Too many Americans still fear the future

Some progress is being made, but politics is getting in the way.

The Progress Studies folks that I hang out with a lot tend to complain that Americans have begun to fear the future instead of embracing it. I generally agree. But being the type of guy who looks for technological and explanations for every cultural phenomenon, I think it’s not very surprising that people in a stupendously rich, comfortable society like the modern United States would tend to be afraid of change.

Fundamentally, change means disruption, and disruption means risk. If you’re a car dealer, Tesla’s model of direct sales is a threat to your livelihood. If you work for a company that makes its money selling solutions to homework problems, LLMs are probably going to put you out of a job. Every single change to business models, government institutions, and technology threatens whoever came out on top in the previous equilibrium.

And despite their constant bellyaching, most Americans did come out on top in the previous equilibrium. The median American is far richer than the median resident of almost any other nation, and enjoys a material standard of living that others can only gawk at. If that’s where you are, any big technological, political, or institutional change carries at least some risk of knocking you from your privileged perch.

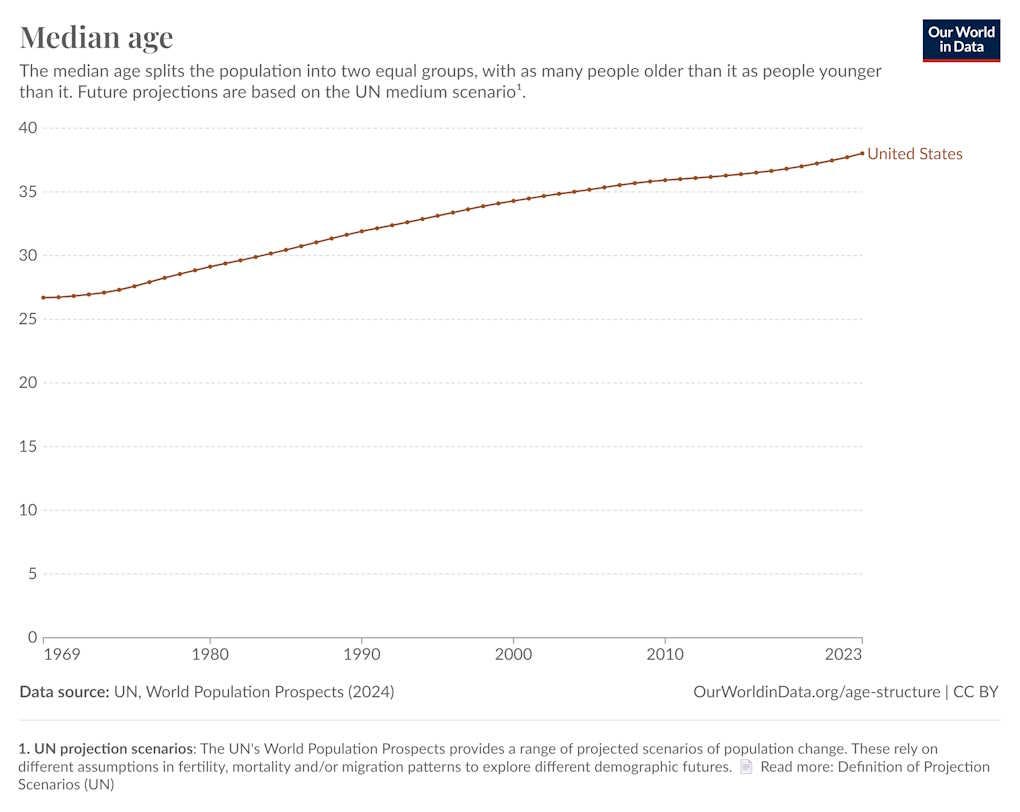

On top of that, America is getting older as a country:

Being older makes it harder to adapt to changes in the technical-social equilibrium. If you’re 18 and just starting out at the bottom, big changes are almost pure opportunity; if you’re 50 and you have a mortgage and kids in college and a high salary at a big corporation, you probably want to keep things stable.

And in fact, a common stereotype of Americans is that they demand to have more than their parents had, for less effort and risk:

But while there’s a grain of truth here, I think it’s overstated. Given all the economic incentives to resist change, I’m actually surprised that Americans embrace the future as much as they do!

Green shoots of bravery

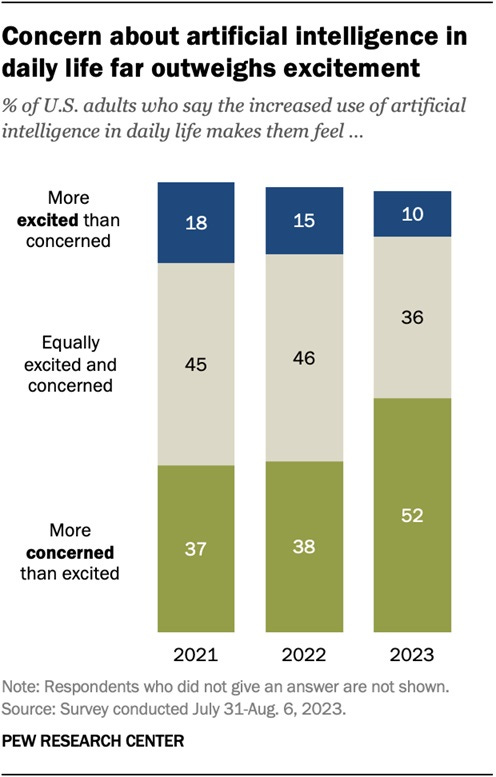

Consider AI. On one hand, more Americans feel concerned rather than excited about the technology:

But these concerns don’t seem to be strong enough to influence policy very much. Whereas Europe has decided to try to regulate AI instead of building anything itself, the U.S. is charging ahead — Trump has signed an executive order doing away with “AI safety” concerns at the federal level, and Gavin Newsom vetoed an AI safety bill in California.

Or take housing. Of course I talk all the time about how big of a problem NIMBYism is in America, and how a lot of politically powerful homeowners have created a rent crisis by trying to protect their quiet empty streets from townhouses and duplexes. That is true. But relative to changes in population, America has actually been building a decent number of homes since the pandemic:

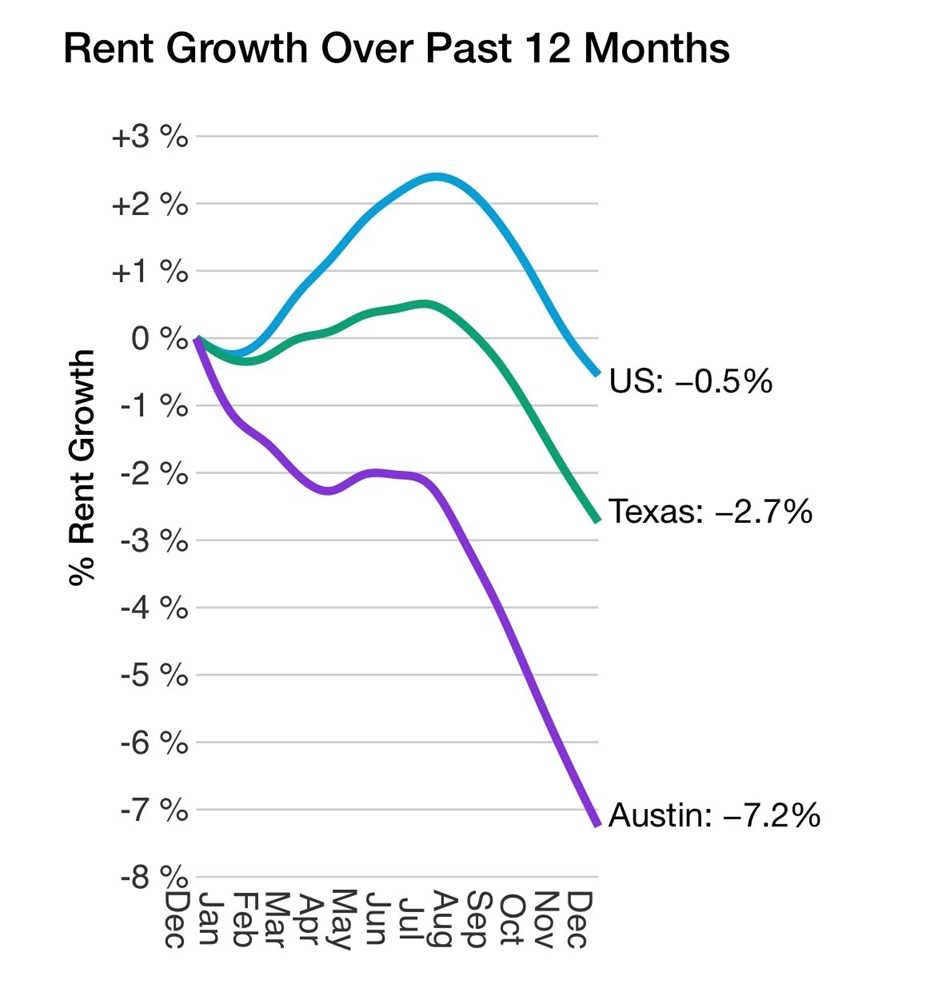

Some parts of the country are far outpacing the average. The skyline of Austin, Texas looks almost totally unrecognizable from a decade ago, with a forest of new tall buildings:

And the city has built so much housing that rents have plummeted:

For a third encouraging example, look at entrepreneurship. After decades of declining business formation, there has been a huge surge of Americans starting companies since the pandemic, especially in high-tech fields:

Business formation isn’t the only measure of increased dynamism, either. More Americans are looking to switch jobs than in the 2010s.

This is all very encouraging. It suggests that many Americans are rising to meet the challenge of a risky, uncertain future, rather than hunkering down and protecting their wealth. Perhaps the “roaring 20s” are really seeing a shift back toward the bold optimism that the Progress Studies people have been hoping for.

But if so, the shift is still very incomplete. There are still a lot of important ways in which Americans — especially the leadership and the politically engaged class — are trying to resist the future instead of riding the wave.

Republicans fear hardware, Democrats fear software

The most egregious recent example of future-fear comes from our newly elected President, Donald Trump. Not content with freezing approvals for wind power on federal land and water, Trump has now paused solar power as well:

The Trump administration is pausing approvals for new renewable energy projects on public lands and in public waters…The Interior Department quietly issued an order Monday that blocks activities that enable renewable development on federally-owned lands or offshore…For 60 days, the government will not issue any leases, rights of way, contracts or “any other agreement required to allow for renewable energy development.”…It comes as Trump has launched an assault on wind energy in particular, issuing an executive order that pauses new approvals for wind energy. But applying the pause to renewables broadly is an escalation — pausing solar energy action as well.

I don’t want to paint this as a catastrophe yet. First of all, it’s only on public land; most renewable energy is built on private land. And second, it’s not clear whether this is a temporary move that will lapse after two months’ time, or the beginning of a more permanent assault on solar and wind energy. But from everything Trump is saying in interviews, it seems clear that he just doesn’t like solar energy at all:

What’s going on here is, fairly obviously, some combination of simple old-guy aesthetic NIMBYism (“those massive solar fields”) and right-wing culture wars. The latter has been caused by decades of Americans seeing energy technology as being fundamentally about climate, rather than about energy itself. In a post back in December, I wrote the following:

The fact is, climate change mitigation is incredibly — almost totemically — unpopular within the GOP and the conservative movement. There is a strong knee-jerk opposition to climate activists, who are generally seen as communists hiding their radical anti-capitalist agenda behind the facade of a global emergency.3 Anything the climate people want, the Republicans will say “no” to.

So when we rhetorically and mentally put electrical technology in the climate bucket, it immediately becomes a non-starter with around half the country…It would be fairly pathetic if America became a second-rate power in the 21st century simply because we collectively associated the revolutionary technologies of the day with hippies and tree-huggers.

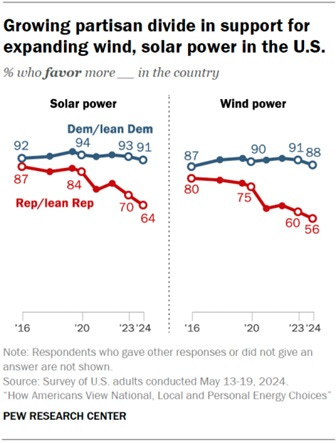

You can easily see this in polls. Even as solar power has gotten radically cheaper, Republicans have become more hostile to the technology:

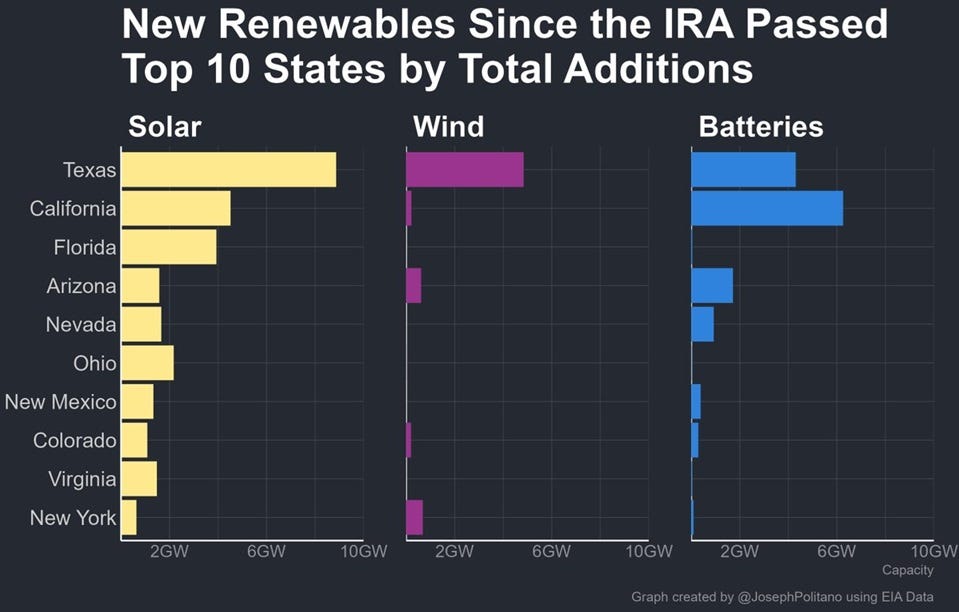

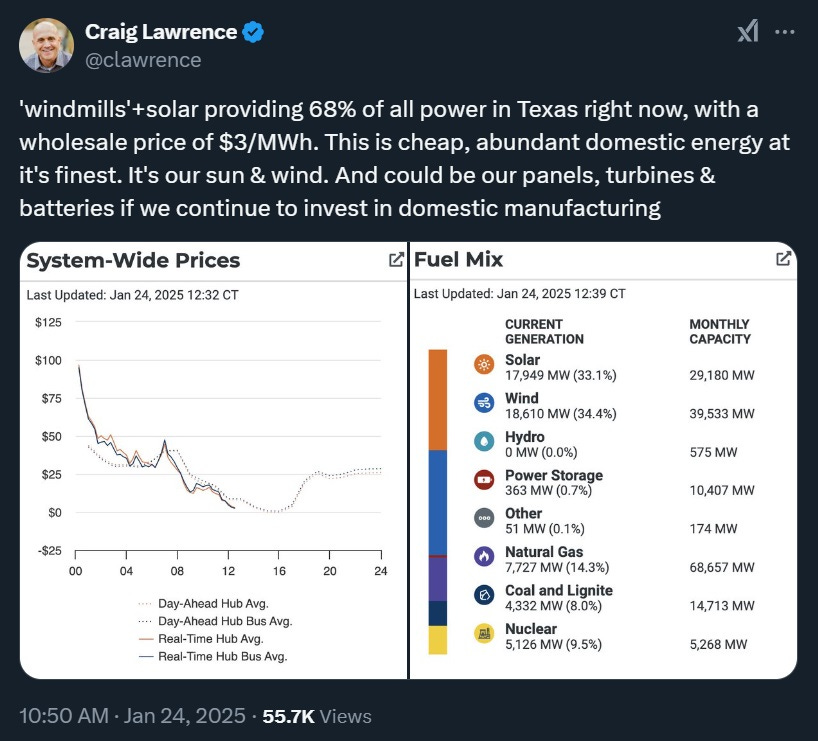

Solar power is the cheapest form of energy now, even with zero subsidies. One state that realizes this is Texas, which is building more solar than any other state:

In fact, at some times of day, renewables now provide the bulk of Texas’ power:

The fact that Texas is building the most solar and wind should be proof that these technologies simply work. The rest of the U.S. isn’t far behind, though:

If you point this out on social media, of course, a bunch of people will immediately mob you and say “Nuclear is better than solar!”. That’s wrong, of course. Nuclear’s compactness makes it useful for some niche applications, but its high costs and lack of a learning curve means that when land is available for solar, nuclear simply isn’t competitive at all. You can tell this because China, which is building far more nuclear plants than any other country on the planet, is building far more solar power than nuclear.

So anyway, Trump is trying to stand in the way of a cheaper, better power source replacing an old, inferior power source. It’s part of a general pattern of Republicans being afraid of the physical technologies of the future — other examples include electric vehicles and vaccines.

If Republicans tend to fear the future of hardware, then Democrats fear the future of software.

The Biden administration consistently went after big tech companies in its antitrust push — a puzzling decision, given that the price of software is hardly what’s breaking most people’s bank accounts. But the “Neo-Brandeisian” school of antitrust, of which Biden’s FTC chair Lina Khan was one of the creators, believes that harms to consumers are not the main reason for breaking up big companies and preventing mergers. The Neo-Brandeisians believe that the main problem with big companies is that they accumulate too much power — not just market power, but also political power.

Essentially, Democrats went after Big Tech because they thought tech companies had gotten too politically influential. Ironically, this political antipathy ended up being one factor pushing the tech industry to the right and resulting in the election of Trump.

Democrats have also been behind the “AI safety” push, which sees AI primarily in terms of its dangers instead of its opportunities. Biden was the one who issued the executive order on AI safety that Trump just repealed. And Scott Wiener, a California Democrat whose ideas I almost always endorse and respect, was responsible for a bill that would have restricted AI had it not been vetoed by the governor. Those restrictions were, in my assessment, pretty pointless, especially because China would have just proceeded with largely unfettered AI research anyway — as it ended up doing with DeepSeek.

Why did some Democrats want to hobble AI? Again, the most likely explanation is that they were concerned with limiting the power of the tech businesspeople who created the AI. This need to limit the power of the technologist class was the core message of Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson’s book Power and Progress, which embodied ideas that seem to have been influential on the left:

Ultimately, the Democrats’ desire to hobble the software industry doesn’t seem too different from the Republicans’ attempts to hobble the green energy industry. In both cases, fear that the technology will empower the wrong people — hippies and commies in the case of hardware, “bro-ligarchs” in the case of software — ends up translating into antipathy toward the technologies themselves. This stands in contrast to the mid-20th century, when Americans, recently unified by World War 2, simply assumed that new technologies like vaccines, airlines, and TV would be created for their own benefit.

I think this is teaching us something important about why countries start to fear the future. It’s not just pure economic incentives or personal risk. When societies become politically and socially divided, people begin to fear that new technologies will empower their political enemies. When people start to believe that their enemies will rule the future, a natural impulse is to stand athwart history yelling “Stop!”.

So if we want to return to a society that eagerly embraces the new, reducing our political and social divisions might be a prerequisite. Americans need to know that when the future comes, we’ll all get to go together.

You downplay the antitrust issues of big tech. Nothing new, but here are some:

1. They are all conglomerates with sometimes completely different businesses (online retailer and cloud business, search engine and entertainment, hardware provider and apps ecosystem etc.) and will add more when they see opportunities. While this is not illegal, this does point to concentration of market power.

2. They buy competitors to try to control their market (a single company controls most social media).

3. They buy dozens of competing startups when they think they can add value to their business or see a potential threat.

4. They control internet platforms or ecosystems, making it harder for others to compete

5. They lock in consumers, (how easy is it to move to a different social medium when all your friends dont? ). While this is how the internet works, this is a huge advantage.

And while not a competition issue, they control our data, they control freedom of (hate) speech, can move elections, are addictive and have influence on our mental health that we are only beginning to understand.

Yes, they have been great for the US economy, are the envy of the world and I use them a lot.

But I dont think you can deny they have lots of (market) power, raising many issues. I would be surprised if we continue to accept this, maybe the US will, but the rest of the world?

You nailed it. What is to be done? Maybe nothing. Maybe Texas, the home of oil will just continue to build solar because it makes sense. And who knows it’s when and what peak oil is but there is no peak sun 🌞