Anti-anti-neoliberalism is also not enough

We're never going back to the 1990s, and the Biden years have important things to teach us.

Right now Democrats are wandering in the wilderness in the wake of their 2024 electoral defeat, looking for some sort of message or mission to rally the voters around. A lot of that message is probably going to involve a backlash against Trumpian chaos, the excesses of DOGE, and whatever mistakes Trump makes between now and the midterm elections. Some of it will be social stuff like abortion rights. But economic policy is inevitably going to have to be part of the Democrats’ message. And so there’s an internal intellectual battle being waged on the left right now, about what the Democratic economic program should be.

Since the financial crisis of 2008, and especially since Hillary Clinton’s loss in 2016, support has been building for a new progressive economics. The thinkers behind this program were people like Joseph Stiglitz, James K. Galbraith, Elizabeth Warren, and Robert Reich. The work was carried forward and fleshed out by a bunch of progressive think tanks and foundations, including the Roosevelt Institute, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, the Hewlett Foundation, and Employ America.

Different people within the movement emphasize different ideas, and there are certainly internal disagreements, but the new progressive economics is basically:

Subsidies for “care industries” like health care, eldercare, and child care

Vigorous antitrust and suspicion of corporate concentration

Strong support for unions, and for policies to push up wages.

Industrial policy, especially for green technologies to fight climate change

An expanded welfare state focused on child tax credits

Higher taxes on the super-rich

A general suspicion of fiscal austerity, tolerance of government deficits, and a focus on full employment above all other macroeconomic goals

This new progressive economics found its champion in the Biden administration, who enacted or tried to enact most of its precepts. Biden dished out large health care and child care subsidies, expanded the child tax credit enormously (though temporarily), strengthened antitrust, ran big deficits, created green industrial policy, and was probably the most pro-union President in history.

I think there are a lot of problems with this new progressive economic paradigm, and I’ve spent a fair amount of time criticizing its weaknesses. Here are three posts I wrote on the topic:

Politically, the program just wasn’t popular enough to win the hearts and minds of Americans, who generally disapproved of Biden on the economy and trusted Trump more than Harris. But there were plenty of issues with the substance, too. Subsidies for care jobs pushed up prices in these already-overpriced service industries. Progressives’ dogmatic adherence to proceduralism and vetocracy stymied many of their flagship programs, from California’s high speed rail line to rural broadband to EV charging stations. Meanwhile, the relentless focus on job provision and full employment would have worked a decade earlier during the Great Recession, but it backfired badly in the inflationary macroeconomic environment of the post-pandemic period, and ended up exacerbating inflation.

So the new progressive economics needs to be taken back to the workshop and given some extensive modifications, to say the least. But that doesn’t mean the Democrats should — or will — swing back to “neoliberalism”, the more market-friendly approach that prevailed during the Clinton and Obama presidencies. Neoliberal Democrats who hope that Trump’s tariffs and Harris’ defeat will lead to a reversion to the old orthodoxy are going to be disappointed. There were important reasons that both parties moved away from neoliberal approaches, and those reasons haven’t gone away.

For example, Jason Furman, one of Obama’s top economic advisors, recently published an article in Foreign Affairs called “The Post-Neoliberal Delusion” that denounces Biden’s economic record:

Since the 1990s, Democratic economic policy had largely been shaped by a technocratic approach, derided by its critics as “neoliberalism,” that included respect for markets, enthusiasm for trade liberalization and expanded social welfare protections, and an aversion to industrial policy. By contrast, the Biden team expressed much more ambition: to spend more, to do more to reshape particular industries, and to rely less on market mechanisms to deal with problems such as climate change. Thus, the administration set out to bring back vigorous government involvement across the economy, including in such areas as public investment, antitrust enforcement, and worker protections; revive large-scale industrial policy; and support enormous injections of direct economic stimulus, even if it entailed unprecedented deficits.

Some of Furman’s critiques in this piece ring true. But although he is a brilliant and perceptive guy — regular Noahpinion readers know that I cite him all the time — Furman overstates his case pretty significantly here.

For example, here is Furman’s overview of Biden’s economic record:

In some respects, the macroeconomic outcomes have been impressive. The U.S. economy has bounced back much faster than it did after previous recessions, and its post-pandemic performance has also outpaced that of many peer countries in terms of economic growth. But the recovery has been uneven, frustrated by inflation at least partly induced by the administration’s own policies. Inflation, unemployment, interest rates, and government debt were all higher in 2024 than they were in 2019. From 2019 to 2023, inflation-adjusted household income fell, and the poverty rate rose.

Comparing government debt in 2024 to 2019, and then blaming the rise on Biden, is more than a little unfair, because Donald Trump was President in 2020. More than 100% of the increase in debt actually happened under Trump. In fact, federal government debt actually fell as a percent of GDP between Biden’s inauguration and the third quarter of 2024 (the most recent data available):

One reason government debt fell as a percent of GDP, of course, was because of inflation, which erodes the value of debt. But it seems very strange to blame Biden for a debt increase that happened under his predecessor.

As for the unemployment rate being higher in 2024 than 2019, this involves a bit of cherry-picking — in 2022 and early 2023, unemployment were as low or lower than they ever were before the pandemic:

Also, the unemployment rate is not the best measure of the health of the labor market, because it depends on who claims to be looking for work. In the Biden years, more prime-age (15-64) Americans claimed to be looking for work than in 2019 — probably because of the hot job market that Biden’s policies helped produce:

As a result, the prime-age employment rate1 — probably the cleanest single indicator of the U.S. labor market — reached an even higher level under Biden than it had under Trump:

These aren’t just little nitpicks — they illustrate fundamental tradeoffs that the Biden administration was facing, which the first Trump administration never had to face. One reason growth rates and the labor market were so good under Biden was because of the inflationary policies — in particular, deficit spending — that ran the economy hot. Had Biden spent less money on Covid relief and other stimulus, both GDP growth and the labor market likely would have been worse.

Furman dismisses the rapid growth of the Biden years. He writes:

Compared with other developed countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the United States saw a post-pandemic recovery that was about average in terms of real GDP growth versus pre-pandemic forecasts.

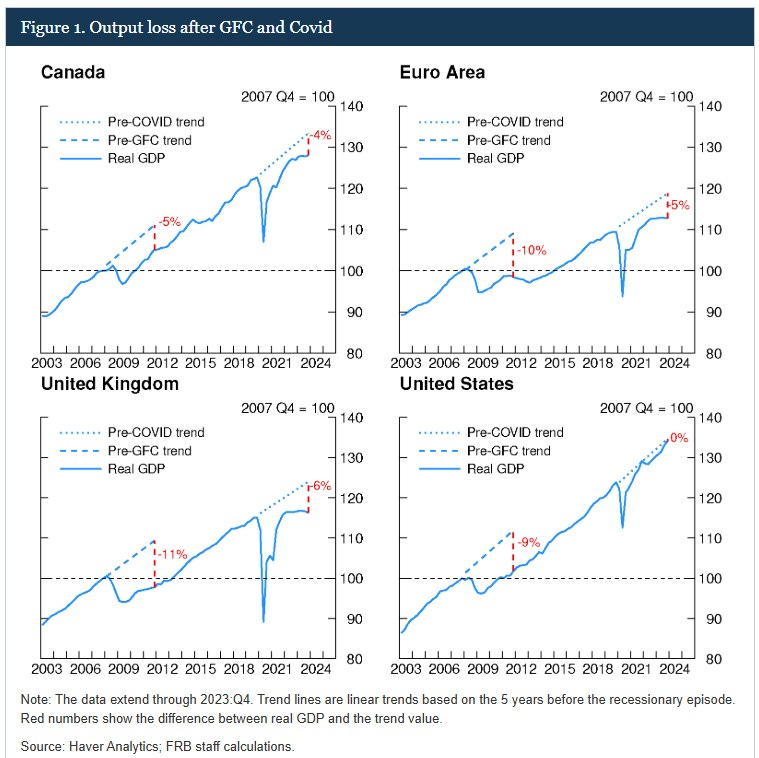

I’m not sure what “forecasts” Furman is referring to, but if you compare other rich economies relative to their pre-pandemic trends, the U.S. is the only one that has returned to trend:

Part of this is due to America’s superior productivity growth and greater immigration, and to Europe being hit by cutoffs of Russian gas. But de Sayres et al. (2024) show that countries that did more fiscal support in 2020 and 2021 ended up looking better relative to their pre-pandemic trends:

So I think Furman is quite possibly just wrong here.

As for inflation, Furman is absolutely right to identify this as the biggest economic problem of the Biden years. Those price rises ate away at Americans’ wages, incomes, and overall purchasing power, which was probably a big factor in the economic pessimism of the Biden years. And Furman is also right that the American Rescue Plan — Biden’s big Covid relief bill — probably exacerbated inflation, especially in 2021.

But by how much did Biden’s fiscal policies exacerbate inflation? There was other stuff going on at the same time — pandemic supply chain disruptions, shifts in consumer demand from services to goods and back again, the Ukraine war and an oil price spike, and so on. In addition, some portion of the excess demand in Biden’s term was a legacy of Trump’s pandemic spending, and of the various Federal Reserve loan programs that supported the economy through Covid. How much was actually Biden?

Macroeconomic estimates are always an incredibly imprecise science, but a number of researchers have all come up with fairly similar results:

Bianchi et al. (2021) predicted in advance that Biden’s ARP would raise inflation by around 2 percentage points in late 2021 and early 2022, and by about 1 percentage point in 2023.

Jordà et al. (2022) estimate that all pandemic fiscal support combined — not just Biden’s $1.9 trillion ARP, but also Trump’s $3.1 trillion from the CARES Act and a second bill — increased inflation by about 3 percentage points by late 2021.

Gordon and Clark (2023) estimate that demand shocks, interest rate shocks, and financial shocks all together raised inflation by about 2 percentage points in 2021 and 2022. It’s not clear what all those shocks are, but they represent an upper bound on the total effect of all the demand-side policies by Biden, Trump, and the Fed during the pandemic.

Shapiro (2022) finds that demand shocks — which again, include not just Biden’s fiscal policy, but also the delayed results of Trump’s pandemic spending, as well as the actions of the Fed — raised inflation by about 2.5 percentage points in late 2021 and 2022.

So if these estimates are in the ballpark, if Biden had made the ARP one-third as large as it was — as Furman suggests — it might have shaved at most 2 points off of U.S. inflation for maybe a year and a half. Recall that during that time, inflation was about 7 to 9 percent:

So a much smaller ARP likely would have resulted in that inflation being 5 to 7 percent instead. That’s better, but still substantial — it still would have caused declines in real incomes and wages, and it still probably would have made people pretty mad. It also would have still produced most of the policy headwinds that Furman talks about — more expensive materials for manufacturers and infrastructure, higher costs for service industries, and so on.

That doesn’t mean that Biden’s fiscal profligacy was unimportant — it was a big unforced error, and it definitely made things worse. But between supply-side factors and the lingering legacy of Trump’s spending and the Fed’s emergency programs, there were lots of other things pushing inflation up besides Bidenomics.

It’s also possible that the Fed would have felt less urgency about 5-7% inflation than it did about 7-9% inflation, and would have raised interest rates later or more modestly than it did. This might have slowed America’s rapid and successful conquest of inflation in the second half of Biden’s term:

Furman’s critique of industrial policy is also pretty hit-or-miss. He correctly notes that manufacturing employment hasn’t increased. The notion that industrial policy is about creating a bunch of good assembly-line jobs — which was a big part of how Biden sold industrial policy to the American public — is wrong. Even if hiring in manufacturing picks up as more factories come online, the total number isn’t going to be huge, because a lot of manufacturing is automated these days — in fact, in order to compete with China, America is going to have to go all-in on automation. So assembly lines will probably never again be a huge source of job growth.

But that doesn’t mean industrial policy hasn’t created blue-collar jobs! As Furman notes, there has been a big boom in factory construction. Construction booms require construction workers. And in fact, the Biden years saw a rapid increase in construction employment as a percentage of the total, to a level significantly higher than 2019 — and even higher than the 1980s and 1990s:

And Furman is on shaky ground when he argues that Biden’s industrial policy — focused on semiconductors, batteries, and some other strategic industries — simply ended up crowding out other manufacturing industries. He writes:

The manufacturing revival has run up against the problem of crowding out. By increasing subsidies for semiconductor fabrication and green technology innovation, for example, the government has encouraged their production. But these same policies, coupled with other fiscally expansionary policies, have driven up the prices of materials and equipment, wages for construction and factory workers, interest rates for entrepreneurs hoping to borrow, and the value of the dollar, all of which have made it harder for nonsubsidized manufacturing to prosper.

If this were true, we’d expect to see U.S. manufacturing construction be roughly flat — new factories in the semiconductor and battery industries would simply starve other manufacturers of labor, materials, equipment, and land, and the totals wouldn’t change much. But in fact, the Biden years saw huge increases in overall factory construction in America:

I’m also kind of confused by Furman’s argument that shifts in America’s industrial mix are inherently bad:

In fact, favoring some sectors while crowding out others likely increased the pace at which some companies have added jobs while others have shed them, leading to the very economic winners and losers that post-neoliberal critics complain result from expanded trade.

If any movement of workers from one industry to another is bad, then economic dynamism itself is bad. That doesn’t make sense. And if industrial policy takes workers away from flipping burgers or answering phones and sets them to work making things that will strengthen America’s national security (and potentially improve our export competitiveness), I don’t see how it helps to describe that as “winners and losers”.

Finally, Furman spends a lot of time arguing that Biden’s green industrial policy was inferior to a carbon tax. I suspect this is actually wrong, as I wrote back in 2022:

The short version of the argument is that subsidies leverage positive technological externalities more than carbon taxes do. Carbon taxes incentivize both scaling up of green technology and shrinking of the overall economy; green technology subsidies incentivize only the first of these.

But even if he were right about carbon taxes, Furman is simply ignoring the politics here. Carbon taxes have consistently struggled to gain political traction, probably because people’s willingness to endure cuts in their consumption in order to save the climate is extremely low. But green tech subsidies have succeeded in lots of places. When you’re choosing a climate policy, I think it’s good to take into account what people will actually accept.

All in all, this article felt a bit forced — not nearly as consistent and solid as Furman’s usual method of argumentation. And I think I know why. This is a pivotal moment in the future of the Democratic party and in left-of-center economic thought. The drubbing of 2024, and the soul-searching it led to, has created a window of opportunity to define the direction of the next decade. And Furman is correct that the new progressive economics of the Biden years will not be a strong choice overall.

But that’s not a reason to ignore the successes of the Biden years. The U.S. economy of 2024 was legitimately excellent, and Biden’s industrial policies are already teaching us important lessons about what’s possible and what works in terms of reindustrialization. Even if the new progressive economics has lots of flaws and went bust at the polls, there are still plenty of things we can learn from it.

In fact, I strongly agree with Furman’s concluding paragraph:

Rather than merely resorting to conventional approaches, however, what the country needs now is a renewal of economic policy thinking. The post-neoliberals were not wrong about the problems they inherited. Largely free labor markets have failed to deliver high levels of employment for prime-age workers in the United States for decades. National security concerns now shadow every question regarding trade and technology. And the transition to green energy will require dramatic action. New ideas about these old problems will never yield successful policies, however, if they dismiss budget constraints, cost-benefit analysis, and tradeoffs. It’s fine to question economic orthodoxy. But policymakers should never again ignore the basics in pursuit of fanciful heterodox solutions.

We do need a better economic model in America. And by embracing a sort of reactive anti-neoliberalism, the creators of the new progressive economics failed to fully rise to that challenge. But if we respond to that by embracing a reflexive anti-anti-neoliberalism, we’ll simply fail to learn the valuable lessons of the Biden years. I know everything feels very urgent right now, but it’s important that we think clearly and get these things right.

Also called the employment-population ratio.

One of the most telling statistics surrounding the 2024 election was that voters who spent time with the news in attempts to understand what was happening voted overwhelmingly for Biden/Harris. Those who had their heads in the sand or depended entirely on Trump friendly media went overwhelmingly for Trump.

Despite the fact that I took a couple of freshman classes in economics at the Wharton School at UPenn (coincidentally at the same time as a certain orange-haired self-described ‘stable genius' was also there) I am not even remotely an economic sage. But one thing is very clear to me. For us ‘amateurs’ the fact is that the number of economists who disagree with one another increases directly as the number of economists there are. Therefore we tend to be most influenced by our own experience of what is happening on the ground then by diverging ‘expert’ opinion.

But that doesn’t alter the fact that reading and making a valiant attempt to understand what’s going on is crucial to maintaining our Republic.

I remember one of those wonderful, often slightly alcohol fueled late-night college dorm discussions (albeit in the days before they could be co-ed). The topic, oddly enough was the importance of a good education. One of the disputants put it this way. "A good basic education should equip us to ask reasonable questions in a number of relevant areas, and, at least, to have a good idea when the answers we are getting back are bullshit".

I can’t think of a better nutshell description of one of the crucial reasons for the fix we find ourselves in now. And the continuing right wing attempts to denigrate the value of education outside what are generally considered ‘career-centered courses’ and to refuse the concept of ‘expertise’ is an excellent indication of one of the reasons why so many of us accepted all the bullshit we were getting from Trump and his myrmidons.

Curious your thoughts on the specifics of what a new new Democratic economic agenda should be