Western democracies are actually pretty good at war

The authoritarian advantage is hype. But China is the real deal.

“They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too.” — William T. Sherman

I am not a military analyst or expert. Usually I look at the world through the lens of economics, which I actually have some training in. But if you want to get a good holistic picture of the world, you need to understand at least a little bit about war and conflict. I think most pundits intuitively understand this, which is why you see them weighing in on things like the usefulness of military aid to Ukraine, or the cost-effectiveness of the F-35, or the need to establish military deterrence against China. And so I do the same, while being careful to remember that I’m not any kind of expert in the field.

One of the most persistent and annoying tropes I see, in discussions about war, is the idea that autocracies are inherently tough and martial, and that democracies — especially Western democracies — are irresolute, decadent, flaccid, and generally not very good at fighting. You see this when rightists praise Russian military ads where soldiers do a bunch of push-ups, and decry the state of America’s “they/them army” in comparison. You can see it when leftists declare that America loses every war it fights (which is obviously false). The idea is ingrained in our deep history — Thucydides lamented that “a democracy is incapable of empire”, and plenty of modern people will cite autocratic Sparta’s victory over democratic Athens in the Peloponnesian War.1

In fact, if you just looked at the results of the last two decades, you might be forgiven for buying the authoritarian hype. America was pushed out of Afghanistan, and its proxies quickly collapsed under the Taliban assault. Most people also say the U.S. lost the Iraq War.2 Democratic Armenia quickly lost a war to autocratic Azerbaijan in 2020, Israel broke its teeth on Hezbollah in 2006, Russia smashed Georgia easily in 2008, and Russia easily took Crimea from Ukraine in 2014. Since the turn of the century, military victories for Western democracies were few and far between.

But over the past three years, the tide seems to have turned once more. Ukraine, astonishing the entire world, fought mighty Russia — a country four times its size and with far higher GDP per capita — to a standstill. In 2024, Israel smashed Hezbollah within just a few weeks; the Iranian-backed militia retreated from the border and its authority is now being replaced by the elected Lebanese government.

And now there’s the war between Israel and Iran. The war just started; all of us are still just monitoring the situation. It seems hard to think that Israel can prevail in a protracted confrontation with a nation with nine times its population and more than three times its GDP (PPP).3 But as of right now, the tiny David is smacking around the big Goliath. Israel quickly established air supremacy over much of Iran itself, despite the huge distances between the countries, using a mix of traditional aircraft and drones:

Just four days into its ferocious air campaign, Israel appears to have gained a decisive edge in its escalating conflict with Iran: aerial supremacy over Iran…The Israeli military said Monday that it can now fly over the country's capital, Tehran, without facing major resistance after crippling Iran’s air defenses in recent strikes, enabling Israel to hit an expanding range of targets with relative ease…Such control over Iran’s skies, military analysts say, is not just a tactical advantage—it’s a strategic turning point…Israel has carried out one of the most intense and far-reaching air operations in its history, targeting nuclear sites, missile launchers, airports, and senior figures in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps…

For Israel to claim this over Iran just days after the strikes began is an impressive military accomplishment, says Michael Knights, the Bernstein Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute who specializes in Middle Eastern security. “It's exceptional to get this level of freedom. I’m quite surprised that they’ve managed it,” he says[.]

Israel has destroyed Iran’s best fighter jets on the ground. Iran has been reduced to firing off ballistic missiles into Israeli cities in retaliation. But the strikes, while visually impressive, have not been very deadly (the Israelis all have bomb shelters). And the Israelis are managing to quickly degrade Iran’s missile capabilities:

Iran is firing fewer missiles at Israel each day after Israel secured dominance over Iranian skies, enabling it to destroy launchers and take out missiles before they even leave the ground…Israel said on Sunday that it had created an air corridor to Tehran. By Monday, it said its air force had complete control over the skies of Tehran…This aerial control is proving crucial. Iran fired some 200 missiles in four barrages in its first round of attacks against Israel on Friday and Saturday. But between Tuesday and Wednesday, Iran fired 60 missiles at Israel over eight different waves of strikes, at times sending fewer than a dozen at a time…Israel’s aircraft and other security forces have destroyed 120 missile launchers[.]

Israel hasn’t yet decapitated the Iranian regime, but it’s killing lots of key figures. This is a pretty stunningly bad performance for Iran — a country that is sometimes touted as a key member of a new Axis with Russia and China — against a country with the population and land area of New Jersey.

Israel isn’t quite Western — more than half of its population is descended from Middle Easterners — and its Prime Minister Netanyahu has shown some authoritarian tendencies. Nor is Israel a particularly liberal state, at least as far as its treatment of the Palestinians goes. But it’s a heck of a lot closer to being a “Western democracy” than Iran is.

Rumors of the weakness and decay of the West, and of the inferiority of democracies in the face of autocratic power, seem to have been at least somewhat exaggerated. What’s going on? In fact, the first two decades of the 21st century may have been an aberration; democracies actually do tend to win wars more often than they lose.

Why do democracies win more wars?

A quick glance at history will disabuse any neutral observer of the notion that Western-style democracies are militarily weak. Consider how France held off attacks by all of Europe for decades after its revolution, or how the Anglo-American side won both World Wars, or how Israel beat a bunch of its neighbors in a series of wars, etc. Hitler and Mussolini both loudly proclaimed that democracies were weak and decadent, yet it was they who ended up in history’s graveyard.

In fact, there’s pretty robust evidence that democracies — at least, as we currently identify them — tend to win wars more often than autocracies do. Dobransky (2014) finds that “democracies win the large majority (84%) of wars that they are involved in.” Reiter and Stam (2014) find the same:

Analyzing all interstate wars from 1816 to 1982 with a multivariate probit model, we find that democratic initiators are significantly more likely to win wars; democratic targets are also more likely to win, though the relationship is not as strong.

Mathematically, this must mean that democracies tend to defeat autocracies when the two fight, because if two autocracies or two democracies fight each other, a win for one nets out to a loss for the other.

Political scientists have any number of theories to explain why this happens. One obvious possibility is that democratic countries fight fewer wars in the first place, and only tend to fight when they have a good chance of winning. This is David Lake’s theory, which he calls the “powerful pacifists” theory.

Reiter and Stam, who have a book called Democracies at War, agree with Lake that autocracies tend to start riskier wars than democracies do. But they have very different reasons for thinking this. Lake thinks dictators tend to start wars for resources, because running a dictatorship is very costly. Reiter and Stam, on the other hand, think that dictators start wars because they’re more secure in their power, and thus are less afraid of the negative consequences from a war going badly.

Honestly, I’m not very convinced by either of these explanations. Yes, there are some wars over economic resources — Saddam Hussein invading Iran to try to capture its oil fields in 1980 comes to mind. But I don’t think most wars are mostly over treasure in the modern age. The World Wars were mostly over ideology and perceived threats rather than imperial conquests. Putin didn’t invade Ukraine for money, and money has nothing to do with why Iran has been sending proxies to attack Israel for decades. Even when wars do have an economic component, the benefit of winning rarely justifies the cost of fighting in the first place — witness America’s inability to extract significant value from the oil fields of Iraq.

Likewise, I think it’s unlikely that dictators are less afraid of losing wars. Yes, they may be better positioned to cling to power in the event of a loss, while democratic leaders will be promptly voted out of office. But the lower probability of an autocrat being tossed out of power comes with a much greater severity. A U.S. president who loses a war might be voted out of office; when Mussolini lost a war, he ended up hanging from a gas station, riddled with bullets. So honestly, I’d be more cautious if I were a dictator.

I think there’s a much more obvious reason why democracies choose their wars more carefully. In general, the people who actually have to go fight a war tend to like war less than the leaders who simply order their armies forward from the safety of their bunkers. So democracies, where the people are more in control, tend to be pacifist; they only tend to fight either when they have a good chance of winning, or when their back is to the wall and they can’t afford to lose. When they are finally moved to fight, the stakes tend to be high, the people tend to be united and motivated, and the cause tends to be one that draws in lots of allies.

Economic factors probably play a role too. Lake thinks democracies have more economic resources to devote to war, because he believes they tend to spend more money on building up their economies, while autocracies tend to be extractive.4 This makes sense sometimes — think of how America outproduced the Axis in World War 2. On the margin I think it makes a difference, but I’m skeptical of how much it can explain overall, because population size often differs so much between combatants that per capita GDP differences become less important. Consider Israel versus Iran — at PPP, Iran’s economy is much larger, because it’s a much larger country, even though it’s poorer.

There’s another economic factor at work, which is technological advancement; having a higher per capita GDP generally means having better technology, which can be used for weaponry. Israel has a smaller economy than Iran, but because it has a richer, more technologically advanced economy, it can do a lot fancier stuff — with drones, aircraft, missile defense, precision weaponry, hacking, digital intelligence gathering, and so on.

As for whether democracy actually makes a country richer and more technologically advanced, that’s a topic of ongoing debate. Some people think democracy is good for growth; others think that as countries get richer, their citizenry starts to demand a transition to democracy. Other people think it’s a historical accident. But whatever it is, democracies do statistically tend to be richer than autocracies, and being rich helps in war.

Actually, you don’t always need to be richer in order to have superior technology. Ukraine is much poorer than Russia on a per capita basis, but it has a lot of great computer programmers and engineers — it has repeatedly innovated in drone warfare during the current war, forcing Russia to scramble to keep up.

Reiter and Stam also argue that the way dictatorships make decisions is not very conducive to effective war-fighting. In an op-ed written shortly after the start of the Ukraine War, they explain:

[L]ike most dictators, Putin probably has some concerns about being overthrown by his own military. Dictators guard against this potential threat by centralizing military command authority and reducing the ability of lower-level commanders to take the initiative in battle…

These moves may reduce an army’s ability to seize power in a crisis — but also undercut the military’s ability to defeat foreign foes…Putin’s army today demonstrates the calcification and rigidity of a dictatorship. He appears unwilling to delegate decision-making autonomy to lower-level commanders, reducing military effectiveness…

[D]ictators often surround themselves with yes-men and political cronies, who deceive or remain silent rather than tell the unvarnished truth…In contrast, democratic leaders are more likely to have the benefit of robust debate inside and outside government…Every indication is that the Russian president is isolated and getting poor information…Putin’s generals and intelligence chief reportedly refused to tell him the truth before the war: that years of Russian military reform had not made substantial progress, instead producing a “Potemkin military.”

That makes lots of sense. To this I’d add the simple fact that if your country happens to have a dictator, he’s probably simply more politically capable of micromanaging — and mismanaging — the military, whether or not he’s doing it because he’s afraid of a coup.

So I’d say the three main hypotheses for why democracies tend to win more wars are:

Democracies fight less, so they tend to only fight more winnable wars

Democracies have better economies and technology

Autocracies have structural tendencies toward military mismanagement and poor information flow

Most of these make sense in explaining Ukraine’s success in holding off Russia. Ukraine didn’t want to fight this war, or any war; they only fought because their backs were to the wall and the survival of their nation was at stake. They have proven to be technologically innovative and resourceful, even with their much smaller economy. And their decision-making has been consistently better and quicker than that of the plodding Russians.

These factors also help explain Israel’s success against Iran. Israel does fight a lot of wars, but that’s because it has a lot of enemies who attack it a lot; other than their slow colonization of the West Bank, Israel has no imperial designs. Iran, in contrast, is constantly meddling in conflicts all around it, supporting proxy armies in Yemen, Libya, Syria, Iraq, and Gaza. With Israel, Iran picked on someone who was able to stand up and punch it in the nose. Israel also has superior technology, better command and control, and a more unified, engaged populace.

China is a different beast entirely

But there’s one other important hypothesis for why democracies have tended to win wars — help from the United States. For about as long as democracy has been around, the U.S. was the world’s mightiest economic and technological power, capable of sending game-changing weaponry anywhere in the world. That didn’t always guarantee victory, obviously — America’s proxies in Vietnam and Afghanistan were so weak that they collapsed even with U.S. supplies. And no country will be successful in war unless it makes plenty of weapons itself — as Ukraine and Israel both do. But it’s undeniable that American assistance has been at least somewhat important for both Ukraine and Israel in their current conflicts.

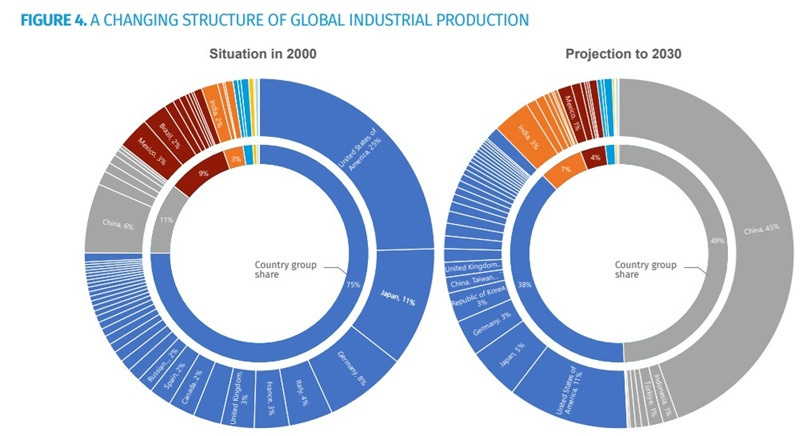

And that’s a big problem right now. Because the U.S. is no longer the world’s leading economic power — at least, not by any metric that would matter in a war. And whatever remains of its technological leadership is quickly vanishing. For the first time since the Industrial Revolution, it’s an autocracy — China — that commands the greatest resources. Even if the U.S. hadn’t allowed its defense-industrial base to wither, China would still manufacture as much as America and all of its democratic allies combined:

As for technology, there are still a few areas where America is ahead, such as leading-edge computer chips and aircraft engines. But in most areas of manufacturing and software, China has caught up or almost caught up, including in AI. And in some crucial areas, like batteries and magnets, America has voluntarily forfeited and isn’t even in the race.

That means that if China does choose to fight America, one big traditional advantage of democracies — economic and technological supremacy — won’t exist. Instead, a best case scenario is that it would be more like World War 1 before the entry of the U.S., where Britain, France, and Russia found themselves evenly matched against a somewhat autocratic but technologically and economically advanced Germany.

Nor is China likely to rush clumsily into war the way Putin did. In the 20th century, China did get involved in some reckless, stupid wars — in Korea in 1950 and Vietnam in 1979, neither of which it won. But since then, China has shown extreme caution. Its leaders definitely seem determined to build up overwhelming power before taking Taiwan or other territories in Asia. If the U.S. has to fight China, it will be at a time and place of their choosing, not ours — and they will likely have most of their people unified behind the effort.

This doesn’t mean the democracies would have no advantage against China. The structural problems of autocracies — poor information flow, over-centralization of power, paranoid infighting — all seem present, as Xi Jinping completes his transformation of Deng Xiaoping’s bureaucratic, technocratic system into something closer to a traditional dictatorship.

Xi has already made a ton of mistakes, many of them related to micromanagement — Zero Covid, Belt and Road, the crackdown on IT in 2021, the real estate bust, “wolf warrior” diplomacy, and so on. It’s likely he would micromanage a war as well. Meanwhile, Xi has been purging his top military officers, many of whom he himself appointed, at a stupendous rate, for reasons unknown.

So if China does fight America, it will have some of the same sorts of disadvantages that Russia has with Putin. But it’s far from clear whether these would be enough to overcome China’s massive manufacturing advantage. Democracy is a lot tougher than people give it credit for, but it’s not magic.

Though note that Sparta itself was promptly defeated by Thebes, which had transitioned to democratic rule several years earlier.

This is clearly false. The U.S. didn’t just overthrow Saddam with ease; it also defeated Sunni and Shia militias alike, and then defeated ISIS. The regime that the U.S. set up in Saddam’s wake is still in control in Iraq, and is still friendly to the U.S. By every conceivable past and present definition of what it means to “win” a war, the U.S. won the Iraq War. However, the victory didn’t benefit the U.S. strategically — it diminished America’s geopolitical standing and broke the global norm of non-aggression that the U.S. had championed since World War 2, paving the way for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. So the Iraq War is a demonstration of the fact that victory in war isn’t always worth fighting the war in the first place. In contrast, the Afghanistan War was a loss for the U.S., but Al Qaeda was effectively destroyed, Osama bin Laden and all other 9/11 planners were captured or killed, and the Taliban were neutralized as a strategic threat.

PPP is probably better than market exchange rates when comparing economies for military purposes, since most military goods — especially soldiers’ salaries and provisions — are produced domestically rather than acquired on world markets. This is especially true for Iran, which is under international sanctions.

This is a key implication of Selectorate Theory, which is popular among political scientists.

"For about as long as democracy has been around, the U.S. was the world’s mightiest economic and technological power, capable of sending game-changing weaponry anywhere in the world. "

Even if we completely ignore the democracies that pre-date the US, the US only surpassed the British Empire economically during WWI, or 110 years ago.

I really appreciated this disclaimer in the beginning, Noah: "I am not a military analyst or expert. Usually I look at the world through the lens of economics, which I actually have some training in. But if you want to get a good holistic picture of the world, you need to understand at least a little bit about war and conflict... And so I do the same, while being careful to remember that I’m not any kind of expert in the field."

But--and I really say this from love and as a true fan of your work--I wish you would also show a little more epistemological humility about political, political economy, and culture topics from European and other Western, developed countries. Because even if you are absolutely a credible expert and astute voice on American (and East Asian) economics and political economy, I do think you can fall for the groupthink and a Thomas Friedman-esque generalizer mode when you're giving commentary about events on the other side of the Atlantic, in ways that neglect the crucial nuance and on-the-ground empiricism that you otherwise give in domains you're more directly exposed to on a regular basis (like Japan). It's far from just you who does this, but I think you're better than this and rare among popularizing commentators for having rigor and humility as well as verve, style, and a clear POV.