I did another Substack Live interview, this time with Patrick Collison of Stripe! In my previous one, it was basically me interviewing Paul Krugman; this time, it was more Patrick interviewing me. As usual, there’s a transcript available at the top of the post or at the side of the video. I’ll provide a summary below.

In the meantime, here are some podcasts! I did an interview with ChinaTalk’s Lily Ottinger when I was in Taiwan, about Trump, the new Tech Right, and what they mean for the fate of Asia. Check it out:

I also have two episodes of Econ 102! In one of them, I debate Scott Sumner on industrial policy. He came at the issue from a very libertarian point of view, while I came at it from a standpoint of national security:

I also have another Econ 102 episode in which I did a bunch of Q&A:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. Patrick Collison interviews me

Patrick gave me a bunch of interesting rapid-fire questions, and I tried to give him a bunch of rapid-fire answers.

First, Patrick asked me why U.S. labor productivity has grown almost uniquely fast among rich countries since 1990. I tried to give a theory, but in fact we just had the data wrong. U.S. labor productivity growth has actually been pretty average for a rich country since 1990:

We’ve done better since 2007, though Australia still does beat us:

It’s only since 2019 or so that America has clearly done better than the rest of the pack:

The most plausible explanation for America’s outperformance, I think, is labor reallocation; there has been a giant reshuffling of jobs in America that I don’t think has been mirrored in other rich nations, and this has led to improved productivity. The fact that the U.S. relies on bond markets while most other countries rely on bank lending may have contributed to this allocative advantage; banks often tend to keep companies on life support.

I also think America’s large domestic market probably has something to do with it, since this has probably allowed us to capture high-value industry clusters like the software cluster. Europe and the rich countries of East Asia are just too fragmented. China is our only real rival in terms of market size; Patrick and I had wanted to talk about U.S.-China competition, but we ended up not having time.

Patrick then asked me about the future of liberalism in America. I argued that folks like Matt Yglesias, Ezra Klein, and myself would fail to reform progressivism in the short term (as some have asked us to), but that we might be able to come up with ideas that would help build a new liberalism ten years from now. Some of the core ideas, I argued, would probably be:

patriotism

a focus on the well-being of the American middle class

abundance

reindustrialization

government effectiveness and increased state capacity

a new welfarism for uplifting the poor

Patrick asked me about what I thought the effects of humanoid robots on the economy would be, and I argued that while robots in general will be incredibly important, humanoid robots will continue to have very different capabilities from humans for the foreseeable future.

Patrick’s next question was about YIMBYism and aesthetics. He pointed out that while we all might aspire to the density of Paris, most new buildings won’t look as beautiful as the ones in Paris, and this aesthetic deficit may harm the YIMBY movement. I responded that Japan looks nothing like Paris, but manages to build great-looking cities even though many of their buildings are rather cheap-looking humdrum concrete boxes. And I also argued that the new missing-middle construction in America’s inner-ring suburbs — townhomes, duplexes, and small apartment buildings scattered among single-family homes and a few local stores and cafes — actually looks really aesthetically nice, and is passing the market test in terms of people wanting to live there.

Patrick then asked me about how worried I was that Gen Z wouldn’t be able to handle the challenges of the new era. I responded that although phone-enabled social media is a big technological challenge to overcome, I think that Gen Z is evolving ways of avoiding mass social media and going back to the mix of small-group forums and offline interactions that made the internet such an awesome adjunct to the real world back in the 2000s. Between that and the effort to ban phones in schools, I’m optimistic.

Finally, Patrick asked me what my top three no-brainer, first-day policies would be if I were in charge of the country. My answers were:

Replace NEPA and other lawsuit-based environmental review laws with administrative review.

Enact national zoning; allow each location to choose its zoning from a simple menu of options created by the federal government.

Increase science funding by a large amount, as the CHIPS and Science Act originally tried to do (but more so).

Anyway, this was a great discussion, and I expect Patrick and I will do a follow-up. Maybe next time I’ll even ask him some questions!

2. Nobody is going to stop the energy transition

Republicans are generally hostile to solar and wind power because of culture wars over climate change. But beyond the self-contained bubble of American political signaling, the reality is that “green” energy is actually just cheap energy — especially solar. Technological revolutions do not care about your culture wars. And developing countries, who only care about getting rich and will use the cheapest source of electricity available, provide us with a good way to cut through the fog of American political B.S. and get an idea of which electricity sources are actually the cheapest.

Nat Bullard’s excellent annual presentation is a great source for some data here. Look how fast solar generation is increasing:

That’s actual generation, not capacity.

China is the biggest piece of this, of course, but other countries are hopping on the bandwagon. For example, Indonesia, which gets over 60% of its electricity from coal, recently announced a plan to phase it out and replace it mostly with renewables (with a bit of natural gas). And Turkey is installing solar at an accelerating rate. Meanwhile, about half of China’s exports of solar power equipment now go to developing countries rather than to developed ones.

Of course, in the U.S., the champion of solar installation is Texas:

Solar is the real standout here; wind is getting left behind, in the U.S. and in most of the world as well. The reasons are that A) wind takes a lot more land than solar does, so there are fewer places you can build it, B) wind resources are concentrated in only a few areas, whereas most places get a decent amount of sunlight, and C) wind’s cost declines haven’t been nearly as fast as solar’s. Wind is increasingly looking like it will end up being an important but niche energy source, like nuclear or gas. Solar, combined with battery storage, will be the backbone of the grid.

Nobody is going to stop this energy transition. Humanity has found a newer, better way of generating electricity, and countries that embrace it will reap the benefits accordingly. Too bad America’s Republican leadership is trying to keep us stuck in the past just to prosecute its culture wars.

3. Why do Americans die so young?

One chief way that Europeans cope with the fact that Americans are much much richer than them is to point out that Americans have lower life expectancy. Well, actually, that’s not even true; the U.S. and Europe have the same life expectancy. But if you look at the countries of West and North Europe — Germany, France, the UK, etc. — they do have about 2 to 4 more years, and that gap has opened up just since the 1990s:

Why does the U.S. lag on this metric? Usually, people in richer countries live longer; why not in this case? A common but false answer is that Europeans get better health care than Americans do, because of their universal health insurance systems. In fact, this accounts for only a small piece of the puzzle — Kaplan and Milstein (2019) looked at several high-quality studies and found that lack of health care explains between 0% and 17% of premature death.

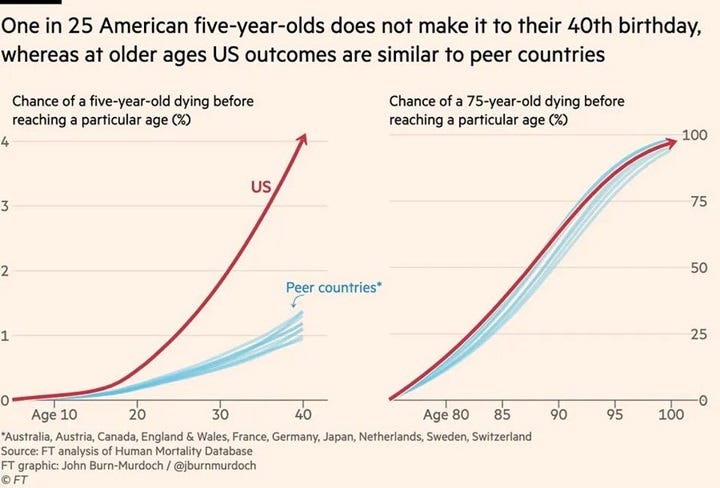

So what is causing it? It turns out that America’s higher death rates are concentrated among the young:

And what is killing young Americans? A whole lot of things, actually, but the biggest ones are drug overdoses, car accidents, drinking, and murder:

These are all behavioral or public health factors, not related to availability of health care. Americans are dying, broadly speaking, because we do a bunch of drugs, drive on dangerous roads, and kill each other. (Obesity is a factor too, which is a behavioral and public health issues as well.)

America’s high death rate isn’t a function of our health care system, but of A) our reckless and dangerous lifestyles, and B) our choices of other government policies such as speed limits, drug laws, and policing. We have used our vast wealth to consume ourselves to death. Universal health insurance might be a good idea, but don’t expect it to solve the low life expectancy problem; for that, we’ll need to change how we organize our society.

4. The “relationship recession” and falling fertility

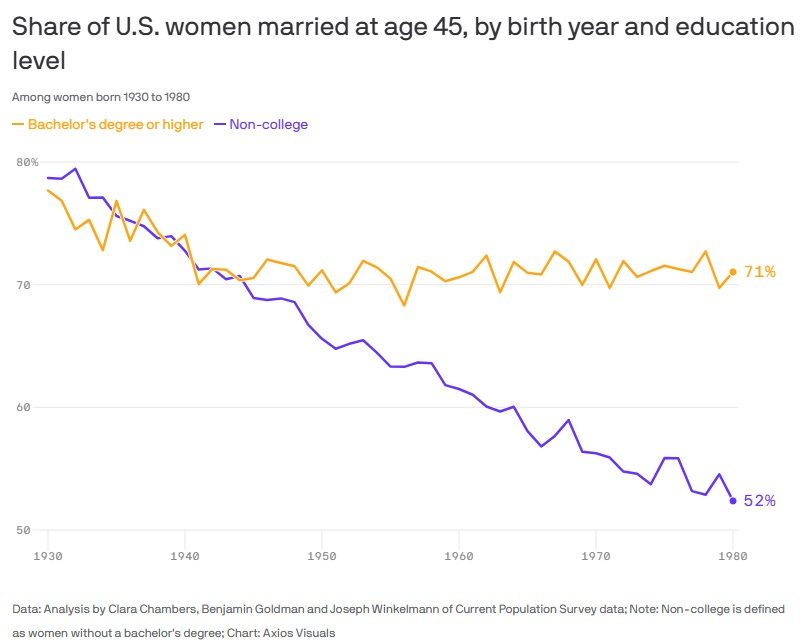

Everyone is worried about falling fertility rates, and yet nobody has a plan to raise them. But because of the greater attention being paid to the issue, we’re starting to examine some of the details of the problem, and we’re learning a few things. Once interesting fact is that in the past, falling fertility was more about married couples having fewer kids (often because they delayed having kids). As John Burn-Murdoch reports, the more recent drop is about people just not getting married at all:

Between 1960 and 1980, the average number of children born to a woman halved from almost four to two, even as the share of women in married couples edged only modestly lower. There were still plenty of couples in happy, stable relationships. They were just electing to have smaller families…But in recent years most of the fall is coming not from the decisions made by couples, but from a marked fall in the number of couples. Had US rates of marriage and cohabitation remained constant over the past decade, America’s total fertility rate would be higher today than it was then.

An obvious theory here is that more women are avoiding marriage because they’re working professionals who can make enough money for themselves. This theory is probably wrong, at least in America. In fact, educated American women are still getting married at rates similar to 1950, while less-educated women are getting married far less:

A new paper by Chambers, Goldman, and Winkelmann has a theory as to what’s going on here. They find that basically the entire decline in marriage is about non-college women no longer wanting to marry non-college men. Observing that earnings for non-college men have stagnated over the decades, the authors hypothesize that these men’s declining economic prospects are the reason why women don’t want to marry them.

Importantly, the authors argue that this isn’t just a composition effect, from more people going to college. In the mid 20th century, there was no difference in marriage rates between college and non-college men, so the opening up of that gap can’t be due solely to a change in who goes to college and who doesn’t.1

However, it’s still a leap to blame economic conditions for the change. It’s certainly possible that changes in behaviors like drug use and crime, or changing cultural values, are actually responsible for the decline in marriage rates between Americans who didn’t go to college. Also, the decline in fertility is global, while changes in working-class outcomes differ a lot from country to country, so I don’t think that declining economic prospects for working-class American men can explain most of the global fertility collapse.

But in any case, this result underscores an important point: America is doing a bad job at supporting working-class family formation. Fixing that could be key to fixing the fertility problem.

5. How to make sure the poor get a good education

One of progressives’ worst ideas is that standardized testing is inherently racist and classist. In fact, standardized testing is great for poor and disadvantaged kids’ educational opportunities, since it discovers and elevates talented kids who would otherwise be overlooked by the other parts of the system. This is a pretty well-known fact, but it’s reinforced by a new paper by Sacerdote, Staiger, and Tine:

We find that test score optional policies harm the likelihood of elite college admission for high achieving applicants from disadvantaged backgrounds. We show that at one elite college campus, SAT (and ACT) scores predict first year college GPA equally well across income and other demographic groups; high school GPA and class rank offer little additional predictive power. Under test score optional policies, less advantaged applicants who are high achieving submit test scores at too low a rate, significantly reducing their admissions chances; such applicants increase their admissions probability by a factor of 3.6x (from 2.9 percent to 10.2 percent) when they report their scores. High achieving first-generation applicants raise admissions chances by 2.4x by reporting scores. Much more than commonly understood, elite institutions interpret test scores in the context of background, and availability of test scores on an application can promote rather than hinder social mobility.

Basically, if submitting test scores on college applications is optional, poor and disadvantaged kids are often the ones who fail to submit them; this puts them at a huge disadvantage. So it’s important to make everyone submit their scores when applying.

Unfortunately, while a few colleges are moving back toward mandatory standardized testing, most are staying test-optional. One has to wonder if this is a cynical attempt to admit more rich students and fewer poor ones, in the face of declining enrollment and budget squeezes.

Another educational tool that gets unfairly maligned is AI. In the U.S., educators fret that AI will mainly be used to cheat on homework. But while that’s certainly happening, it’s also possible that AI tutors will turbocharge the quality of educational instruction. It has long been known that intensive personalized tutoring is the most effective educational intervention, but it’s expensive and hard to scale up. The hope is that AI will be able to give every kid a cheap high-quality personal tutor, like the primer in Neal Stephenson’s novel The Diamond Age.

In fact, this is now being tried in Nigeria, and the results are striking:

"AI helps us to learn, it can serve as a tutor, it can be anything you want it to be, depending on the prompt you write," says…one of the beneficiaries of a pilot that used generative artificial intelligence (AI) to support learning through an after-school program…A few months ago, we wrote a blog with some of the lessons from the implementation of this innovative program…

The results of the randomized evaluation, soon to be published, reveal overwhelmingly positive effects on learning outcomes. After the six-week intervention between June and July 2024, students took a pen-and-paper test…

Students who were randomly assigned to participate in the program significantly outperformed their peers who were not in all areas…These findings provide strong evidence that generative AI, when implemented thoughtfully with teacher support, can function effectively as a virtual tutor.

Students who participated also performed better on their end-of-year curricular exams. These exams, part of the regular school program, covered topics well beyond those addressed in the six-week intervention. This suggests that students who learned to engage effectively with AI may have leveraged these skills to explore and master other topics independently.

Moreover, the program benefited all students, not just the highest achievers. Girls, who were initially lagging boys in performance, seemed to gain even more from the intervention…

The more sessions students attended, the greater their gains…Importantly, the benefits did not taper off as the program progressed…The learning improvements were striking—about 0.3 standard deviations. To put this into perspective, this is equivalent to nearly two years of typical learning in just six weeks.

This fits with my general observation that we’re finding technological solutions to a lot of problems that people just assumed could only be solved by cultural and social change — obesity, carbon emissions, and so on.

6. Various thoughts on long-term growth

The long-term future of economic growth is a fun topic. There are a lot of big ideas, and few or no firm conclusions; this would normally be very frustrating, but when it comes to long-term growth, we’re not exactly under time pressure to produce results. Anyway, two big trends we’re observing in the world right now are population aging and the rise of AI, and it’s useful to think about how these might affect long-term growth.

In general, economists think that the effect of aging on growth is negative, because it means fewer researchers to discover new ideas. This is the central thesis of Jones (2022), probably the most important and well-known recent theory paper on the topic. But in a new paper, Jakob Madsen challenges this conventional wisdom. He argues that aging will temporarily benefit growth, by increasing savings rates — middle-aged people save more than young people. This, he argues, will finance more R&D, raising productivity growth rates.

I’m pretty skeptical of this argument. I don’t think savings rates are a primary constraint on R&D in the U.S. And looking at the evidence that R&D productivity is steadily slowing, it’s hard to think that an aging-driven increase in savings rates will be enough to turn things around.

While most people are pessimistic about aging, most are pretty optimistic about AI. While a few people think AI will supercharge innovation and productivity, more sober optimists tend to think the technology will raise growth rates by about 1 percentage point per year. In a recent paper, the OECD writes:

Briggs and Kodnani (2023) suggests an optimistic view based on their large aggregate productivity growth estimates, amounting to 1.5 percentage point (p.p.) labour productivity boost per year, comparable to the size of total productivity growth observed over the past decades…Aghion and Bunel (2024) use the framework in Acemoglu (2024) but rely on different assumptions…to arrive at numbers that are…closer to the optimistic end of the spectrum (around 1 p.p. point boost).

The OECD paper’s estimate is around 0.25 to 0.6 percentage points — a little bit on the lower end of the spectrum.2

A one percentage point boost is actually a whole lot — the difference between 3% growth and 2% growth means that living standards will double in 23 years instead of 35 years. But it’s not the Cambrian explosion that some AI boosters suggest.

Still, estimating the effect of a radically new technology from past data is incredibly tricky. In a recent post, Dwarkesh Patel envisions some uses of AI agents for corporate management, just to show how different AI could be from past technologies:

A few excerpts:

Currently, firms are extremely bottlenecked in hiring and training talent. But if your talent is an AI, you can copy it a stupid number of times. What if Google had a million AI software engineers? Not untrained amorphous "workers," but the AGI equivalents of [famous engineers], with all their skills, judgment, and tacit knowledge intact…

The power of copying extends beyond individuals to entire teams. Small previously successful teams (think PayPal Mafia, early SpaceX, the Traitorous Eight) can be replicated to tackle a thousand different projects simultaneously. It's not just about replicating star individuals, but entire configurations of complementary skills that are known to work well together…

Think about how limited a CEO's knowledge is today. How much does Sundar Pichai really know about what's happening across Google's vast empire?…Now imagine [an AI] mega-Sundar…[M]ega-Sundar might learn from everything seen by the distilled Sundars - every customer conversation, every engineering decision, every market response.

It’s not clear that past AI advances would be a good guide to the impact of this sort of thing.

So anyway, I don’t think there any firm answers here, but in general, I think it’s right to be worried about the long-term impact of aging on growth, and good to be excited about the long-term impact of AI.

However, when Chambers et al. separate out the earnings of non-college men who marry college-educated women, they are introducing a selection effect, which is why I don’t like that part of their analysis. But the main result stands.

Daron Acemoglu is an outlier, predicting almost no productivity gains from AI, but to reach that conclusion he had to arbitrarily assume away important parts of his own model!