The educated professional class is out of touch with America

Lesson #3 from Trump's victory.

I’ve been writing about the lessons that Democrats should take away from the big GOP victory in this week’s election. I’ve written about how identity politics is failing to attract Hispanic voters, and about how Dems cared too much about employment and not enough about inflation. The third big lesson, I think, is about class in America. The educated professional class is drifting away from the rest of the country, in terms of values, beliefs, and their information diet.

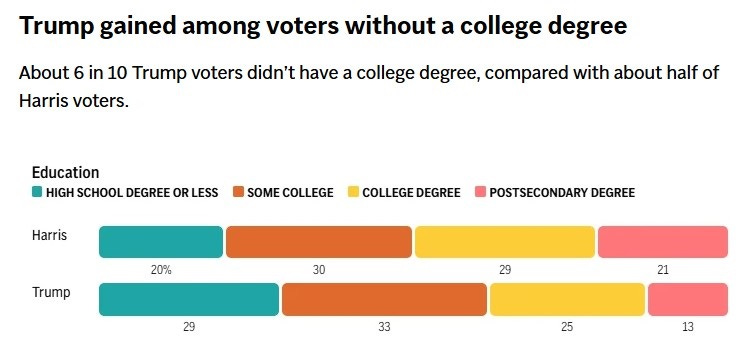

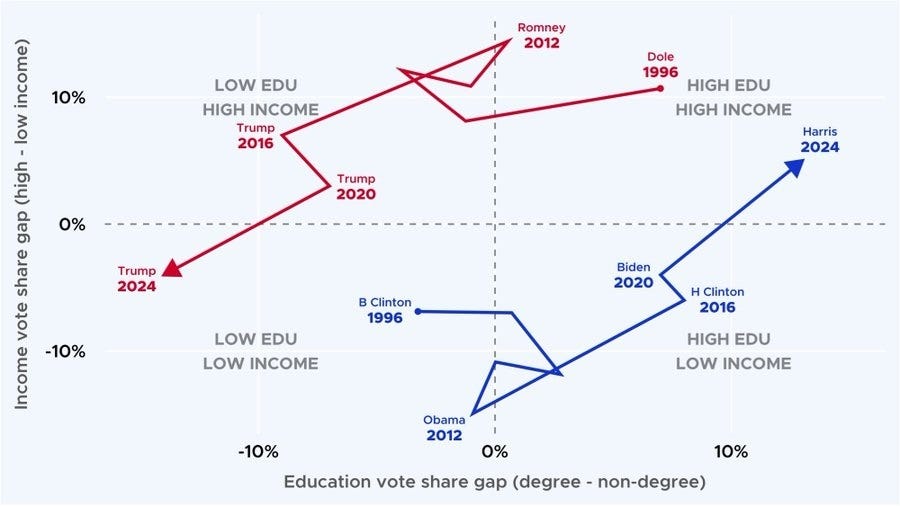

This election upended a lot of demographic trends that people had been very certain about only a few years ago. Trump seems to have produced a large-scale shift of Hispanic voters to the Republicans, and big cities swung harder toward the GOP than other areas. But there’s one key trend that this election didn’t reverse: education polarization. Trump was even more dominant among non-college voters than he was in the last two elections, while Harris won the highly educated by about as much as Biden did.

Over the years, the Democratic base has shifted decisively from the working class to the educated professional class:

This shift doomed Harris’ campaign, since people without college degrees outnumber their college-educated counterparts — in 2024, the latter were only 43% of the electorate.

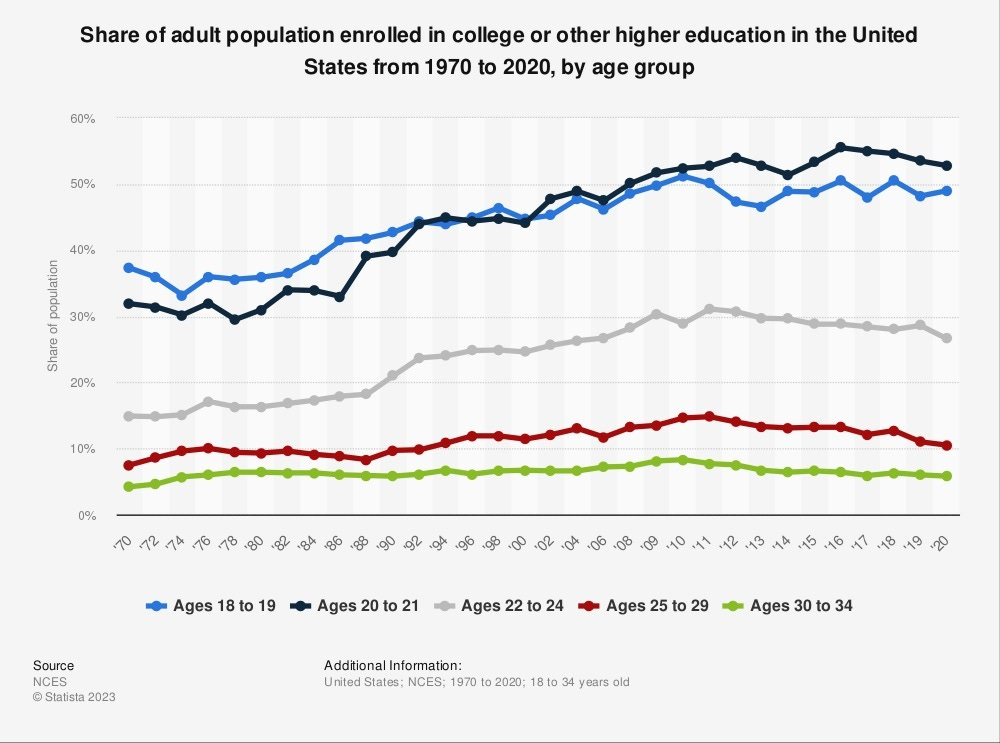

And this weakness looks likely to be a long-term problem. In the past, when college education was steadily increasing, it was easy to think that college-educated voters would own the future. But in recent years, the rate of college enrollment has plateaued and begun to fall:

And the number of new college graduates fell in 2022, even as America’s total population grew.

As for why fewer Americans are getting a college education, I wrote a post about this back in July:

The short version is that tuition soared even as the earnings boost from a college degree shrank substantially, making college a less attractive value proposition. A lot of this had to do with colleges themselves boosting spending on administrators and facilities, and having to charge students more to pay for it.

If universities cut costs, cut tuition, and raised their value proposition, we could see enrollment rise again at some point, but I wouldn’t bet on that happening soon. Meanwhile, socialists’ plan for universal free college is dead on arrival; even Biden’s generous new student loan repayment provisions might prove to be temporary, since the fiscal cost is so huge. So a wave of taxpayer cash is not going to restore the trend of rising educational attainment.

In other words, Democrats’ education problem is here to stay. Unless Dems can figure out how to win back those non-college voters, they’re likely to be at a huge electoral disadvantage for the foreseeable future.

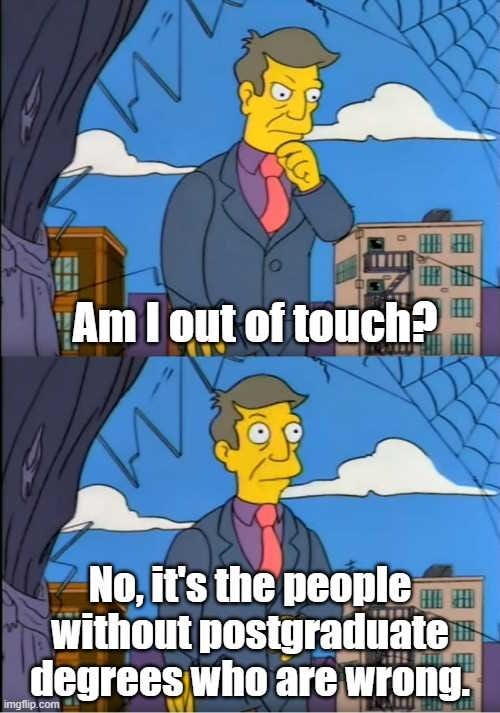

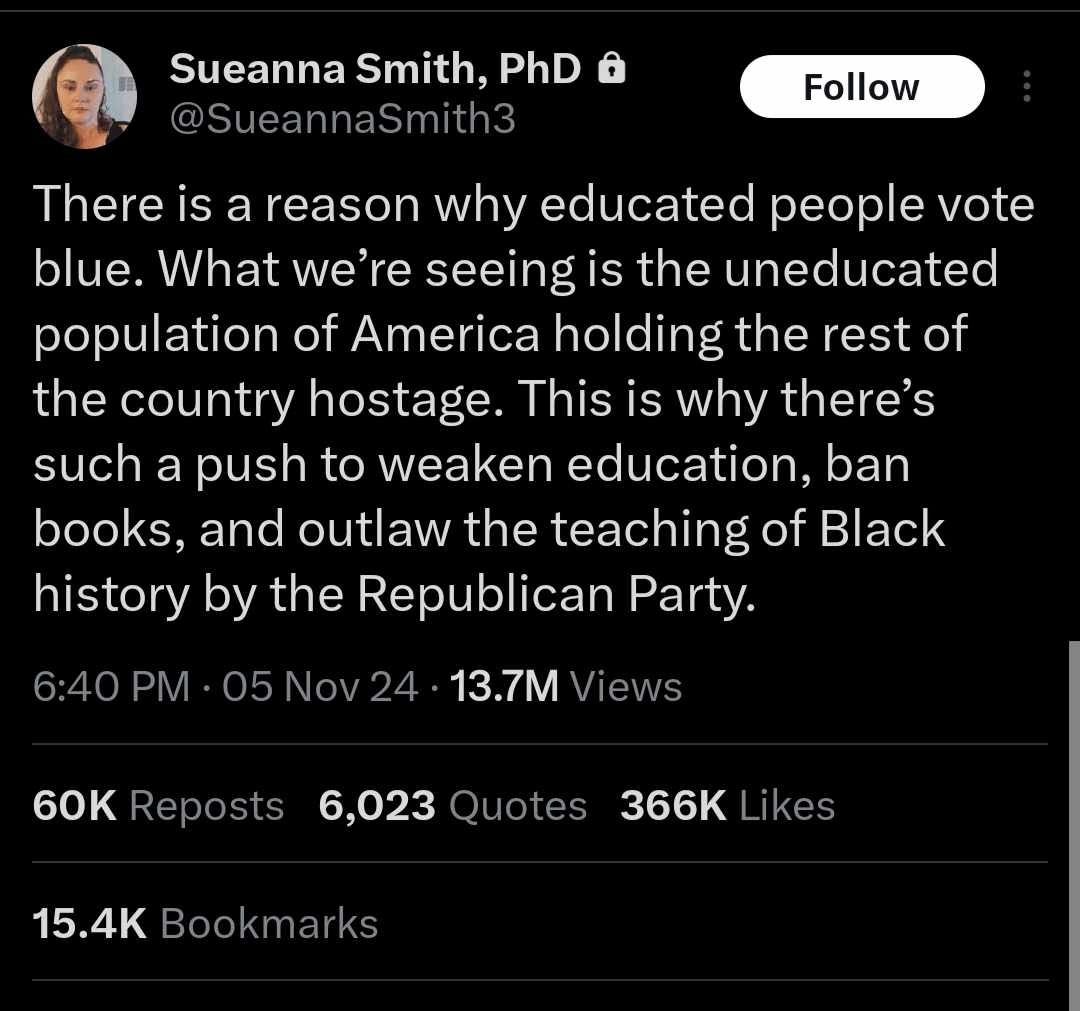

But winning back those voters would require the educated professional types who make up the backbone of the Democratic base and the progressive movement to figure out how to connect rhetorically with the less-educated masses, addressing their concerns, speaking to their values, and just speaking their language in general. And although it’s too early to tell, many of the reactions I’m seeing on social media are, to put it mildly, very unencouraging:

Obviously these are extreme examples, but in general it seems to me that the educated professional class has simply grown apart from the rest of the country over the past few decades.

A disconnect on problems

The most important disconnect between educated professionals and the rest of America is about the problems they face on a day-to-day basis. Practically every problem that Trump voters cited is something that hits the working class harder than the professional class.

About a year ago, I found a really good place to get a haircut. The hairstylist, a Vietnamese immigrant woman in her 50s, was complaining about rampant theft from small businesses in the neighborhood. She said that if thieves stole less than $950, they wouldn’t even be arrested or prosecuted, creating an incentive for constant theft.

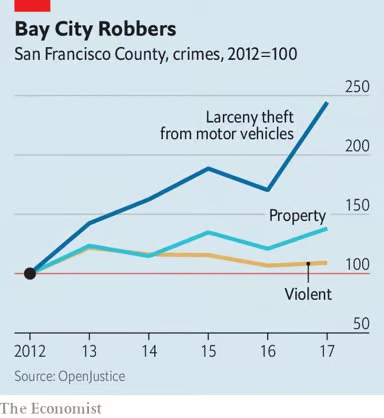

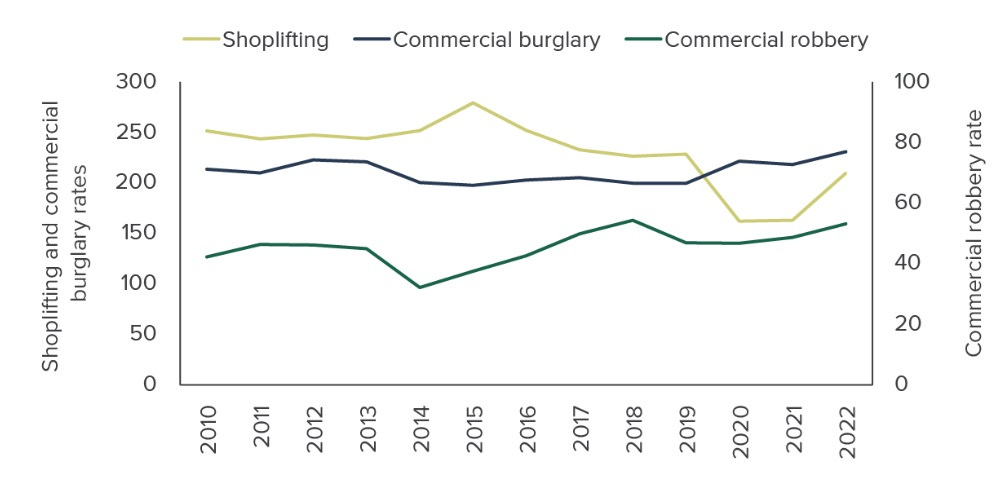

In fact, stealing less than $950 was still a crime, but there was a plebiscite in 2014 called Proposition 47 that changed it from a felony to a misdemeanor. (Prop 47 was mostly repealed this year, when California voters passed another ballot measure called Prop 36.) I’m not sure how big of a factor Prop 47 was, but for whatever reason, property crime in San Francisco did rise quite a lot in the late 2010s:

This mirrored a more general rise across the state1:

I am an educated professional, not a small local businessperson. I had heard about the big wave of car break-ins in San Francisco, but it took me a very long time to realize how common retail theft had become. To me, the wave of smash-and-grab attacks in the Bay Area was a sign of urban disorder and decay, and a force causing a bunch of downtown stores to close.

But to someone who owns a hair salon that gets robbed, or a convenience store that gets looted, that’s their livelihood. That could be their child’s ticket to college, or their ability to get the pipes fixed at their house, or their chance to get their car fixed. As an educated professional, I’m simply much less exposed to robbery and theft.

And on top of that, I’m an urban educated professional. Those who live out in the fancy suburbs are even more disconnected from the crime wave that afflicted America in 2020 and 2021. It’s lower-earning people in cities or poorer neighborhoods who bore the brunt of the explosion of disorder that followed in the wake of the Floyd protests.2

Stuff like “defund the police” is a luxury of the rich and mobile — i.e., of the educated professional class. It’s lower-income Americans and small business owners who need the police the most.

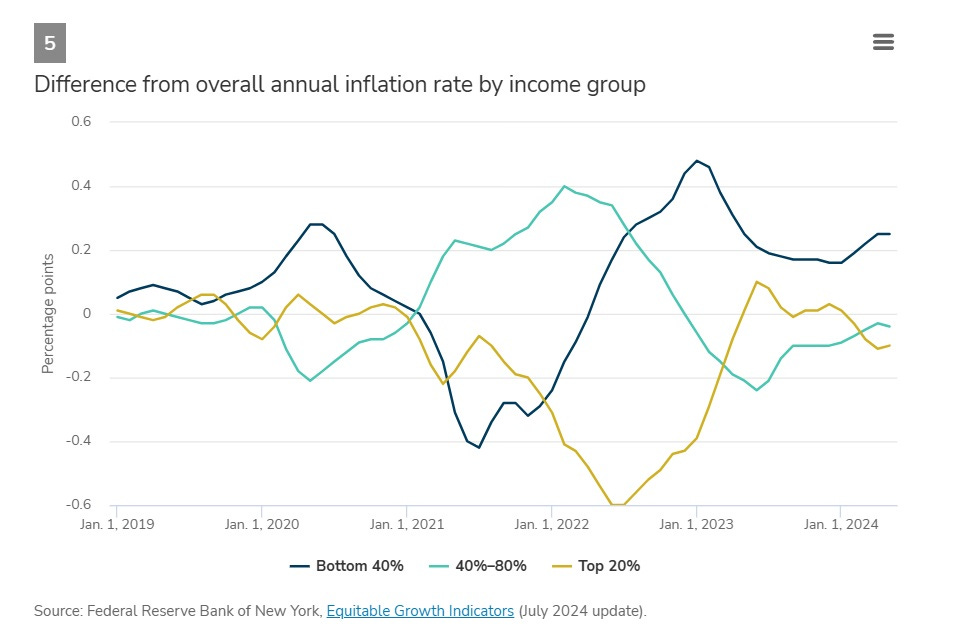

How about inflation? When defending the Biden economy, I often point out that real wages for people in the lower part of the distribution increased faster. That’s adjusted for inflation, but it’s adjusted for the overall state-level inflation rate. In fact, as the Minneapolis Fed’s Jeff Horwich explains, people who make less money have faced higher price increases since 2021, for two reasons. First, the things that lower-income and middle-income people spend a larger percent of their income on — especially housing — tended to go up in price a bit more:

The second reason is pretty obvious: Having less money makes drops in purchasing power harder to bear. If my cost of living went up by 10%, it would be a minor annoyance; to a working-class person that could very well be ruinous. No wonder lower-income people tend to notice price changes more:

So while educated professionals like myself were able to put the post-pandemic inflation behind us fairly quickly after it subsided in 2023, regular Americans probably felt a more lingering hurt.

How about the wave of asylum seekers that flooded across the border in the Biden years? Lower-skilled immigrants don’t actually tend to reduce wages for native-born working-class Americans. But a big part of the reason they don’t reduce wages is that native-born people respond to increased immigration by going back to school and climbing the skill ladder. That takes time and money.

Also, low-skilled immigrants directly compete with less-educated and lower-earning Americans for housing. Asylum seekers tend to be poor, meaning they will try to get apartments and houses in lower-income neighborhoods. The effect on local rents in those neighborhoods, and for those types of housing, will be greater than the overall citywide or statewide effect. Rent will go up for the American working class, differentially affecting their purchasing power in ways that don’t get captured by state-level or national statistics.

So although Biden did beat inflation, crime did go down, and Biden did eventually crack down on the border, I can understand why the traumas that working-class Americans had to suffer in 2020-2022 couldn’t be expunged just by some encouraging charts. And the fact that educated professionals were much more insulated from the disruptions of the pandemic and from Biden’s missteps in 2021 mean that they didn’t necessarily even see the need to acknowledge how hard these had been on everyone else.

This disconnect probably ended up alienating people without college degrees. Not only did it cause many progressives to support deeply unpopular things like “defund the police” on social media, but Democratic politicians who became used to talking to their educated progressive base probably got a distorted idea of what was troubling the rest of America.

An information disconnect

I was taking an Uber with a friend a couple of weeks ago, and the driver went on a gigantic rant about how inflation is out of control, vaccines are ineffective and are causing all kinds of massive health problems, there are no jobs anymore, and so on. Listening to his rant drove home the fact that there are huge segments of the American populace that I’m just completely out of touch with.

Almost all of what he said was factually wrong, of course. Inflation is back down to a low level, and has been for years now. Employment is near all-time highs. Vaccines are safe and effective, and so on. But the fact that he believed in all of this stuff is a sign that there’s an information ecosystem out there that’s totally separate from the world of blogs and Washington Post articles and nerdy podcasts and Econ Twitter that comprises my own information diet.

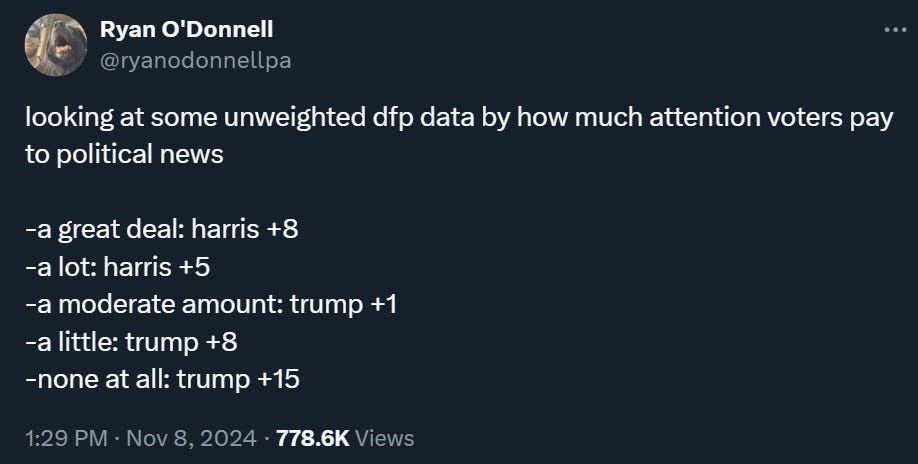

In fact, this information disconnect is probably one reason why Trump won. Voters who knew about the positive data that I know about — and which I frequently talked about on this blog — went very strongly for Harris, while voters who had the same misapprehensions as my Uber driver went pretty strongly for Trump:

Now, people may simply be bullshitting on these polls — there’s research that shows that when you pay people to get these facts right, they tend to get them right. Saying “inflation is still high” might just be a way of saying “I like Trump”.

Also, note that all four of these questions are specifically phrased in such a way that the correct answer says something positive about Joe Biden’s tenure in office. If the questions had been things like “Overall, murder rates were higher under Biden than under Trump (True)”, or “Inflation in the U.S. since 2021 has been the highest of any four-year period since the 1970s (True)”, or “Since 2021, unauthorized border crossings have been higher than at any point since the early 2000s (True)”, it might have been Democrats getting the facts wrong instead of Republicans. (We’ll never know, of course, but Democrats do tend to show partisan bias on economic surveys.)

But it also seems likely that many of these less-educated Trump voters just don’t get nearly as much information about politics, economics, and public affairs. Highly educated folks consume a lot more news in general. And people who consume a lot more political news tended to vote for Harris:

And when they do consume news, it’s likely to be from different sources. Many election postmortems have focused on the fact that Joe Rogan, a popular podcast host with many blue-collar fans, interviewed both Donald Trump and JD Vance during the campaign, but not Kamala Harris or Tim Walz. Joe Rogan’s podcast has 18 million subscribers. In comparison, Fox News, the most popular cable news network, has somewhere around 2 million primetime viewers.3 Meanwhile, Barstool Sports, another news outlet that’s popular with blue-collar types, went solidly for Trump and reportedly refused Harris’ offer for an interview.

In other words, Democrats are still doing a good job of getting their message to educated Americans who consume lots of political news, but are increasingly failing to reach the non-college masses. That’s why listening to an Uber driver talk about politics can seem like meeting someone from another universe.

This is not to say that educated progressives get the facts right, while blue-collar conservatives get them wrong. In fact, highly educated progressives can talk themselves into believing some absolutely insane things. During the summer of 2020, a lawyer friend insisted to me that the institution of police grew out of the institution of American slavery (obviously wrong, since police emerged independently all over the world). A number of progressives also asserted to me that police don’t reduce crime (false). The oft-repeated progressive claim that slaves built America is also obviously false, since slaves were less than 10% of the population. A few educated progressives even fiercely defend intentional fabrication of results in the social sciences, on political grounds.

But whatever the various myths are on the left and right, they are different myths. And because educated professionals swim in entirely different information ecosystems, they have little clue how to reach the masses and tell their side of the story.4

Why did the class disconnect come about, and how can we reduce it?

“Her belly may be full, but her spirit will be empty.” — Jean-Luc Picard

The educated professional class has been growing apart from America’s other social classes for decades now. Part of this was due to the big shift in the U.S. economy — the rise of knowledge industries like IT, finance, biopharma, and business services pulled America’s talented people to coastal metros and college towns. As the economist Enrico Moretti showed in his excellent book The New Geography of Jobs, a city’s human capital — i.e., how many educated professionals live there — became the best predictor not only of economic success, but also various measures of public health and well-being.

For those with the talent to escape the bleakness of their hometowns, big cities like New York, San Francisco, and Minneapolis — or college towns like Ann Arbor, Madison, and Berkeley — became magical playgrounds, full of great restaurants and shops and bars, other educated professionals to date and marry, and plenty of money to be made. I was one of the people who made that escape.

But what happened to the places the talented people left behind? Bereft of their talent in an age when talent equals money, they stagnated economically — counties that voted for Biden in 2020 represented just over half of the electorate, but 70% of America’s total GDP. And without as many talented people to be local doctors, teachers, etc., those places saw their health deteriorate — drug use and obesity ran rampant. Even the well-documented decline of marriage among the less-educated could be partially due to talented professionals fleeing the area — without as many visible examples of economically successful educated people getting married and staying married and raising kids in two-parent families, some working-class people in left-behind towns may have simply abandoned the practice.

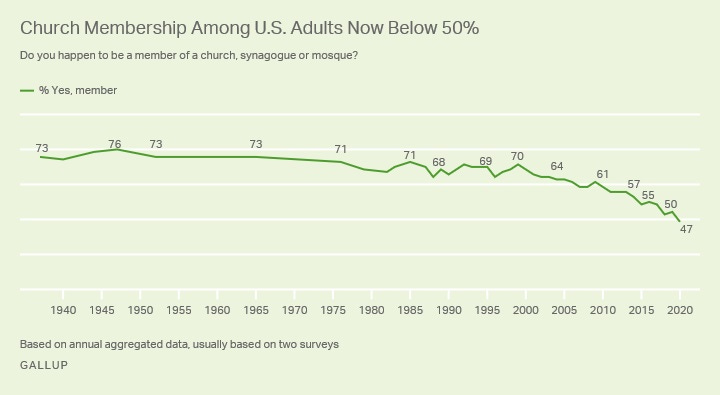

This is the first reason for the disconnect. The second, I think, was institutional. In earlier times, there were a number of institutions that regularly brought people together across social classes — the three main examples being churches, businesses, and the military. But after Vietnam, the U.S. Military shifted from a mass-participatory conscript force to an elite professional volunteer force. Business became increasingly fragmented, with much blue-collar work and low-level service work outsourced or automated. And church membership has declined5 in America, possibly as a result of the internet:

Combine this with the de-localization of American social life due to the car and the internet, and you have a recipe for extreme sorting. As Tyler Cowen writes in his book The Complacent Class, Americans have become increasingly expert at sorting themselves according to education, income, and other characteristics.

There was one public institution that managed to retain its broad functionality over this time period: College. American universities tried hard to recruit and mix people of diverse backgrounds, teach them healthy personal and social habits, and provide them with a rich community life that could be a model for their later adult communities. And to a large degree, this worked.

But it only worked for 40% of the population! The majority of Americans lacked the talent, the study habits, the inclination, the time, or (eventually) the money to get that four-year degree. So for that lucky 40%, colleges were church and army and work team all in one — an acceptable substitute for the tight-knit villages that the modern economy of the car and the internet had destroyed.

For the rest of the country there was nothing. There were daytime TV and televangelists and methamphetamine and conspiracy theories. There were strip-malls and NASCAR and hip-hop and Marvel movies. There were Fox News and Rush Limbaugh and Michael Savage. There was plenty of cheap land, big houses, cheap cars, and jobs in the vast service sector. But their upper caste had fled them for the playgrounds of college and the big city and the Google cafeteria.

But they were still part of the same country as the educated professionals. And so they all still voted in the same elections. So one day Donald Trump came along, and the classes were reunited by the institution of electoral democracy, in a very unpleasant and painful way.

After this crushing defeat, many educated progressives will turn to the idea of Bernie Sanders-style “class” politics as an alternative to the identity politics that failed so spectacularly. But this won’t work either.

First of all, Bernie himself underperformed Kamala Harris in this year’s election. Second, and more importantly, Biden has been the most pro-labor, pro-union President in many decades, and it availed the Democrats nothing. Biden raised overtime pay, strengthened unions with various new laws, revived factory construction with industrial policy, mandated the hiring of union workforces for federal contracts, became the first President to walk a picket line, funded vocational education and apprenticeships, banned noncompete clauses, and took dozens of other actions in support of the blue-collar working class.

Wages rose strongly for the working class, and inequality fell. Biden also enacted a lot of Bernie-style policies — canceling student debt, passing a huge climate bill, and increasing subsidies for health care.

And none of it helped Kamala Harris. The Teamsters union withheld their endorsement. The East Coast dockworkers’ union threatened a crippling strike just weeks before the election. All across the nation, steelworkers and other blue-collar union workers defied their leaders and organized in support of Donald Trump. Harris did win a slim majority of the union vote, but this probably came mostly from educated professional types, especially public unions.

The fact is, America just isn’t the industrial society it was in the 1950s. The broad blue-collar manufacturing laborer class is a thing of the past, and the fragments of that class that remain are often more focused on sociocultural issues than on pure pocketbook concerns. Most of the American non-college populace are non-unionized suburban service workers with no real class consciousness.

America, fundamentally, is an incredibly rich country with a sick society. We have higher consumption by far than people in any other country on the planet, and yet by and large, except for the few people who were lucky enough to receive the blessings of community and health from our one remaining functional institution, we’re a bunch of unhealthy socially isolated drug addicts.

As for the solution to all this, I don’t have an easy fix. In the long run our country needs to build new inclusive institutions — places where society’s classes mingle and cooperate. I don’t know what those can be, though of course I’ll think about the problem. But it will take a long time. Obviously, YIMBY policies that allow working-class people to live in big cities will help a bit, by putting the various classes in physical proximity, but without integrating institutions the effect will be marginal.

Nor do the educated right-wing professionals in the tech industry understand their new working-class political allies any better than the progressives do. Beyond helping to elect Donald Trump and annoy educated progressives, they don’t really have any plans to help those who lack the talent to work at SpaceX.

In the short term, what Democrats can do is to realize the extent of the problem, and begin doing everything they can to explore the culture and the information ecosystem of Americans who didn’t go to college. Get interviewed on Rogan and Barstool Sports and wherever, but don’t just get interviewed — immerse yourself in the culture. Don’t get your information about regular Americans from the activist groups who knock on your staffers’ doors, or from 20-something socialists who spout stale Marxist theory. Go meet them, find out what they care about, and think about how to give it to them.

Fixing America’s great class disconnect will take a long time, but there’s no better time to start.

Shoplifting shows a decrease on this chart, but this is probably due to a drop in reporting rates. When you don’t think the police will do anything about shoplifting, you don’t tend to tell them when it happens, and it doesn’t get recorded.

And it was disproportionately Hispanic-owned, Asian-owned, and Black-owned small businesses that got looted that summer and afterwards. Small wonder that nonwhite voters shifted toward Trump!

All Things Considered, the most popular NPR program, has 14.7 million weekly listeners. Sean Hannity has about 14 million.

This is obviously true for me as well, of course. I don’t know for sure, but my bet is that almost all of my audience is college-educated.

Note that regular church attendance is actually pretty stable. It turns out that a lot of church members lie about going to church regularly, which you can see when you track their cell phones. But the people who only go to church services once in a while are still probably involved with the institution, which puts them in at least occasional contact with a bunch of people from other social classes.

Focus group of one here. As a wealthy person, inflation was less of an issue for me because I had so many assets that shot up in value. Wealth effect totally overshadowed the inflation impact, especially when my biggest expense was a mortgage I locked in around 3%.

Not trying to brag, just giving the mechanics of why inflation maybe wasn't so stressful for richer Americans. Who actually knew the prices of eggs and milk anyhow? Groceries aren't that big a share of my monthly spending.

National Service! If someone can explain why there is so little discussion of national service (non military, non mandatory technically but practically mandatory eg tied to high school graduation requirement etc) as a new social glue institution, I would appreciate it.