets more crowded. Japan’s most important exports are automotive products, electronics, and machinery. And the rise of South Korea, Taiwan, and (especially) China has cut into Japan’s uniqueness. Samsung and LG compete directly with Panasonic and Sony, for instance — as do Chinese brands like Hisense. Taiwan and China’s laptop manufacturers have made life difficult for their Japanese rivals. Hyundai competes in autos, and so on. In the 2000s, Japanese exporters profited off of China’s rapid rise, by selling valuable components and machinery to rapidly expanding Chinese companies. But that boom came to an end when China’s economy matured and its leaders started trying to move up the value chain.

That said, however, South Korea and Taiwan — which are now as rich as Japan — have continued to be export powerhouses even in this challenging competitive environment.

How about basic input costs? Japanese wages are very competitive at this point, and electricity costs are only moderately high (much lower than Germany).

Honestly, no easy explanation comes to mind. The people who’ve written about Japan’s exporting weakness over the last decade generally talk about macro factors; but many of those factors have since reversed themselves, and macro doesn’t explain Japan’s small baseline level of exporting. Basically, this is a mystery.

It’s tempting to turn to fuzzier explanations like management, corporate culture, industry structure. These things are hard to measure, and hard to change. But they might be a factor here. One such factor might be the traditional importance of trading companies — called sōgō shōsha, or 総合商社 — in Japan’s economy. In 1983, if you were a Japanese brand and you wanted to sell stuff overseas, you would go to one of these big companies and ask them to market it for you. But these middlemen were very expensive, and over time they lost their knack for selling overseas; at this point, they’re basically just private equity companies. But perhaps as a lingering result of trading companies’ long era of dominance, many Japanese companies have not really developed a culture of looking for business overseas.

Another problem is Japan’s tendency to develop technical standards domestically, without an eye to what the rest of the world is doing — something the late Devin Stewart called “Galapagos syndrome”. An early example was the mini-disc players that Japanese companies thought would replace compact discs, but which ended up being forgotten in an era of digital audio. But a far bigger and more consequential example is the country’s failed experiment with hydrogen cars.

Hydrogen is very promising for some applications, but for cars it’s just not economical. Yet big Japanese car companies spent years trying to make hydrogen happen, instead of jumping on the battery revolution like their international rivals. As a result, big Japanese automakers like Toyota, Honda and Nissan are forecast to have fewer than a quarter of their vehicle fleet be zero-emission vehicles by 2029, while for German automakers Mercedes-Benz, VW, and BMW that number is around half. Now Toyota is left in the pitiable position of trying to market its venerable Prius as “an EV with an engine”. Nope.

Why are Japanese companies going from stumble to stumble, where in the 70s and 80s they seemed to go from strength to strength? Some will blame the lack of a firm guiding hand from the state, due to the weakening of Japan’s legendary trade ministry. But by the 80s, Japan had already begun to lose competitiveness in electronics — a trend that has sadly continued to this day. To some degree, weak export competitiveness might simply be an extension of Japan’s broken corporate culture — seniority-based promotion practices, along with extreme population aging, have made Japanese companies top-heavy with stodgy old men who want to run comfortable little declining corporate empires instead of adventuring into new overseas markets.

Whatever the problem is, Japan’s policymakers, academics, and corporate managers need to start viewing export weakness as a matter of urgent national importance. In the 90s, exporting was optional; now, it is not. Japan’s population is aged and shrinking, which limits domestic market opportunities, even as the country is still dependent on imported food and fuel. If it’s going to avoid both long-term stagnation and vulnerability to currency drops like the recent one, the country must become more of an export powerhouse. Hopefully the weak yen can provide the impetus and the inspiration for Japan to get serious about this.

I agree it's weird. Back in early 2000s when I first went to live and work in Japan I picked the place because it was (still) seen as cool and cutting edge. The newest technology, the craziest big city culture, anime, video games, movies, J-Pop. And then all that stopped sometime in last 5-15 years. I still remember being kinda shocked realizing circa 2007-08 that Samsung now made better TVs than Sony. Part of this is I agree due to poor corporate culture (it should not be forgotten that a lot of the corporate titans of post-war Japan were led by mavericks, and the system subsequently put in place of lifetime employment, seniority based promotion system, hierarchical desirability ranking of companies from big to small etc. really made repeating that trick very difficult). My own experience working at the R&D center of one of their big electronics conglomerates made it very clear very quickly that despite the vast resources being deployed no real innovation was ever going to come out of there.

But what about something like J-Pop (cool in early 2000s) being utterly supplanted in global consciousness by K-Pop? Even if K-Pop is arguably more an industrial than an artistic product and so maybe also subject to corporate culture differences, am still befuddled by why latter overtook former so completely.

Excellent article. There was a section on a lack of Japan bringing their products to other nations to promote exports. I have worked in the Sourcing departments of major US manufacturers (industrial goods, pharma, and medical device) for the past 10 years. My job is to find manufacturers of items we need. For large US businesses, demand for parts and finished goods is a process of seeking out vendors to make custom items. In my experience, Japanese companies were absent or not focused on the main marketing platforms for international business-to-business sales (Alibaba, Thomasnet, Pharmacompass). When you can find a Japanese company online, more than 75% do not have an English version of their webpage which makes getting an idea of a companies technical prowess dependent on Google Translate. This is opposite of Chinese companies. They are hyper present on these platforms and they have English versions of their websites. This makes it super easy to do business with Chinese companies.