Uh, guys, we really should think about spending more on defense

That's not a message many people want to hear, but it's true.

The United States is in big trouble militarily. That’s the upshot of a new RAND publication called “Inflection Point”:

[I]t has become increasingly clear that the U.S. defense strategy and posture have become insolvent. The tasks that the nation expects its military forces and other elements of national power to do internationally greatly exceed the means that have become available to accomplish those tasks. Reversing this erosion will call for sustained, coordinated efforts by the United States, its allies, and its key partners[.]

Basically, the report says that the U.S. military’s technological superiority has mostly eroded, and to address that, we need to shift from projecting power to defending against attacks by other powers (i.e. China). RAND then gives a large number of concrete recommendations on how to change the U.S. military in order to do that. But transforming the military costs a lot of money; even if we don’t end up with a bigger military after the shift, getting from here to there will involve a lot of research, design, testing, and equipment purchasing.

But military modernization isn’t the only thing we need to spend money on. We also need to rebuild our defense-industrial base, which has atrophied since the Cold War ended. The Ukraine War has shown just how many missiles and shells get consumed in a modern war. To the U.S.’ surprise and dismay, we’ve found ourselves completely unable to keep up with the needed shell production. We’re ramping up, but only to a modest level, and even that will take years.

Administration officials and politicians on both sides of the aisle agree that the problem is dire. If we can’t even produce enough shells for Ukraine, trying to match Chinese output would be a hopeless endeavor:

[In a war game of a Taiwan invasion], Washington ran out of key munitions in a matter of days…And as a protracted siege ensued, the U.S. was much slower to rebuild, taking years to replace ships as it reckoned with how shriveled its industrial base had become compared to China’s…

The problem has come into sharp relief only in the last few years as Russia invaded Ukraine, leading to a prolonged war that has drained U.S. munitions stockpiles, and China dramatically escalated both its military spending and aggressive rhetoric…

[A] swift response may not be possible, in large part because of how shrunken the U.S. manufacturing base has become since the Cold War. All of a sudden, Washington is reckoning with the fact that so many parts and pieces of munitions, planes, and ships it needs are being manufactured overseas, including in China…Beyond that, skilled labor is sorely lacking…The U.S. has slashed defense workers to a third of what they were in 1985…and seen some 17,000 companies leave the industry[.]

If you want to read about the details of those war games, you can do so at CSIS’ website. It’s frightening stuff.

Nor would shells be the only thing America would need to produce in quantity in case of a conflict with China. A leaked slide from a recent Navy presentation shows just how many more ships China can produce than the U.S.:

Nor are these a bunch of little crappy ships that would be overmatched by their mighty American counterparts. New Chinese ships are now considered top of the line, able to match or nearly match American ships in quality while utterly overwhelming them in quantity.

So anyway, if we’re going to be able to match Chinese military power — even in concert with all our friends and allies — we need to spend a lot more on the military. If you say this in public, someone will inevitably reply that “we spend more on our military than the next 10 countries combined”, and call for cutting defense spending in order to fund either social spending or tax cuts, depending on which side of the political aisle they fall. But what does it mean for the U.S. to outspend all other nations when China can build warships at 200 times the rate we can? What does it mean for the U.S. to outspend all other nations if we can’t even keep up enough munitions production to supply Ukraine?

Nothing. Dollars on paper mean nothing; shells and missiles and ships are real things that can be counted. As with health care and housing and train stations and everything else, Americans have deluded themselves into believing that as long as they allocate dollars to something in a spreadsheet, then valuable and useful real stuff is actually getting built. Again and again, that delusion has been shattered when excess costs and interminable delays block the paper dollars from becoming real tangible goods.

So if you say we need to transform the way we spend money on the military — to overhaul the defense procurement process, to weaken the dominance of the five “prime” contractors, to eliminate bottlenecks in the production chain, and to generally fight the excess cost problem that seems to plague every American endeavor, I will say “Yes. Yes we do.” But that doesn’t mean we should do those things as an excuse to cut military spending. In fact, we should do those things AND increase military spending, because upgrading the defense-industrial base will itself cost money in the short run, and because cutting costs is a long and arduous process, and because we need to build a bunch of equipment immediately, and because even in the best-case scenario we are going to need a bigger military than we currently have.

Military preparedness doesn’t mean just hurling ever more taxpayer money into the hungry maw of Raytheon and Lockheed Martin. But no matter how effectively we reform our system, preparing for the conflict that might be coming will be an expensive endeavor.

Fortunately, we can absolutely afford it. Inflation has basically been beaten, so that’s not nearly as big of a concern. And when we look back at our history, we see that in the 1950s and 1960s — the glorious postwar years of rapid and equitable growth and plentiful jobs — we spent far more on our military than we do now.

That historical experience suggests that defense spending is not a simple tradeoff of “guns vs. butter”. Yes, it’s possible for a country to bankrupt itself by spending too much on defense, but in the 50s and 60s we dedicated double the fraction of GDP to the military that we do now, and it didn’t interrupt our prosperity.

Now, “We need to spend more on defense” is a message that doesn’t really tend to resonate well with progressives. Frankly, many seem to be stuck in the 90s, when bumper stickers like this one were common:

That wish, expressed in the heady days of the post-Cold-War “peace dividend” when we were winding down Reagan’s defense buildup, essentially came true in the decades that followed, as social spending vastly outstripped defense:

Meanwhile, right-wingers in Congress have shown themselves perfectly willing to block defense spending in order to advance their culture-war goals.

But even as our political elites attack defense spending or hold it hostage as a bargaining chip, the American public is actually pretty supportive of beefing up the military. This is from an AP-NORC poll back in March:

The other really big chunk of the budget? Defense spending, which is about one-eighth of it. The poll shows more openness to cutting there, but still, only 29 percent of Americans say we’re spending too much, while more — 35 percent — say we’re spending too little.

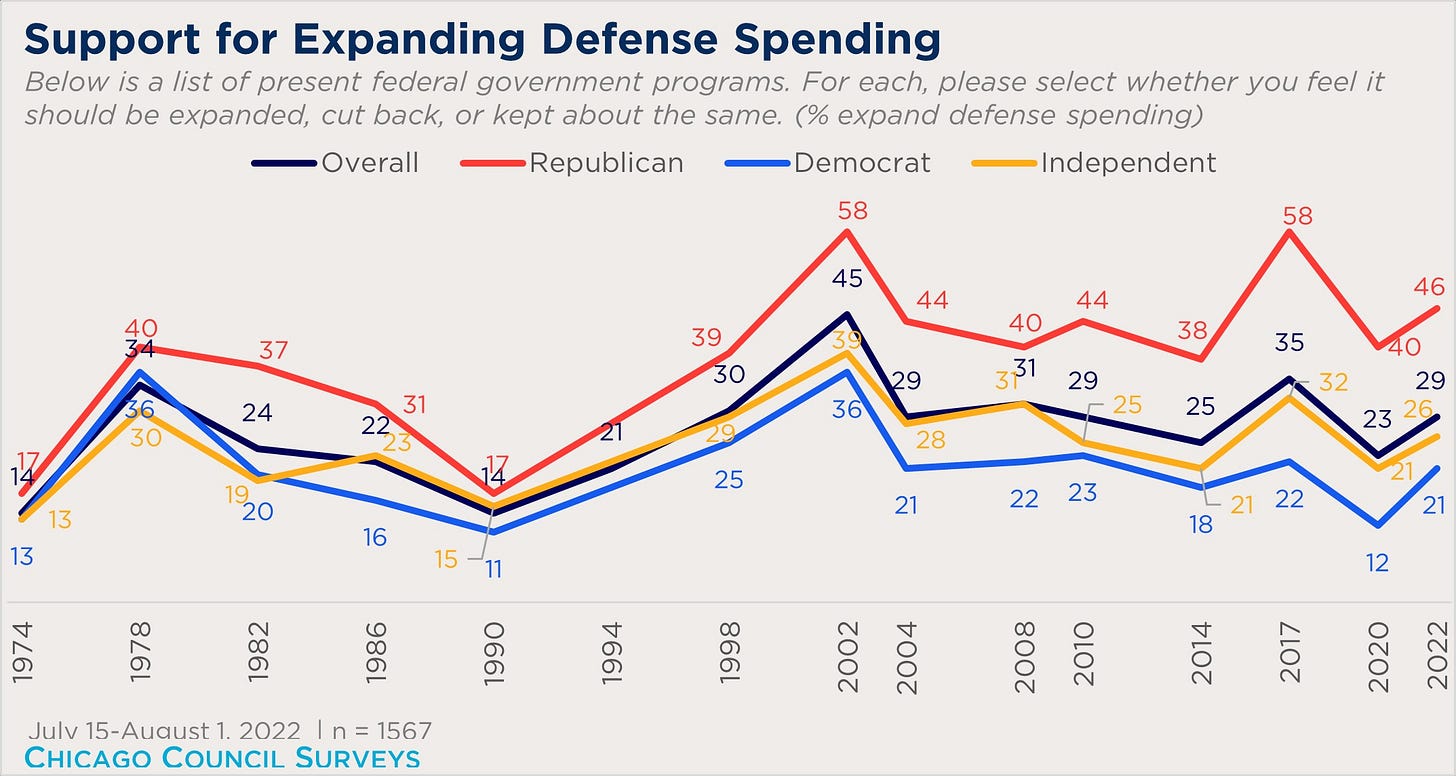

And here’s a Chicago Council on Global Affairs survey from last summer:

That level of support for expanded defense spending isn’t very high in an absolute sense, but it’s notably higher than during Ronald Reagan’s defense buildup in the 80s.

So it doesn’t seem like our leaders will pay a price at the polls for boosting defense spending. As it happens, restoring the defense-industrial base will also create jobs — this shouldn’t be the purpose of military spending, of course, but it would make it a politically safer bet.

Of course, we could simply wait until the balloon goes up and Chinese missiles start raining down on our bases in the Pacific. At that point, support for increased defense spending, military transformation, munitions production, and all the rest will shoot through the roof, as support for war production skyrocketed after Pearl Harbor. But by then there’s a good chance it’ll be too late — in the years that it’ll take us to overhaul our sclerotic system, we’ll have run out of munitions and we’ll be up against a smoothly functioning Chinese manufacturing juggernaut.

I hope this never happens, of course; I think there’s a decent chance it never will. But it’s important to be prepared, and right now, the United States is very much not prepared. In 1941 it was OK to not be prepared, because we had the mightiest industrial base in the world by far, and we could — and did — ramp up over time. In 2023, it’s our rival that has the world’s mightiest industrial base by far, and they can ramp up a lot more and a lot faster than we can.

In the post-Cold War years and the Iraq War years, it made sense to cut defense spending, because that spending either wasn’t needed or was being wasted. But America’s writers and politicians and fashionable intellectual hipsters need to realize that those eras are both over, replaced by a terrifying new age of great-power competition. Right now, trapped in our nostalgia for easier times, we are refusing to meet that new era head-on. But refusing to compete doesn’t make the competition go away. It just means we lose by default.

Before we spend trillions on a scaled up defense we need to discuss whether the US wants to, and will be able in the future, to be a global hegemon with military dominance right up to China's beaches. After watching the U.S. blow trillions of dollars on misguided efforts to find a military solution to the Middle East's tribal problems. I have zero confidence in the U.S. military/foreign policy "blob" at this point.

What is the US getting for the money it spends? I couldn’t tell from this piece what the primary issues were, or how related the separate issues were. Is the primary issue that our defense industries need to import to many things from China or other places, so that currently with all our spending we are able to produce enough stuff, but we just can’t produce enough only domestically and with close allies? Is it that there’s too much waste in the defense spending for some of the reasons you mentioned above? Are higher wages in the US one of the reasons we spend so much?

I thought this was a good piece that runs counter to some commonly held beliefs, and I think it could have helped those of us who don’t pay as much attention to defense stuff to have a little more details about the disconnect between the apparent very high spending in the US compared to other countries and the inability to produce enough materials.

Are progressives less enthusiastic about military employment then they should be? The healthcare, pension, college/post grad tuition payments line up well with a lot of progressive goals, and for many conservatives it’s one of the main forms of big government they seem to tolerate. Similarly the industrial build out could target regions that would benefit from new industry which would bring blue collar jobs that progressives and “populist” conservatives like to push for. I doubt that support for the things your advocating for would be well received by such a coalition, but perhaps the public sentiment could push it that way.