America has to feel fair

If people don't believe that anti-discrimination law protects them, they will turn to racial bloc politics.

According to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it’s illegal to discriminate against anyone based on race or sex. That includes discrimination against White men. If your company or your nonprofit or your university or your government agency tries to avoid choosing White men for a job position, you have violated American civil rights law. Every year, including under Democratic administrations, the U.S. government brings cases against employers for discriminating against non-Hispanic White people, and it often wins these cases (Example 1, Example 2, Example 3).

But having a law against racial discrimination doesn’t automatically get rid of it. Those cases are hard to win, they take a lot of time and money to prosecute, and a lot of plaintiffs probably don’t even know they can sue. It’s not clear how many Americans even understand that the Civil Rights Act protects White men in the first place.

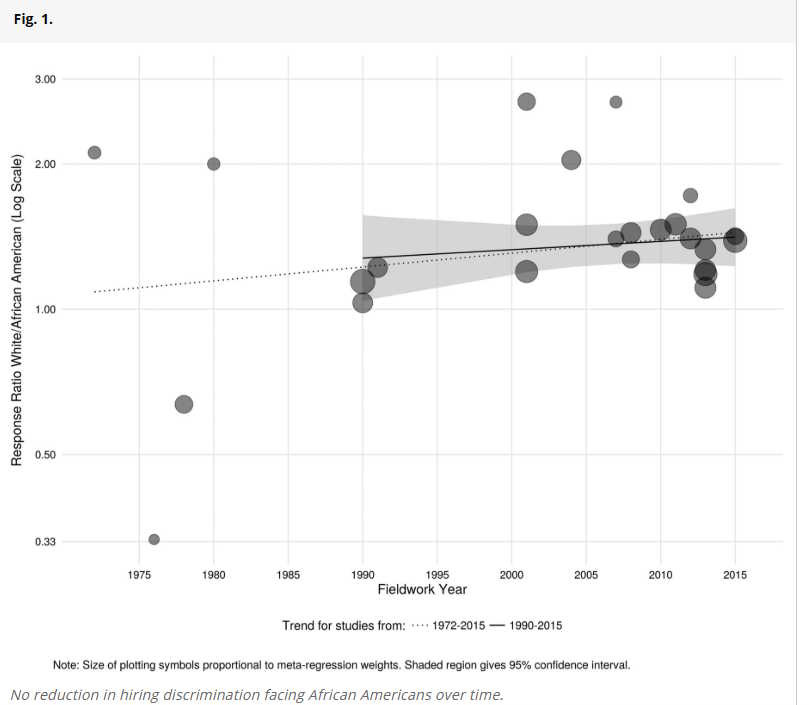

As an analogy, the U.S. government has been prosecuting anti-Black discrimination pretty vigorously for decades, but at least as of 2015, some still existed. A meta-analysis of field experiments by Quillian et al. (2017) found that employers in the early 2010s were still around 50% more willing to contact a White-seeming applicant for a job than a Black-seeming one:

(As a side note, the authors did find that discrimination against seemingly Hispanic candidates had fallen since the 1970s, and may have vanished entirely by 2015.)

So the law is not all-powerful. If a bunch of organizations in American society decide to discriminate based on race, the government has limited ability to stop them.

In a recent article titled “The Lost Generation”, Jacob Savage makes a convincing case that discrimination against White men rose significantly in America starting in the mid-2010s, and especially after 2020, especially in universities and the entertainment industry. Some excerpts:

The doors seemed to close everywhere and all at once. In 2011, the year I moved to Los Angeles, white men were 48 percent of lower-level TV writers; by 2024, they accounted for just 11.9 percent…White men fell from 39 percent of tenure-track positions in the humanities at Harvard in 2014 to 18 percent in 2023…

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death…The New York Times solemnly promised “sweeping” reforms—on top of the sweeping reforms it had already promised. The Washington Post declared it would become “the most diverse and inclusive newsroom in the country.” CNN pledged a “sustained commitment” to race coverage, while Bon Appétit confessed that “our mastheads have been far too white for far too long”…

These weren’t empty slogans, either. In 2021, new hires at Condé Nast were just 25 percent male and 49 percent white; at the California Times, parent company of The Los Angeles Times and The San Diego Union-Tribune, they were just 39 percent male and 31 percent white. That year ProPublica hired 66 percent women and 58 percent people of color; at NPR, 78 percent of new hires were people of color.

“For a typical job we’d get a couple hundred applications, probably at least 80 from white guys,” the hiring editor recalled. “It was a given that we weren’t gonna hire the best person… It was jarring how we would talk about excluding white guys.” The pipeline hadn’t changed much—white men were still nearly half the applicants—but they were now filling closer to 10 percent of open positions…

White men may still be 55 percent of Harvard’s Arts & Sciences faculty (down from 63 percent a decade ago), but this is a legacy of Boomer and Gen-X employment patterns. For tenure-track positions—the pipeline for future faculty—white men have gone from 49 percent in 2014 to 27 percent in 2024 (in the humanities, they’ve gone from 39 percent to 21 percent)…At Berkeley, white men were 48.2 percent of faculty applicants in the Physical Sciences—but just 26 percent of hires for assistant professor positions. Since 2018, only 14.6 percent of tenure-track assistant professors hired at Yale have been white American men. In the humanities, that number was just six out of 76 (7.9 percent).

This is only a tiny portion of the article, which runs to 9000 words. These numbers are a smoking gun in terms of racial and gender discrimination, but Savage also documents plenty of examples where institutions were quite open and explicit about their desire to avoid hiring white men. He also talks to some White men who succeeded in the face of this discrimination, and finds that everyone knew the discrimination was in full force.

I am no lawyer, so don’t take my word for this, but much of what Savage describes seems grossly illegal. Until the Supreme Court’s recent ruling, diversity was an acceptable reason to have racial preferences in university admissions, but to my knowledge it was never an acceptable reason to discriminate in hiring. If anti-discrimination law were easy to enforce, most of these universities and media businesses would be getting slapped with enormous fines (just as many more businesses would have been slapped with fines for discriminating against Black, Hispanic, or Asian people over the years). But anti-discrimination law is very hard to enforce — partly because the burden of proof is so high, partly because people who sue for discrimination risk being personally stigmatized. And so most of the perpetrators are likely to escape scot-free.

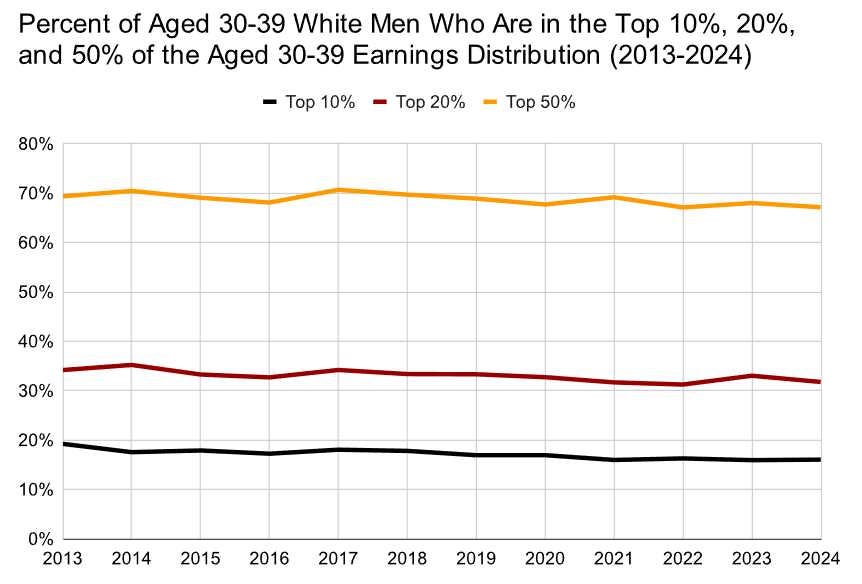

Some people have argued that anti-White discrimination is not a big deal, because White men are still doing well as a group. Matt Bruenig has a good post showing that aggregate economic outcomes for White men haven’t really declined in recent years. For example, the percent of young White men who land in the top percentages of the earnings distribution has declined, but only by a small amount:

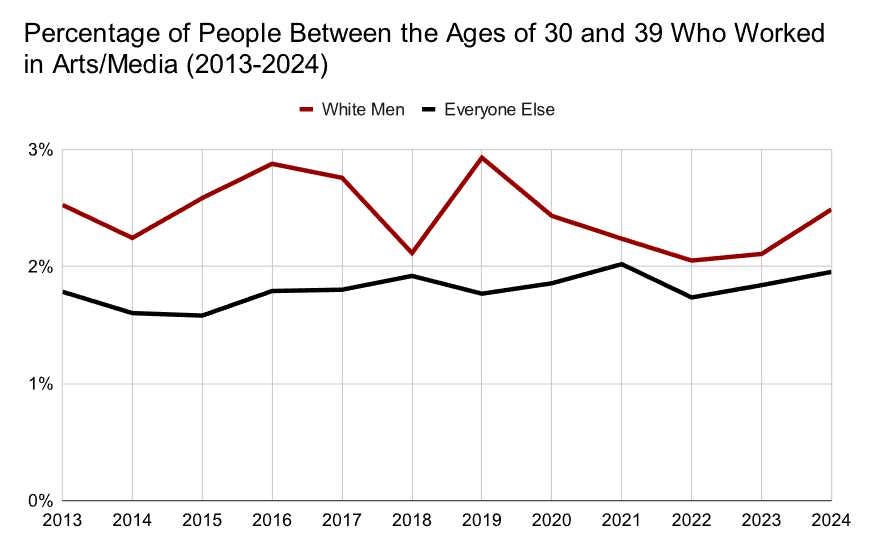

And the percentage of White men who work in arts and media bounces around, but has stayed around 2.5%:

Bruenig argues that to the extent that it seems that White men are vanishing from various occupations in America, this is due to the shrinking percent of White men in the American population.

Bruenig’s numbers help explain why the problem of discrimination against White men went unnoticed for so long. If you were in an industry or an institution that didn’t have much discrimination against White men, you could look around at wider society and still see White men succeeding at about the same rates as before. For example, I never personally encountered discrimination against White men in grad school — all the White guys I went to grad school with got good jobs, and all the people who ended up with the best jobs were White guys. Nor did I see anything at Stony Brook University or at Bloomberg.

There was thus nothing in my personal life to alert me to the increasing prevalence of discrimination against White men. And as Bruenig notes, the trend hadn’t yet shown up in aggregate statistics. So when I heard a few people start to complain on social media in the 2010s, I didn’t appreciate that anything had changed — especially because the people who complained tended to be the same right-wing types who were complaining about anti-White discrimination in the 2000s and the 1990s. The people who suffered personally from this discrimination — White men in progressive institutions and industries — were the ones who were most afraid to speak up about it.

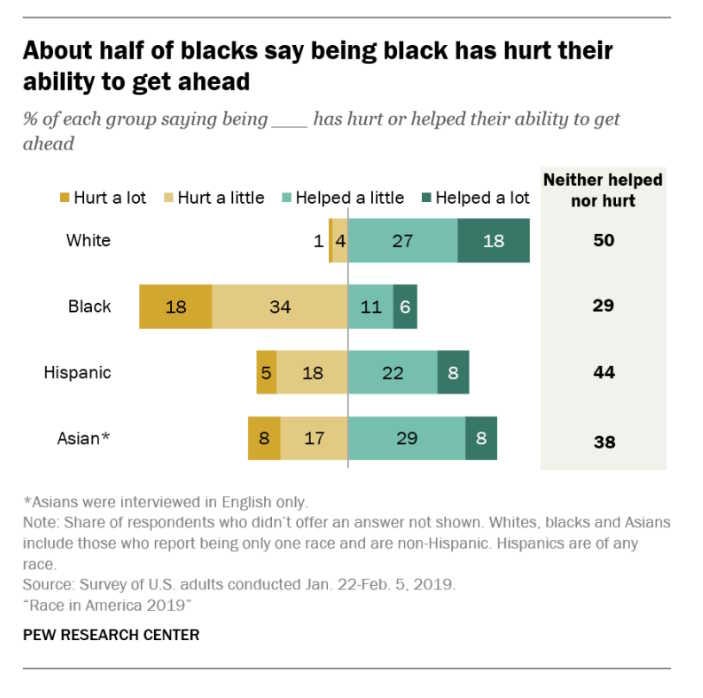

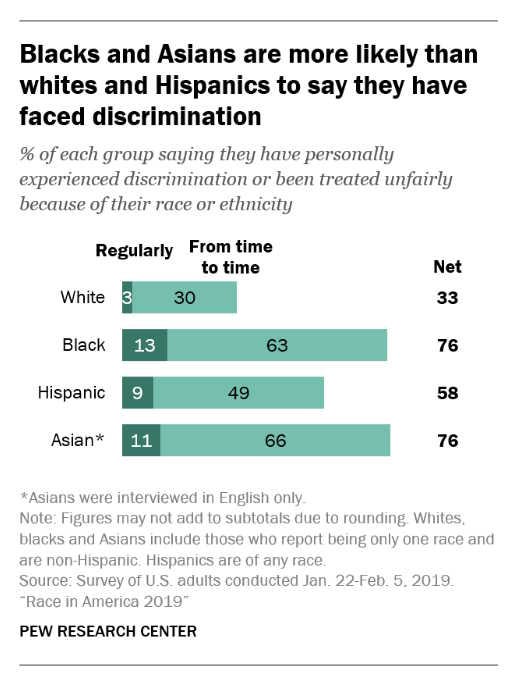

Nor was I unusual in my slowness to realize that something had shifted. As of 2019, almost no White Americans thought that being White made it harder for them to get ahead, and only a third of Whites said they had ever experienced racial discrimination:

It thus wasn’t until 2020 or 2021, when a flood of credible reporting came out about the new discriminatory trend, and when my friends in the tech industry started to talk openly about it, that I realized that something big had changed.

But Bruenig’s analysis, while praiseworthy for its attention to hard data (unlike much of the discourse around this topic), is not a convincing argument against Savage’s thesis. First of all, the shifts Bruenig documents are small but not trivial — a decrease in the percentage of young White men who make it to the top 10% from 20% to 17% can’t be explained by the shrinking percent of White men in the population. And showing that about the same number of White men work in arts and media over the years doesn’t tell us much about the quality, salary, prestige, or advancement opportunities of the jobs in which they’re working.

The real reason that Bruenig’s analysis shouldn’t mollify us, however, is that we shouldn’t treat aggregate group outcomes as the end-all and be-all of economic fairness.

The capitalist system is remarkably effective at allowing people to succeed in the face of discrimination. Although anti-Black discrimination in audit experiments has remained more or less constant over time, Fryer (2010) shows that in aggregate, anti-Black discrimination explains less and less of the racial gap in outcomes over time — once you control for education levels, racial inequality in the job market went way down in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. And Hsieh et al. (2019) argue convincingly that improved allocation of talent across racial groups has contributed to rising U.S. GDP. Some percent of hiring managers may still be suspicious when they hear a Black-sounding name, but discrimination doesn’t keep Black Americans down nearly as much as it used to.

By the same token, discrimination against White men can be pretty common, especially within certain industries, without keeping White men down as a group. Imagine that instead of quitting because of management changes and a run-in with the Chinese Communist Party, I had been kicked out of Bloomberg for being a White man. I make a lot more money with this Substack than Bloomberg ever paid me. So aggregate income statistics would have actually shown a gain for White men as a group. But I still would have been rightfully resentful, because discrimination would have forced me to go out of my way and take more risks and take a more non-traditional path to success.

(Note: I love Bloomberg, and they never discriminated against me in any way. This example was only for the sake of argument.)

In the same way, lots of American White men may have responded to a wave of discrimination since 2014 by going around the traditional employment system — starting their own businesses, working in non-traditional industries like crypto, and so on. And ultimately, in terms of income, many of them may have turned out fine — so many that the aggregate racial statistics show only a modest change. But those people are still fully justified in being angry at the unfairness of racial discrimination. And even if only a small percentage of White men had their careers destroyed by the wave of discrimination since 2014, that’s still a serious injustice.

This is also why discrimination against White men in academia, the media, or other progressive-dominated spaces is not a remedy for discrimination against Black people and women that still exists in some corners of American society. If half of American industries discriminate against White people and the other half discriminate against Black people, things may balance out at the aggregate group level, but lots of both White and Black Americans will still experience the sting of unfairness from being personally denied jobs they deserve, and from being kept out of the industries they want to work in.

Anti-White and anti-Black discrimination are not like matter and antimatter; they don’t just cancel each other out. An America where every job has racial preferences, and you have to look around for the jobs that favor your race instead of relying on individual merit and trusting the system, would clearly be a dystopia.

Aggregate group outcomes are not enough to make the American system feel fair. If I have my heart set on being a professor but I can’t get an academic job because I’m a White man, the fact that the richest billionaires in America are mostly White men will provide me with exactly zero comfort. People don’t succeed as racial blocs; they succeed as individuals. And fairness has to be provided at the individual level. That’s why laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 quite rightly make no reference to aggregate group outcomes. A feeling of individual fairness is what makes our system function.

Notice I said “feeling”. In practice, the widespread perception of fairness is only imperfectly correlated with actual procedural fairness. It’s very hard to tell when you’ve personally been discriminated against, since you only have a sample size of 1. If you get turned down for a job, how do you know how good the other applicants were? If you get fired, how do you know it was because of your race and gender, rather than your job performance, or your cultural fit, or some personal conflict with a coworker? And so on. It’s a difficult signal extraction problem.

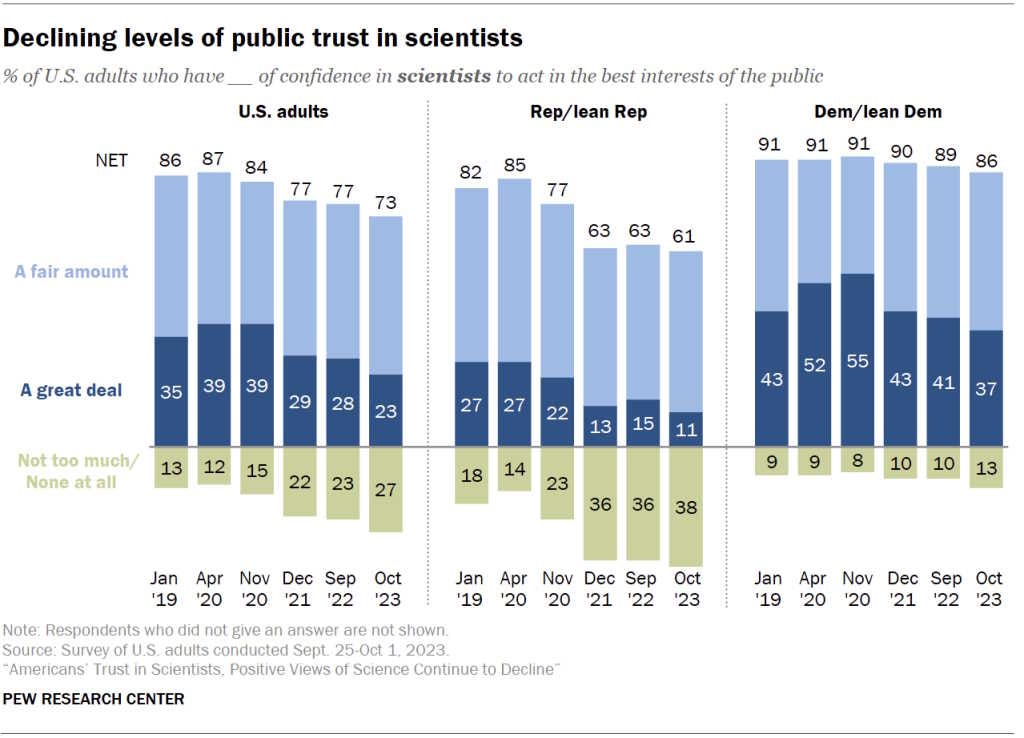

Discrimination can’t be eliminated. Instead, our goal should be to preserve trust in the system’s individual fairness. If people believe that the system is unfair, it will drive down trust in institutions and make it harder to provide public goods. One reason the second Trump administration is attacking academic science much more than the first Trump administration did is that Republicans’ trust in scientific institutions fell after 2020:

Some of that was related to Covid, of course, but some was probably due to the increased racial and gender discrimination that Jacob Savage’s article documents. It was not simply a function of right-wing media ginning up hysteria. It was real.

If we want to preserve or rebuild trust in America’s institutions, we have to make the bulk of people believe that those institutions are broadly free of discrimination.

How can that be accomplished? There’s no perfect solution. Even if institutions can be made more race-neutral and gender-neutral, the memory of the period of intense discrimination will persist for a long time. And opportunistic political agitators, amplified by social media, will continue to tell everyone that the system is unfair no matter how much we manage to curb the actual unfairness.

But I think there is one way we can make the system seem more fair, and that’s to aggressively and publicly enforce the law. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbids racial discrimination, and in some cases the 14th Amendment does too. So the best solution, I think, is to have lots of high-profile legal victories that make it clear to all Americans that racial and gender discrimination are prohibited in the United States. I wrote about this back in May:

Formal equality under the law does not guarantee actual fairness in society. The law is not all-powerful. But it’s a big loud public signal that says that the system disapproves of unfairness. Therefore, the best remedy for discrimination against White men is simply for White men who feel they’ve been discriminated against to sue, and sue, and sue again.

The alternative to individual fairness under the law is group racial conflict. If Americans decide that individual fairness is dead, and that their interests can only be served by collective racial “power” movements, then we will see the Republican party morph into a White power party, and the Democratic party morph into a “BIPOC” power party.1 Racial bloc politics will be very bad for the country’s future.

America already has good laws that mandate individual fairness. If those laws can be enforced in a very public and unambiguous way, then I think we may still escape the dystopian future of racial conflict and balkanization.

Or should I say, continue to morph, since we’ve already gone somewhat down this road.

"Discrimination can’t be eliminated. Instead, our goal should be to preserve trust in the system’s individual fairness."

It was achieved in tech by standardizing interviews in many tech companies and training interviewers against bias. It's not perfect, but no one says someone got into Google as an engineer because of their race or gender or sexual orientation.

Universities need to push for making standardized tests harder and giving it more weightage. Standardization, whether it's for hiring standards or admissions, is the only way to improve the perception of fairness, even though some bias will always exist.

When I was in grad school in the physical sciences, in the 70’s, gender discrimination against women was horrendous. When men ran into problems in their research, they were supported and encouraged. Women facing the same problems were told that they were inadequate, and they constantly got the message that they were unlikely to succeed. The predictable result was a much higher attrition rate for women, with hardly any completing their PhD programs.

I have no doubt that today there is discrimination against white men, but I tend to see this is an understandable overcorrection from some pretty troubling behaviors in the past. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t address it, but does ask for some tolerance and patience.

I should mention that racial discrimination was never an issue because there were exactly zero minority applicants to that program. The discrimination happened upstream of the graduate program.