Where does a liberal go from here?

Our movement overreached and crashed. But the fundamental ideals are still just as powerful.

“You," Said Dr. Yavitch, "are a middle-road liberal, and you haven't the slightest idea what you want.” — Sinclair Lewis

Imagine being a French liberal in the year 1815. You spent your youth dreaming of an end to tyranny and the stultification of the estate society, reading the works of Voltaire and Rousseau and Montesquieu and Diderot, talking of liberty with your friends in cafes. Yours was not among the names that history would remember from that era, but you once attended a salon in a rich woman’s house in Paris. You were not part of the mob that stormed the Bastille in 1789, but you felt your heart leap when you heard the news, because you knew that now everything would change. When you read the terms of the Constitution of 1791, you saw the fulfillment of your youthful daydreams become the solid fabric of a new reality.

Imagine, then, standing in 1815, a quarter century after the Revolution, looking back at what it had all become. That first bright rush of freedom had given way, first to the murderous insanity of the Terror and the Committee for Public Safety, then to the thuggish new imperialism and endless bloody wars of Napoleon, and finally to the fall of all Europe to conservative reaction under the Congress of Vienna. Imagine looking back on the arc of your beliefs, your movement, and your life, now as an old man, with no prospects for another, better Revolution ahead of you.

Would you think your dreams had failed? Would you decide that everything you had believed had been an illusion, and that freedom, democracy, and the Rights of Man were false idols that led only to chaos and bloodshed?

If so, you would be utterly wrong. The two centuries after 1815 would see the ideals of the early French Revolutionaries continue to advance across the world — unevenly, in fits and starts, and with many reversals, yet almost always leaving society better off than before. Those centuries would also see plenty of successors to Robespierre and Napoleon, but just like the originals, they would usually go down to defeat or see their legacies overturned by people weary of war and oppression. Liberalism may have lost the first French Revolution, but it ended up winning the world — at least, for a while.

I think about this a lot when I reflect on the liberal dreams of my own youth.

I was raised a liberal, in late 20th century America. My parents were the kind of center-left Democrats who disgusted Cold War revolutionaries and conservatives alike — bookish academic types who hated Stalin but viewed Martin Luther King, Jr. as a prophet, who believed in private property and the welfare state, who protested the Vietnam War but hung an American flag in front of the house every year on the Fourth of July and Memorial Day and Veterans Day. My father told me George H.W. Bush was a good man, but when he won the election in 1988, my mother cried and said “Thank God for Teddy Kennedy.”

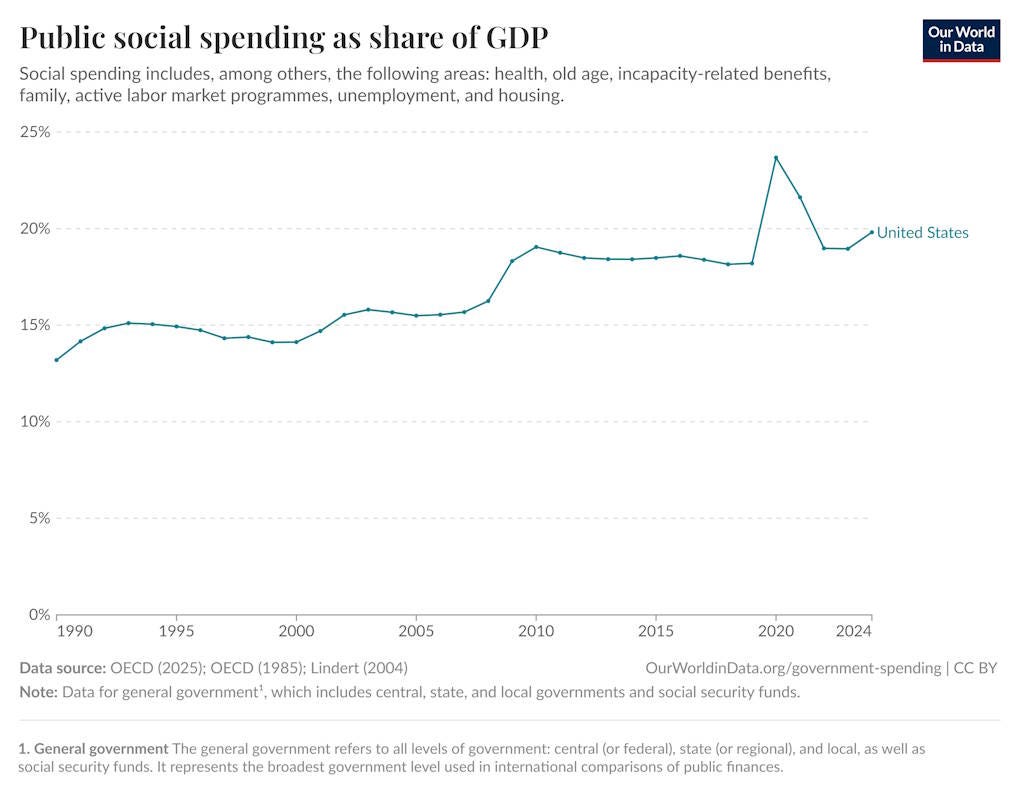

In my youth I believed what my parents taught me to believe — that America was a place of deep inequality, with millions condemned to grinding poverty that could only be solved if we had the will to build a real welfare state. And was I wrong? Beginning in the 1990s, America became a more redistributive, generous nation, under both Democratic and Republican presidencies:

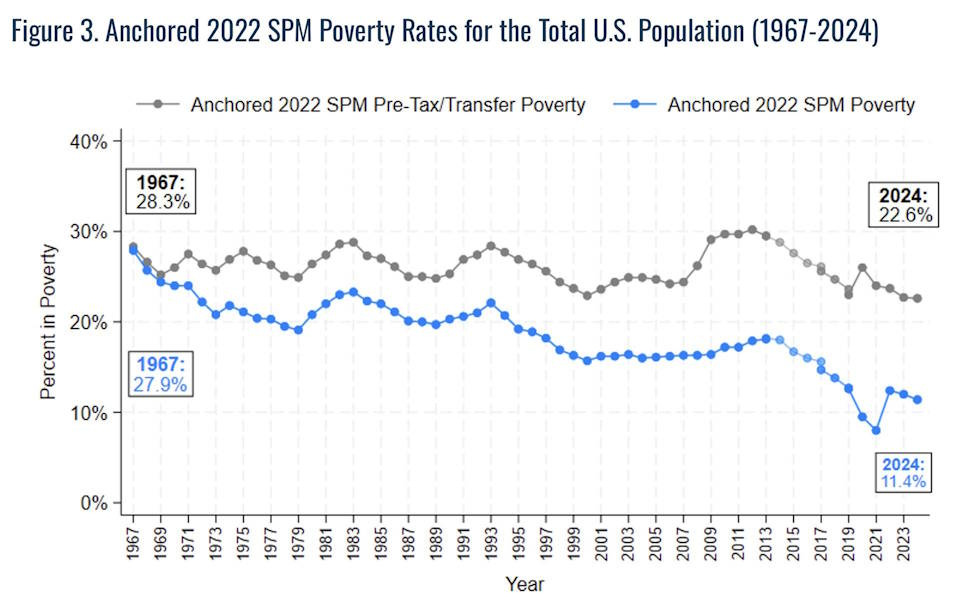

That vague dream of 1980s liberalism became the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Child Tax Credit, the expansion of SNAP and Section 8 and Medicaid and Medicare — a Second Great Society. And thanks to my nation’s turn toward generosity, the rate of after-tax poverty fell:

I don’t yet know for sure if this was the right thing to do — perhaps the bolstering of America’s welfare state came only at the cost of ballooning public debt and withered military preparedness that will eventually come back to haunt us in the long run. But as of today, I would not go back. I would not force millions of Americans to return to the grinding, desperate poverty they suffered in 1985.

The same can be said of so many other liberal dreams of my youth. We dreamed that one day racial discrimination against Black Americans could be consigned to history; by 2010, it was a far less potent force, and by 2023, much of the Black-White employment gap had vanished. We dreamed that one day gay Americans would have their love recognized and honored by society as equal to love between men and women; by 2015, gay marriage was the law of the land. We dreamed that one day, Americans would not suffer economic ruin from the lack of health insurance; by the 2020s, the uninsured rate fell to 8%. We dreamed of a country where people wouldn’t be thrown in dungeons for smoking marijuana; this, too, eventually became our reality.

None of these victories came without cost, and we will never know the true and final consequences of any of them. And yet I would not give up a single one. When I look back at the long arc of American liberalism since my childhood in the 1980s, I see a record of success that I believe will endure.

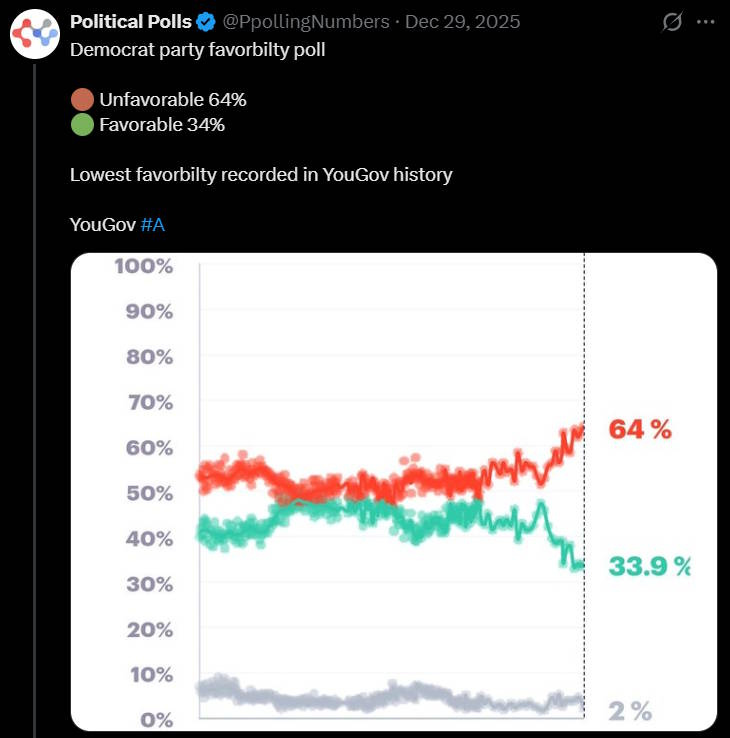

And yet here I stand, in 2026, and America’s long arc of liberalism appears to have bent straight into the dirt. Americans may have soured on Donald Trump, and may hand the Democrats a victory in this year’s midterm elections, but at the same time, they despise the Democratic Party:

Some of this disapproval is from voters on the left, disappointed with their party’s inability to stymie Trump. But much of it is due to the deep disconnect between mainstream American beliefs and the progressive values that now animate the Democratic Party.

As the 2000s turned into the 2010s, I noticed that my fellow liberals had stopped using the word “liberal”, and begun to use “progressive” instead. At first I thought this was a defensive response to taunting from Fox News talk show hosts who had made “liberal” a dirty word. As late as 2013, I saw little difference between the values of Barack Obama and the ideals I had grown up with. But beginning in the mid-2010s, I began to understand that my political “side” had evolved beyond the goals and beliefs of the late 20th century.

Like many liberals of the old school, I watched with concern as the quest to end discrimination against Black Americans evolved into a desire to institutionalize discrimination against White Americans in universities, nonprofits, government agencies, and many corporations — something the liberals of the 1990s swore they would never countenance. I felt uneasy as the desire to expand the welfare state and universalize health care morphed into endless deficit-funded subsidies for overpriced service industries. I watched as the gay rights movement gave way to a trans movement that was deeply out of step with both America’s beliefs and civil rights law.

I watched, too, as “progressive” governance hollowed out the great American metropolises whose revitalization had been one of the quiet triumphs of late 20th century liberalism. A small anecdote illustrates this. Recently, a homeless man attacked and blinded an elderly woman in Seattle. Despite dozens of violent arrests, this man had been allowed to live on the streets of the city, attacking passers-by. A cop on the scene told reporters that “He’s a regular…he usually punches.”

“He usually punches”??? How has progressive governance allowed the people of America’s greatest cities to live like this? After decades of mass incarceration, a loose alliance of progressive DAs, judges, and anti-police protesters shifted blue cities toward far more permissive policies toward property crime, public drug markets, and low-level assaults and harassment. The progressivism that emerged in the 2010s seems to view anarchy as a form of welfare, believing that the best way to help the poor and unfortunate was to allow the worst and most violent among them to terrorize the rest of them without restraint or reprisal.

And at the same time, progressive governance threw billions of dollars at unaccountable and sometimes fraudulent NGOs, allowing state capacity to degrade. Blue states spent lavishly on infrastructure projects that created many jobs but created little actual infrastructure. Environmental mandates in California built less solar and wind power than simply liberalizing land use regulation in Texas. Blue cities failed to build housing, choosing instead to embrace the progressive myth that new construction fuels “gentrification”.

At this point, a litany of progressivism’s missteps reads like a rant. Progressive education policy, which in my youth focused on directing more resources toward the disadvantaged, now focuses on relentlessly dumbing down curricula and testing standards. Progressive scholars in academia have pushed to replace objective truth-seeking with political activism — something none of the liberal professors I knew growing up would have endorsed. Where the liberal culture I grew up with emphasized tolerance, intellectual argument, and broad-minded discourse, progressive culture in the social media age became strident and shrill — an endless cycle of purity spirals and denunciations whose mix of passion and paranoia would have been familiar to Robespierre.

At this point, it would probably save time to ask what modern progressivism gets right. It’s a very short list, and it’s possible that the only answer is “We’re not Donald Trump.” And it’s true — if you absolutely have to choose between voting for an insanely corrupt authoritarian at the head of a hate-filled anti-democratic personality cult and a gaggle of ineffectual ideologues who spend all day canceling each other and spending money they don’t have while their society slowly falls apart around them, you vote for the latter. But I wouldn’t blame you if instead, you opened your favorite LLM and typed “How easy is it to immigrate to Japan?”.

So far I’ve been a bit weaselly and self-exculpatory in my choice of words. There is no bright line between “liberalism” and “progressivism”, and there was no discrete moment when the ideas of the American left flipped from mostly reasonable to mostly unreasonable. The seeds of almost every progressive overreach of the 2010s were there in 1985.

American liberalism’s great historical successes were 1) abolitionism, 2) the New Deal, and 3) the Civil Rights movement. The more modest successes of 1990s liberalism were based on those precedents — a new civil rights movement for gays, an expanded New Deal to fight poverty, and so on. But there came a point when those approaches had succeeded so well that they hit the point of diminishing returns.

The mass incarceration of the 1980s was not actually a “new Jim Crow” — most of the people we locked up had committed serious crimes, and when people stopped committing so many crimes, the rate of incarceration fell. Rising service costs were not amenable to New Deal style solutions. Allowing people with penises to change in women’s locker rooms and giving teenagers puberty blockers upon request turned out not to be something that Americans could bring themselves to regard as a civil rights movement. Telling corporate America that hard work and rationality were part of “white supremacy culture”, or making AI art programs draw Black Nazis, was not the natural extension of the abolition of slavery.

Meanwhile, there were elements of the liberalism I grew up with that had always been deeply problematic, and which were allowed to fester and grow worse in the new century. The anti-development ethos of the 1970s may have once been useful for blocking industrial waste and ugly highways, but it destroyed American state capacity, ruined urban life for the working class by making housing unaffordable, and hollowed out much of the industrial capacity that sustained the working class.

Every social and political movement, if unchecked, tends to take things too far. Ultimately it was the collapse of liberalism’s great rival that allowed it to overgrow its bounds. The self-immolation of Reaganite conservatism in the 2000s — the disastrous Iraq War, the financial crisis and Great Recession, and the moral collapse of conservative Christianity — left liberalism with no real check on its ideological overgrowth. The replacement of the old conservatism with a shambolic rightist cult did little to provide a compelling alternative; instead it just excused progressivism’s worst excesses, by making sure everyone knew that the alternative was even worse.

I’ve spent much of the year since Trump’s election constructing the litany of progressivism’s sins and overreaches. That job is now complete, but the question is: Where does a liberal go from here? Those of us who grew up in the late 20th century liberal dream are now standing on the beach by the hulk of our wrecked ship, staring out to sea and contemplating our next move.

America is now unquestionably in a more conservative era. People crave law and order in their cities. They have soured on woke culture and progressive spending programs. They are groping around for reasons to re-embrace traditional values. This really is Europe after the Congress of Vienna — perhaps not just in the United States, but across much of the world.

But who will build that conservative era, and what form will it take? The many fractures within Trump’s coalition suggest that what he has built will not last; when his singular personal charisma is gone, a gaggle of white supremacists, elitist rich people, conspiracy theorists, and traditional conservatives will fight to claim the mantle of successor. Some disillusioned liberals will be tempted to ditch the Democrats and go over to the other side, throwing their hat in that ring and trying to bring sanity to the Republicans instead.

That would be an easy move. Like the “neocons” who abandoned the 1970s left for the GOP, or the “liberaltarians” who fled the right after the coming of Trump, just say: “I didn’t leave my party; my party left me.” Learn to speak the right-wing lingo, toss out a little red meat to the MAGA base, put on a red hat, and then start pushing the policy substance back toward an updated 21st-century version of Reaganism — race-blind meritocracy, deregulation, Cold War 2 foreign policy, and so on.

This is the path that some progressives, eager to denounce me, have long expected me to take. And if some liberals want to take this route, I won’t condemn them for it. A democracy can only thrive if it has two sane political parties, and the GOP needs a dose of sanity even more desperately than the Dems.

But no. That way isn’t for me. The project of making America sane again is a good and important one, but I’m not going to spend the rest of my political life as a pure pragmatist. The liberal ideals I grew up with still have power, and I still believe in them, even if the progressive movement stopped navigating toward those ideals a while ago.

Progressive “anti-racism” may have become the mirror image of the very thing it despised, but does that mean that the idea of a society free from racial division and “supremacist” movements is a bad one? Of course not. With the internet and modern air travel, diversity will only increase as time goes on — even if nativist backlashes temporarily close the borders, they will reopen. The whole world will need to see what a real post-racial society looks like, and even after all we’ve been through, the United States of America is uniquely well-positioned to create it.

Meanwhile, the project of creating economic security and abundance for the vast bulk of humanity is very far from finished. The 20th century taught us that while business is the engine of prosperity, simply throwing up our hands and leaving everything to the market will let far too many people fall through the cracks.

A clean and livable environment. Respect for free expression. Democracy and political inclusion. A tolerant society that lets people pursue their private desires. These are all not just good ideas, but necessary ones if humanity is to have the kind of future most people will want to live in. And whatever sort of creature is bubbling into existence on the political right, it’s unlikely to give people most of these things — no matter how many pragmatists manage to grab its reins.

And if you squint hard enough, you can start to see conditions becoming a bit more favorable to liberalism. Crime is falling again, and fast. Intermarriage is still on the rise. Young people are tempering their use of social media. People in places like Iran are still trying to throw off their chains, while autocratic regimes like Putin’s Russia are making plenty of mistakes. Any new liberal project will probably be forced to endure years of retrenchment and soul-searching, but there are still fundamental forces pushing us toward a more optimistic, empowered, and tolerant society.

So that’s what you do if you’re a French liberal in 1815. You try again. Looking back at history, we see that the project of human freedom and dignity has had plenty of low points, but that so far it has always recovered. Even if you’re old, you pick yourself up and move onward. Even if you’ve made mistakes and supported one or two bad ideas for a while, you get back on track and learn from your errors. Even if you don’t know exactly where liberalism goes from here, you sit down and you think and you read and you talk to smart people until you figure out a new direction. You try again. And if that doesn’t work, you try again, and again, until you die, and someone else sees how much you tried, and learns from your mistakes, and then they try again.

This climb is long. We have taken some dead-end paths, but the summit is still there, beckoning. We are not done.

Thanks so much for this essay, Noah - it is a tonic for a tired and frustrated mind.

Noah Smith 2028 :-)

At a minimum, this article should form the basis for a rational Democratic platform in 2028