What happens when we gut federal science funding?

An experiment I would prefer not to conduct.

Back at the beginning of his first term in 2017, Trump briefly tried to cut federal science spending. I wrote a pair of posts for Bloomberg saying that this was a bad idea. Here are some excerpts from the first of those:

Support for science and technology is one of the key functions of a modern, rich-country government. Developed nations like the U.S. are at the technological frontier. It’s hard for them to grow by imitating or catching up to other countries, so in order to advance, they have to improve productivity. But productivity growth has been slowing noticeably…Research shows that most scientific and technological fields require more money and manpower to maintain the same rate of progress as time goes on…Unfortunately, federal research spending in the U.S. has leveled off…

Even most free-marketers recognize that the government has a key role in basic research and technology. The private sector won’t pick up the slack -- private companies are great at turning research into commercial products, but bad at doing pioneering scientific work. This is because it’s hard for companies to capture the fruits of research spending -- science is a public good. The U.S. high-tech economy works well because it has a pipeline -- government and universities do the basic research, while companies commercialize the science that emerges. Cutting off the first part of the pipeline will strangle American industry, leaving rivals in Asia and Europe to dominate the industries of the future.

And in the second post I waxed lyrical about how abandoning science can lead to civilizational decline:

To understand why science is so important, it’s essential to take a broad view of history…Science was…the secret sauce of Western civilization…

During the Middle Ages, the Islamic empire under the Abbasids of Baghdad boasted many of the world’s leading thinkers, some of whom were experimenting with ideas eerily similar to those eventually embraced by European scientists. But for some reason, the Caliphate turned away from these ideas. No one knows exactly why, but many blame the rise of anti-scientific and anti-rationalist schools of thought…

Another frustrating historical example is China’s Ming Dynasty. China…in the 15th and 16th centuries it was the world’s most technologically advanced civilization. Proto-science was common in early modern China, but the country cut itself off from foreign influences and de-emphasized science in the civil-service examinations. Eventually, China ended up importing Jesuit astronomers from Europe…

If there’s something that makes the U.S. and other modern developed nations more successful than those old empires, it’s not the strength of their armies or the superiority of their religious beliefs -- it’s a healthy respect for the march of systematically acquired knowledge of the natural world.

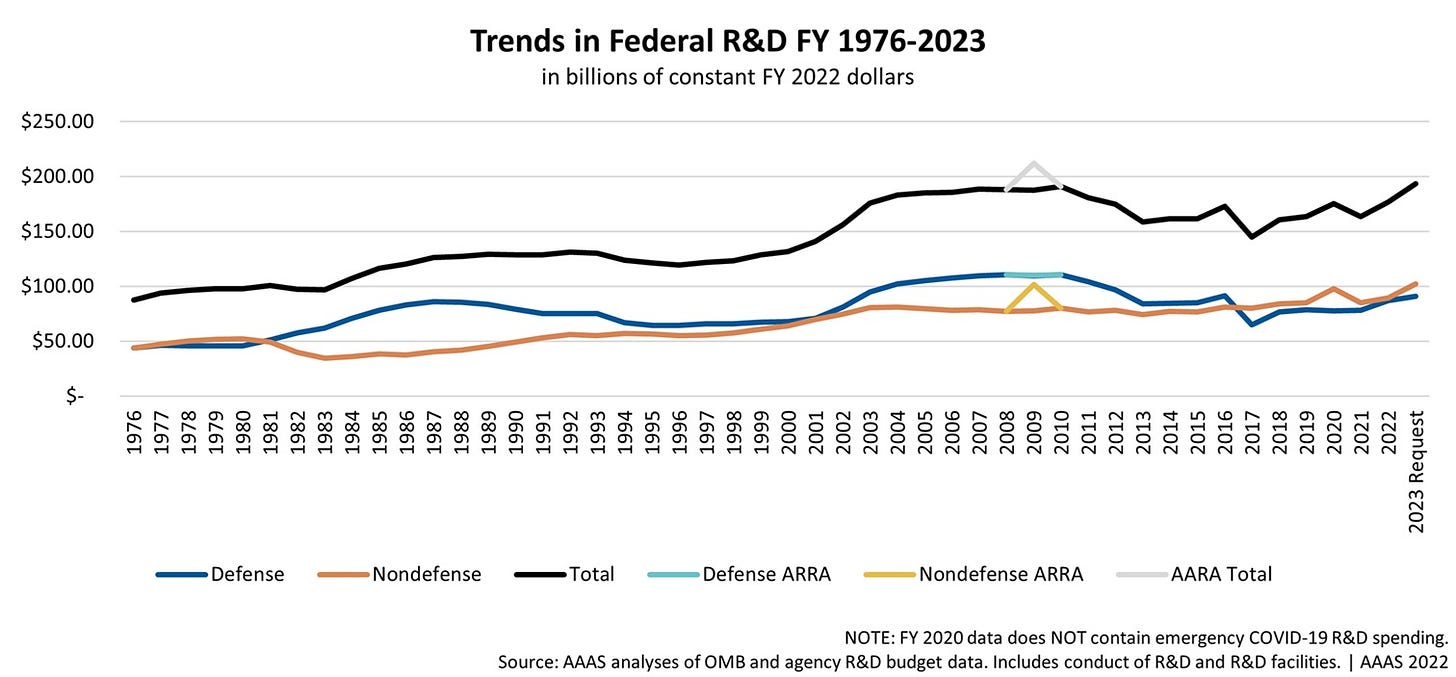

But as with so many of Trump’s threatened disruptions to the American system in his first term, this one never actually materialized. Nondefense R&D spending actually rose, while research spending stayed constant as a fraction of GDP. Defense R&D spending — mostly “development” rather than basic research — took a cut as the military allocated money toward other priorities, but recovered over the rest of Trump’s term:

In fact, the big cuts to federal defense-related development spending came under Obama, Clinton, and George H.W. Bush.

Things may not go the same way this time around, though. In his second term, Trump is issuing deeper and more far-reaching executive orders than in his first. And he now has Elon Musk on his team — a man whose ability to get things done is unparalleled. As a result of Trump’s executive orders and Musk’s layoffs, federal science funding in the United States has been abruptly thrown into chaos.

First, Trump issued an executive order suspending almost all grants from the National Institutes of Health — the U.S.’ biggest government research funding agency other than the DoD. When a court ordered the funding to resume, the Trump administration found other ways to hold up funding. This is from Nature:

About a month after Donald Trump took office…almost all grant-review meetings remain suspended at the…NIH…preventing the world’s largest public funder of biomedical research from spending much of its US$47-billion annual budget…These review panels are suspended because the Trump administration has barred the agency from taking a key procedural step necessary to schedule them. This has caused an indefinite lapse in funding…The Trump administration issued an order on 27 January freezing payment on all federal grants and loans, but lawsuits challenging its legality were filed soon afterwards, putting the order on hold. However, payments are still not going out, because Trump’s team has halted grant-review meetings, exploiting a “loophole” in the process[.]

Trump also issued an order that would severely limit the NIH’s ability to pay “indirect costs” — i.e., payments to support infrastructure and personnel at the labs that actually do the government-funded research. A judge has also blocked that order, but Trump may find another creative way around the courts. As a result of these orders, NIH funding has been mostly halted, or at least severely delayed.

Meanwhile, Musk’s DOGE has been firing a bunch of “probationary” workers at the science agencies:

As the administration seeks radical changes to research funding, it has also sought to cut employees at federal scientific agencies…Wide-ranging cuts of probationary workers — who are typically in their first year of employment at federal agencies and not yet subject to the same job protections as more tenured staff members — have hit almost every corner of the government…Hundreds of employees at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were let go…Similar shake-ups are anticipated at other science agencies, including NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which manages the National Weather Service…Employees at the National Science Foundation (NSF) have been told that up to half of the agency’s staff could be laid off soon…Matt Brown, the recording secretary for NIH Fellows United, a union that represents about 5,000 fellows, said NIH staffers were let go on Friday.

On top of all these executive orders and firings, Trump is reportedly planning to ask Congress to cut science funding by a substantial amount:

[T]he White Houses’ first budget request of Donald Trump’s second term could be a fiscal reckoning for America’s government scientific enterprise. The National Science Foundation, a cornerstone of the country’s research infrastructure with its annual $9 billion purse, might face particularly savage cuts…intelligence from within the administration suggested the agency’s budget could be slashed by up to two-thirds, potentially shrinking to a mere $3 billion.

In other words, the attack on science funding that was successfully deterred back in Trump’s first term may become a reality in his second.

This is an ideological purge of the scientific establishment

Why is this happening? Why are our leaders suddenly and willfully smashing one of the core institutions that made America the world’s leading nation over the past century?

The most likely answer is a very simple one: Like many of the Trump administration’s early actions, it’s an ideological purge. Trump and Musk have decided that America’s scientific establishment is a hotbed of woke ideology that needs to be torn out root and branch, regardless of the damage to the country’s strength in science and technology. This is from an article in Physics World:

In response to [Trump’s executive] orders, government departments and external organizations have axed diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programmes, scrubbed mentions of climate change from websites, and paused research grants pending tests for compliance with the new administration’s goals…

Even before they had learnt of plans to cut its staff and budget, officials at the NSF were starting to examine details of thousands of grants it had awarded for references to DEI, climate change and other topics that Trump does not like…

Trump’s anti-DEI orders have caused shockwaves throughout US science…NASA staff were told on 22 January to “drop everything” to remove mentions of DEI, Indigenous people, environmental justice and women in leadership, from public websites. Another victim has been NASA’s Here to Observe programme, which links undergraduates from under-represented groups with scientists who oversee NASA’s missions…

Anti-DEI initiatives have hit individual research labs too…Fermilab – the US’s premier particle-physics lab – suspended its DEI office and its women in engineering group in January. Meanwhile, the Fermilab LBGTQ+ group, called Spectrum, was ordered to cease all activities and its mailing list deleted. Even the rainbow “Pride” flag was removed from the lab’s iconic Wilson Hall.

This isn’t surprising. Republicans already had significantly lower trust in science before 2020, probably because scientists tend to be progressives. But that trust took a big hit after the Floyd protests and the subsequent proliferation of “woke” culture across America’s elite institutions:

Now, it’s not like the Republicans are wrong about much of America’s scientific establishment being “woke”. Remember that the fundamental fact of American politics is education polarization — the higher a degree someone in the U.S. has, the more likely they are to be a Democrat and a progressive. Before 2020, you could be a progressive in good standing while still opposing systematic racial discrimination against white people in hiring, promotion, funding, and so on; after 2020, it became much harder.

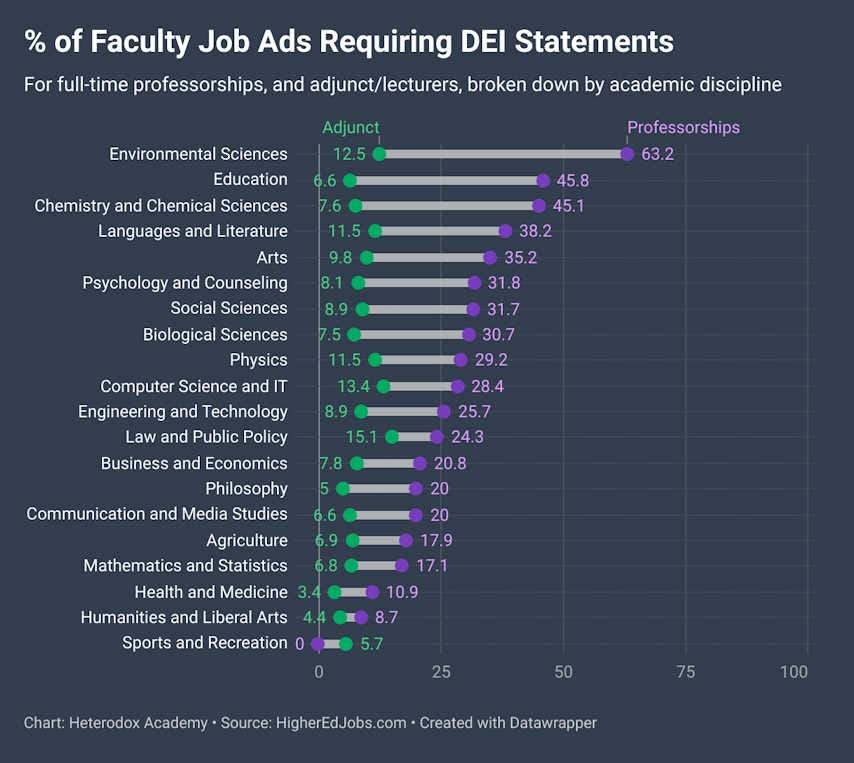

Conservative journalists like Aaron Sibarium of the Washington Free Beacon and John Sailer of the Manhattan Institute have been relentlessly chronicling examples of this over the past few years, and there really are a lot of them. Lots of science departments at universities made prospective hires sign DEI statements. This is from a 2024 study of academic job postings by Nate Tenhundfeld:

Racially discriminatory hiring practices are hard to measure, but they appear to have become fairly commonplace in the sciences. Some of these examples are blatant and explicit. Others quietly rely on DEI statements, punishing applicants who refuse to discriminate on the basis of race. Here’s John Sailer in the WSJ:

Through public-records requests, I acquired the rubrics for evaluating diversity statements used by two NIH-funded programs. The University of South Carolina’s program currently seeks faculty in public health and nursing. The University of New Mexico’s program seeks faculty studying neuroscience and data science. Both programs use virtually identical rubrics for assessing candidates’ contributions to diversity, equity and inclusion…The South Carolina and New Mexico rubrics call for punishing candidates who espouse race neutrality, dictating a low score for anyone who states an “intention to ignore the varying backgrounds of their students and ‘treat everyone the same.’ ”

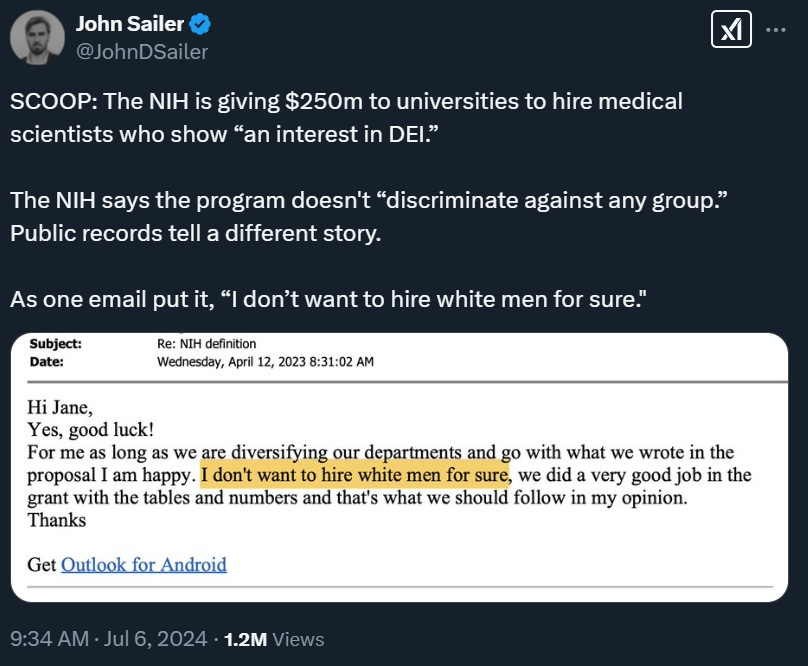

The federal granting agencies have been fairly heavily involved in this. In another article, Sailer notes that the NIH actually requires DEI statements as a condition of some of its science funding programs. He also discovered emails at the NIH espousing explicit racial discrimination:

Honestly, this stuff is just egregious. I’m no lawyer, but it seems like if racially discriminatory admissions at government-funded universities are illegal under the Fourteenth Amendment, then racially discriminatory granting practices and racial discrimination in hiring at government-funded science departments are probably not going to pass constitutional muster either.

More importantly, turning science into an explicit racial spoils system is not going to be good for either science or race relations in America. In a multiracial democracy like ours, it’s important that every racial group believe that they’re being treated fairly and equally by the system. If one group is clearly being discriminated against by the country’s institutions, it not only causes resentment among that group, but also engenders worry among other groups that they might be next.

Even beyond the narrow issue of racial discrimination, political activism by members of the scientific establishment are decreasing Americans’ trust in science. This is from Alabrese et al. (2024):

The study measures scientists’ polarization on social media and its impact on public perceptions of their credibility…An experiment assesses the impact of online political expression on a representative sample of 1,700 U.S. respondents, who rated vignettes with synthetic academic profiles varying scientists’ political affiliations based on real tweets. Politically neutral scientists are viewed as the most credible. Strikingly, on both the ’left’ and ’right’ sides of politically neutral, there is a monotonic penalty for scientists displaying political affiliations: the stronger their posts, the less credible their profile and research are perceived, and the lower the public’s willingness to read their content.

Seen in the light of research like this, the merging of science and political activism over the last decade has been a disaster for one of America’s most important institutions. In 2015, most Americans of both parties believed that scientists are politically neutral. Now that hard-won reputation for objectivity has been damaged.

Now that doesn’t mean it’s worth gutting one of America’s most important and effective institutions, just to get rid of wokeness. In fact, I think it’s very much not worth it; the culture of science is less important than the productivity benefits it creates for our nation. On top of that, DEI stuff was already on the wane, and more scientists were already speaking up about the importance of objectivity well before Trump was elected. I really dislike politicized science, but I don’t think the Trump administration’s slash-and-burn approach is the right response.

But I think what we’re learning is that the American right has decided to start defecting in the repeated prisoner’s dilemma that defines our social relations. Conservatives have decided that the benefits science brings to America are not worth it if the culture of science makes America less of the kind of nation they want to live in.

For this reason, I hope Trump’s purge fails, but I also hope that the scientific establishment responds to the purge by simply ditching the politicized crap of 2020-2024 and returning to a stance of political neutrality.

So what does happen if the U.S. guts federal science spending?

It’s important to recognize that talk of a science apocalypse in the U.S. may be premature. It’s likely that once this purge is complete and wokeness has been culled to his satisfaction, Trump will un-pause federal grants. He may even hire more employees at the granting agencies to replace the ones who were fired. And the proposed NSF budget cuts may not end up making it through Congress, just as happened in Trump’s first term. There’s still a slim chance that this will end up being a false alarm.

But if it’s not, what happens to our economy? Most economists are in agreement that the economic benefit of research spending is well worth the cost. A 2009 literature review by Hall et al. found that “in general, the private returns to R&D are strongly positive and somewhat higher than those for ordinary capital, while the social returns are even higher, although variable and imprecisely measured in many cases.” More recent research agrees. Jones and Summers (2020) show that if you assume R&D spending is solely responsible for new technologies (rather than, say, unfunded tinkerers inventing stuff in their garages), then society benefits enormously from every dollar spent.

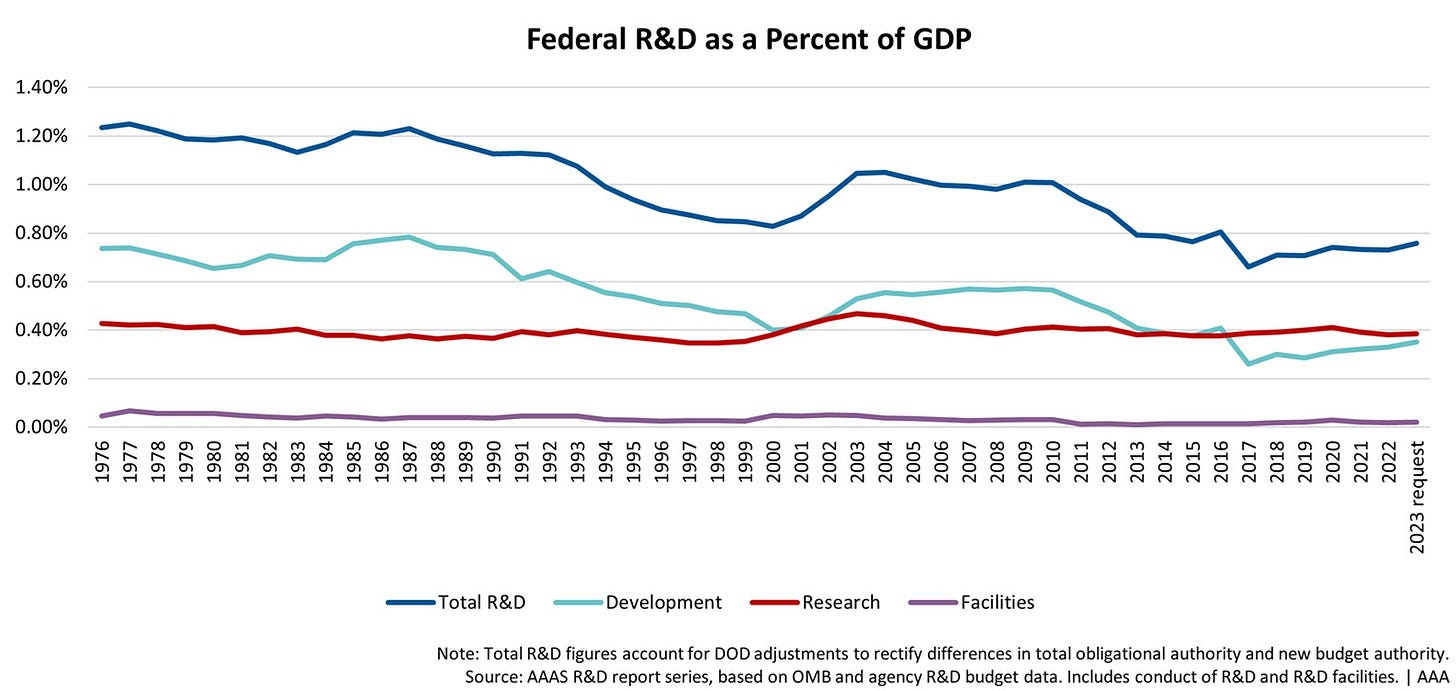

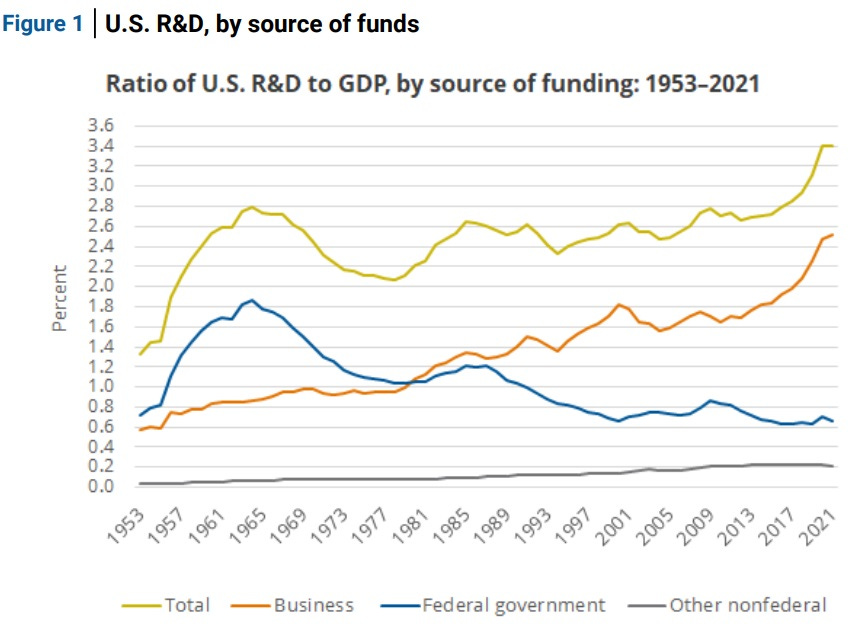

But that glosses over a crucial question: How important is federal government research spending, specifically? Conservatives might question whether private companies will pick up the slack if the federal government steps back. In fact, this has been happening for decades — as federal R&D spending has fallen as a share of GDP since the 1960s, private R&D spending has stepped in to fill the gap:

The list of federally funded scientific breakthroughs and groundbreaking inventions is certainly long — everything from AI and the internet and smartphones to Crispr and mRNA vaccines to GPS satellites and the microprocessor. But that doesn’t tell us the counterfactual. It’s theoretically possible that without federal funding, corporate labs would have come up with these inventions — or better ones — even earlier.

Some economists actually do think that. For example, Arora et al. (2023) find that an increase in federal R&D funding in a field tends to reduce corporate R&D spending in that field — a case of “crowding out”. They also argue that federal spending is less efficient in purely economic terms, because some basic science represents abstract knowledge that never makes it into any practical invention. The authors then speculate that some of the productivity slowdown of recent decades might be happening because research has shifted from private to public:

The sluggish growth in productivity over the last three decades or more in the face of sustained growth in scientific output has puzzled observers. Our findings point to a possible reason…The limit on growth is not the creation of useful ideas but rather the rate at which those ideas can be embodied in human capital and inventions, and then allocated to firms to convert them into innovations. In other words, productivity growth may have slowed down because the potential users — private corporations—lack the absorptive capacity to understand and use those ideas. The loss of absorptive capacity is partly related to the growing specialization and division of innovative labor in the U.S. economy. Not only do universities and public research institutes produce the bulk of scientific knowledge, but over the past three decades, publicly funded inventions and startups have grown in importance as sources of innovation. Concomitantly, many incumbent firms have substantially withdrawn from performing upstream scientific research. The withdrawal of many companies from upstream scientific research may have reduced their absorptive capacity—their ability to understand and use scientific advances produced by public science.

But I think you should be very suspicious of these conclusions. Notice that Arora et al. claim that “publicly funded inventions and startups have grown in importance as sources of innovation.” But now look at the chart I posted above, and remember that private sector R&D has actually increased massively as a share of GDP, even as federal funding has withered and shrunk. So either Arora et al. are just plain wrong, and are trying to explain facts that don’t exist, or the “and startups” part of their sentence is doing all of the work there.1

In fact, federally funded R&D often benefits the economy by creating startups. Babina et al. (2020) find that federal R&D generates a lot of startups, which spin out of university research projects, or make heavy use of academic discoveries:

We find that federal and private funding are not substitutes. A higher share of federal funding causes fewer but more general patents, more high-tech entrepreneurship, a higher likelihood of remaining employed in academia, and a lower likelihood of joining an incumbent firm… Together with evidence from industry contracts, the effects support the hypothesis that private funding leads to greater appropriation of intellectual property by incumbent firms. Privately funded research outputs are more often patented, while federally funded research outputs are more likely to end up in high-tech startups founded by graduate students.

And Tartari and Stern (2021) find that federal government research is unique in serving this function:

Our key finding is that changes in Federal research commitments to universities are uniquely linked to positively correlated changes in the quality-adjusted quantity of entrepreneurship…Research funding to universities seems to play a unique role in promoting the acceleration of local entrepreneurial ecosystems.

In other words, these papers find that the more that research spending in America is dominated by big companies, the more the resulting innovations will get patented and locked away inside the bowels of a Google or a Pfizer or a General Motors, where the rest of the economy can’t use them as much. But the more that the federal government funds university research, the more that new inventions enter the economy via dynamic new fast-growing companies that compete against the aging behemoths.

In other words, the U.S. economy’s increasing reliance on private R&D spending — most of which is done by big companies — could be making it harder for scrappy startups to disrupt the incumbents. This could be taking the U.S. in the direction of countries like Japan, Korea, and Germany, where big old corporations dominate the landscape. Trump’s cuts to federal science will probably end up hurting the “little tech” that Marc Andreessen likes to talk about.

As for the effect of federal funding on productivity — i.e., what we ultimately care about — most papers find that it’s big and positive. For example, Fieldhouse and Mertens (2023) find really huge effects:

We estimate the causal impact of government-funded R&D on business-sector productivity growth…Using long-horizon local projections and the narrative measures, we find that an increase in appropriations for nondefense R&D leads to increases in various measures of innovative activity, and higher productivity in the long run. We structurally estimate the production function elasticity of nondefense government R&D capital…and obtain implied returns of 150 to 300 percent over the postwar period. The estimates indicate that government-funded R&D accounts for about one quarter of business-sector TFP growth since WWII, and generally point to substantial underfunding of nondefense R&D. [emphasis mine]

Their methods are a bit unorthodox, but Dyevre (2024) uses more standard methods and obtains broadly similar results:

Using a novel firm-level dataset…covering 70 years (1950-2020), I estimate the impact of the decline in public R&D in the US on long-run productivity growth. I use two instrumental variable strategies…to estimate the impact of the decline in public R&D on the productivity of firms through technology spillovers. I find that a 1% decline in public R&D spillovers causes a 0.03 to 0.08% decline in firm TFP growth. Public R&D spillovers appear to be two to three times as impactful as private R&D spillovers for firm productivity. Moreover, smaller firms experience larger productivity gains from public R&D spillovers. [emphasis mine]

In other words, although there’s not an absolute consensus in the economics field, most researchers find that federally funded R&D is incredibly important for U.S. productivity growth. The decline in federal spending has made it harder for the U.S. economy to sustain the kind of productivity gains it saw in earlier decades.

Even the seemingly silly government-funded research projects that conservatives love to make fun of — shrimp running on treadmills! — often result in very practical discoveries. Jim Pethokoukis of the American Enterprise Institute lists a few:

[R]esearch into frog skin secretions unlocked the mysteries of fluid absorption, paving the way for oral rehydration therapy. The payoff has been nothing short of remarkable: over 70m lives saved, most of them children in developing nations…Scrutinizing fly reproduction yielded an elegant solution to America’s livestock pest problem: the sterile screwworm fly. This peculiar triumph of entomology now saves ranchers $200m annually…When scientists first examined Gila monster venom, they were hardly dreaming of treating diabetes and obesity. Yet this toxic cocktail held the key to developing GLP-1 agonists like Ozempic. Maybe you’ve heard of this drug?

On top of the productivity benefits, federally funded scientific research has major national security implications. Not only does some DoD spending go directly to creating militarily useful technologies that help preserve America’s technological edge over China, but more research funding in general will be needed to compete with China’s massive push to become the world’s leading scientific power. Right now, on some popular measures of scientific research output, America is being left in the dust by our main rival:

Seen in this context, Trump and Musk’s assault on research spending looks to be part of the unilateral disarmament and deindustrialization that is rapidly becoming this administration’s hallmark.

So if Trump and Musk care at all about the wealth and security of the nation, they need to turn the science funding taps back on as quickly as possible. I understand that they feel the need to purge woke culture from the system, but that purge needs to finish before it becomes too late to save American scientific prowess. The clock is ticking.

In fact, it’s probably both of these things.

This is a great post but Musk doesn't read the column.

Now, some follow up.

I think you are imputing too much faith in the Anti DEI justification for torching federal research.

Republicans and corporate aligned people have been hostile to basic science since it was white men in white coats saying, "Actually, nicotine is addictive and smoking kills". Anthropogenic climate change has been widely scientifically accepted since the 1980s and well funded efforts to deny/discredit the science have been around since then too. It goes even older than that with religious authorities, mostly on the right trying to discredit research saying that people evolved or the earth is billions of years old.

Reagan didn't pull Carter's solar panels off the white house because of DEi programs in 2005.

The "Why did those awful DEI people make the Right do this" tone of the piece is thus a bit overblown.

It was a useful bit of overreach that provided the Right an opening to enact an agenda that has been going on for decades.

As you do read Scott Alexander and are probably familiar with Elizier Yudkowsky, I wanted to leave a quote which I think is more reflective of Trump/Musk's actual purpose. (Though some left people have this pathology as well)

"Lies propagate, that's what I'm saying. You've got to tell more lies to cover them up, lie about every fact that's connected to the first lie. And if you kept on lying, and you kept on trying to cover it up, sooner or later you'd even have to start lying about the general laws of thought.

Like, someone is selling you some kind of alternative medicine that doesn't work, and any double-blind experimental study will confirm that it doesn't work. So if someone wants to go on defending the lie, they've got to get you to disbelieve in the experimental method. Like, the experimental method is just for merely scientific kinds of medicine, not amazing alternative medicine like theirs. Or a good and virtuous person should believe as strongly as they can, no matter what the evidence says. Or truth doesn't exist and there's no such thing as objective reality.

A lot of common wisdom like that isn't just mistaken, it's anti-epistemology, it's systematically wrong. Every rule of rationality that tells you how to find the truth, there's someone out there who needs you to believe the opposite. If you once tell a lie, the truth is ever after your enemy; and there's a lot of people out there telling lies."

I agree with Matthew that this is much deeper than DEI, which could be eliminated without gutting the entire enterprise. Authoritarians need to break any source of legitimacy other than their word and science does that in spades. You also left out that once the scientific edifice is broken, it would take decades if ever to build it back. I used to work at Bell Labs and I have worked for decades within the academic biomedical field. Every research field has many sub specialists not just in the knowledge but the skills in making things work. Once that is gone, it is gone.