This post does not reflect the views of Chris Best. He is listed as an author because he is included in the video chat portion.

The other day I had a chat with Chris Best, the CEO of Substack, which you can watch above. We talked about the future of the media, focusing on how people share and consume news and analysis. We agreed that X (formerly Twitter) has lost much of its usefulness as the nation’s one-stop-shop for breaking news and discussion, and we discussed some ideas for how Substack might take on that role.

Shortly after we recorded our conversation, X suffered a partial outage. That wasn’t too unusual — outages happen from time to time. What was odd about this time, though, was that I didn’t even notice the outage until after it was already over. X, the app that once consumed much of my waking life, and which enabled my career as an opinion writer for over a decade, has become so unimportant to my information diet that I didn’t even notice its absence.

An important shift is underway in America’s media landscape. Usually, discussions about the media focus either on local newspapers, or on corporate legacy media like the New York Times.1 But during the 2010s, social media — and in particular, the single platform of Twitter — became more important to America’s national information diet than any content creator.

I still remember when I first got on Twitter in 2011 (years later than I should have). Hearing that it was a “microblogging” site, I logged on expecting to find something akin to a smaller version of the blogs I knew; instead, what I found was utter chaos. The feed was a neverending mix of every conceivable kind of content — jokes, news reports, memes, shower thoughts, arguments, links to blog posts, insults, and more. More than Facebook or YouTube or any other social media site, it felt like Twitter opened up the entire world and poured it down your throat — the only comparable event was the creation of the Web itself.

Simply bringing some semblance of order to that firehose feed took years. By then, Twitter had cemented itself as the nation’s town square — it took a hundred million discussions that had been fragmented on forums and chats and comment sections and aggregated all of them into one place. On Twitter it felt like I could meet anyone, get attention from anyone, or be part of any important world event. As an information source it was unrivaled — if I walked down the street and saw smoke, I could do a quick Twitter search and find out within minutes if it was a terrorist attack or a house fire.2

Twitter’s unbeatable advantage over every other discussion platform was its radical openness. On Twitter you could talk directly and permissionlessly to any person in the entire network; if you tagged them, you’d show up in their notifications. Anyone could jump into anybody else’s discussion without permission, and no one had the power to kick them out. There were no walls or separators between communities or conversations. There was no moderation, no filter, no privacy, no built-in hierarchy. It felt like one step closer to a global hive mind.

I believe we have not yet reckoned with the degree to which the unrest of the 2010s was the direct result of this one single discussion platform. A nation that had spent decades dealing with our differences by spreading out and sorting ourselves into like-minded enclaves was suddenly thrown into one small room with each other — and like the characters in Sartre’s No Exit, we found the results rather hellish.

Researchers found that Twitter’s retweet system amplified and rewarded the most sadistic and opportunistic agitators in our society, whose desire to foment social chaos had previously been frustrated by their geographic isolation and their exclusion from traditional media. But research also showed that even normal people had the incentive to act toxic — if you could dunk on someone or make them the “main character”, the platform rewarded you with social status in the form of followers and likes. Cancel culture itself was almost entirely a creature of Twitter — it was fear of being yelled at on Twitter that drove companies and other organizations to accede to the will of mobs demanding that certain of their employees be punished.

But for all its chaotic influence, Twitter was an indispensable tool. It offered conversations about public affairs that were richer, more informed, and more interesting than almost any forum or blog or chat group. It offered unrivaled opportunities to meet people — including famous people — and network. For bloggers, it was the most important way to promote your content. For journalists, it became the universal assignment desk — there was the sense that if something wasn’t happening on Twitter, it wasn’t worth reporting on.

During events like elections, protests, wars, and disasters, Twitter was by far the fastest and best source of up-to-the-second information, because everyone was competing to earn social status on the platform by reporting anything that happened in their vicinity. Twitter was the nation’s water cooler — it let you take the measure of the zeitgeist, gauging the national mood and identifying the most important topics of discussion. Professors would teach you things on Twitter. Young people would shower you with jokes and memes. It was a note-taking app and a soapbox and a chat app and a repository for your shower thoughts. It was the most addicting and absorbing and all-consuming piece of software I’ve ever used.

And now it’s dying.

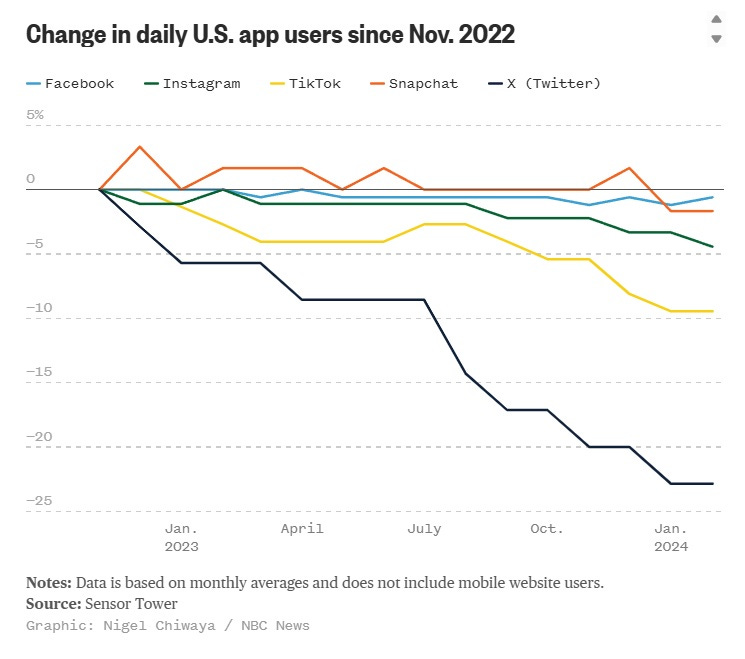

There’s plenty of data showing a decline in Twitter usage since Elon Musk took over the platform and renamed it “X”. For example:

X, formerly known as Twitter, experienced a 30% drop in usage from 2023 to 2024, according to a study from Edison Research…The data, which is part of a larger study conducted by Edison, said 27% of the total population in the U.S. reported using X in 2022 and 2023, a figure that has decreased to 19% in 2024.

Or:

And:

According to data from SimilarWeb…[I]n the broader leadup to the [2024] elections, X actually continuously shed daily active users. In fact, for the entire month of October, X saw a drop in anywhere from 300,000 to 2.6 million daily active users in the U.S. each day. Since early October, daily active U.S. users have fallen from 32.3 million to 29.6 million, a drop of 8.4 percent…[A]ccording to analysts, it appears like X will continue its decline in 2025.

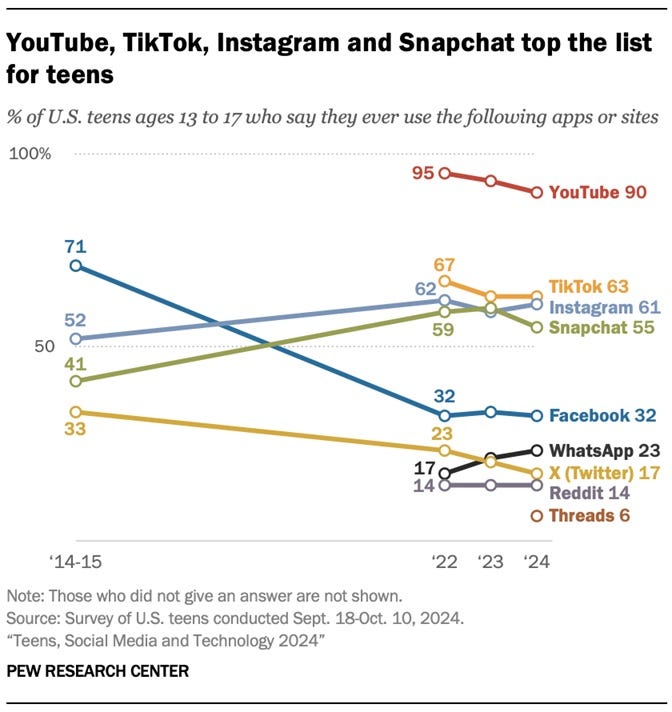

The standard narrative is that Musk himself drove the exodus, with his right-wing politics, lax moderation standards, platform changes, and constant personal antics. But while that’s part of the story, Twitter’s decline started long before Elon took over. By 2022, the percentage of teens who used Twitter declined from a third in the mid-2010s to under a quarter:

As young people go, so goes the platform. The cultural vitality that I enjoyed in Twitter’s early days — the jokes, the memes, the slices of daily life — gradually vanished after around 2014. I’m not sure why this happened. It may be because the platform’s tone turned darker and more aggressive after the invention of the quote-tweet. It may be because people learned the hard way that jotting down your shower thoughts on the most open of all platforms could lead to dire personal consequences if the wrong mob happened to see your tweet and go after it.

Or it may simply be that the platform’s format was played out, and that young people moved on to something newer and more interesting, as they tend to do. But either way, the result was a generation that grew up viewing Twitter as a niche community rather than as the global “town square”. The site gradually became MySpace for Millennials.

In any case, the drop in Twitter users won’t necessarily hurt Musk, who recently had his AI company xAI buy X for somewhere in the ballpark of the same price he originally paid for the platform. And the acquisition may even be worth it — xAI may be able to get its money back from the repository of training data that X already possesses. But fewer users degrades the network effects that make a platform like Twitter important. Metcalfe’s Law works both ways — as the size of a network drops, the biggest losses in value come the earliest.

X has many core use cases, but each of these is becoming weaker by the day. It’s no longer the place for intelligent conversation — many of the smartest users have left the platform, so that replies are dominated by activists, trolls, and bored people tossing off rote statements as they wander by. And bots, of course — lots and lots of bots.

The user exodus has also made X much less useful for gauging the national mood — or even seeing what the country is chattering about today. The fact that the decline is concentrated among particular groups — progressives, the young, minorities, etc. — means that the platform is less representative of the country. That, in turn, makes X less valuable to journalists as their “assignment desk”, because plenty of important and relevant things just aren’t getting discussed on the platform.

X is still useful as a messaging app — many of the connections forged in Twitter’s heyday are still active, and there are plenty of people I only know how to contact through X’s direct messages. But as those people check their X accounts less and less, the messaging function is slowly degrading as well.

Musk also made two key changes to the platform that have undermined its former use cases. In early 2023, X started defaulting its users to a “For You” tab that shows a TikTok-like algorithmically generated feed, instead of a feed created by the people you follow. You can toggle over to the old-style “Following” feed, but lots of people don’t. Second, Musk deprecated external links — any tweets that link to articles, videos, or other websites outside the platform are suppressed in the “For You” feed.

These changes have made X much less useful as an aggregator of interesting news and information from around the internet. People still post links, but they put them in follow-up tweets, so that what you mainly see are the initial tweets — simply paragraphs of original text with no link. This also makes X a much worse place to promote your own work.

But perhaps most crucially, these changes are a big part of why X is no longer the place to get breaking news. During the recent conflict between India and Pakistan, it was actually very difficult to find reliable timely information on X; instead, I found myself going back to the real-time update pages on CNN and other traditional content websites, and being more satisfied with what I found there.

I think it’s actually pretty interesting and subtle to understand why X is less useful for breaking news. In the old days of Twitter, there was a social incentive for everyone on the platform to A) report in real time on anything that was happening around them, and B) boost other people’s real-time reports. Social media is basically a game where people try to gain status, and on Twitter you could get attention, follows, and likes by being a source that other people read in order to stay apprised of fast-breaking events. So everyone did it.

Now that incentive is eroding. The new algorithmic feeds won’t necessarily show people news about new events; instead, it often tends to display tweets about topics they’ve demonstrated interest about in the past. The deprecation of external links means that if you share a source for your breaking news, your tweet will be suppressed; therefore most factual, well-informed tweets about a fast-breaking event will look no different than random rants. And in general, X’s shrinking user base and diminishing levels of engagement mean fewer new followers to capture.3

As X users lose interest in reporting anything and everything that goes on around them (and boosting each other’s reports), the platform’s core function disintegrates — it’s no longer the first place you go to get breaking news. More than any other reason, that’s why I personally have been spending a lot less time on X recently.

But if X is no longer the place for breaking news, that presents other platforms with the chance to step up and fill that role. I’m sure this is possible — a world where 2000s-era update pages on www.cnn.com are the best we can ever do for breaking news, even in the age of social media and AI, sounds wildly unrealistic.

One possible contender is Substack. This platform has already become the best place for analysis of news, having resurrected and supercharged the blogosphere. Why not breaking news too?

In fact, this is the topic of my video chat with Chris Best at the top of this post. Our basic idea is that while Substack probably can’t replicate the “citizen journalist” magic of 2010s-era Twitter, it probably can set up a new kind of blog dedicated to real-time breaking news updates — indie versions of the CNN real-time update pages. And Substack can probably use its superior distribution tools — daily email digests, the Twitter-like Substack Notes tool, and maybe some new tools for aggregating breaking-news feeds — to do much better than the legacy media.

So that’s the basic idea. It wouldn’t get everyone in the world involved in reporting, like the old Twitter briefly did. But it could gather, amplify, and aggregate a whole bunch of on-the-ground reporters and human news aggregators. That might be the next best thing — and unlike the ephemeral magic of old Twitter, a Substack-style approach to breaking news might be sustainable in the long term.

In any case, I think the replacement of Twitter/X by Substack and other more purpose-built tools will be a good thing for society. As I always say, the internet wants to be fragmented; having one single town square doesn’t work in the physical world, and it doesn’t make sense in the digital world either. All of America (and much of the rest of the world) came together in one place in the 2010s, and that one place was Twitter. But with discussion now shattered into a kaleidoscope of Discord channels, group chats, subreddits, and smaller Twitter-like services like Bluesky, Mastodon, Substack Notes, and Threads, we have a chance to be individuals again — liberated from the hive mind that was trying to absorb us.

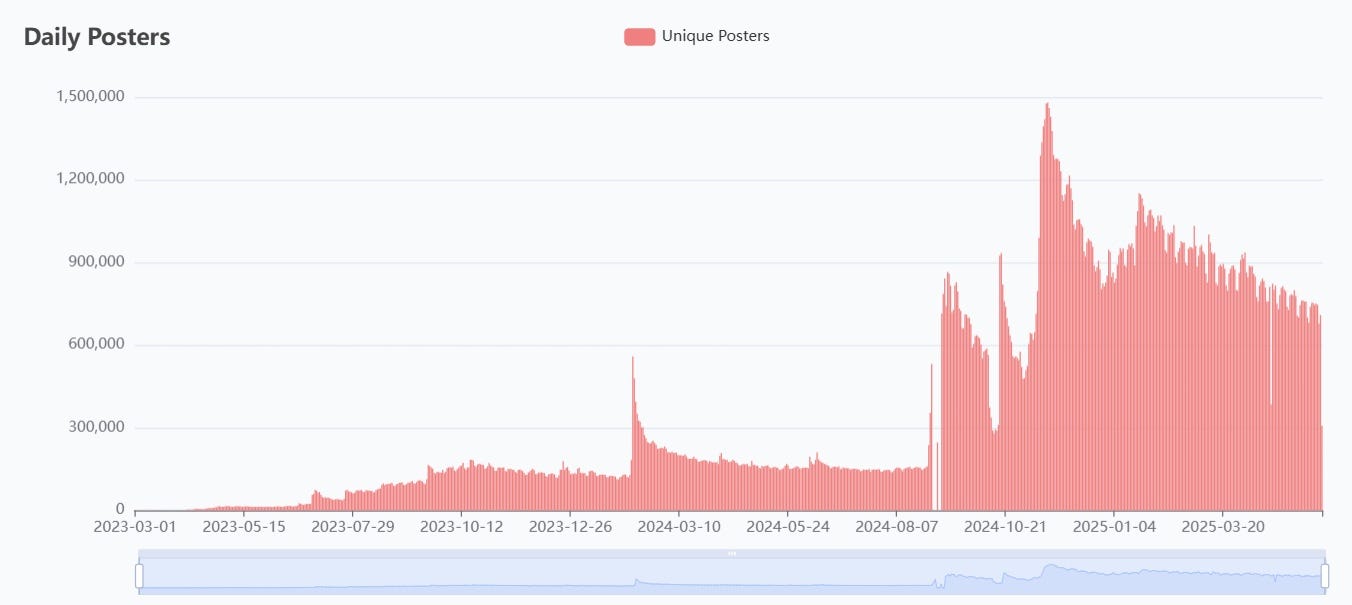

Nor do I expect any of the Baby Twitters to replicate what existed in 2018. I’m glad Bluesky exists, but I don’t think it’s going to conquer the world and become our one single town square:

Instead, what I think is happening is that people are realizing that this kind of radically open discussion app is not actually that great of a way to participate in the internet. It had a surprisingly huge number of advantages, and made some magic in its day, but it’s just too susceptible to bad actors. Some people will still enjoy the dunk apps, but a lot of people will filter away to more private discussions, and to calmer, less performative analysis on platforms like Substack.

The Age of Twitter destroyed the old age of legacy media so fast that the world almost missed it happening. Now that age looks to be ending, before we even understood what it meant. Fortunately, I’m optimistic that the next thing will be better.

In the latter case, this is probably because many of the people involved in those discussions write for those same publications.

Usually it was a house fire, but one time in Paris it was a terrorist attack.

In fact, as user numbers plateaued and follower graphs became ossified, doing anything for clout was always going to be less rewarding than in the past.