At least five interesting things for your weekend (#48)

Information war; Chinese VC; land reform; India's garment industry; degrowth research; Trump vs. Harris on deficits; good news

Well, I’m back from my travels in Europe, and ready to send a whole bunch more Noahpinion content your way! There’s a whole lot to catch up on, so let’s start with a slightly long roundup post.

First, podcasts! Erik Torenberg and I talked to Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, about the economics of AI:

Dario is an awesome guy (and reminds me oddly of my PhD advisor Miles Kimball, whom I hope to someday introduce him to). Anyway, the video for this one is pretty fun too:

And Erik and I have another episode of Econ 102 out as well — a “mailbag” episode where I answer a bunch of questions.

Also, this isn’t a podcast, but I did get interviewed for the Polish website Money.pl. It’s in Polish, but Google Translate is getting really good these days.

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. The U.S. is starting to realize that we’re losing the information war (badly)

Last year I wrote one of the scarier posts I’ve ever written, about how liberalism is losing to totalitarianism in the global information war:

My thesis is that liberalism is losing because, in effect, it has refused to fight — liberal countries decided that our own governments were omnipotent leviathans who must be forever kept away from the arena of speech, while foreign governments are simply one more kind of atomistic “private” actor whose rights are never to be infringed. If the government of China controls our information diet, we decided, that is freedom, while if the government of America dares to push back, that is oppression.

I think we’re now just starting to realize how badly this idea has cost us. The U.S. Justice Department has just indicted a group called Tenet Media — which sponsors a bunch of big-time right-wing podcasters on YouTube — for “covertly funding and directing” the Americans who worked for it, publishing videos “in furtherance of Russian interests”.

The podcasters in question include Tim Pool, Dave Rubin, Benny Johnson, and Lauren Southern — all prominent pro-Trump right-wing firebrands. Rubin and Pool apparently made the most money from Tenet.

Only time will tell how much each media figure knew that Russia was trying to manipulate them (unless Trump gets elected and kills the investigation, of course). And we don’t know how effective Tenet was in getting right-wingers to say pro-Russia things, or how effective those messages were in swaying American public opinion.

But what this case does show is that foreign governments’ attempts to manipulate Americans’ opinions are far more extensive than most people realize, and that our government’s process for finding and countering them is very slow and cumbersome. Yes, we fought back this time —belatedly. But it took us a very long time to do so, and even this one effort may eventually get canceled. The many long years in which we accepted foreign government propaganda as “private” speech have probably made us hesitate either to investigate it when it does break the law, or to even believe that it might be worth investigating.

In fact, we’ve probably just scratched the tip of the iceberg. The FBI recently reported that the Russians have 600 “active influencers” in America, but has not released the list. The Tenet indictment names only two such influencers. Meanwhile, a former aide to New York governor Kathy Hochul was just arrested for being a Chinese spy. Given that she was just about the most blatant and obvious spy ever, it’s fair to say she’s probably far from the only one working in American politics.

What do the totalitarians want Americans to think? Most of Russia’s efforts seem to be supporting Trump and opposing Democrats. That’s unsurprising, given that Trump is far more pro-Russian than Harris, and probably plans to force Ukraine into ceding territory to Russia (or worse). But more fundamentally, the goal of the totalitarians seems to be to sow chaos and division in American society. The weaker America is internally, the less it will be able to oppose China and Russia on the international stage.

Fortunately, I think cases like Tenet Media are causing Americans to — very slowly — wake up and realize that the information war is a war, and that they are losing that war. Jeremiah Johnson has an excellent post explaining why we should all be more worried about foreign governments’ attempts to control our media:

And the Foundation for Defense of Democracies just released an excellent report entitled “Cognitive Combat”, where they make arguments similar to those I’ve made, but in much greater detail.

My main worry at this point is that the election of Trump this fall will plunge America back into another four years of bitter social strife, distracting and delaying us from even being able to start fighting back in the information war.

2. China’s VC-funded startup sector collapsed

I’m not a China expert, but occasionally I get something right. Back in 2021 I wrote a post called “Why is China smashing its tech industry?” that got a lot of attention:

The basic thesis — which government documents later confirmed — was that Xi Jinping sees sectors like IT, finance, and education as not being “real” innovation, in the sense of not contributing much to China’s national power, and wanted to force resources (engineers and capital) to shift from those sectors toward manufacturing.

In 2023, as it became clear that China’s real estate bust was going to hurt the economy, a lot of stories came out about the government backtracking on the tech crackdown. And yet this always seemed to me a bit like wishful thinking, given Xi’s resolute focus on his vision of China; he doesn’t seem like the kind of guy to flip-flop on his big vision just because some econ nerds tell him that GDP needs to go a little higher.

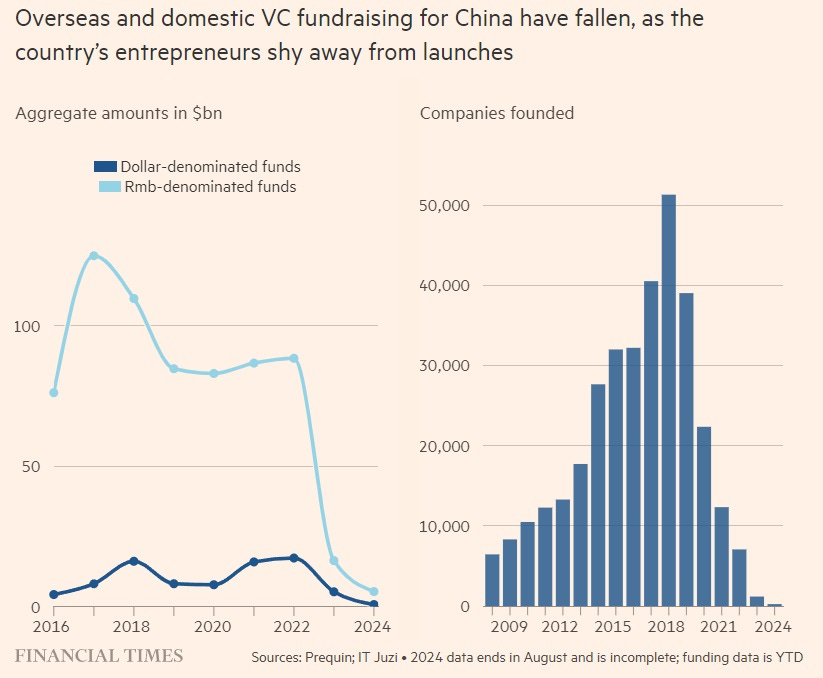

Now we have an eye-opening story in the Financial Times, detailing just how bad things continue to be for the Chinese tech sector. Here are some charts:

The article has tons of good quotes and anecdotes from extensive interviews with people in the Chinese VC/startup sector, but here are just a few short excerpts:

[A] wave of failures has led VC firms to try to claw back assets from their insolvent investee companies through the courts…VC firms have laid off investment professionals and in some cases replaced them with lawyers or former judges to enforce the repayment terms…

Foreign investors, wealthy Chinese, and corporate investors have been divesting or reducing their exposure to China, leaving state-backed players with an outsized role… [S]tate-run funds now accounted for around 80 per cent of capital in the market…Limited partners are also increasingly requiring fund managers to guarantee returns, creating a bias towards lower-risk investments…

Several firms say they are now mostly looking at companies in manufacturing, regarding them as less risky. In 2023, advanced manufacturing companies working on new energy, integrated circuits and new materials accounted for over 30 per cent of start-ups founded, according to IT Juzi — a marked change from previous years, when biotech, consumer technology and education topped the charts…Financing for biotech and pharma start-ups fell by 60 per cent in 2023 from its 2021 peak of Rmb133bn…While a funding chill has hit most areas of tech, several venture capitalists mention humanoid robots and electric flying vehicles as two areas gaining traction, after Beijing singled them out for support in recent policy documents.

This is 100% consistent with my thesis that Xi’s personal vision of national power is driving the trends in the Chinese tech sector. One interesting new tidbit here is that biotech seems to be getting neglected too, which is consistent with Xi’s seeming disinterest in giving China a better health care system.

The overarching principle here is that anything that a conservative Baby Boomer imagines would lead to greater military power is going to get supported, while anything that a conservative Baby Boomer thinks would lead to a happy but lazy and decadent populace will get squashed. Essentially, I believe that “conservative Baby Boomer with too much power” is the right way to model Xi.

Whether Xi’s intuition actually leads to national power is still unknown. The coming decades will be a test of his vision.

Update: China boosters were quick to question whether the FT’s data was complete and accurate. But recent data from Pitchbook also shows a big collapse in Chinese VC activity:

Chinese startups have raised just $26 billion so far in 2024, according to data provided to Axios by PitchBook. That's more than an 82% decline from the 2021 peak, and less than 50% of any year over the past decade…And this isn't only about decreasing valuations. Deal counts are halved from just last year…Much of the fall is indeed due to foreign investment drying up — a meager 19% of the money into 6.9% of the deals so far in 2024 — but that doesn't account for nearly all of the decline.

3. Was Joe Studwell wrong about land reform?

As long-time readers of my blog know, Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works is my favorite popular book about industrial policy and economic development (and generally one of my favorite books of all time). But that doesn’t mean Studwell got everything right. In fact, in 2021 I wrote post criticizing him for ignoring PPP adjustment (which caused him to overrate South Korea’s development relative to Taiwan’s) and for neglecting Malaysia’s success in the electronics industry:

Now, a smart new paper in development economics claims that one of Studwell’s central claims is overblown. Studwell attributes much of South Korea and Taiwan’s successful development to land reform — the forcible purchasing of farmland from landlords and its redistribution to tenant farmers. In Studwell’s telling, this land reform program — which in Taiwan went by the name of “land to the tiller” — had positive effects on growth through a number of economic and political channels. He believes:

Land reform increased agricultural yields, because farmers would work the land more intensively if they owned it

By helping small farmers out of debt and by giving them the ability to sell their land for cash, land reform enabled them to leave the farms and move to the cities to work in manufacturing

By forcing landlords to trade land for cash, land reform incentivized them to go start more productive businesses in export industries

Because land reform is labor-intensive, it absorbs surplus rural labor and gives people something to do, leaving fewer idle frustrated people to rebel against the government, which in turn fosters political stability

Land reform acts as a vaccine against communism, increasing political stability

That’s…quite a lot of potential channels for land reform to have an effect!

Anyway, much of the debate around Studwell’s thesis focuses on the first of these — the idea that land reform increases agricultural yields.1 The basis for this claim is the finding that very small farms often have higher yields per hectare than medium-sized farms. There’s a surprising amount of evidence in favor of that proposition, though no one knows exactly why it holds. But given that tiny farms often have high-ish yields, it makes sense to think that land reform, which breaks medium-sized traditional farming estates into many tiny self-owned plots, would increase yields overall.

Not so, says a new paper by Oliver Kim and Jen-Kuan Wang! Basically, the economists go back and digitize a bunch of old Taiwanese records, and then just look at the correlation between Taiwan’s land reforms and changes in agricultural yields. For “phase III” of the land reform — the part Studwell praises the most, which broke up big estates and distributed the land to tenant farmers — they find no correlation at all between land reform and changes in yield. In other words, no effect at all. One of Studwell’s arguments for land reform now looks a lot shakier (though of course we need more evidence on the topic).

Critics of Studwell immediately pounced and declared that his thesis about land reform had been debunked. Not so. As Kim and Wang note, their paper casts doubt on only one of the five channels by which Studwell believes land reform helped Taiwan. In fact, it provides support for one of Studwell’s other channels — the idea that land reform causes an outflow of labor from agriculture to manufacturing:

[I]t was phase III [of land reform] that had the strongest local effects on industrialization—but, it appears, by pushing surplus labor off of plots that were too small to be economically viable…phase III pushed women into manufacturing, while producing no discernible effect for men…[M]uch of the increase was driven by employment in textiles.

The keen-eyed reader will note that this also suggests a possible reason why Studwell’s first channel could still be right, even given Kim and Wang’s result. If the women who left farming for manufacturing as a result of land reforms were the more skilled farmers, that could cause a composition effect that canceled out the positive effects of decreased farm size on yields.

But anyway, even though it doesn’t actually debunk the idea that land reform is useful for industrialization, Kim and Wang’s paper is a very valuable addition to our understanding of development.

By the way, Kim also has a Susbtack, which you should check out, even though he doesn’t post very frequently.

4. India needs women making clothes for big companies

Economists lack a grand unified theory of development. Thus it’s probably best for a poor country to try a multi-pronged approach to try to raise GDP, instead of settling on a single “growth model”. Usually, a country’s “growth model” only becomes visible in retrospect — it’s a summary of which approaches worked, rather than a theory that was followed from start to finish.

India’s generally doing a decent job at the “try a bunch of stuff” approach. Very frequently now, I see news about good things India is doing — expanding port infrastructure, building up the semiconductor industry, etc. But there are always some new things to try!

One idea is to build a world-class garment manufacturing industry. Making clothes is a sector of manufacturing that’s still very labor-intensive, and so can provide a ton of jobs. Mass labor-intensive garment manufacturing helps teach the bulk of the populace how to work in factories, which then helps prepare them for work in higher-value-added industries like electronics and autos. Bangladesh has done an incredible job building up its garment industry, so there’s no reason India can’t do the same. Menaka Doshi writes:

India's apparel export industry…has missed the China+1 opportunity [so far], with Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia and even some Eastern European countries grabbing market share, while India stagnates at around 5%…And yet, a neighborhood crisis, a billionaire deal and the Modi government's latest jobs push offer some hope…

The $14.5 billion apparel export industry needs access to cheaper raw material, scale, skills and labor reforms…[A]ny structural shift needs to first address the industry's persistent problem of size…The industry has very few large, vertically integrated players that can invest capital, technology and professional management…

Archaic and complex import procedures curtail India's access to cheaper synthetic fabric, the key raw material for almost 70% of the apparel trade…India's exporters have to meticulously account for every square centimeter of fabric, buttons and zippers imported and used to avoid high import duties…Since 2017, India's tariffs have risen by approximately 13 percentage points in the textile and apparel sector…These are all challenges China overcame decades ago.

The most important thing India’s garment industry needs, though, is probably just female employees. Women are always the backbone of any garment industry; my own grandmother worked in a clothing factory when she was a teenager. Here’s what it looks like today, in Bangladesh:

And here is what it looks like zoomed out, at scale:

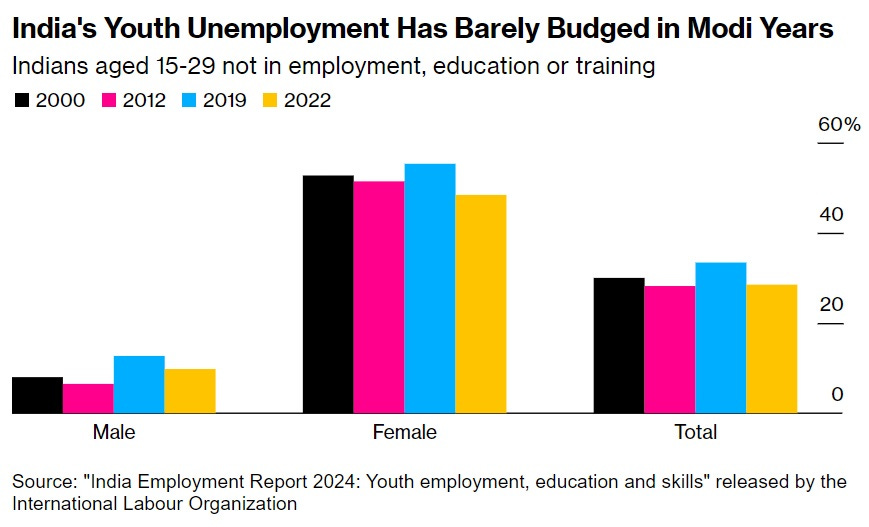

India, however, still has vast numbers of young women who aren’t working outside the home:

A lot of these women should be out working in garment factories. If a conservative Islamic society like Bangladesh can manage that social shift, then India can too!

Remember, garment manufacturing and other labor-intensive industries are not substitutes for semiconductors, autos, or any other sector. They are complements. This is just one more needed piece of India’s growth puzzle.

5. Degrowth research is low-quality stuff

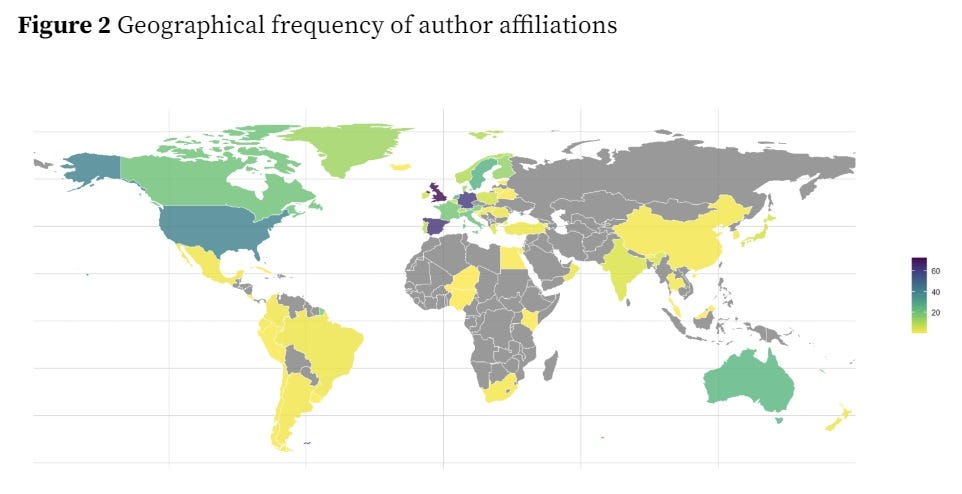

Degrowth is quasi-scientific activist discipline that has unfortunately become somewhat popular in Europe and the Anglosphere in recent years. Degrowthers will tell you that their ideas are supported by a vast scientific literature. But every time I look into that literature, I find it to be incredibly shady-looking — a bunch of papers in no-name journals that seem created specifically to promote degrowth, a blizzard of activist ideological language, and some extremely shoddy quantitative methodologies.

Now Jeroen van den Bergh and Ivan Savin have taken a more systematic look at that literature, using text mining techniques. Their results confirm my own impressions:

The large majority (almost 90%) of studies are opinions rather than analysis. Only nine studies (1.6% of the sample) use a theoretical model, eight (1.4%) employed an empirical model, 31 (5.5%) performed quantitative data analysis, and another 23 studies (4.1%) qualitative data analysis (e.g. interviews)….[T]here is no clear trend indicating that the share of studies with a concrete method is increasing…

Inspecting the 54 studies that used qualitative or quantitative data analysis, we find that they tend to include small samples or focus on peculiar cases – for example, ten interviews with 11 respondents on the topic of local growth discourses in the small town of Alingsås, Sweden (Buhr et al. 2018), or two locations of ‘rural-urban (rurban) squatting’ in the Barcelona hills of Collserola (Cattaneo and Gavaldà 2010). This easily gives rise to non-representative or even biased insights…Out of the 561 studies we reviewed, only 17 studies using theoretical or empirical modelling shed some light on these broader consequences.

Color me shocked. Van den Bergh and Savin also find that the UK, Germany, and Spain are the prime loci of degrowth research:

I maintain my position that degrowth chiefly represents an attempt to valorize national decline, rather than an attempt to conduct a serious scientific inquiry into policies for environmental improvement.

6. Trump would be worse for deficits than Harris

America is at the point where we need to be thinking about fiscal austerity. This is very hard to do politically, since austerity is hard on people in the short term — we’ve gone a long time without meaningful tax hikes or spending cuts, so it’ll take bold leadership to convince America that we need these.

Donald Trump is definitely not someone who’s going to give America the bad news. As a populist leader, promising people free goodies is a core part of his appeal. And as someone who is fundamentally very selfish, he’s unlikely to sacrifice his personal popularity for the good of the country’s future.

Kamala Harris, meanwhile, is also unlikely to engage in the kind of austerity Bill Clinton did — first, because she has to run against Trump and his irresponsible promises, and second, because the Democrats are probably still in borrow-and-spend mode from the Covid years. But because Harris is a more responsible and unselfish person than Trump, and because Democrats are more likely to listen to economists and other experts, my guess has always been that Harris would be the relatively more austerity-minded of the two.

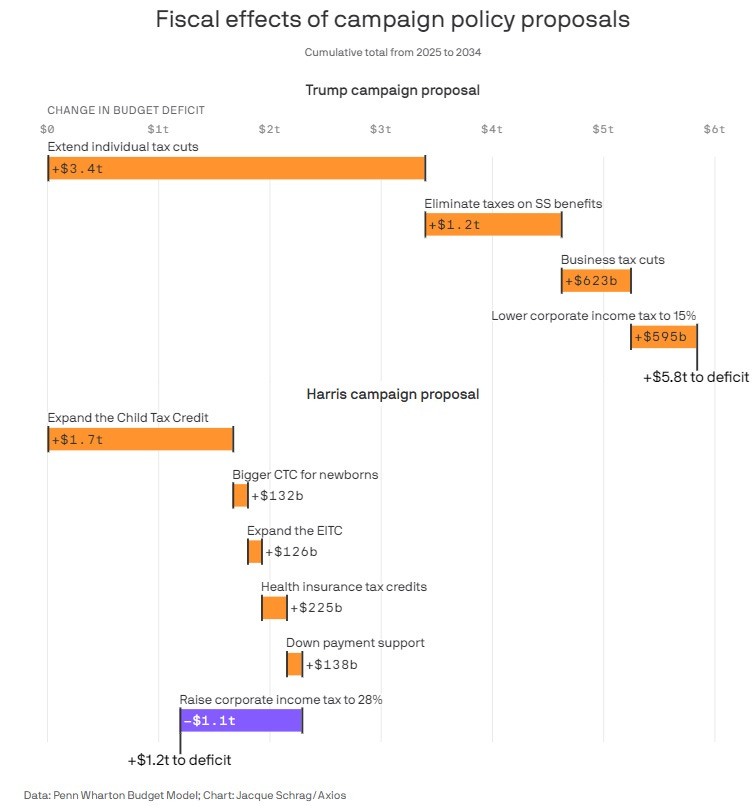

That’s my read, anyway. Now there’s some evidence to back me up. The Penn-Wharton Budget Model — an independent, nonpartisan model of budget impacts of political proposals — just released analyses of Trump’s and Harris’ fiscal proposals. Here is what they found:

Former President Donald Trump’s economic proposals would increase federal deficits by $5.8 trillion over the next decade, almost five times more than those of Vice President Kamala Harris, which would add $1.2 trillion, according to a new pair of studies from the nonpartisan Penn Wharton Budget Model.

The Trump report found that his plan to permanently extend the 2017 tax cuts would add more than $4 trillion to deficits over the next 10 years. His proposal to eliminate taxes on Social Security benefits comes with a $1.2 trillion price tag, while his pledge to further reduce corporate taxes would add nearly $6 billion.

The Harris analysis showed that her plan to expand the child tax credit, the earned income tax credit and other tax credits would raise deficits by $2.1 trillion in the coming 10 years. And her proposal to create a $25,000 subsidy for all qualifying first-time homebuyers would add $140 billion over a decade.

But the Harris report found that raising the corporate tax rate to 28% from its current level of 21%, as the vice president has floated, could partially offset the costs of her spending by $1.1 trillion…Along with corporate tax hikes, Harris has said she supports the $5 trillion worth of revenue raisers contained in President Joe Biden’s budget proposal for the 2025 fiscal year.

And here is a chart of the two plans, from Axios:

The Trump campaign is, of course, predicting A) magical growth effects from tax cuts, and also B) magical growth effects from tariff hikes. If it sounds suspicious to claim that tax hikes and tax cuts both boost growth, well, that’s because it is. In Trump’s first term, his tax cuts ended up hurting revenue a bit more than expected, while the revenue raised by his tariffs was pretty modest.

So I’m not optimistic about austerity in the near term, but I’ll be much less pessimistic if Harris wins. In other news, here’s a new paper by Hazell and Hobler that blames deficits from Covid relief spending for about 30% of the post-pandemic inflation — roughly in line with analyses I’ve seen elsewhere. So if Trump wins, there’s a possibility inflation could return.

7. Some good news

I feel like posting some optimistic charts. Did you know that overdose deaths are now falling in America?

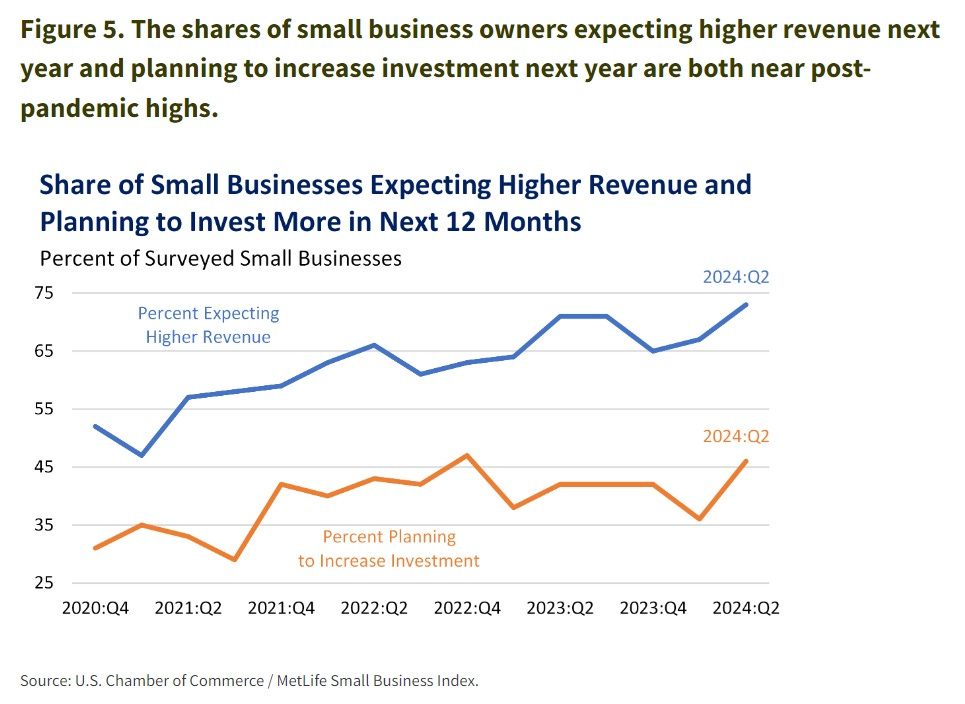

Did you know that small business is booming in America?

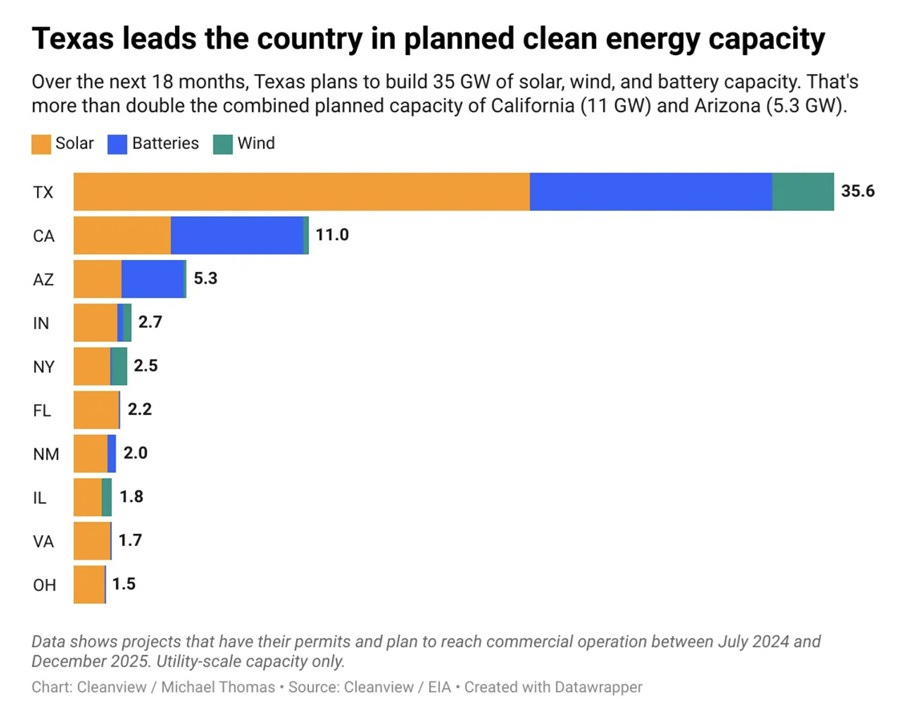

Did you know that Texas is building a huge amount of renewable energy?

Did you know groceries are now more affordable for ordinary American workers than in 2019?

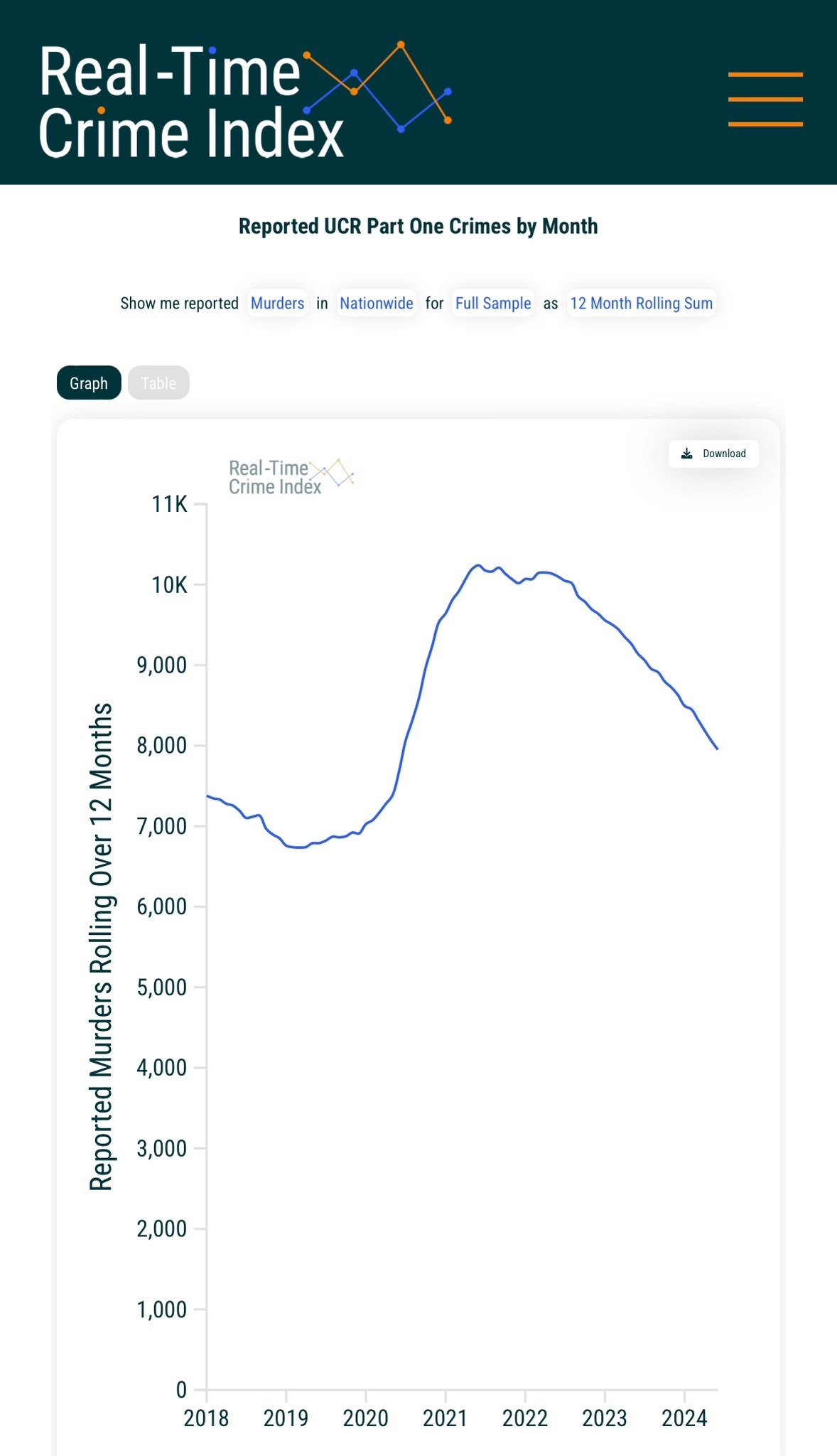

Did you know that plenty of independent data (not FBI data) confirms that crime is falling steadily in America?

It’s not all doom and gloom out there, folks.

Note that Studwell doesn’t claim land reform improves agricultural productivity, although some people confuse the two. Productivity takes costs into account, while yield is simply a measure of production per land area. Productivity is economic, yield is physical. Studwell argues that very small farms are inefficient from an economic standpoint, since they’re overly labor-intensive — in fact, he portrays this as a good thing, because it’s basically make-work for peasants.

I think Xi has a pretty simple strategy: Dominate every sector of manufacturing (the stuff economy), and steal/fast-follow the West across the information economy. This seems pretty smart!

China will always be able to do whatever information economy stuff the West pours its resources shortly after we do. Look at Ai, self-driving cars, etc. - the US is very slightly ahead, which is basically fine for China.

The West cannot do the same fast-follow to China's manufacturing. Manufacturing can't be stolen or copied. Ongoing unit costs matter much more than development costs. So China is pouring it's entire human capital base into the sector with the international moat.

I don't see how it's not the US that's lacking in strategy here.

I really object to your model of Xi as a conservative American baby boomer. It’s not as though there are no similarities—preoccupation with things that are coded as masculine, contempt for the kids, obsession with restoring his country’s greatness, preference for stability over dynamism, inflexible model of the world, etc.—it’s that Xi Jinping is a genuine Marxist-Leninist, a deep and committed Maoist, and all that entails.

American, conservative baby-boomers are not. On average, they are “get off my lawn!”, church-going, folk libertarians. Each are conservative, in the most basic sense (they want to conserve the institutions and practices of the country they were raised in) but because mid-20th century America and mid-20th century China were extraordinarily different places, the particular form of that conservatism is just so, so different.