Twilight of the economists?

The West's former top intellectuals grope for relevance in a fast-changing world.

I originally became well-known as a blogger for criticizing the economics profession — specifically, macroeconomic theory. Back in 2011-12, when the Great Recession was still lingering and the European debt crisis was raging, everyone wanted to hear why the economists had gotten it all wrong. By “the economists”, of course, they meant macroeconomists — nobody wanted to hear jeremiads against labor economists doing careful empirical studies of minimum wages, or tax theorists quietly working out the impact of changes in international tax policy. That stuff’s boring. Macro — the grand theories of booms and busts, growth, trade, inequality, and so on — has always been the glamor division of economics, and it was macro that people wanted to see taken down a peg.

And so we did. The intellectual revolution that I got to be a tiny part of in the early 2010s largely succeeded. In the decade since, the status of academic (macro)economists has fallen among the U.S. political class. The demotion began under Donald Trump, who downgraded the head of the Council of Economic Advisers from a cabinet-level post, and whose economic advisers consisted mainly of businessmen like Steve Mnuchin, right-wing think-tankers like Stephen Moore, and — to be brutally honest — hacks like Peter Navarro.

Biden has largely continued this trend. Janet Yellen was a prestigious economics professor, but Biden’s CEA leadership is mostly think-tankers, and its chief economist up until this month was Ernie Tedeschi, who has a Master’s in public policy and primarily worked as a private-sector economist in the finance industry. (This is not a knock on Ernie, who is a very smart and good guy. My point is that academic credentials are no longer as respected as they once were...and, as I’ll explain in the rest of this post, with good reason.)

Meanwhile, anecdotally, economists are no longer regarded as the all-purpose sages they once were — Tyler Cowen still has excellent advice on where to get lunch, but the fact that he is an economist no longer seems to lend that advice a special sheen of intellectual authority.

The blogger rebellion gave voice to built-up frustrations, but ultimately the cause of (macro)econ’s loss of prestige was its obvious failure to stay relevant in a changing world.

The financial crisis was a big part of that, of course — economic theorists largely failed to anticipate the possibility of such a crisis, to observe the risks building up, to anticipate the consequences of the crash, or to prepare a policy response — a very rare exception being Ben Bernanke, whom we were very lucky to have as Fed chair in 2008-9. (Ironically, the post-pandemic inflation has conformed much, much more closely to standard textbook macroeconomics, and few people have noticed or cared.)

But it wasn’t just the financial crisis. There was a whole litany of macro things that seemed to have gone very wrong, right under the economists’ noses. The profession barely even paid attention to the long rise in inequality that began in the 1970s, and when they did start to pay attention, they had few theories to explain it. Economists had almost dogmatically supported free trade, and were thus blindsided by the China Shock in the 2000s. And the relentless focus on shareholder value as the one goal of a corporation seemed to have financialized the economy, with managers now focused on slashing jobs to juice quarterly profits rather than investing in innovation for long-term growth.

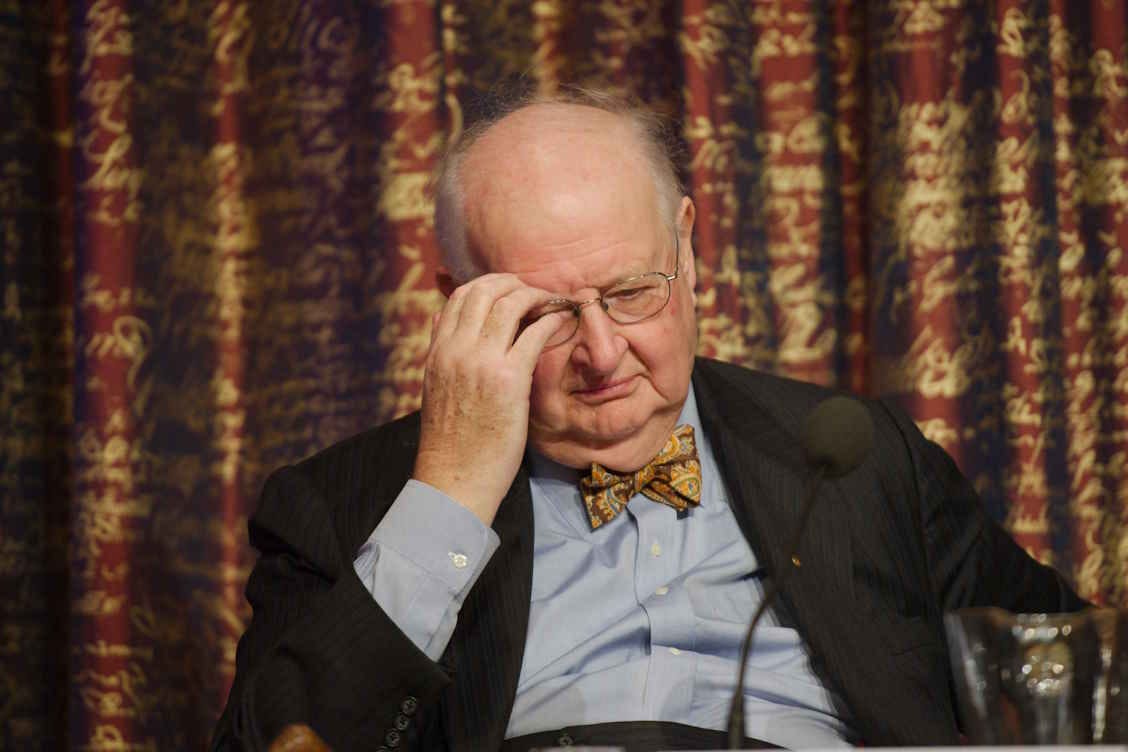

So it made sense to stop listening to (macro)economists quite so much — or at least, to no longer give them pride of place, and to supplement their perspectives with people from different backgrounds. But that left many economists themselves casting around forlornly for the relevance they once enjoyed. A prime example is Angus Deaton, who won the Econ Nobel in 2015, but who now spends much of his time making public mea culpas for both himself and his profession. In a recent post on the International Monetary Fund’s website called “Rethinking My Economics”, Deaton rattled off a whole list of things that he thinks economics has gotten wrong and needs to change.

This is, in principle, a healthy exercise. But Deaton’s post reads like a pastiche of populist political causes from the 2010s that are already starting to go stale, along with a few inside-baseball methodological gripes that he’s been nursing for a while. Ultimately it still seems to take it for granted that economists are still the West’s key intellectuals. It, and other critiques like it, have largely failed to grapple with what I see as the key problem — the fact that macroeconomic theory itself, as it’s practiced today, is ill-suited to helping us understand the problems we face.

So first let’s go through Deaton’s critiques, and then I’ll talk a bit about what I think the real problem is, and how it could be fixed.

Deaton’s complaints (and others like them)

Deaton lists many problems he sees in the econ field, but I think the main ones are:

Economics has ignored the role of power in determining economic outcomes

Economics has focused on efficiency instead of social welfare

First let’s talk about power. Deaton writes:

Our emphasis on the virtues of free, competitive markets and exogenous technical change can distract us from the importance of power in setting prices and wages, in choosing the direction of technical change, and in influencing politics to change the rules of the game. Without an analysis of power, it is hard to understand inequality or much else in modern capitalism.

The problem here is that Deaton doesn’t actually say what he means by “power”. Like “love” or “good”, the word “power” has many meanings. Economic theory already includes a number of types of power, including A) market power in oligopoly and oligopsony models, and B) bargaining power in various sorts of games. Deaton probably does include these things in his notion of “power”, since they involve the setting of prices and wages.

But he doesn’t mean only these things. His mention of “choosing the direction of technical change” strongly implies that he’s been reading the work of Daron Acemoglu, who doesn’t yet have a Nobel, but who is arguably the most important macroeconomist working today. Acemoglu, in his recent book Power and Progress with Simon Johnson, laid out a very novel and very weird definition of “power” — he basically thinks power means persuading people of your ideas. I’ll quote from my own review of that book:

Acemoglu and Johnson also spend a lot of time arguing that persuasion is…a form of power. They cite instances in which techno-optimists and businesspeople in 18th century England and 21st century America persuaded the public to enact pro-business policies, through articles, speeches, conversations, and so on…The authors don’t venture to say exactly why these techno-optimists’ pro-business vision prevailed — they write that “an idea is more likely to spread if it is simple, is backed by a nice story, and has a ring of truth to it,” but they admit that “quite a bit of this process [of persuasion] is random,” and declare that “you are enormously lucky if you get the right idea, with just the right ring to it, at just the right time.”

I have to admit, this kind of surprised me…I do not understand why we should put accidental success in a nonviolent marketplace of ideas in the same conceptual category as chattel slavery and feudalism. It seems to yield neither understanding nor solutions.

Really, I think what’s going on here is that economists have realized that there are social processes that are more complex than the simple theories that they know how to make, but which have important effects. And they’re choosing to slap the label “power” on those social processes as a sort of catch-all term, because it fits the politics of the times.

But labeling something is not the same as explaining it. In fact, macroeconomists have a bad habit of applying labels to things their models can’t explain, and then using the common-use connotations of those labels to pretend they understand how those mysterious objects work.

Another famous example is the use of the word “technology” to refer to total factor productivity, which an economist in the 1950s called “a measure of our ignorance”. Basically, total factor productivity is the part of the economy that can’t be explained by the amounts of labor and capital. It’s not really technology as we know it — it could include all kinds of things, from government policy to legal frameworks to corporate culture to trading patterns, etc. etc. But because they slapped the label “technology” on this mysterious number, a lot of economists were able to convince themselves that the successes and failures of engineers and scientists are what drive the economy on a yearly basis. Another example is “culture”, which is a word a lot of economists use to explain the relative economic success of various countries, despite never being able to measure it directly or explain how it works.

It’s pretty clear that economists like Deaton and Acemoglu now want to use “power” as another flavor of phlogiston — another label to let us feel like we’ve explained the so-far inexplicable. In fact, in his book with Johnson, Acemoglu writes:

Power is about the ability of an individual or group to achieve explicit or implicit objectives. If two people want the same loaf of bread, power determines who will get it.

This is just a tautology. Applying the label “power” to whatever mysterious forces lead to one person getting a loaf of bread does not help us actually predict who gets bread.

Now let’s talk about Deaton’s second big critique: economists’ focus on efficiency over social welfare. He writes:

In contrast to economists from Adam Smith and Karl Marx through John Maynard Keynes, Friedrich Hayek, and even Milton Friedman, we have largely stopped thinking about ethics and about what constitutes human well-being. We are technocrats who focus on efficiency. We get little training about the ends of economics, on the meaning of well-being—welfare economics has long since vanished from the curriculum—or on what philosophers say about equality. When pressed, we usually fall back on an income-based utilitarianism. We often equate well-being with money or consumption, missing much of what matters to people. In current economic thinking, individuals matter much more than relationships between people in families or in communities…After economists on the left bought into the Chicago School’s deference to markets—“we are all Friedmanites now”—social justice became subservient to markets, and a concern with distribution was overruled by attention to the average, often nonsensically described as the “national interest.”

This is a very classic critique — in fact, you’ll hear it in almost any introductory undergrad econ course. But it’s been around for so long that it’s no longer really true, because economists do often think about outcomes other than efficiency. A simple search of papers in top economics journals for the term “inequality” will reveal that there are many, many papers on the topic of what causes inequality. Key contributors to this literature include macroeconomists like Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, David Autor, Emi Nakamura, Xavier Gabaix, Benjamin Moll, Kenneth Rogoff, David and Christina Romer, Martin Eichenbaum, Janet Yellen, Sergio Rebelo, Robert Hall, Ricardo Reis, and many many others. Perhaps if you went back to the older generation of macroeconomists of the 1980s, you could find some who never worked on questions of inequality, but now those are rare.

As for other outcomes, education economists consistently use academic achievement as an outcome measure, health economists consistently use various measures of health such as mortality and disease burden, and crime and unemployment are frequently used (negative) outcome measures as well.

This does not mean that economists have studied every possible measure of human welfare. Community engagement, for example, is something I don’t often see economists talk about, and I also don’t think economists typically use family stability as an outcome (perhaps to avoid impugning the life choices of single parents). But in general, economists use lots of measures of human flourishing and welfare that don’t depend on efficiency or on income-based utilitarianism. Deaton is simply wrong here; he’s probably remembering how economics was done when he was young.

In fact, Deaton has complaints about economics other than the two I’ve mentioned, and none of the others really hits home either. For example, Deaton dismisses the “credibility revolution” — the turn toward natural experiments in empirical economics — as being too small-bore and short term:

[T]he currently approved methods, randomized controlled trials, differences in differences, or regression discontinuity designs, have the effect of focusing attention on local effects, and away from potentially important but slow-acting mechanisms that operate with long and variable lags. Historians, who understand about contingency and about multiple and multidirectional causality, often do a better job than economists of identifying important mechanisms that are plausible, interesting, and worth thinking about, even if they do not meet the inferential standards of contemporary applied economics.

But then in the very next bullet point, he calls on economists to have more humility!

We are often too sure that we are right. Economics has powerful tools that can provide clear-cut answers, but that require assumptions that are not valid under all circumstances.

It seems obvious to me that studying smaller questions where we can be more certain of the answers, rather than attacking big complex problems where answers will always depend on strong assumptions, is the very definition of humility. If Deaton wants economists to switch from careful small-bore experiments to grand sweeping historical theories, it’s a little odd for him to call for humility in the same breath.

Deaton’s critiques thus appear to contradict each other, suggesting they’re based on past arguments of his with other scholars, rather than on a coherent framework of what’s wrong with economics.

As for the policy implications of all these critiques, Deaton emerges with a sort of vague grab bag of mid-2010s populism:

Like most of my age cohort, I long regarded unions as a nuisance that interfered with economic (and often personal) efficiency…[But] their decline is contributing to the falling wage share, to the widening gap between executives and workers, to community destruction, and to rising populism…

I am much more skeptical of the benefits of free trade to American workers…I also no longer defend the idea that the harm done to working Americans by globalization was a reasonable price to pay for global poverty reduction…We certainly have a duty to aid those in distress, but we have additional obligations to our fellow citizens that we do not have to others…

I used to subscribe to the near consensus among economists that immigration to the US was a good thing, with great benefits to the migrants and little or no cost to domestic low-skilled workers. I no longer think so. Economists’ beliefs [about the benefits of immigration] often rest on short-term outcomes. Longer-term analysis over the past century and a half tells a different story. Inequality was high when America was open, was much lower when the borders were closed, and rose again post Hart-Celler (the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965) as the fraction of foreign-born people rose back to its levels in the Gilded Age.

This grab-bag of policy shifts is clearly a reaction to the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Some of the shifts are ethical — Deaton suddenly deciding that he cares about domestic workers and not international ones. Some are empirical, but based on comically flimsy evidence — Deaton deciding that immigration has negative long-term effects simply because immigration and inequality both rose in the U.S. since 1965. But they all have one unifying characteristic — they’re all obviously things that Deaton thinks America should have done in order to reduce the appeal of MAGA. In fact, I don’t have to infer this; Deaton has said this explicitly.

The fact is, although people enjoy thinking of economists as a bunch of libertarians, many surveys find that they’re mostly just standard Democrats. Economists like Deaton and Acemoglu looked at the election of Trump in 2016, decided — like other normie Dems — that this was an absolute calamity, and then went looking for ways we could prevent similar calamities in the future. But whereas many normie Dems simply concluded that Trump won because America is awash in racism, economists tend to go looking for economic factors, so they tended to buy the alternative explanation — that Trump’s election was a backlash to inequality, lack of opportunity, community breakdown, and so on.

And if economists want to believe that, fine. The problem is that economists don’t have a comparative advantage in being old men who read the news and shake their fist at it. Economists have a comparative advantage in doing economic research. But when Angus Deaton simply asserts that immigration caused inequality because both have gone up since 1965, he’s not doing economic research at all. In fact, Deaton’s main line of published research since he won the Nobel — the “Deaths of Despair” stuff — is not very rigorous at all.

If you think academic macroeconomics should be replaced with media narratives like this, you’re essentially giving up. It’s a nihilistic conclusion that macroeconomic research is pointless.

Fortunately, I don’t think things are that bleak. I may have started my blogging career bashing macroeconomic theory, but I actually think there’s plenty that can be done.

Macroeconomic humility

The real problem with macroeconomics is that the theories that the researchers use are so flexible that a skilled theorist can use them to reach any desired conclusion.

Briefly, there are three basic types of economic theory: game theory, partial equilibrium theory, and general equilibrium theory. Game theory generally involves well-defined, well-structured, limited environments, so it’s often useful for real-world stuff. Google auctions, for example, are designed with game theory, and they make a lot of money! Partial equilibrium theory is the thing you see me do in this blog with supply and demand graphs. It also describes a small, limited portion of the economy, so it’s often possible to make real, useful predictions with it (though machine learning will do better at this point).

But general equilibrium theories are different. They’re theories of the whole economy instead of just a piece of it — all the markets, all the consumers and producers, etc. The reason macroeconomists use general equilibrium theory is that if you’re talking about “big” outcomes like recessions, growth, inequality, and so on, you really have to take everything into account.

At this point, if you come from the natural sciences, you might be inclined to say “Oh God, the economists are going to try to make an Economic Theory of Everything, aren’t they?”. Well, no. It’s worse than that. A few economists did try to do that, and it did fail. But what most macroeconomists do, when they do general equilibrium theorizing, is to make thousands upon thousands of theories of everything.

Each general equilibrium model — and economists put out huge numbers of these every year — purports to be a theory of the entire economy. But each one is different — it’s modified in some way, in order to “study” some particular phenomenon. For example, I’ll pick on Daron Acemoglu again (because he’s incredibly successful, brilliant, and famous, so he can take it). Back in 2012, when Acemoglu and his co-authors wanted to answer the question of why Sweden’s capitalism is more “cuddly” than America’s, they made a general equilibrium model of the whole global economy, and added special features for entrepreneurs. Those features don’t appear in almost any other general equilibrium model.

None of these general equilibrium models are the same, and none of them agree with each other. The parameter values that the authors find when they estimate (or calibrate) one of the models don’t agree with the parameter values that other authors find in other models. And no one even checks. No one even cares. They just make a different, new “theory of everything”, with a ton of essentially new parameters, for each economic question they want to think about.

John von Neumann is said to have once declared that “With four parameters I can fit an elephant, and with five I can make him wiggle his trunk.” General equilibrium theories, because they don’t have to agree with each other, often resemble twenty parameters in a trenchcoat.

Now in a natural science, you would probably want to test these models against the relevant data, and if they didn’t fit the basic facts, you would chuck the model in the garbage and move on. Not so in economics. Models aren’t ever rejected by data in macroeconomics. It’s just not something anyone ever does. (People used to do this in the 70s, but all the models were getting rejected, so they stopped.)

For example, Acemoglu et al. (2012) concluded that Sweden’s “cuddly” form of capitalism produced fewer entrepreneurs. As many bloggers pointed out at the time, this is just false — Sweden has more entrepreneurs per capita than the United States, and it has more billionaires per capita as well. Acemoglu et al.’s model was just totally wrong about its key implication. But no one really cared. A version of the paper was eventually published in a top journal.

In practice, as the economist Paul Pfleiderer has noted, what happens with these thousands upon thousands of general equilibrium models is that they all go onto a musty old shelf somewhere — or whatever the modern digital equivalent is. Then, when an economist wants to support a certain policy, they simply search the musty old shelf for a model that reaches their desired conclusions, dust it off, and use it to back up their conclusion.

Naturally, you can keep this up as long as politicians, bureaucrats, businesspeople, and journalists keep listening to you each time. But this approach is going to end up getting things wrong a lot of the time, because the models that are being pulled off the shelf are not really disciplined by facts at all — they’re just a mathed-up rationalization of whatever the (macroeconomist) already thinks. Eventually your advice will go bad enough times that politicians, bureaucrats, businesspeople, and journalists will stop listening to you.

Which, more or less, is what happened to macroeconomists after 2008.

The way for macroeconomists to get their influence back is not to abandon formal modeling in favor of stuff like “immigration and inequality both went up since 1965, so immigration causes inequality”. The way for macroeconomists to get their influence back is to start getting more things right.

And that’s going to be hard. Building one true Theory of Everything for the whole economy is a monumental undertaking that will probably require many, many decades of research (assuming it’s even possible). So macroeconomists have to start smaller than that. They have to use partial equilibrium and game theory to pick off small parts of the economy to analyze. They have to use careful empirics to squeeze tiny drops of understanding from the blizzard of data. They have to figure out generalizable rules of how consumers, companies, workers, investors, and governments behave.

This isn’t just going to take a lot of hard work — it’s going to entail a loss of status. When macroeconomists could claim to have the answers to the really big questions, they were understandably regarded as sages, but now that people know they don’t actually have most of those answers, that respect is drying up. They need to come to terms with that. When famous old guys like Angus Deaton trying to issue grand pronouncements on what causes growth or what causes inequality, with little or no empirical support, they’re assuming they still have the status of pre-2008 macroeconomists, and that all they have to change are their pronouncements, and people will listen like they used to.

They’re wrong. No one who didn’t already think immigration causes inequality is going to change their minds because an old guy with a Nobel prize said so. What people will believe is scientific theories that actually work, like the auction theory that powers Google ads or the partial equilibrium theory that can (sometimes) predict changes in the price of oranges. Macroeconomists have to set aside grand theories that don’t work, and focus on making a few smaller-bore theories that demonstrably do work. That is the road back to relevance.

If anyone wants proof that individual contributions can actually make a difference, they can look at Ben Bernanke. He literally changed the course of history.

Paul Krugman's writings from the '06-'10 period stand up pretty well, I think. And a lot of what other economists were getting wrong, they were getting wrong because they seemed to have experienced a Great Forgetting.

https://archive.nytimes.com/krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/01/27/a-dark-age-of-macroeconomics-wonkish/

They were making stuff up to explain the crisis that would conform to their prejudices, when there were already quite good economic tools to analyze the problem; they just disliked the implications of those tools. He of course had the advantage of having _very_ closely analyzed Japan's dip into the liquidity trap, a decade earlier.

https://archive.nytimes.com/krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/10/09/is-lmentary/

He also had some great posts explaining Hyman Minsky, and one on how the requirements on certain index funds that they couldn't continue holding certain types of bonds after the credit ratings on those bonds were downgraded created a multiple-equilibria situation, with a backward bending demand curve. (Basically as the price of the bond falls, you'd think demand for it would rise -- except that at some point the lower price indicates that the rating has dropped, at which point suddenly demand gets WAY less, as index funds that are required to only hold, say, single A or higher, offload it. In fact they might start dumping it as it even gets close to the line, to try to front-run each other. So over some range, the demand curve goes the wrong way, and you can end up with two distinct equilibria. And one fund manager panicking about the possibility that there _might_ be a downgrade and sell-off, can _cause_ the sell-off, and then the ratings agencies see that there's no appetite for that class of bond, so the downgrade follows, and who's to say whether the downgrade would've arrived regardless, or was actually _caused_ by the panicky sell-off?)