At least five interesting things to start your week (#47)

Germany's mistakes; U.S. political parties; the VC winter; austerity; science and politics; TikTok propaganda; desalination

It can be challenging to write about my typical broad array of topics during an election season. We’re coming up around the bend here — just a little more than two more months of partisan shouting and talking points to go, and then we can get back to talking about the finer points of tax policy (which is, of course, what you all really want to read about). But there are still a bunch of interesting non-election-related things happening in the world, and that’s what quasi-weekly roundups are for.

Just one podcast today — an episode of Econ 102 with Erik Torenberg, where we talk about the presidential candidates’ policy positions:

See? There’s no escaping election stuff.

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things, only one of which is about the election. That’s not too bad, right?

1. Germany is still messing around with its future

About a year ago, I wrote a post arguing that Germany has become a country that is deeply unserious about its own future:

I argued that by allowing itself to become dependent on Russia and China, destroying its nuclear power plants, not spending enough on its military, and failing to address its chronic issues of NIMBYism and red tape, Germany was putting not only its own economy and physical security in danger, but that of all of Europe as well.

A year later, I fear that the situation I described has worsened on all fronts. The screenshot at the top of this post is from a video of Germany demolishing its nuclear plant at Grafenrheinfeld — a perfectly good zero-carbon energy source that had already been paid for and that didn’t make Germany dependent on Russia. Demolishing this nuclear plant and others like it was an extraordinary act of national stupidity. The result is that Germany is now going to spend a whole lot of money to build new carbon-emitting natural gas plants to replace the lost nuclear energy.

Germany is also notably failing to become Europe’s arsenal of democracy. Its defense budget increases have been far smaller than promised, despite the defense establishment’s warning that the country could soon be at war with Russia if Ukraine falls. And Germany is even putting a freeze on new military aid to Ukraine:

The German government will stop new military aid to Ukraine as part of the ruling coalition's plan to reduce spending…In a letter sent to the German defense ministry on Aug. 5, Finance Minister Christian Lindner said that future funding would no longer come from Germany's federal budget but from proceeds from frozen Russian assets…Berlin, which is Europe's main supplier of military aid to Kyiv, had already signaled a change in course on Ukraine last month, when the governing coalition of the Social Democrats, the Greens and the Liberals adopted a preliminary deal on a draft budget for 2025…to slash future assistance to Ukraine by half to €4 billion to fulfill other spending priorities.

Meanwhile, despite the existential threat to Germany’s auto and machinery industries, German companies continue to pour investment into China:

German direct investment into China has risen sharply this year, in a sign that companies in Europe’s largest economy are ignoring pleas from their government to diversify into other, less geopolitically risky markets…The investment, much of it driven by big German carmakers, comes despite warnings from Olaf Scholz’s government about the growing geopolitical risks associated with the Chinese market…

Experts say much of the investment dollars are reinvested profits earned in China…They said the uptick in German direct investment reflected a new “In China, for China” strategy pursued by companies such as Volkswagen aimed at shifting more production to one of their biggest markets.

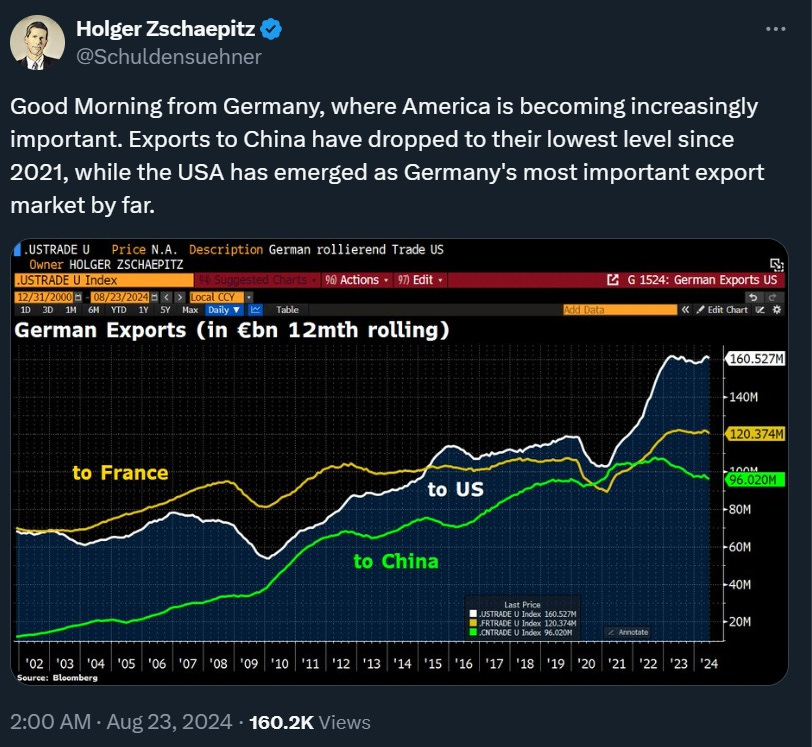

Shipping German industry overseas is causing a drop in Germany’s exports to China — one of the bright spots that saw Germany through the aftermath of the early 2010s crisis:

A partially-self-inflicted energy crisis and falling exports are among the reasons Germany’s economy is now the “sick man of Europe”:

And this is compounded by other long-term issues — a drop in the working-age population, a lack of public investment, and the aforementioned NIMBYism and red tape.

Overall, this paints a picture of a country whose leaders, elites, and voting public are deeply unserious. Instead of addressing the country’s myriad challenges, they are choosing to dither, bury their heads in the sand, indulge in comforting fantasies, and look out for themselves instead of for the national interest. As a result, things are getting worse, both for Germany and for Europe itself.

2. The Democrats are a strong party, the Republicans are a weak party

The Democratic National Convention demonstrated the party’s shift to a sunny, optimistic tone and its resurgent patriotism. But it also demonstrated something else that has become increasingly apparent over the last few years: The Democrats are a strong political party.

There were worries that the DNC would be disrupted by Palestine protesters, producing an embarrassing replay of 1968. In fact, nothing of the sort happened. Far fewer protesters showed up than predicted, forcing the protests to abandon mass demonstrations in favor of running around and annoying Democrats at lunch. A late push to force the Dems to let someone from the “Uncommitted Movement” speak at the convention failed. The protesters were left with nothing to do except issue histrionic rhetoric on social media:

Moreover, the Dems’ record fundraising numbers and swelling army of volunteers in the days since the start of the convention are proving they don’t need the allegiance of fringe activists like this.

The Democrats’ successful refusal to compromise or negotiate with fringe movements that refuse to endorse the Democratic nominee demonstrates that they’re a strong, centralized political party. But it isn’t the only such demonstration. There was also the rapid consolidation around Kamala Harris as the substitute for Joe Biden when the President dropped his reelection bid. Republicans howled that this was an undemocratic “coup” and that Democratic primary voters had been “disenfranchised”, but precisely no one other than GOP partisans seemed to care.

This is simply how strong political parties work. In 19th-century America, before the creation of primary elections, nominees were always chosen like this, in the proverbial “smoke-filled rooms”. Parliamentary democracies don’t even let people vote directly for the head of government — people choose the party, and the party chooses the country’s leader.

The advent of primaries weakened party bosses, but the Democrats were weakened less than the Republicans. After the disastrous nomination of McGovern in 1972, Democrats put in place the superdelegate system to make it harder for upstarts to force their nominee through at a divided convention. The Democrats also award their delegates proportionally in primary elections, meaning that an unpopular minority candidate can’t win the nomination by getting a plurality in a deeply divided field. (The Republicans, who award all of each state’s delegates to whoever gets a plurality, are still vulnerable to that sort of takeover — it was how Trump triumphed in 2016.)

The combination of superdelegates and proportional awards meant that Bernie Sanders had no chance in 2020 — but just to make sure the party rapidly coalesced around a non-Bernie nominee, Democratic party elders managed to persuade Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, and other moderate candidates to drop out and endorse Biden. This was another sign of a strong party.

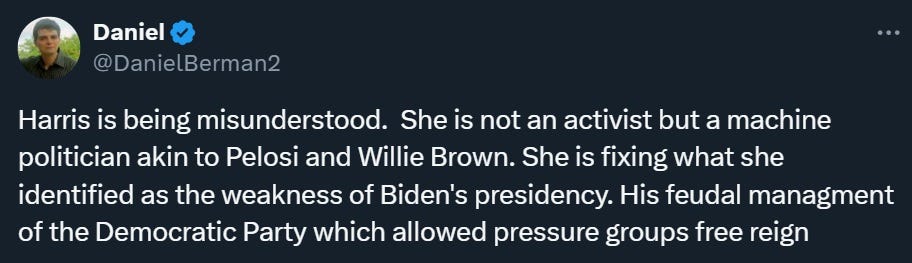

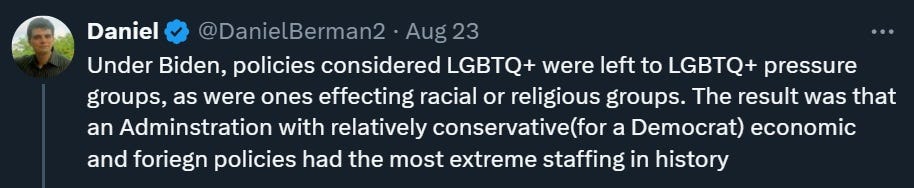

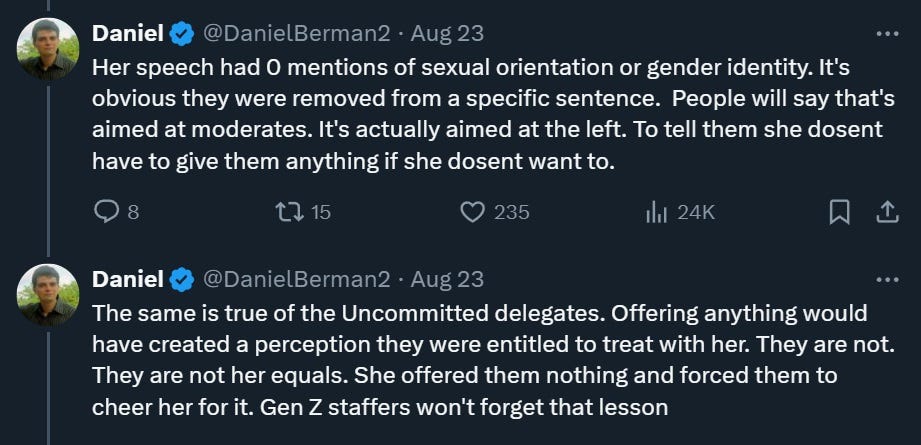

The main source of decentralization in the Democratic party is an array of special-interest pressure groups and activists. These are known in D.C. as “the Groups”. But speechwriter Daniel Berman has an interesting thread arguing that Harris intends to build up the party at the expense of the Groups. Some excerpts:

I can’t easily judge whether Berman’s theory is right. But it would certainly be in keeping with the general tendency toward organizational strength and centralization that we’ve seen from the Democrats since the divisive primary campaign of 2016 — and arguably since 1972.

And what about the GOP? As J.J. McCullough points out, all of the stars of this year’s GOP presidential effort — Trump himself, JD Vance, RFK Jr., Tulsi Gabbard, Vivek Ramaswamy, and Elon Musk — are party outsiders, and most of them were Democrats in the not-too-distant past. McCullough uses the term “hostile takeover” to describe what Trump and his retinue have done to the GOP, and it’s hard to disagree.

What happens to a political system with one strong party and one weak party? I don’t know, but that’s what we seem to have in America right now.

3. The quiet startup bust continues

Two weeks ago I wrote up some thoughts on the future of the tech industry. I argued that the successful build-out of the internet presented a challenge for venture capital and startups, as it meant that the model of low-cost high-upside investing that typified the internet years might now yield to more traditional types of opportunities. But when I podcasted about it with Erik Torenberg — who himself has been a VC — I was surprised to find that he was far more pessimistic than I was about the near future of that industry!

Shortly after that, via Josh Wolfe of Lux Capital, I saw some numbers that seem to bear out Erik’s pessimism:

Start-up failures in the US have jumped 60 per cent over the past year, as founders run out of cash raised during the technology boom of 2021-22…According to data from Carta, which provides services to private companies, start-up shutdowns are rising sharply, even as billions of dollars of venture capital gushes into artificial intelligence outfits…Carta said 254 of its venture-backed clients had gone bust in the first quarter of this year. The rate of bankruptcies today is more than seven times higher than when Carta began tracking failures in 2019…

…Even for strong companies, public listings have dried up and M&A activity has slowed. That has prevented VCs from returning capital to the institutional investors who back them — an essential precursor to future fundraising.

Only 9 per cent of venture funds raised in 2021 have returned any capital to their ultimate investors, according to Carta. By comparison, a quarter of 2017 funds had returned capital by the same stage.

In 2022 it was possible to blame macro factors for this bust. Friends in the industry talked to me about the broader stock market crash, which drove down the price of “comps” — big companies that represented the success case for startups. But stocks went back up; the NASDAQ is now past its late 2021 peak, and the broader market is up by even more. The U.S. economy has been doing great, with strong growth, rapid productivity growth, and surging consumption. But the startup sector didn’t recover.

In fact, the bust doesn’t seem to be related to the supply of funding at all. Sure, interest rates are still high, but VCs already raised a lot of money back in the boom that they could be deploying now, but aren’t (known as “dry powder”). The problem is that demand for funding is limited — there just aren’t as many promising startups now, and many of the ones VCs thought were promising turned out not to be so great after all.

Thus, what VC money is being deployed is being increasingly plowed into AI. But if AI startups don’t end up making money the same way internet startups did, the VC bust will be even bigger than it has been so far. We could be looking at a “VC winter”.

4. Preparing for the Age of Austerity

I’ve been arguing for a while that no matter which party triumphs in this year’s election, pressures for fiscal austerity are going to increase. This is not a thing that progressives want to hear — heck, it’s not a thing conservatives want to hear either. Over the long years of low interest rates, both parties got used to the idea that deficits didn’t matter. Well, now they do, thanks to higher interest rates, slow population growth, and the overhang of debt from multiple crises and multiple periods of fiscal irresponsibility.

One pundit who has been banging this drum even louder than I have is Vox’s Dylan Matthews. In a must-read post entitled “The US government has to start paying for things again”, he lays out his case:

Coming of age as an economics reporter in the 2010s…Younger folks like me distinguished themselves by embracing deficits…It was madness to worry about cutting the deficit when more spending or tax cuts or both could achieve the much more important goal of helping people get back to work [during the Great Recession]. And it was especially stupid when interest rates on the debt were at record lows…

But the 2024 economy is not the 2011 economy. Interest rates are much higher. Unemployment is at 4 percent…Wages are rising…And the national debt is climbing higher and higher…

There’s no magic number at which the debt load becomes a full-on crisis. But it steadily becomes a bigger and bigger problem, and the trajectory we’re on is worrisome. It’s especially worth taking debt more seriously when other problems that deficit spending can help solve, like mass unemployment, have been fixed. Moreover, without tackling the debt problem, tackling other problems, from child poverty to housing costs to climate change, will become harder as the government has less space to spend and invest.

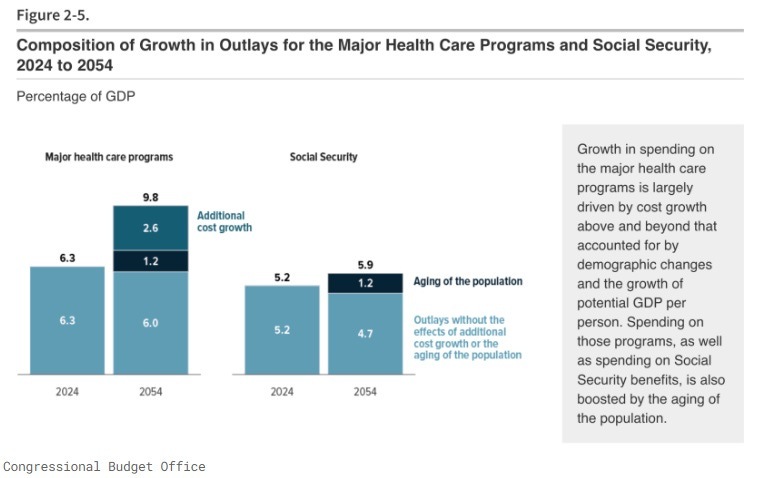

Debt is a problem right now, due to rising interest costs. But it’ll be even more of a problem in the future. Matthews singles out Social Security and (especially) Medicare, Medicaid, and other government health programs as the primary culprits of this future increase:

As you can see, a little less than half of the problem is due to population aging. Not much can be done about that — immigration can help, but only a little bit, since most immigrants are already partway to retirement when they arrive. But a bit more than half of the problem is projected health care cost growth. Health care costs are eating the nation.

Matthews has five suggestions for what to do about the debt:

First: use tax hikes or spending cuts to offset any new spending or tax cuts…

Second, take growth seriously…expanded green cards for immigrants with science and engineering degrees seems like a no-brainer…funding for scientific research boosts productivity…

Third: the coming tax fight in 2025 should be used to raise revenue, not just avoid losing it…Taking the debt at all seriously means that whoever’s in office next year needs to pay for whatever part of the Trump cuts they want to keep…

Fourth: Social Security should be addressed, not punted…Democrats will push to pay for the program by raising taxes on high earners; Republicans will push for benefit cuts. Either way, the gap needs to be filled…

Fifth and finally, Congress needs to work to ensure that per-person health spending stays roughly constant.

These are all good suggestions, but Matthews doesn’t touch the third rail here: spending less government money on health care. Prices are partly a function of demand, and when you stop shoveling more and more money into a service industry, prices tend to go down. This is why the cost of college is finally decreasing — colleges didn’t become more efficient, they were simply unable to keep charging sky-high prices in the face of shrinking demand.

This can work for health care too. Medicare and other government health programs can more aggressively negotiate prices, as they’ve begun to do recently with pharmaceuticals. But the government can also choose to spend less on health care, both by cutting benefits for these programs and also by reducing the tax exclusion for employer-provided health insurance. Doing that wouldn’t just save the government money directly — it would save it money indirectly as well, by causing health care costs to fall.

This is the third rail of American politics for multiple reasons. First, nobody wants their health benefits cut. Second, the 11% of Americans who work in the health care industry certainly don’t want to see rounds of layoffs and wage cuts. But what’s the alternative? America’s health care costs twice as much as other rich countries’, relative to GDP, despite achieving similar results. Everyone wants to keep shoveling money into this system, but at some point it’s got to stop. I have no idea who can stop it, though.

5. Science and politics don’t mix

One topic I write about periodically is the intersection of science and politics:

Basically, my position is that although it’s never possible to make science totally apolitical or to expunge ideological bias from science completely, scientists should do both of these things as much as possible. Not only does politicized science reduce society’s trust in the enterprise of science in general, but it also encourages researchers to embrace shoddy theories, poor analysis, and fraudulent data.

Now Alabrese, Capozza, and Garg have a paper showing that the first of these costs — reduced trust in science — is very real. They showed scientists’ tweets to regular folks, and then measured how much the subjects trusted the scientists’ research. They found that when scientists tweet highly politicized things, it reduces laypeople’s trust in their research:

We find that 44% of a sample of 97,737 U.S. academics on Twitter have expressed political opinions — they have made at least one non-neutral post on any of our salient topics in the period from 2016 to 2022 — compared to 7% of the general non-academic Twitter user base. We document significant ideological polarization among academics on five politically salient topics…

To study the implications of scientists’ online political engagement on public perception, we conducted an online experiment…This experiment assessed the impact of online…political expression by presenting a representative sample of 1,700 U.S. respondents with vignettes featuring synthetic academic profiles varying the scientists’ political affiliations based on real tweets. Our findings reveal a significant ’credibility penalty’ for scientists engaging in political discourse. Scientists on both the ’left’ and ’right’ of the political spectrum experience a…penalty when displaying a political affiliation. This penalty manifests as reduced public perception of credibility for both the scientists and their work, as well as decreased public willingness to engage with scientific content…

[O]ur study shows that political expression by scientists impacts both their personal and perceived scientific credibility. In an era of declining trust in scientific expertise, understanding factors shaping public perceptions of scientists’ credibility is vital. Our findings call for reassessing science communication strategies to maintain credibility[.]

This result isn’t surprising to me, and it probably isn’t surprising to scientists either. The authors interview some scientists who post on Twitter and find that they know their credibility will take a hit from their posts. But they think the impact of their public political expression is so important that they go ahead and do it anyway.

My intuition says that scientists are vastly overestimating their own impact on the political process. Just because people trust scientists to tell them facts about biology or physics doesn’t mean they care about scientists’ opinions on racism or immigration or democracy any more than the opinion of the average citizen. Scientists probably get political because they perceive that they’ll be treated as experts on political issues — but they won’t. Which means the cost-benefit calculation of being a Twitter activist is usually much more unfavorable than scientists think.

6. TikTok is still suppressing speech

24 roundups ago, I noted some very solid evidence that TikTok was suppressing speech critical of the People’s Republic of China:

A new study by the Network Contagion Research Institute confirms that [China’s use of TikTok for propaganda purposes] is already happening, in a very substantial way. By comparing the hashtags of short videos on Instagram and TikTok, they can get an idea of which topics the TikTok algorithm is encouraging or suppressing…Hashtags dealing with general political topics (BLM, Trump, abortion, etc.) are about 38% as popular on TikTok as on Instagram. But hashtags on topics sensitive to the CCP — the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Hong Kong protests and crackdown, etc. — are only 1% as prevalent on Tiktok as on Instagram. The difference is absolutely staggering…[O]verall, the pattern is unmistakable — every single topic that the CCP doesn’t want people to talk about is getting suppressed on TikTok.

Now the NCRI has come up with another study that complements their earlier one with a different methodology, but finds exactly the same thing:

Videos condemning or negatively depicting China’s human rights abuses are more difficult to find on TikTok than other rival networks, a new study finds…US TikTok users who search for terms like “Tiananmen,” “Tibet,” and “Uyghur” — words commonly used in Chinese Communist Party propaganda — see less “anti-China” content than those same searches produce on Instagram and YouTube, according to a new study from the Network Contagion Research Institute at Rutgers University.

Analysts created 24 new accounts across ByteDance Ltd.-owned TikTok, Meta Platforms Inc.’s Instagram and Alphabet Inc.’s YouTube, to replicate the experience of American teenagers signing up for social media. When searching for keywords often related to the country’s human rights abuses, TikTok’s algorithm displayed a higher percentage of positive, neutral or irrelevant content than both Instagram and YouTube, the study found.

TikTok angrily denied that the evidence indicates Chinese government manipulation of the algorithm, but their denials were vague and short on explanations. Between this study and the previous one, it’s clear that someone in China is controlling the TikTok algorithm to censor Americans’ criticism of the CCP.

It is unclear to me how foreign government censorship of a U.S. social media platform constitutes “free speech”.

7. Energy abundance is water abundance

I write a lot about how green energy is also cheap energy. Solar power and batteries won’t just allow us to sustain industrial civilization without cooking the planet — they’ll also give us the first fundamental improvement in energy technology since the oil age began, and hopefully get energy usage per capita growing again after its long stagnation. Energy won’t actually get “too cheap to meter” — demand will grow as people find new uses for energy. But it’ll become more abundant.

But who cares? Why do we need more energy? People in rich countries can already afford to light their houses, drive to work, power their computers, run their refrigerators, etc. Why do we need energy to be even cheaper, except maybe to throw more electricity at AI and Bitcoin mining?

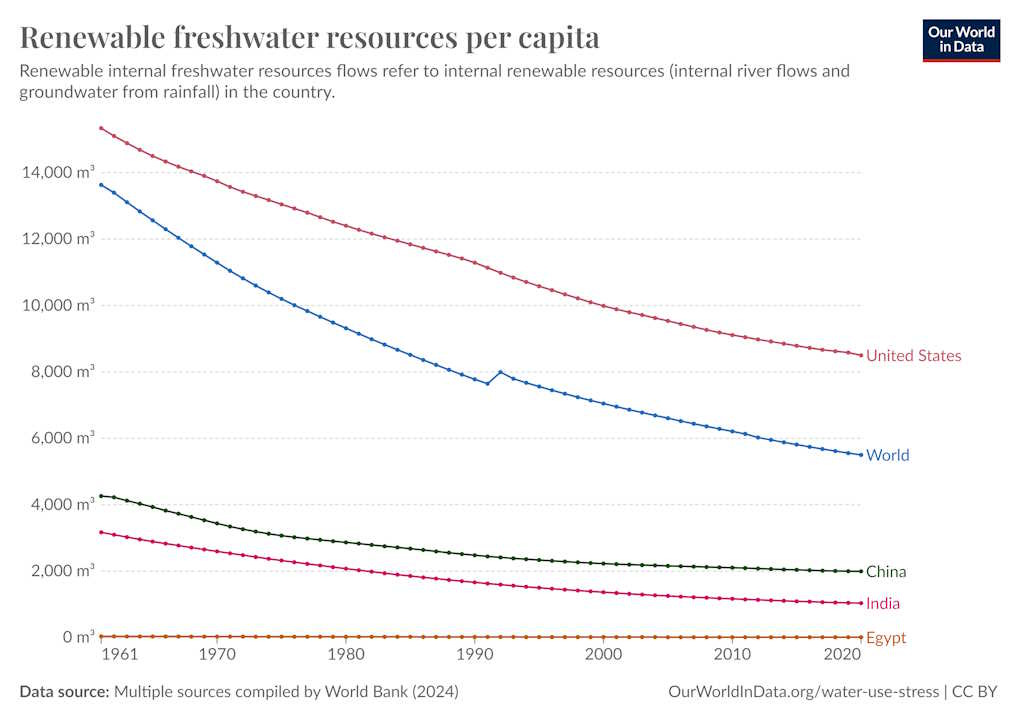

One important answer is desalination. Currently, we live in a water-constrained world — water scarcity raises the price of food, as well as all kinds of other stuff. America is pretty water-rich, but that’s not true for a lot of other countries, including the ones where the most people live:

Fresh water is a limited resource — we can’t easily conjure more of it up at will.

Well, that is, we couldn’t, until now. Thanks to cheap solar energy, desalination is about to get much cheaper on a mass scale. When that happens, many of the water constraints that now define our world could suddenly be relaxed, opening up vast realms of human possibility. An excellent article by Anna-Sofia Lesiv from 2023 explains how desalination works, why it’s important, and how we might use it to alleviate water scarcity in dry regions like the Middle East. Other writers are even more ambitious, suggesting filling up new bodies of fresh water, declaring that drought is now optional, or suggesting the reforestation of large parts of the Earth.

This won’t just give us cheap food and more powerful showers and dishwashers. It’ll fundamentally transform the economic geography of the whole planet. The Middle East, North Africa, and other very dry regions will suddenly become much more livable (climate change willing, of course). That will affect the economic balance of power in the world, reduce migration pressures, and raise living standards for a huge swath of humanity.

Energy abundance is water abundance, and it’s on the way.

Sounds like Dems are finally listening to Abigail Spanberger (D-VA) who said, in 2018, "We will get fucking torn apart” if this crazy leftism continues.

I'm reading still, the Kenneth J Arrow paper you provided of December 1963. Fundamentally, it seems like a good argument forba single payer, price negotiating, National Healthcare system. Ah! Medicare and then Medicare for all.

Secondly. My family had free Healthcare in 1963. Free maternity care. Free hospitalizion. Miniscule family physician costs. Why? Because most of American Healthcare was provided by Charity hospitals, non profits. City Hospital, County Hospital, Catholic, Presbyterian, Jewish, University Hospitals. All free.

A. Blow up and destroy the non value add Health insurance industry. Proves zero value.

B. Medicare For All

C. Everyone pays

D. All hospitals back to non profits or state, city and county governments.

E. Cap medical doctor salaries and clinics incomes.

F. Put Pharmaceuticals on a Defense Department FAR bid basis like Cost plus and Firm Fixed Price.

G. Social Security. Easy. Tax the untaxed economy. OASDI receipts as percent of GDP fell from about 8-9% to 4% apx. 5% of GDP is $1 Trillion of missing Social Security receipts. Why? W-2s have fallen as percent of GDP as non wage income in PE, IB, Capital gains, large untaxed wealth transfers of Estates, trusts, real estate are not, but all should be, FICA taxed