At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#44)

Poland vs. China; smartphones; basic income; the soft landing; wages and automation; software and inequality; immigrant doctors

I’m sick right now, which you’d think would reduce my productivity, but really what it means is that I have nothing to do besides sit at home and write. That’s why yesterday I was able to pump out a 5000-word post in five hours. Fun! Anyway, now I’m catching up on all the econ stuff I wanted to write about, but which I’d been neglecting due to all the political news over the last two weeks.

But first, podcasts. I have two episodes of Econ 102 for you this week, both of which talk about Donald Trump:

Anyway, enough of Trump. On to economics!

1. Which has grown faster, Poland or China?

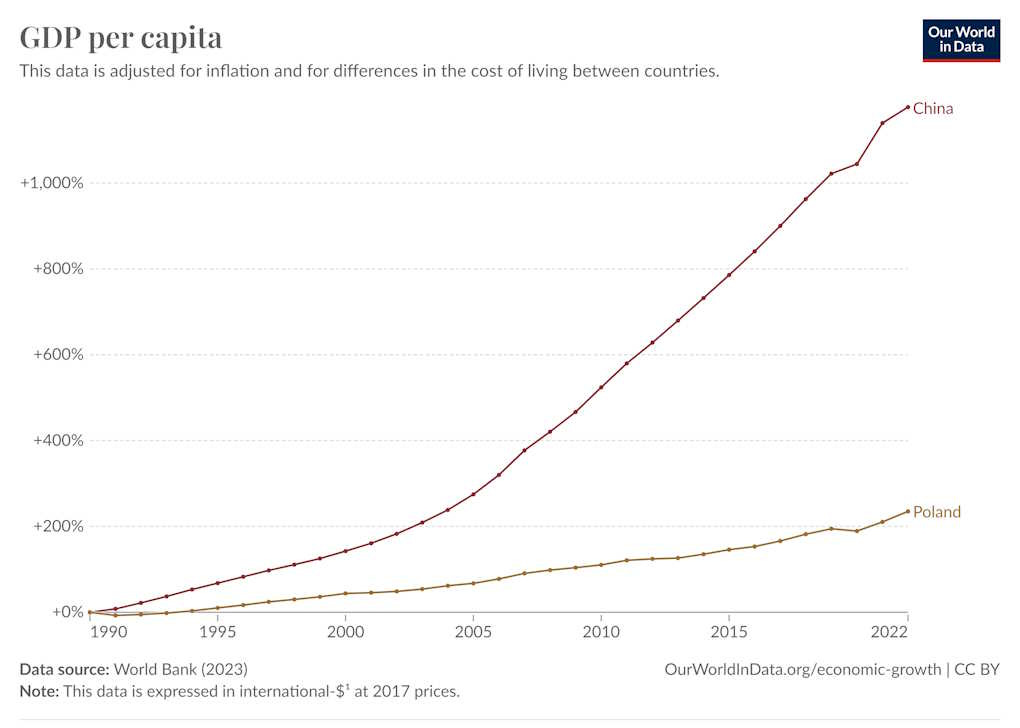

On the face of it, this may seem like a silly question. Poland is great, but everyone knows China is the world’s growth champion…right? Just look at a comparison of how far each one has come since 1990:

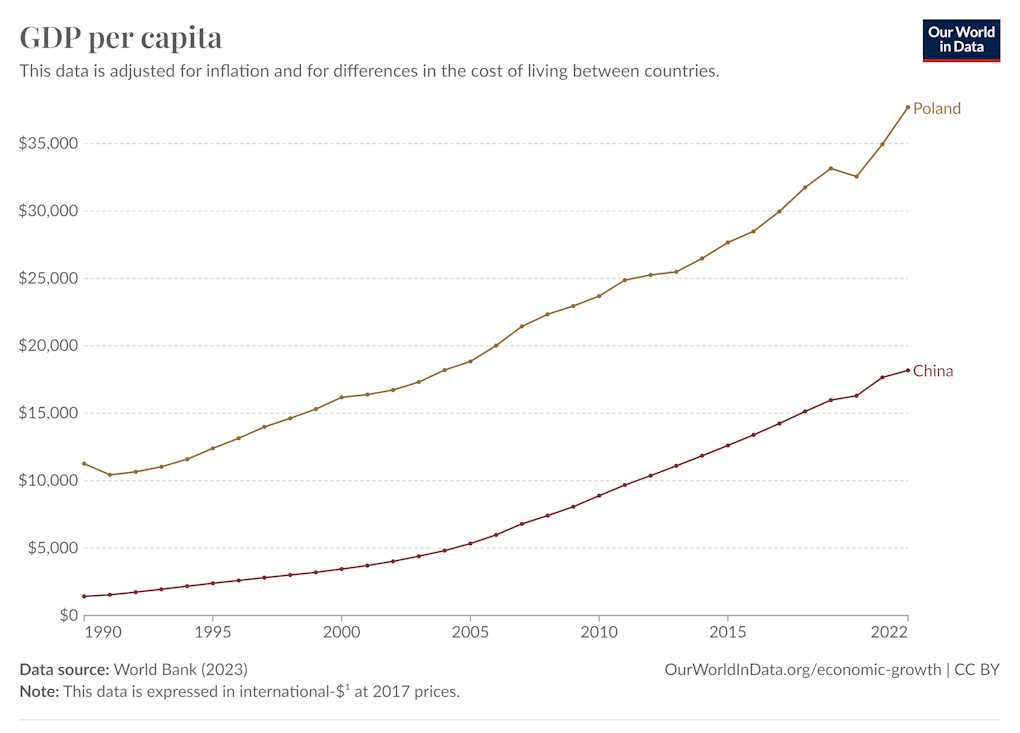

But the thing is, China’s hypergrowth started from a very, very low base — much lower than Poland’s. When we look at the actual number of dollars that each country added to its GDP over the past few decades, Poland actually comes out comfortably ahead. In fact, Poland has been slowly but steadily been increasing the difference in GDP between itself and China:

Should we think about growth in exponential or linear terms? Usually, we define growth as a percentage rate — we think of it as an exponential. But just because you can calculate the percentage growth rate of something doesn’t mean that it has an exponential functional form! In fact, there’s some evidence that as countries become rich, growth goes from exponential to linear.

But anyway, to do a real apples-to-apples comparison, we need to compare the countries’ growth rates at similar levels of income. One fundamental fact of development economics is that poor countries have much higher potential growth than rich ones. “Potential” doesn’t mean “actual” — poor countries don’t always grow fast, and many remain mired in poverty. But if you’re a poor country, you can A) absorb a lot of foreign technology without having to invent it yourself, and B) save and invest a lot to increase your capital stock. That means it’s easier to grow fast from a low base.

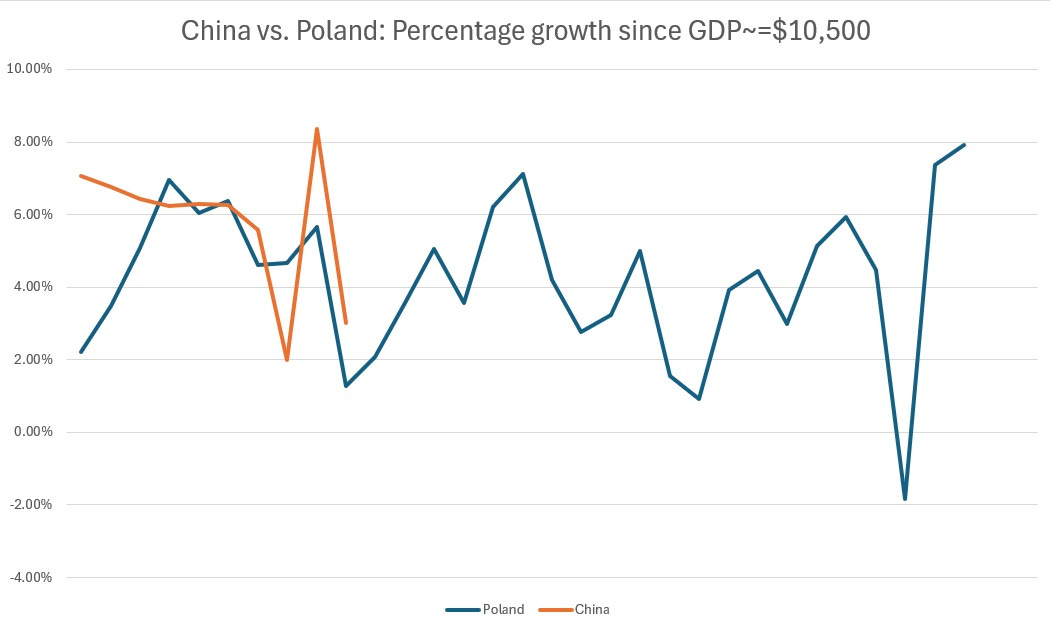

In 1991, Poland’s GDP per capita (PPP) was about the same as China’s in 2012 — somewhere around $10,500. So we can look at percentage growth rates in the years since hitting that level:

The growth rates over the decade since ~$10,500 look roughly comparable (and keep in mind that China has probably overstated its growth since the pandemic, and possibly earlier as well). What’s interesting is that in recent years, China’s percentage growth has steadily slowed down, while Poland’s has held constant or actually accelerated. In fact, if we project the trend lines since ~$10,500, Poland comes out looking a little better, due to its recent reacceleration and China’s recent deceleration.

Let’s not minimize the awesomeness of China’s accomplishments here, of course. China’s climb out of poverty under Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao was truly spectacular. But climbing out of poverty is not the same thing as becoming a rich country. And it’s here that Poland has already succeeded, while China has yet to prove itself.

2. It’s probably the phones

I’m generally a rabid techno-optimist, but when it comes to smartphone technology, I can be a bit of a pessimist. I just don’t think humans have learned how to handle smartphone technology yet. The combination of smartphones and social media is the most plausible explanation for why kids all over the world suddenly became far less happy in recent years:

Over the last year, Zach (Rausch) has written a series of articles examining the international scope of the youth mental health crisis. In his five-part series, he has shown that measures of anxiety, depression, and other measures of poor mental health among youth have worsened in the five Anglo nations, the five Nordic nations, and many other nations throughout Western and Eastern Europe. Zach has also shown that suicide rates are up for Gen Z girls across the Anglosphere, with higher rates than any generation of girls that came before them.1 He also found the same trends for emergency department visits and hospitalizations for non-fatal self-harm. In addition, Zach has documented variations in suicide and self-harm across Europe, showing that social, cultural, and religious factors have a mitigating effect on such behaviors…

There is a literature of at least 600 published papers suggesting that happiness is U-shaped in age…In other words, when a person is young, they are as happy as they are going to be until old age…The U-shape has been apparent across a whole range of well-being metrics, including life satisfaction, financial satisfaction, worthwhileness, and happiness. Every U.S. state had a U-shape…But not anymore. It seems that the well-being of young adults (ages 18-25), especially young women, went into precipitous decline beginning around 2017…

The hump shapes and U-shapes in age have disappeared into the ether. Now, young adults (on average) are the least happy people. Unhappiness now declines with age, and happiness now rises with age—and this change seems to have started around 2017. The prime-age are happier than the young. The evidence for this transformation first became apparent in the United States and the United Kingdom, but it is now true in 82 countries worldwide.

When you see an international trend like this, chances are that it’s neither cultural nor political in origin. It’s most likely technological. And smartphones plus social media are the most important technology that has changed teenagers’ lives around the world over the past decade.

Of course, it would be nice to have evidence of actual causation here, not just correlation. In fact, that evidence is starting to emerge. A recently published RCT by Schmidt-Persson et al. in Denmark found that having both young people and adults exchange their smartphones for flip phones resulted in major improvements in their reported well-being, a decrease in reports of negative emotions and difficulties with their peers, an increase in prosocial behavior, fewer behavioral issues for kids, and even more exercise.

Obviously we need to wait for a lot more such RCTs to come out before we draw firm conclusions. But we should consider the strong possibility that the way our society uses smartphones needs to be significantly changed.

3. More disappointing results for basic income

Three weeks ago, I flagged some mildly disappointing results from a basic income project in Denver. Now we have the results of a far bigger and longer randomized controlled trial of basic income in northern Illinois and central Texas, and the results are even more disappointing. This is from a paper by Vivalt et al. summarizing the main results:

We study the causal impacts of income on a rich array of employment outcomes, leveraging an experiment in which 1,000 low-income individuals were randomized into receiving $1,000 per month unconditionally for three years, with a control group of 2,000 participants receiving $50/month. We gather detailed survey data, administrative records, and data from a custom mobile phone app. The transfer caused total individual income to fall by about $1,500/year relative to the control group, excluding the transfers. The program resulted in a 2.0 percentage point decrease in labor market participation for participants and a 1.3-1.4 hour per week reduction in labor hours, with participants’ partners reducing their hours worked by a comparable amount. The transfer generated the largest increases in time spent on leisure, as well as smaller increases in time spent in other activities such as transportation and finances. Despite asking detailed questions about amenities, we find no impact on quality of employment, and our confidence intervals can rule out even small improvements. We observe no significant effects on investments in human capital, though younger participants may pursue more formal education. Overall, our results suggest a moderate labor supply effect that does not appear offset by other productive activities.

Just $1000 a month made 2% of people stop working! That’s a very large negative effect. It contradicts the results of earlier studies showing little or no effect of unconditional cash benefits on employment. And worst of all, the basic income recipients didn’t seem to transfer to better jobs or go back to school — two of the most powerful arguments for basic income. Instead, people just sat around at home.

Now, increased leisure time isn’t zero benefit — obviously it’s nice to be able to sit around and do nothing and live off of government cash for a little while. But it represents a steep tradeoff — programs like this are already very expensive in fiscal terms, and if they make people work less, that only adds to the total economic cost. If leisure time is all we’re getting for all of that money and lost output, it’s highly questionable whether the intervention is worth it.

That doesn’t mean cash benefits are useless. First of all, this is just one study, even if it is the best study we have so far. A number of earlier, smaller trials showed no effect. And second, unconditional cash benefits may be a better form of redistribution than more traditional welfare programs with complicated work requirements, confusing qualifications and application procedures, etc. But if it’s confirmed that basic income discourages work and provides little long-term career benefits, I think interest in the idea will wane rapidly.

4. Another explanation for the soft landing

The question of how America managed to bring down inflation without hurting the real economy is quite possibly the most interesting macroeconomic question right now. Usually, raising interest rates will bring down inflation, but only at the cost of hurting the real economy and raising unemployment. The fact that the U.S. got away with bringing down inflation without hurting the economy implies that either A) there was a big shift in inflation expectations that became a self-fulfilling prophecy, or B) there was some sort of positive supply shock going on. The most common hypotheses for positive supply shocks are the drop in energy prices and the end of Covid-era supply chain problems.

But Stephen J. Davis has a working paper offering an alternate explanation. He cites 1) the end of pandemic social distancing, and 2) the rise of remote work as positive supply shocks. Davis argues that both of these things raised labor supply, pushing down costs and prices while supercharging growth:

Two extraordinary U.S. labor market developments facilitated the sharp disinflation in 2022-23 without raising the unemployment rate. First, pandemic-driven infection worries and social distancing intentions caused a sizable drag on labor force participation that began to reverse in the first quarter of 2022, and perhaps earlier. As the reversal unfolded, it raised labor supply and reduced wage growth. Second, the pandemic-instigated shift to work from home (WFH) raised the amenity value of employment in many jobs and for many workers. This development lowered wage-growth pressures along the transition path to a new equilibrium with pay packages that recognized higher remote work levels and their benefits to workers.

This sounds plausible. But the end of social distancing can’t easily explain the divergence between the U.S. and other rich countries. If Davis’ story is right, it means that America’s more rapid embrace of remote work would explain the difference.

Anyway, Davis’ ideas deserve to be added to the pile of potential explanations for the soft landing.

5. High wages spur faster automation

Back in the 2010s, a lot of people debated something called “Verdoorn’s Law”. This is the observation that productivity tends to grow faster during economic expansions than in downturns. One explanation for this correlation — commonly known as “Real Business Cycle” theory — says that the productivity increases drive the economic expansions. An alternative theory says that when demand is high and labor markets are tight, companies invest more in new technology.

Now Mick Dueholm, Aakash Kalyani, and Serdar Ozkan have a bit of evidence for the latter theory:

[T]he tight labor market in the years following the COVID-19 recession might have prompted firms to increase their investment and automate some tasks…We found that a 1-unit increase in a firm’s labor issues leads to a 28 basis point increase in its investment. To put this investment effect into perspective, our estimate implies that since 2021, the increase in labor issues (due to, for example, tighter labor markets) has spurred approximately an additional $55 billion in investment in the U.S. economy…This is…similar in size to funding appropriated through the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act…

[F]irms that discuss labor issues are 45% more likely to talk about automation in earnings calls compared with the average firm…[A] 1-unit increase in labor issues is associated with an 8.9 basis point increase in productivity growth after four quarters.

This implies that running the economy hot isn’t just good for wages and employment — it’s also good for productivity growth. Something to think about.

It should also make us think hard about unions, minimum wage laws, sectoral bargaining, and other policies to force up wages. If forcing wages higher leads to greater investment in new technology, and if investment in new technology creates an externality that leads to more advances in technology, then forcing wages higher via unions and government policy might be economically efficient. After all, this is one of the leading theories for how the Industrial Revolution got started.

6. Some evidence for the “software increases inequality” thesis

One thing that annoyed me about the book Power and Progress was the way it told just-so stories about economic history. The information technologies of the past — telegrams, telephones, etc. — are assumed to have been job-creating, while the information technologies of recent decades — software and the internet — are assumed to have been job-destroying. This is despite the fact that one of the authors, Daron Acemoglu, found no correlation between IT investment and employment in his 2017 paper with Pascual Restrepo.

But an interesting new paper by Sangmin Aum and Yongseok Shik finds evidence that software investment replaces labor, increasing corporate profits while holding down wages:

Using firm- and establishment-level data from Korea, we divide capital into equipment and software, as they may interact with labor in different ways. Our estimation shows that equipment and labor are complements…consistent with other micro-level estimates, but software and labor are substitutes…a novel finding…As the quality of software improves, labor shares fall within firms because of factor substitution and endogenously rising markups. In addition, production reallocates toward firms that use software more intensively, as they become effectively more productive. Because in the data these firms have higher markups and lower labor shares, the reallocation further raises the aggregate markup and reduces the aggregate labor share. The rise of software accounts for two-thirds of the labor share decline in Korea between 1990 and 2018. The factor substitution and the markup channels are equally important.

This is a very interesting finding, although it needs replication — especially in light of other papers like Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017) that find no correlation here. It needs to be replicated. But if it holds up, it means that software works differently than other technologies. The question would then be why it works differently, and whether this is true for all kinds of software and for all kinds of companies.

But it’s possible that the shift of technology from “atoms” to “bits” really was a driver of increased inequality and the fall in the labor share. If so, it implies that rapid innovation new physical technologies — solar, batteries, new materials, and so on — could help reignite a type of growth that’s healthier for workers and for society as a whole.

7. How to get more doctors in America

In an age when immigration has become a culture-war wedge issue that divides right and left, it’s great to hear of a case where conservatives encouraged more immigration. A number of states — most of them “red states” run by Republicans — are making it a lot easier for immigrant doctors to work in the U.S.:

America’s physician shortage is nothing to sneeze at. For primary care alone, the country will be short more than 40,000 doctors by 2030…There is a solution. States are starting to see the value of letting internationally licensed physicians help fill their doctor shortages. Govs. Kim Reynolds and Glenn Youngkin signed bills recently allowing Iowa and Virginia to join Tennessee, Florida, Wisconsin and Idaho to create a pathway for doctors practicing abroad to become fully licensed without completing unnecessary post-medical-school “residency” training in the U.S.

Previously, doctors licensed outside the U.S. had to come as trainees, or “medical residents,” even if the training was repetitive. This meant top foreign doctors who treat professional athletes around the world, for example, could treat American athletes only overseas. Or doctors who wanted to help underserved communities in the U.S. would have to take lower pay and repeat training they had already completed in another country…

These bills have earned bipartisan support…On Jan. 1, Tennessee stood alone as the only state allowing internationally licensed doctors to become fully licensed. By year’s end, we may see more than 10 states with a legislative or administrative pathway on the books.

This is great news — not just because it’ll help solve the doctor shortage, remove burdensome regulation, and improve economic efficiency, but because it’s a very clear and obvious demonstration of how immigration directly benefits Americans of all political persuasions and from all walks of life. More of this, please.

w.r.t. physician shortage, I keep repeating myself but US needs to follow the MBBS model that many countries follow. There's absolutely no reason why the rest of the world allows students to get into med school right after high school and finish in 5 years vs the US system of 4 years of undergrad/pre-med + 4 years of med school. It severely limits the pool of students who want to become a doctor when you can join a FAANG company right after undergrad (or in some cases, after high school). 3 - 4 years of extra school is a big deal and it's not like American doctors are better than doctors elsewhere.

I have the opposite framing of the basic income study. People were given an income equal to that of a full time minimum wage job, and 98 per cent of them kept working.