The George Floyd protests were not a civil war (repost)

And the less we collectively remember them as one, the better.

I’m traveling again today, heading back to the U.S., so here’s another repost from the archives.

One of my big theses is that social unrest in America hit a peak in 2020 and early 2021, and has been gently declining ever since. The peak corresponded to two big events — the Floyd protests and riots of summer 2020, and the coup attempt of January 6th, 2021. How we remember those events will be important for the process of national healing.

In late 2021, when Kyle Rittenhouse was acquitted, I wrote a post looking back at the Floyd protests. The post hasn’t aged well in all regards — Rittenhouse eventually did succumb to the temptation to become a right-wing media influencer — but I think that my characterization of the events of summer 2020 is still accurate and still relevant. Although they were disruptive and divisive and occasionally violent, the Floyd protests weren’t the beginning of a revolution (as a few on the left hoped), nor were they the opening shots of a civil war (as many on the right feared). We shouldn’t necessarily dwell on the Floyd protests, but I think it’s useful to remember the facts and put them in their proper context.

The Kyle Rittenhouse saga has petered out. Rittenhouse was, rightfully or wrongfully, acquitted of murder in the killing of two protesters in Kenosha, WI back in August 2020. There were a few scattered protests against the verdict, and in Portland the protests even turned violent. On Twitter, many right-wingers crowed in victory and many progressives gnashed their teeth and issued dark, maudlin statements about the state of the country, but a day later the news cycle was on to other things.

Some leading figures on the Right have tried to make Rittenhouse into a hero of their cause. Madison Cawthorn offered Rittenhouse a Congressional internship, and Matt Gaetz suggested he might do so as well. Right-wing humor sites chimed in with some unbelievably bad-taste jokes about Rittenhouse being a warrior against communism.

But Rittenhouse appears not to be taking the bait. In an appearance on Tucker Carlson’s show, he shocked the Right when he acknowledged systemic racial bias in the justice system, saying: "Imagine what [prosecutors] could have done to a person of color, who maybe doesn't have the resources I do".

Now Rittenhouse has declared that he’s destroying the gun he used to shoot the two protesters — a stark contrast to George Zimmerman, who auctioned off the gun he used to kill Trayvon Martin. It’s too early to be sure, but it looks like Rittenhouse will probably eschew the role of violent champion that the Right wants him to take up, and live a quiet life of regret over his actions.

Which would only serve to drive home a message that Americans badly need to hear: Our country is not in a civil war. Yes, we have experienced a time of heightened unrest over the past eight years or so, with scattered incidents of political violence. Yes, a dispute over the 2024 election could actually send us into civil war. But we are not there yet, and people who act as if we are are being distinctly unhelpful.

And a big part of realizing that America is not in a state of civil war is realizing that the George Floyd protests of 2020 — the apex of mass unrest — were not a civil war. A lot of people on all sides talk as if the mass outpouring of anger in 2020 was a violent national conflict between Left and Right…but it wasn’t.

Let’s review the facts.

The protests were mostly peaceful

When I was a kid, Los Angeles had six days of riots. In those six days, 63 people died, and over 2000 were injured. That was in one city. In the King assassination riots in 1968, which took place in over 100 cities and lasted almost two months, the death toll was 43. The Watts riot of 1965, in one neighborhood of one city, claimed the lives of 34.

In the George Floyd protests, which took place in literally thousands of cities and lasted for months, involving an estimated 15 to 26 million people — by far the largest protest America has ever seen — a total of 25 people were killed. You can read a list of the deadly incidents here.

In other words, the Floyd protests were much less deadly than previous episodes of American unrest. That’s true in terms of total death, but especially true in per capita terms.

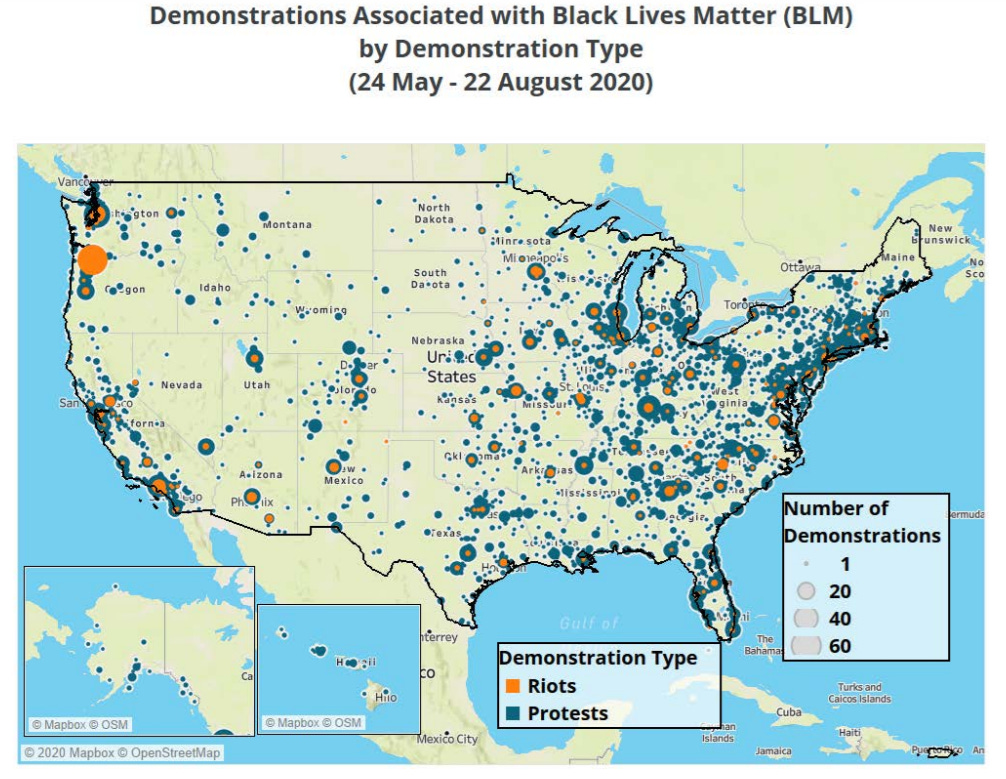

It’s also true in terms of the number of individual protests where violence was reported. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), along with some researchers at Princeton University, created a database of locations where peaceful protests were reported and locations where violent protests (riots) were reported between May 24 and August 22 of 2020. They found reports of peaceful protests in 2400 locations, and reports of riots in 220 locations. Here was the map they produced:

There are a few cities where riots appear to have outnumbered peaceful protests — most notably Portland (where all reported demonstrations were violent!), but also Seattle, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, and a handful of other cities. But overall, the map has a lot more green than orange. In the average town, the average protest didn’t contain any rioting.

And the definition of “rioting” here is extremely expansive. It’s based on police reports of violence, which includes things like smashing street lights or cars or toppling statues. It also includes looting, which (as we’ll see shortly) is usually not done by protesters themselves. So even with that very expansive definition of “violent protest”, less than 10% of protests were violent.

Now, 220 violent protests is a large number! And a few of the riots — in Minneapolis, in Washington, D.C., in Kenosha — were pretty big and scary. And the violence in Portland was bizarre, prolonged, and highly disruptive to the city. Nor would I ever want to minimize the importance of the 25 people who lost their lives.

But we really, really have to take percentages into account here. We all suffer from the availability heuristic — the fact that the media takes every violent incident and shoves it directly into our faces creates the illusion that those incidents are typical, even when they’re rare. And in the case of the Floyd protests, the media — including social media — was selecting the most violent and upsetting incidents from three months of protests involving 20 million people. 20 million people is an almost inconceivably huge number of people. If you get 20 million angry people out in the streets — 6% of the entire population of the country! — you are going to have some violence, no matter how much the overwhelming majority of those 20 million manage to restrain themselves. That’s especially true in America; this is an extraordinarily violent country, with over 50 murders a day on average. Three months of the biggest protests the country has ever seen resulted in about 1/2 of one day’s worth of killing.

We shouldn’t minimize that, but it just doesn’t sound like a civil war.

The police vs. the people?

The George Floyd protests were protests against police brutality and racism. Thus, if the incident were a civil war, one might expect it to be a war of police against protesters. But in fact, very few were killed on either side of that “war”.

Police in many areas certainly conducted themselves very poorly in the Floyd protests. There were over 400 videos of police being violent toward peaceful protesters, including a few very shocking and grisly ones. But police killings during the protests were extremely rare. Looking at the Guardian’s list, by my count we have:

Michael Reinoehl, a suspected killer shot by federal agents

Jorge Gomez, an armed protester shot by cops in Las Vegas

David McAtee, a restaurant owner shot by the National Guard in Louisville, KY

Sean Monterrosa, killed by cops in Vallejo who were investigating reports of looting

That’s four killings by police over the entire course of the protests.

What about violence against police? The only two on-duty cops killed during the protests were killed by the “Boogaloo Bois”, a rightist extremist group dedicated to the fomenting of civil war. Additionally, there was a 77-year-old retired ex-policeman named David Dorn who was killed in a pawn shop robbery in St. Louis. There were also a policeman shot in the head and paralyzed in Las Vegas during the protests, though the shooter was reported not to have participated in protests. There have also been at least four other policemen shot in connection with the protests, though none fatally.

That is a startlingly small amount of cop killings. You’d think, with 20 million people marching in the streets enraged against the cops, there would have been at least 1 policeman murdered by protesters somewhere in America. But there were none.

In other words, the Floyd protests were not a war of cops against protesters. Both sides indulged in more violence than they ought to have, but both showed remarkable restraint given the huge, dramatic, prolonged, historic, and highly acrimonious nature of the protests.

Let’s review the deadly incidents

So far I’ve been talking in terms of aggregate statistics. But given the small number of deadly incidents, we can review the list of killings for signs of a civil war between the Left and the Right.

As I see it, these can be classified into several categories:

Category 1: Random Crime

David Dorn (the retired ex-cop) killed in a pawn shop robbery)

Tyler Gerth, a reporter shot by a man with a history of mental illness while covering a protest

Victor Cazares Jr., killed while trying to protect a store in Chicago

Jose Gutierrez, killed by looters in Chicago

Category 2: Altercations during the protests

Lee Keltner, killed by a security guard for a local news crew after slapping the guard

Joseph Rosenbaum, shot by Rittenhouse

Anthony Huber, shot by Rittenhouse

James Scurlock, a protester shot in a confrontation with a bar owner

Jessica Doty-Whitaker, shot while arguing in the street

Calvin Horton Jr., killed by a store proprietor who claimed he was trying to loot the store

Category 3: Bizarre political killings

Antonio Mays Jr., killed by the “security forces” of the Seattle CHAZ (Capital Hill Autonomous Zone)

Horace Lorenzo Anderson Jr., killed in the CHAZ

David Patrick Underwood, killed in a Boogaloo attack

Damon Gutzwiller, killed in a Boogaloo attack

Category 4: Police killings

Michael Reinoehl, a suspected killer shot by federal agents

Jorge Gomez, an armed protester shot by cops in Las Vegas

David McAtee, a restaurant owner shot by the National Guard in Louisville, KY

Sean Monterrosa, killed by cops in Vallejo who were investigating reports of looting

Category 5: Right-Left political violence

Aaron Danielson, a Trump supporter shot during a counter-protest (probably by Michael Reinoehl)

Garrett Foster, an armed protester shot to death by a man who was attacking protesters with his car

Summer Taylor, a protester rammed by a car attack

Robert Forbes, a protester rammed by a car attack

Barry Perkins, a protester rammed by a car attack

Category 6: Accidental killings by protest violence

Secoriea Turner, an 8-year-old shot to death in Atlanta

A body found in a burned-out pawn shop in Minneapolis

Only five of the killings during the protests were the result of battles between adherents of pro-protest and anti-protest ideologies. Add in police killings, and the number rises to 9. Add in the 6 people killed in altercations and the 2 people killed by protester violence, and the number rises to 17. If you think of the Floyd protests as a war between Left and Right, then that war killed at maximum 17 people.

It’s notable that four people died (and several others were grievously injured) by political violence that had nothing to do with the Left-Right conflict that most people think about. All the on-duty cops killed during the protest were killed not by anti-police activists or protesters of any kind, but by a bizarre quasi-rightist sect called the Boogaloo movement, whose apparent goal was simply to foment chaos. And the trigger-happy so-called “security” forces of the anarchist CHAZ (who, anecdotally, were mostly White) ended up killing two innocent Black bystanders in defense of their bizarre failed social experiment.

This bizarre violence helps put the rest of the killings in context. The Floyd protests were a time of remarkable unrest, in which passions, tensions, and stress were running high. In those situations, in a violent, heavily-armed country like the U.S., a few people are going to end up killing each other. Sometimes those killings will be over the thing that the protest is about, but more often they’ll just be a result of general panic and chaos.

That’s a far cry from a civil war.

Looting is not political

Speaking of general panic and chaos, I should say a word about looting. Most of the violence that was reported during the Floyd protests consisted of people smashing store windows and making off with the goods. But as the recent spate of store robberies in the Bay Area demonstrates, raids on retail don’t need any kind of political motive.

Studies of looters generally find that they’re not the same people as protesters. Olga Khazan reported on this back during the protests. Sociologists generally find that looters are motivated by some combination of A) the desire to steal stuff, and B) a general frustration and sense of powerlessness. While the cops are distracted by protests, looters seize the opportunity to do what they’d never dare to do on a normal day. (This suggests, by the way, that cops should spend more time protecting stores during protests, and less time policing the protesters themselves.)

This is not to say looting and property damage are unimportant. Indeed, I think progressives ought to be more sympathetic to the destruction of property during the protests, much of which fell on people of color and on small businesspeople who weren’t insured. Property isn’t as important as life, but it is very important, and if you support the Floyd protests, you should also support helping those who were incidentally harmed by the chaos the protests created. But it just isn’t a civil war.

Why this is important

So why am I going to all this trouble to prove that the Floyd protests weren’t a civil war? The answer is that the danger of an actual, real civil war is hanging over us, right now. Republicans are gearing up to dispute the result of the 2024 presidential election if they lose, possibly even to the point of using their control of state legislatures to send slates of electors not chosen by the state’s popular vote. The result, if this happens, will be an unprecedented constitutional crisis, potentially leading to mass bloodshed. A recent Zogby poll found that a plurality of Americans believe a civil war is on the way.

Behind that conviction, I think, lies many people’s belief that America is already in a state of civil war — a war they think began in the summer of 2020. Talk to any conservative, and you’ll see that the Floyd protests loom large and terrifying in their cosmology. They may see election denial, election theft, or even organized violence as a response to those protests.

The closest parallel here is the Spanish Civil War. The nationalist Right, who started the war with a failed coup, believed that they were responding to the threat of revolutionary leftist violence. And their chief piece of evidence for that belief — the main event that scared them into overthrowing the state — was the Asturian miners’ strike of 1934. That strike seized control of a whole Spanish province and threatened to overthrow the central government, until it was finally crushed by the army. This scared many on the Right into believing that if they didn’t overthrow the government and seize control of the country themselves, the Left was bound to do it eventually.

For some people on the Right in the U.S., the Floyd protests play the role of the Asturian miners’ strike — a revolutionary leftist uprising that demonstrates a need for a rightist putsch in response. In fact, the two episodes are nothing alike — the miners’ strike was an explicit attempt to violently overthrow the government, in which thousands of people were killed. The Floyd protests were, by and large, a peaceful exercise of Americans’ constitutional right to protest against the brutality of local police forces, in which very few died and no military action was needed.

Making this distinction is important. Putting the Floyd protests in their proper political context means remembering the details, and realizing that the protests were simply an especially large version of stuff that happens in America all the time. By relentlessly repeating the truth that America isn’t in a civil war, we can hopefully calm tempers and passions and keep a real civil war from breaking out.

“Mostly peaceful”. Queue the chyron of cities burning. What a joke. Unsubscribing.

The role of the Proud Boys, Boogaloo Boys, and the police themselves in instigating violence, rioting, and vandalism has just been completely memory-holed, and appreciate that this article at least mentions that they played a role, but it needs more discussion.