The Players on the Eve of Destruction

The insanity of war has returned to our world.

I’d like some help finding a poem, if any of you happen to know it. I read it when I was a teenager, and I forget who it was by — possibly Louise Gluck. Anyway, the poem was about a woman watching two happy young lovers, and wanting to warn them that their love would eventually fade.1

It’s hard to avoid a similar kind of maudlin feeling when I visit Taiwan, as I now have every year since 2022. New Year’s Eve in Taipei is a something worth seeing — an entire shopping district in the middle of the city gets closed off and flooded with young people, basically becoming a gigantic all-night block party. At midnight, right in the middle of that party, fireworks shoot off of the city’s towering skyscraper, Taipei 101. It’s the kind of thing safety regulations would never allow in America, and probably not even in Japan. Everyone cheers wildly, and they dance and drink until morning.

As the fireworks exploded and thousands cheered, I was suddenly reminded not just of that poem about the two lovers, but of some bit characters from the Iain M. Banks novel Consider Phlebas. The Players on the Eve of Destruction were gamblers who would travel around the galaxy to places about to undergo an epic catastrophe — a supernova, a war, and so on — and play games right up until the very last moment. I wondered if I was one of them now.

Humanity’s curse is that we can peer into the future. We see a pandemic begin to spread, and we know that in a few weeks it will probably be everywhere. We see banks begin to fail, and we know that in a few months a lot of people will probably be out of a job. When my rabbit has to go to the veterinarian, I’m nervous hours in advance, while he calmly munches hay, oblivious to the onrushing inevitability of unpleasantness.

On New Year’s Eve in Taipei, it’s hard for me not to think about the future that might be coming. It’s hard not to see the streets filled with merrymakers strewn with bodies instead, the shopping malls lying shattered in chunks of rubble, the young people searching in vain for their parents. It’s hard not to look at the towering spectacle of Taipei 101 and imagine it toppled and broken.

It’s hard for me. But it doesn’t seem to be hard for most of the Taiwanese people, who go cheerfully about their partying and their jobs and the quotidian routines of daily life with as little apparent terror as my rabbit munching hay. Even as the titanic battle-fleets of a menacing empire surround their home, even as the empire’s state media bellow threats of war, Taiwanese people stroll through night markets and sip Ruby #18 tea and line up for the latest cat cafe. There is an easy, laid-back tranquility to this culture like nothing I’ve ever seen, not even in Amsterdam or a California beach town.

“It’s like earthquakes,” Taiwan’s Minister of Digital Affairs told me when we met up two years ago. She meant that the Taiwanese had become so used to living under the constant threat of invasion and war over the last seven decades that they had learned not to sweat about it too much. Perhaps that was even true. If so, I would recommend that Taiwanese people have a little less equanimity and a little more urgency. The ability to see into the future is a curse, but it’s also a blessing, as it allows humans to act to be ready for the terrible things ahead. Anxiety is the price of preparedness.

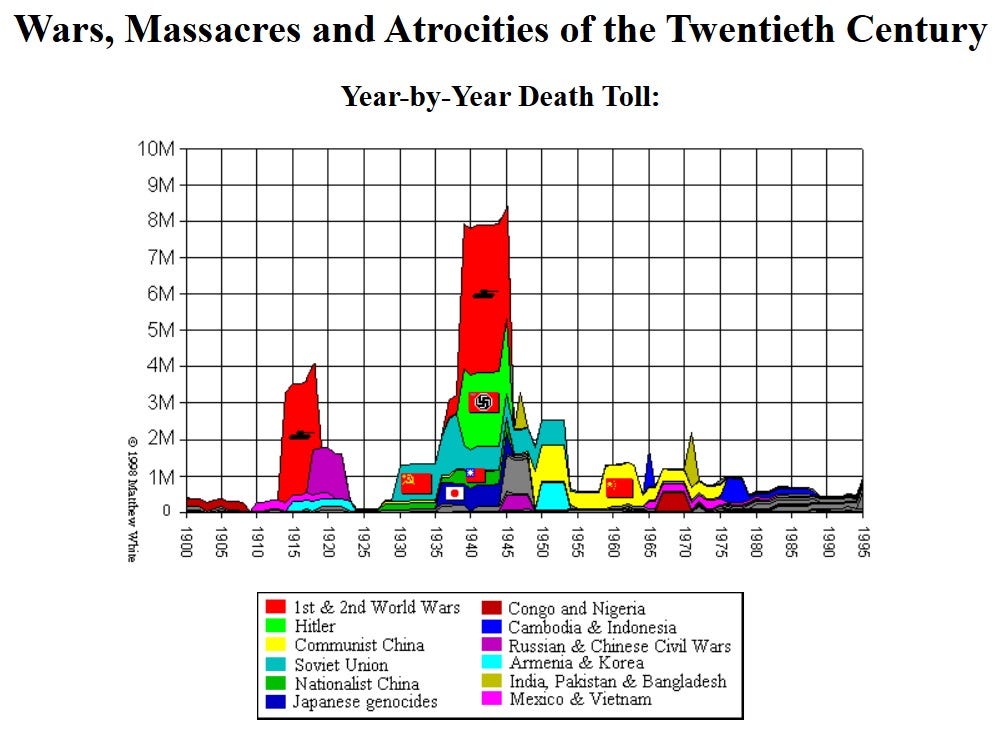

War has returned to our world. For some it never left, of course — if you were in the DRC in the 1990s or Iraq in the 2000s, the fact that life was peaceful in Shanghai or Berlin or Tokyo meant little. But it would be intellectual dishonesty not to acknowledge the vast difference between typical wars and those involving great powers. No matter what data source you use, any chart of the deaths from war will show the World Wars rearing above the rest like two grim towers. This chart is 25 years old, but it still hits hard:

War is never completely gone from the human experience, but when the big boys come out to play — or when they collapse — things get kicked up to another level entirely.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, everyone knew something had changed. The Iraq War had been a harbinger of what was to come — a great power launching a war of choice against a smaller, non-threatening state. But Ukraine was different — Russia wasn’t just recklessly intervening in a neighboring country, but attempting to swallow it entirely. The age when great powers competed only by proxy and by temporary interventions was over, and the age of conquering empires had returned. The Russians themselves have said this openly, and the Chinese realized it as well:

[Xi Jinping] has repeatedly warned Chinese officials that the world is entering an era of upheaval “the likes of which have not been seen for a century.”…

“The old order is swiftly disintegrating, and strongman politics is again ascendant among the world’s great powers,” wrote Mr. Zheng of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen. “Countries are brimming with ambition, like tigers eyeing their prey, keen to find every opportunity among the ruins of the old order.”

If you think about this idea from first principles, its fundamental insanity becomes apparent. Spend a few days in Taiwan, and tell me honestly if there is anything wrong with it — some terrible injustice that needs to be corrected with saturation missile strikes and invasion fleets. You cannot. The people here are happy and wealthy and productive and free. The cities are safe and clean. There is no festering racial or religious or cultural conflict, no seething political anger among the citizenry. Everyone here simply wants things to remain the same.

And yet there is a good chance they may not be granted that wish. High explosives may soon rain down on their homes and their families, and an army of stormtroopers may march in and take all of their freedoms from them. And if this happens, it will be because of the will of men far away — an emperor on a throne, generals hungry for glory, bored malcontents behind a computer screen. If the peaceful, unthreatening people of Taiwan suffer and die, it will be because those distant men decreed that they should.

Why would you do this?? Why would anyone want to launch wars of conquest? The world has progressed beyond the economic need for warfare — China will not become richer by seizing the fabs of TSMC or the tea plantations of Sun Moon Lake. The mostly stable world created in the aftermath of the Cold War was good not just for Taiwan, but for China as well. Why topple it all chasing a dream of empire?

The only possible answer here is that the world is created anew each generation. We still call China by the same name, we still draw it the same way on a map, but essentially all of the people who remember the Long March, or the Rape of Nanking, or the Battle of Shanghai are dead and gone. The hard-won wisdom that they received as inadequate compensation for suffering through those terrible events has vanished into the entropy of history, and their descendants have only war movies and books and half-remembered tales to give them thin, shadowed glimpses.

And so the new people who are now “China” are able to believe that war is a glorious thing instead of a tragic one. They are able to imagine that by coloring Taiwan a different color on a map, their army will redress the wrongs of history, bring dignity to their race, spread the bounties of communist rule, fulfill a nation’s manifest destiny, or whatever other nonsense they tell themselves. They imagine themselves either insulated from the consequences of that violence, or purified and ennobled by their efforts to support it.

They do not understand, in the words of William T. Sherman, that “war is destruction and nothing else.” Nor do they think very hard about the future of the world their short, glorious conquest of Taiwan would inaugurate — the nuclear proliferation, the arms races, the follow-on wars. The German and Russian citizens who cheered their armies and threw flowers as they marched to the front in 1914 could not imagine Stalingrad and Dresden thirty years later. We have seen this movie before.

From the supporters of empire, the rejoinder is always: Why resist? Why not simply invite in the armies of the empire next door, take the knee, and submit to being the emperor’s subjects? Wouldn’t a world united under the iron grip of a single dictator be a peaceful one? Was this not why the Ming Dynasty knew two centuries of peace, and the Qing? Perhaps Xi Jinping’s China and Putin’s Russia are not the most free or pleasant places to live in the world, but isn’t that life preferable to searching for your mother’s corpse in the rubble of your family home?

Isn’t the true tragedy that humans are too obstreperous and obstinate to simply submit to the bringers of order? Won’t we all feel better when the messy business of conquering is over and we can enjoy the order that the conquerors bring? Isn’t every peaceful, rich, happy nation on Earth built on the bones of the defeated — including Taiwan itself?

The answer to this challenge is neither easy nor obvious. But looking at what the new empires of the 21st century have wrought, I think it’s clear that the type of regimes who would shatter the peaceful world of the late 20th are not the type who would follow up a quick conquest with years of peace. The conquered areas of Ukraine are living nightmares, where the men are press-ganged into wars for further conquest, suspected dissidents are tortured without due process, women are subject to arbitrary rape, and families are plundered at will. Russia itself is marginally less repressive than its conquered territories, but there is a reason why so many people want to leave.

Nor is there any indication that this new Russian empire will forsake its orientation around war and conquest anytime soon — after all, after Ukraine there are still the Baltics, and Moldova, and Poland, and even Germany. Putin was not satisfied with Georgia in 2008, nor with Crimea and the Donbas in 2014, and neither he nor his successors is likely to be satisfied with Ukraine if it falls. The modern Russian state is oriented around war — the machine will grind on, and forced conscription in each conquered area will be used to fuel the cannon fodder for the next conquest, as it was in the days of the tsars and the khans.

What about China? On one hand, unlike Russia, it’s a productive, manufacturing-oriented state — a repressive place in many ways, but unless you’re a Uighur in Xinjiang, not exactly a nightmare. Hong Kongers have experienced a steady loss of political and cultural freedoms since the city’s peaceful resistance was crushed a few years ago, but people there are not yet being sent to the camps or slaughtered in the street.

And yet China is becoming a more repressive place over time, as its power grows. The government is building hundreds of new detention facilities all across the country for the emperor’s political opponents. The civil society that began to flourish in previous decades has been increasingly ground into nothingness. The bargain in which the state provides economic growth in exchange for rights and freedoms has broken down, and Chinese people are now asked to accept the authoritarianism without the growth. Discontent may not yet be so apparent that tourists are inundated with expressions of rage, but signs of dissatisfaction are on the rise, and those who can get money out of the country are generally doing it.

If you bend the knee to Earth’s new empires, you are essentially making a bet that these trends will reverse themselves — that the repression is a temporary expedient, a necessary transitory phase while the empires establish order, after which things will get better for your grandchildren. There are many times and places in history when such a bet would have actually paid off. But the Ukrainians who are resisting Russian conquest have decided that given their history with previous incarnations of that empire, it’s a bad bet this time. Whether Taiwan will resist or capitulate in the face of overwhelming force remains to be seen, but the other nations in Asia — Japan, Vietnam, Korea, etc. — have a long history of refusing to incorporate themselves into Chinese empires.

Until now, the independence of those countries has been guaranteed by the intercession of a more distant great power — the United States. But that once-mighty nation is increasingly not in a condition to resist the Chinese empire — or even the far weaker Russian one.

A decade of roiling social unrest and three decades of increasingly intractable political division have turned the country inward; Americans are too afraid of the enemy next door to worry about a friend six thousand miles away. And decades of pro-stasis policies — a toxic bargain between progressives who wanted to shackle industry and conservatives who wanted to shackle government — have paralyzed the country’s ability to respond to new challenges and threats. While China leaps from strength to strength in robotics, drones, shipbuilding, AI, and a thousand other products, America’s progressive intelligentsia view new technologies and the companies that build them with suspicion and distrust. While China dominates global manufacturing, America forces companies to hold a block party before building an EV charger.

And whether the U.S. is even committed to global freedom in the abstract is now an open question. The fabulously wealthy businessmen who have the greatest influence in the new administration openly mock the courageous Ukrainians who stayed and risked death to defend their homes and families from the rape of Russia’s invasion — even though if war ever came to their own doorstep, they would be the first to flee, clutching their Bitcoin to their chests like sacks of gold. An aging Donald Trump indulges in idle fantasies of staging his own territorial conquests in the Western Hemisphere, LARPing the new fad for imperialism even as his peers practice the real thing overseas.

America, like every other nation, has been created anew as the generations turned. This is not the America of Franklin D. Roosevelt, or even the America of Ronald Reagan. My grandparents are dead. Their hard-earned warnings are abstract words fading into memory, and I wonder if the world they won will outlast them by much.

And so across the sea, the old stormclouds gather again. In the seas around Taiwan, an armada assembles. Across the strait, the emperor orders a million kamikaze drones, hundreds of nuclear weapons, a forest of ballistic missiles, and a vast new navy. In Taipei, the sun is out, and people sip their tea, and eat their beef noodle soup, and and try not to think too hard about whether this will be the year the old world finally gives way to new.

My friend Vanessa ended up finding the poem with the help of GPT. It was “The Garden”, by Louise Gluck. Here it is:

—

The Garden

Louise Glück

I couldn’t do it again,

I can hardly bear to look at it—

in the garden, in light rain

the young couple planting

a row of peas, as though

no one has ever done this before,

the great difficulties have never as yet

been faced and solved—

They cannot see themselves,

in fresh dirt, starting up

without perspective,

the hills behind them pale green,

clouded with flowers—

She wants to stop;

he wants to get to the end,

to stay with the thing—

Look at her, touching his cheek

to make a truce, her fingers

cool with spring rain;

in thin grass, bursts of purple crocus—

even here, even at the beginning of love,

her hand leaving his face makes

an image of departure

and they think

they are free to overlook

this sadness.

Beautifully written and gut-wrenching piece, Noah. Thanks for speaking up for Taiwan. As someone living in Taiwan who sees its hard-won democratic life every day, it means a lot to me (and to so many others).

A great read.

But deep down, I think that everything else you discuss is subordinate to this paragraph:

"The only possible answer here is that the world is created anew each generation. We still call China by the same name, we still draw it the same on a map, but essentially all of the people who remember the Long March, or the Rape of Nanking, or the Battle of Shanghai are dead and gone. The hard-won wisdom that they received as inadequate compensation for suffering through those terrible events has vanished into the entropy of history, and their descendants have only war movies and books and half-remembered tales to give them thin, shadowed glimpses."

There are two threads implicit here.

One is human nature. I am an old man, but I have never resolved myself to human nature as it actually exists. Anyone who absorbs global history over the centuries has to face the fact that mass freedom or happiness is accidental; rather it's the individual and group drive for power and dominance that determines history. Everywhere I look, on all continents and at almost all times, those who thought that they could take from their neighbors and subjugate their neighbors did so. Especially if their neighbors were doing well and, perhaps, focused more on enjoyment of their blessings than on strength.

Humans, of course, are far from alone in this nature. I am a bird watcher, and every year I watch the birdie equivalent; Cardinals break their necks fighting the Cardinals in the window, and Robins lie dying along the roadside caring to their final breath only about the expansion of their territory.

The other thread here involves the protective qualities of memory. However, from the caves to Sumeria to Rome to 1945, memory alone rarely served as an antidote to human nature. So what changed after World War II? I would argue that it was communications technology. Print became truly dominant only when steam power made printed material almost universally accessible, and, like all technologies but especially communications and transportation technologies, it profoundly changed humans. In large part because print was a memory multiplier. It vastly increased the reflection upon past experience and wisdom, to the point that this reflective nature became a deep seated cultural value. Such that reflective and wise became attractive traits in leaders. Especially once the World Wars were entered into humanity's memory bank.

Of course, this change in human history resulted in winners and losers. The United States was probably the biggest beneficiary; racing under a yellow flag is great when you have the lead. The spiritual descendants of raiders and pirates were the losers, as were individuals who otherwise might have risen in life through physical might.

When you bemoan the lack of memory of, say, the Rape of Nanking, you are really bemoaning the replacement of print society with online society, which turns out to favor an entirely different kind of thinking, and privileges different voices. Reflective voices lose; bristling aggression wins, and thus looks attractive in prospective leaders. Including in democracies. And all the more so, because we have a substantial reservoir of discontents who really were disadvantaged in the print era, and whose discontent has long been mocked by print society.

So, I don't know about the world being recreated anew every generation -- such rapid change is a very modern phenomenon. But I am pretty sure that this generation does indeed face a world fundamentally different from the one I was born into. And I don't believe that we Americans are doing any better at facing up to serious threats than are the Taiwanese partiers.