The Bluesky-ization of the American left

Progressives discovered a seemingly invincible weapon. One day it stopped working.

I remember walking through a bookstore in college and seeing an issue of Foreign Affairs with the headline “The Palestinian H-bomb”. I was curious, so I picked it up off the rack and gave it a quick read. The article — written during the days of the Second Intifada — argued that there was no practical way to stop suicide bombers, so as long as the Palestinians were able to keep recruiting a steady stream of people willing to give up their lives to take out a few Israelis, there was really no way for Israel to stop them.

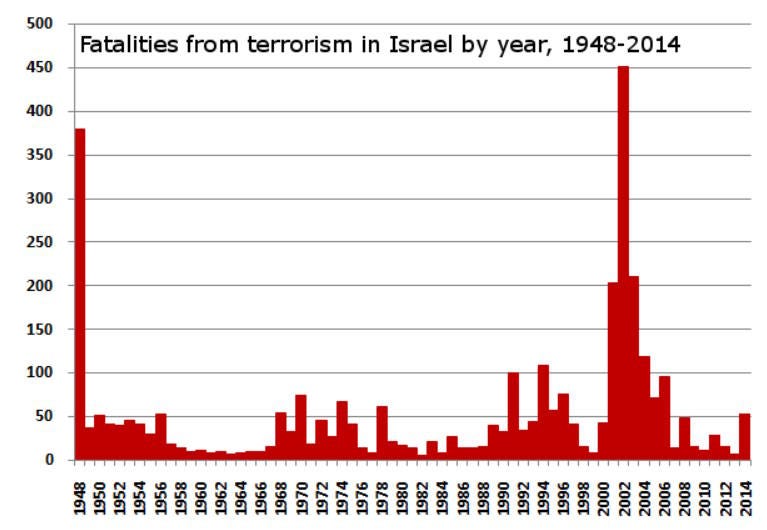

It sounded plausible, and I recall being pretty convinced of the thesis at the time. But it turned out to be wrong. Just a few years after that article was written, suicide terror in Israel subsided to a low level:

What happened? Palestinian recruitment for suicide terror might have flagged, but from what I’ve read, the main reason was that Israel built a big fence around the West Bank and implemented a bunch of other security measures that made it very difficult for suicide bombers to get through. What looked for a while like an invincible weapon turned out to just be another temporary advantage.

I think about this when I think about cancel culture.

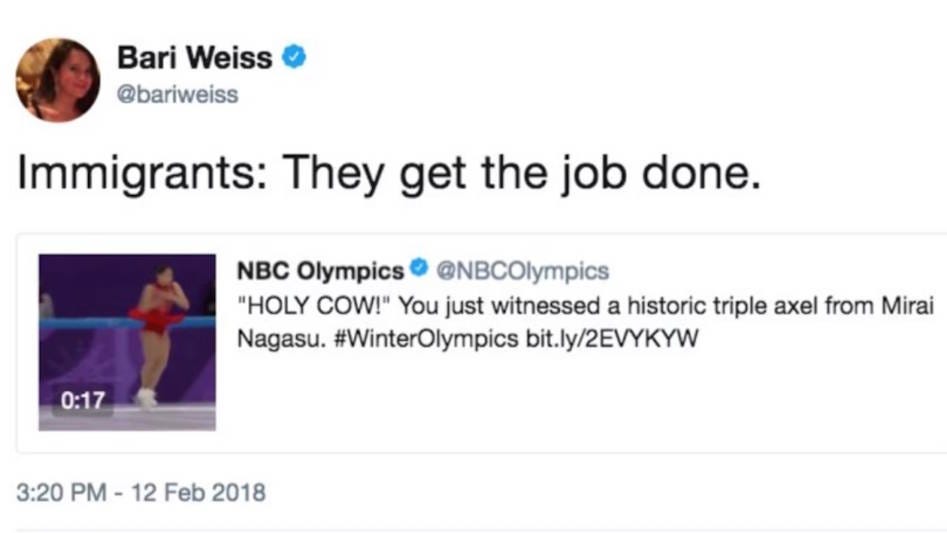

Back in 2018, Bari Weiss got dogpiled on Twitter for an anodyne liberal tweet. Weiss congratulated Olympic skater Mirai Nagasu on pulling off a difficult move, quoting a line from the musical Hamilton about immigrants being great:

Weiss was viciously attacked for this tweet by thousands of people who called her racist over the course of several days. Why? Because Mirai Nagasu isn’t actually an immigrant — she was born in the U.S. According to Weiss’ many attackers, Weiss’ statement implied that nonwhite people are perpetual foreigners.

That was, of course, complete hogwash. Nagasu’s parents are immigrants; the use of the term “second-generation immigrants” to describe the children of immigrants is utterly standard terminology in academic sociology. And by quoting a line from Hamilton in praise of a second-generation immigrant athlete competing on behalf of the U.S., Weiss was clearly advocating in favor of (nonwhite) immigration as something that makes America stronger — a very standard liberal viewpoint.

Whether this particular pile-on had long-term negative consequences for Weiss’ life isn’t clear, but she encountered an increasingly hostile climate at the New York Times, the paper where she worked, and eventually was forced to quit. It would have been reasonable for people observing that pile-on — and similar attacks directed at Weiss over the years — to conclude that speaking up is dangerous and that Twitter mobs hold a lot of real power.

The perception that cancel culture was the progressive H-bomb — an invincible weapon that could be fired any time at anyone who didn’t conform perfectly to a set of progressive mores that had only emerged a few years ago — reshaped much of American society in the 2010s. Every organization in the country, from knitting circles to romance novelist associations to sci-fi conventions, had its internal hierarchy disrupted by the fear that disgruntled or opportunistic subordinates would take their grievances online and summon the dreaded cancel-mob against their superiors.

Why was cancel culture both so powerful and so popular for those few years? The most obvious reason is that it worked. If you were a progressive in 2018 who really believed that calling a second-generation American an “immigrant” was racist, then you could often effectively strike at that person by raising a hue and cry about them on Twitter. Companies were afraid of boycotts, of course. But beyond that, the Gen Xers who ran those companies came from an age when having a thousand people yelling in your face meant that you were in grave danger; corporate managers would often cave out of pure fear of online negativity.

Another reason was that cancel culture was a quick route to online clout. As Eugene Wei wrote in his famous blog post “Status as a Service (StaaS)”, social media offers most people the opportunity to get much more social status than they have any hope of getting in their daily lives, if they happen to get lucky and go viral and become an influencer.

But to get that clout, you have to stand out. Attacking the same old progressive targets — Donald Trump, Republican senators, conservative influencers — is a low-yield activity, because the field is too competitive. Everyone attacks those people. But finding more novel targets for mob attack — like an NYT writer who calls a second-generation American an “immigrant” — can be a high-yield activity. It’s basically outrage entrepreneurship.

Of course, this means that there was an incentive for progressive purity spirals and tent-shrinking. If you’re a progressive looking for new people to denounce, the most tempting targets are probably center-left liberals who have heretofore been safe from cancellation. Hating Donald Trump is old news. But hating Matt Yglesias? That could get you some real attention!

And so the ranks of the online cancel-mobs were probably also swollen by people who participated in the mobs out of fear that if they didn’t, they too would be canceled. This gave rise to a phenomenon I call ponzi screaming — berating the person immediately to your right on the political spectrum, out of fear that if you don’t berate them, people further to your left will berate you. You have people like the progressive online shouter and failed Congressional candidate Will Stancil berating Nate Silver even as he gets frequently dogpiled and berated by leftists.

Between outrage entrepreneurship, purity contests, and ponzi screaming, late-2010s progressive cancel culture started to look like a farcical imitation of the French Terror or the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The stakes were obviously much lower — losing your job is a lot less bad than losing your head — but many of the social dynamics and behavior patterns were recognizably similar.

Except that just like with “the Palestinian H-bomb,” the frightened public vastly overestimated the power of cancel culture. Bari Weiss went on to start The Free Press, a very successful Substack publication that often flouts the same progressive norms that forced Weiss out at the NYT. Now, CBS News is reportedly in talks to buy The Free Press and hire Weiss for a major editorial or executive role at the network.

Progressive cancel culture turned out not to be invincible after all — it was a temporary culture-war advantage that was driven by one group’s early adoption and intensive use of a new technology. The disruption to the lives of people who got canceled was usually (though not always) short-lived. Over time, companies learned that progressive anger was transient and distractable, and that boycotts weren’t going to materialize; after realizing this, they mostly stopped firing people who got dogpiled on Twitter.

Today, if you were to tweet what Weiss tweeted about Mirai Nagasu in 2018, you’d be more likely to get attacked by the anti-immigrant right than by the woke left. And corporate brands are far more likely to be boycotted by the organized right than by the distractable, diffuse left.

The threat of progressive cancel culture in America has been defused.

Part of that, of course, is because of a general conservative shift in American politics since 2021. And part of it is because Elon Musk bought Twitter and turned it into X, causing some progressives to abandon the platform. Many of those progressives went to a similar platform called Bluesky.

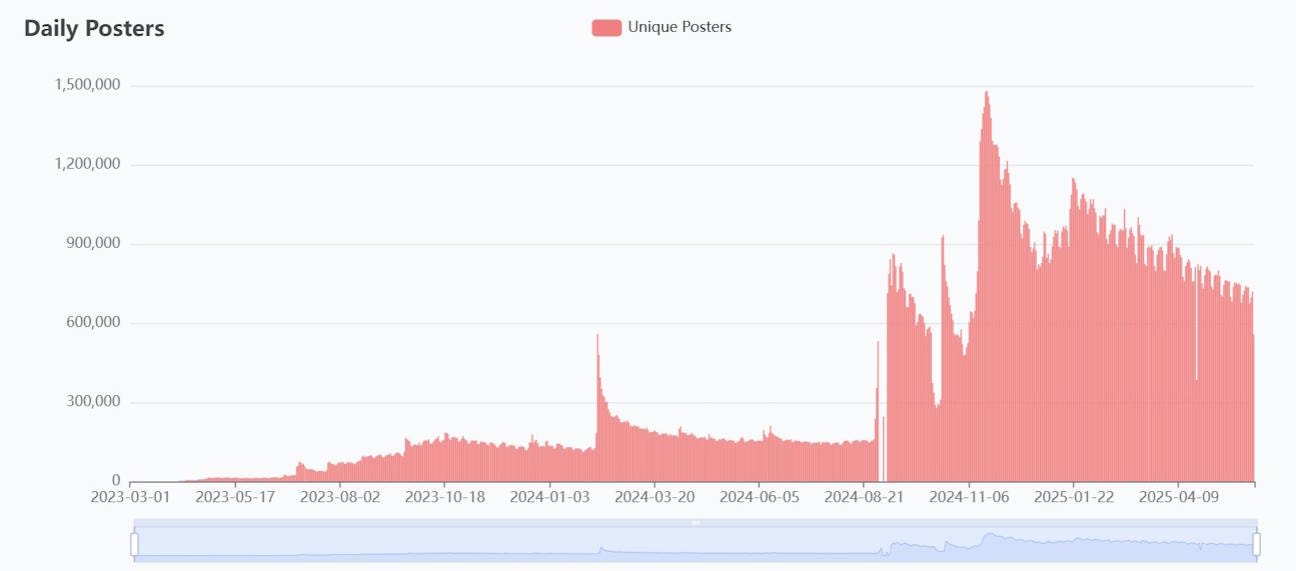

Like right-wing platforms such as Gab, Parler, and Truth Social, Bluesky’s reach is limited. Its usage rates remain far, far below those of X, and a bump of new users following Trump’s election is slowly fading:

Practically all the important progressives — academics, commentators, activists, politicians — are on Bluesky, talking to a much smaller audience than they used to have on Twitter. But what they say just doesn’t seem to matter at all. “They’re dragging your ass on Bluesky” is a statement that strikes fear into the heart of practically no one. A mob denouncing you as transphobic, racist, misogynist, etc. on Bluesky will have essentially no chance of negatively impacting your career.

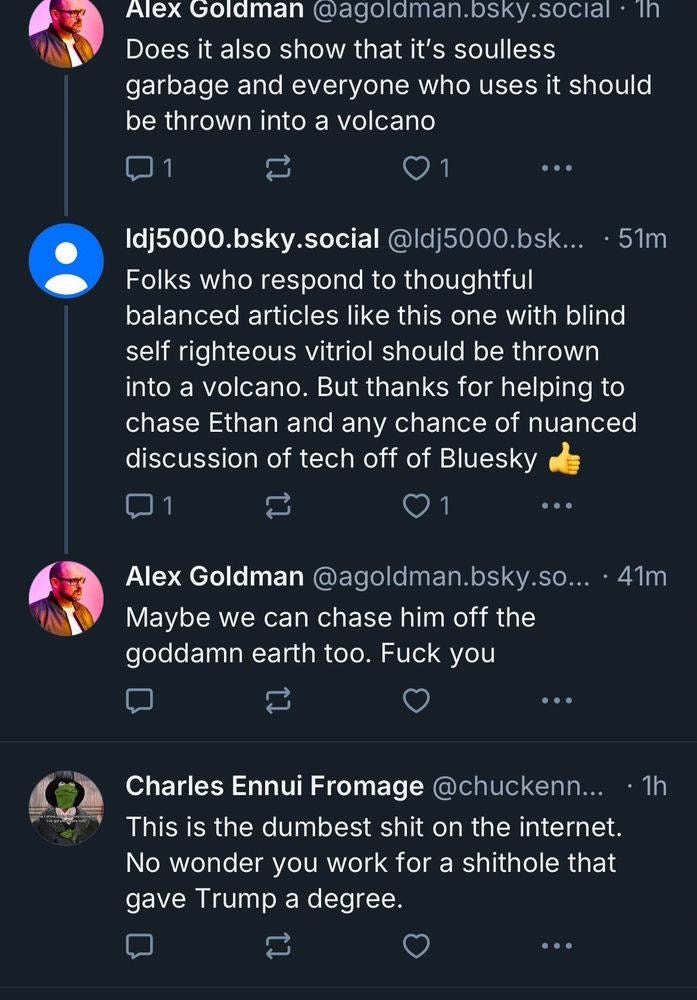

And yet the progressives on Bluesky have retained all the habits of speech, thought, and behavior that characterized the high cancel-culture era of the late 2010s. For most of my life, liberals were known as the nice guys of American politics. But log on to Bluesky, and it’s all just stuff like this:

(This was a response by a journalist to a professor who shared a paper about AI.)

Nate Silver recently wrote a post about the prevalence of this attitude and style of communication on Bluesky:

Some excerpts:

A healthy political movement, you’d think, would welcome people who agree with them on 70 percent of issues, particularly if it sees Trump as an existential threat to democracy and wants a broad coalition against him. Blueskyists do literally almost the exact opposite: their biggest enemies are people on the center-left like me and Yglesias and Ezra Klein. Or center-left media institutions like the New York Times, which are often viewed as more problematic than Fox News…

And sometimes, Blueskyists even make violent threats toward people who disagree with them. For instance, the journalist Billy Binion says he recently “logged onto Bluesky to find thousands of people screaming at me, many of whom were telling me to kill myself” after having posted that “billionaires should exist”.

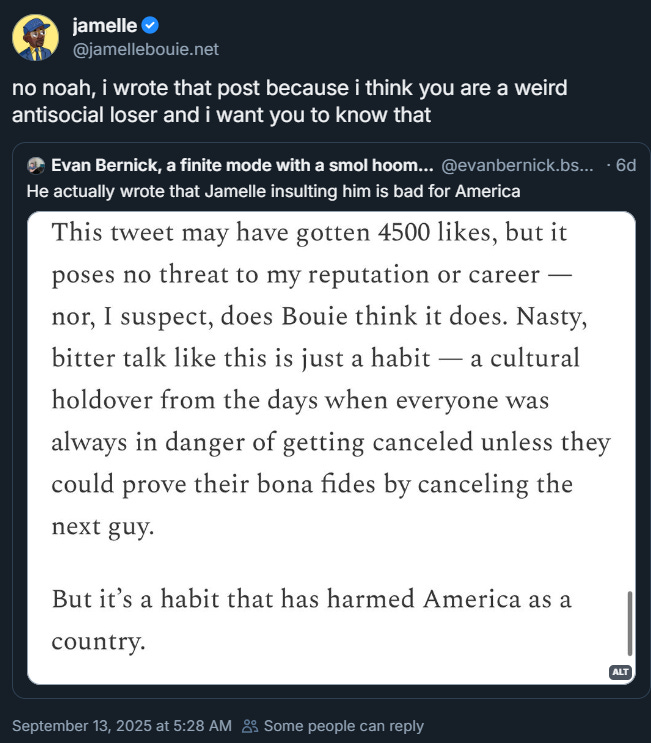

Whenever I read a criticism of my writing on Bluesky, it seems to be insubstantial and denunciatory, like this casual insult from New York Times writer Jamelle Bouie:

This tweet may have gotten 4500 likes, but it poses no threat to my reputation or career — nor, I suspect, does Bouie think it does. Nasty, bitter talk like this is just a habit — a cultural holdover from the days when everyone was always in danger of getting canceled unless they could prove their bona fides by canceling the next guy.

But it’s a habit that has harmed America as a country.

Progressive culture’s substitution of nastiness for persuasion and argument has robbed America of the incisive commentary of which intelligent progressives would otherwise be capable. Progressives got addicted to the power of cancel culture — their seemingly invincible H-bomb — and when it stopped working they just didn’t know what else to do, because they had forgotten everything they used to do in the time before Twitter. Here’s what I wrote in a recent thread:

There was this big idea that social media was this infinitely powerful tool that allowed a small # of progressives to shame a huge number of Americans into accepting their values…But progressives got addicted to that seemingly infinite power. They forgot everything else. They forgot how to persuade. They forgot how to organize. They forgot how to compromise. They thought the only tool they would ever need again was heckling and shunning on social media.

Undoubtedly, the Bluesky progressives think that they’re just socially shunning people — exercising the age-old power of social ostracism to show the door to people whose opinions are beyond the pale of polite society. But the cultural spaces that progressives still dominate are shrinking; very few people are likely to think of Bluesky as anything resembling “polite society”. Instead of ostracizing the people they hate, Bluesky’s progressives are only isolating themselves.

Megan McArdle wrote that by secluding themselves within the Bluesky enclave, America’s progressives have made themselves less relevant:

[Bluesky’s nastiness] makes it hard for the platform to build a large enough userbase for the company to become financially self-sustaining, or for liberals to amass the influence they wielded on old Twitter. There, they accumulated power by shaping the contours of a conversation that included a lot of non-progressives. On Bluesky, they’re mostly talking among themselves.

Within this little hothouse world that American progressives have created for themselves, there’s not much to do except try to cancel each other. Meanwhile, the broader country is moving on without them, and not in a good direction. One of the reasons opposition to Donald Trump’s executive overreach and harmful policies has been weak in his second term in office is that progressive writers are hanging out on Bluesky trying (and failing) to cancel Matt Yglesias and Nate Silver.

Progressives need to snap out of it. They need to realize that the late 2010s were a very special time that will not be repeated again in our lifetime, and that they need to go back to the older tools of persuasion, compromise, organization, and effective governance, instead of sitting around saying nasty things about each other until the country collapses around our ears.

Update: On Bluesky, Jamelle Bouie responds to this essay:

I have anon accounts at Twitter, Bluesky, Truth Social, reddit and I can't say that there is any serious discussion on any of the main channels or topics on any of the sites.

I look at the replies that Mark Cuban gets on Bluesky for trying to hold real conversations and its basically everyone just screaming into his face telling him he is the worst person ever for being a billionaire (regardless of topic posted)

Twitter is basically Elon's playground now for his "free speech" which restricts views that might be unfavorable to his brand, companies and politics.

Truth social is basically a cult member zone for everything MAGA related. Every reply and post that I have seen on the platform is basically propaganda for the administration.

Reddits main sub-reddits idea of "discussions" is to post favorable links for progressive websites (that nobody clicks on) and every comment is basically to call everyone who they disagree with a nazi or a facist.

For all the talk that people say they use social media for (expand their knowledge, connect with other people etc) it seems to just radicalize people based on whatever platform you use.

And the amount of bots and foreign agents trying to stir things up just makes most places awful to be in.

To be honest, the less time spent on social media, the better I feel. And I question every day why don't I just delete all social media and read news/blogs instead.

Youtube would probably the hardest to quit though.

Excellent piece, Noah. I think about this a lot. I don't participate in SM but I experienced similar firsthand as a professor. After teaching for a decade the same topics in the same way, I had a small group of students who registered formal complaints about me because "their voices weren't being heard" in my class discussions (this was around 2018). Fortunately, my level headed superiors didn't make anything of it but it was a wake-up call that I now had to walk on eggshells in my lectures. I teach decidedly non-political topics and rarely to never stray into them. This re-flared around the Hamas attack a few years back and that was complex where students wanted to stand up in front of my class to make statements (I teach in a business school). It was very difficult to navigate.

Like you, I despise that period mostly for its shutdown of any discourse around disagreements. The hard left were really the pioneers here as you note. I wish they had a tiny bit of self reflection now that we see how they enabled the right to do the same.