Some thoughts on the future of the tech industry

The internet is mostly complete. Where does tech go from here?

I was sitting in a restaurant the other day, and a friend asked me “What’s going on in the tech industry these days?”. And because I’m terrible dinner company, I launched into a long rant about how we finished building the internet, so the tech industry is looking for something else to do, and blah blah. But apparently my friend thought the rant was interesting, and demanded that I publish it as a blog post. So here we are. Anyway, it’s a nice break from writing about the presidential election.

There are really two things in the U.S. that we mean when we say “the tech industry”. There are the big IT companies — Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Google, Amazon, Meta, and so on. And there’s the venture capital industry and its associated galaxy of startups. In fact, even put together, these two are only a piece of the real U.S. tech sector, which includes everything from little privately held software companies you’ve never heard of, to obscure hardware companies making specialized devices, to biotech, etc. A whole lot of American industry is high-tech. So when we say “the tech industry”, why do we mean “big IT companies and VC-funded startups”?

I don’t know for certain, but I’m guessing it’s all about financial returns. The “Big Tech” companies are absolutely gargantuan — they’re the most valuable companies in the entire world. And yet they didn’t cost a lot of money up front. Amazon is now worth $1.75 trillion, but the total amount it raised from private markets before its IPO was only $8 million, in a single Series A round in 1996. At the time, Amazon was valued at just $60 million. Even accounting for inflation, that’s a return of over a million percent!1

So there’s a lot of money to be made by picking the next Amazon, or the next Google, etc. This is why people lump together startups and Big Tech — the former, at least notionally, has a chance of becoming the latter. This is also how VCs make their money — top VC firms consistently perform much, much better than the median VC firm, and they do this by picking more big winners rather than by avoiding the losers. And even if you’re just some retail investor who bought Google or Facebook at IPO and held on to the stock, you’ve made quite a bit of money.

So when we say “the tech industry”, I think we mean the piece of the tech industry that offers the chance of a gigantic financial return. (Not unrelatedly, those companies also tend to pay their employees a lot. A mid-level manager at Google makes over half a million a year.)

The question of “the future of the tech industry”, then, is whether those kind of returns are still available — not just to a few very lucky people, but to the masses. And my intuition says it’s going to get harder going forward. Because fundamentally, I think the boom in tech returns was about the building out of the internet. And now that the internet has been pretty much built out, I think it’s not clear if any other effort — AI, deeptech, etc. — can offer the same kind of huge rewards for small commitments of capital.

The internet has mostly been built

“We did it Reddit!” — unknown

There was a time when railroad companies were hot growth stocks. There was a time when the companies building electrical grids and the telephone system were hot growth stocks, too. Some of these companies are still big today — Union Pacific, General Electric, AT&T — but they’re sleepy, slow-growing conglomerates in sleepy, slow-growing industries. The reason is that the railroads, the electrical grid, and the telephone network — now including the cellular network — have all been built. You don’t need to build them twice.

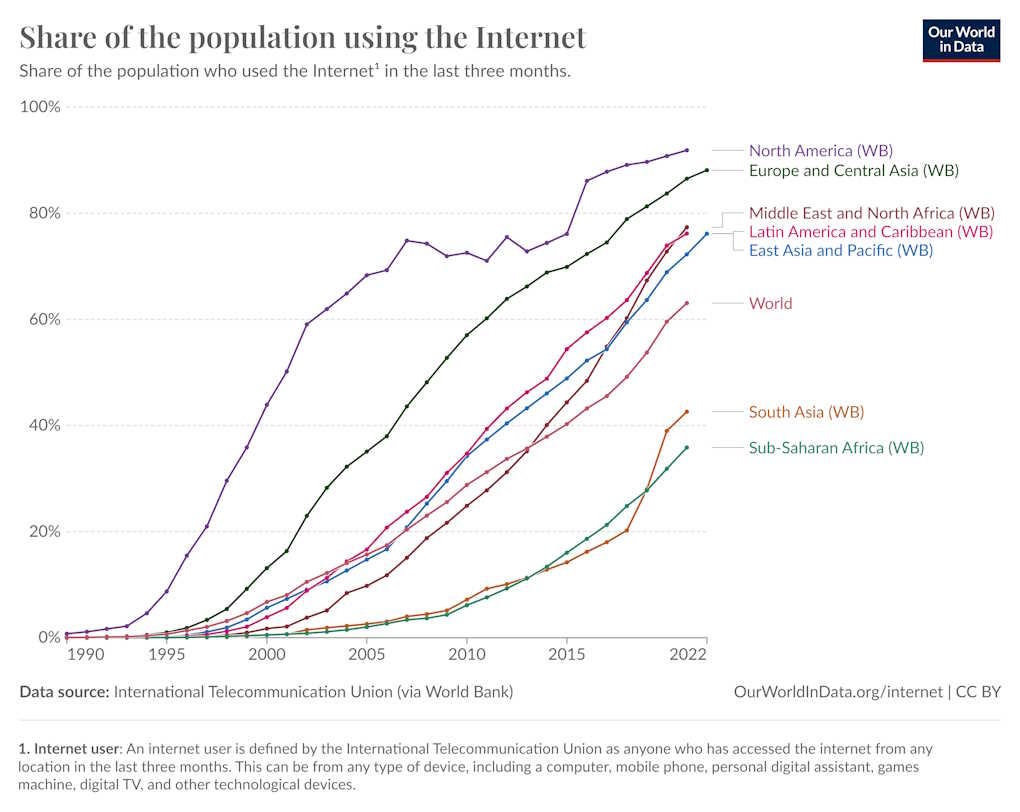

The global internet hasn’t quite been completed, but it’s getting there, particularly in rich countries:

There’s still some work to be done wiring up the countries that don’t have extensive broadband networks, but local telecoms and Starlink (or Huawei) will probably do most of that work. There’s not much growth left in the physical construction of the internet. The century-long quest to connect every human being on the planet with high-speed electric-powered text and voice communication is reaching its endpoint.

The final big piece of this physical infrastructure is cloud computing — the infrastructure that allows people to do all of their software tasks over the internet. That’s still growing, and it’s not clear whether it’ll level off soon — especially given the AI boom. Cloud computing has been key to the success of Amazon, Microsoft, and of course Nvidia. And depending on whether AI succeeds as much as people expect, it could see a boom in the coming years. So that’s a bright spot in the “internet is already built” narrative, though how much of a bright spot isn’t quite clear.

The part of the internet that has really been mostly built, though, is the consumer software layer.

Every technology, at a fundamental level, is about resource exploitation. Technology either opens up new resources to be exploited — for example, when steam power gave us a use for coal — or finds new, more valuable ways to use the resources we’re already exploiting.

Consumer internet technologies — Google search, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, etc. — is very cheap in terms of physical resources. In fact, that’s why people’s shift toward online socialization has been great for dematerialization of growth, and has taken a lot of pressure off of the planet. But there is one fundamental natural resource that these technologies use a lot of, and that’s time.

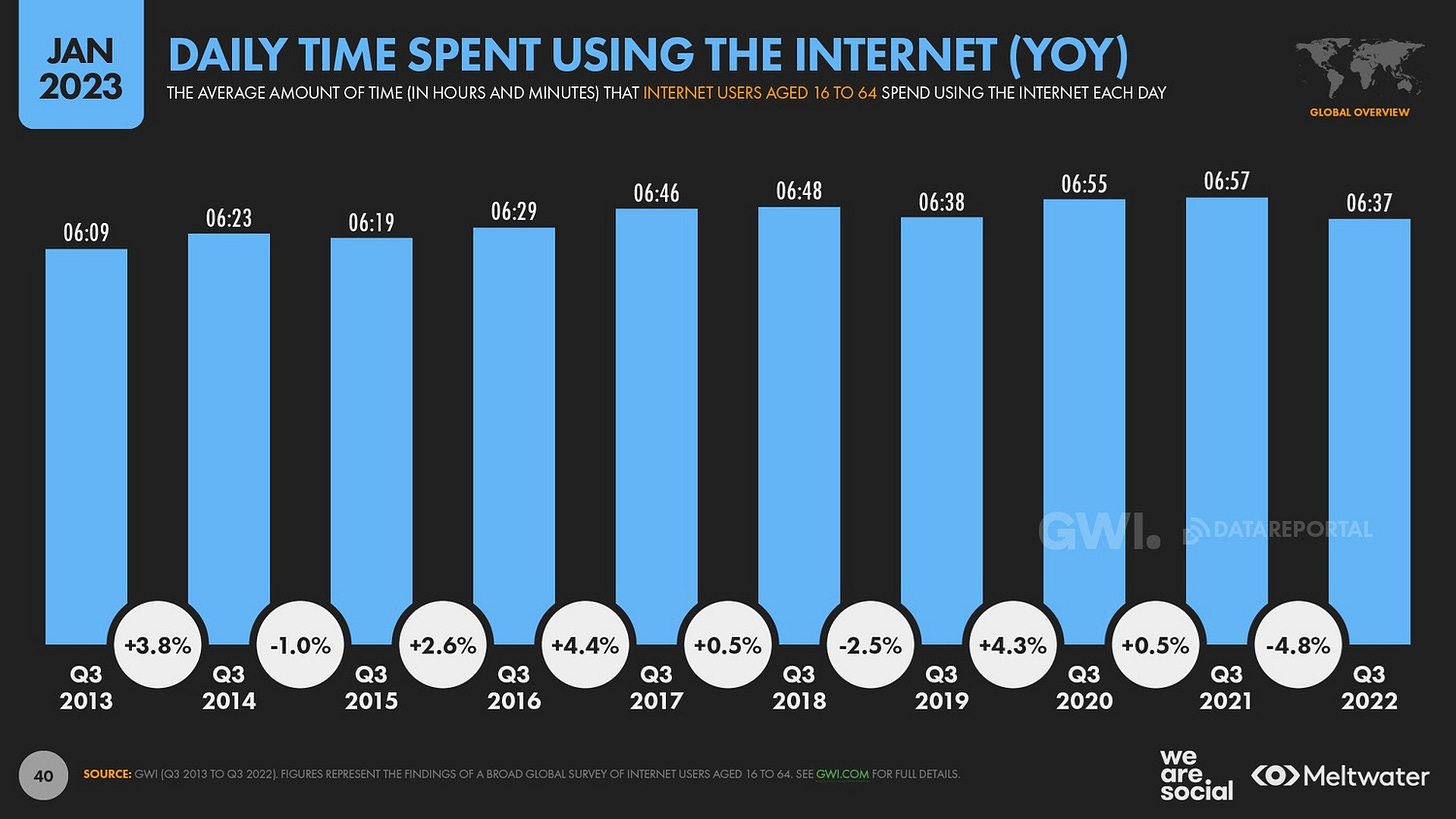

There are only so many hours in a day. Time you spend looking at your phone is time not spent working, doing housework, socializing with friends and family, watching TV, sleeping, playing with your pet rabbit, etc. For decades, the time that people in rich countries spent online rose and rose. But in the U.S., that number has plateaued at a little less than seven hours, and may now even be falling:

Where America goes, the rest of the world will follow. Time spent online is still rising globally as more people get internet access, but global average daily use of social media now appears to be falling.

The internet is fun, but there are only so many hours in a day — and that means only so many advertising dollars. The economic value produced by shifting from TV and books to the internet is real (though those other activities were already pretty fun, which is one reason consumer internet’s contribution to productivity growth has been modest). The economic value produced by shifting from offline socialization to online socialization is more dubious, since it can involve “product traps” where everyone is online even though most people would prefer not to be. But in any case, whatever that economic value is, it’s been pretty much mined out at this point. Even if we get better internet interfaces — VR, contact lenses, or whatever — we’re not going to have more time in the day to use them.

Of course, consumers aren’t the only ones who use the internet — businesses do too. That is what B2B software is mostly about, including the SaaS sector. But essentially all businesses in the U.S. now use the internet — every company has a website, every company uses various software productivity solutions. That doesn’t mean there isn’t more SaaS to be built — AI could help a lot here. But what it means is that new SaaS solutions are likely to displace old ones, rather than displacing obsolete, offline methods of doing business.

And that’s what a mature industry looks like. There are still plenty of successful new clothing companies — Lululemon, Shein, Uniqlo, etc. But because everyone already has clothes2, these companies’ success tends to come mostly at the expense of existing brands and manufacturers. Yes, clothes get a little better over time, and manufacturing processes get more efficient, but the pace of improvement is a lot more modest than in the past when awesome new materials were being invented left and right, and fashion for the masses was a growth industry.

Most internet industries will be the same. New social networks and video apps and SaaS solutions will arise, and some people will get rich from investing in them. But the pace will slow, because to succeed, those new software businesses will have to cannibalize the old ones. And remember that the value of companies today — big companies, but also startups — should take into account the chance that new competitors will come in and disrupt those companies in a few years.

In fact, I think that this is a large part of what the tech bust of 2022 was all about. Yes, the rise in interest rates triggered the big selloff, and yes there are concerns about the new antitrust movement going after Big Tech. But as I explained in a post back in 2022, I think some of it had to do with the fact that markets for IT stuff in general were smaller than people anticipated:

Take Shopify, for instance. Shopify was one of the medium-sized tech companies that took a big hit in the bust of 2022 and hasn’t recovered since:

Shopify isn’t a bad business — in fact, it’s a great one. The company is still worth $90 billion! But at the end of the day, it’s competing with Amazon for a limited pool of e-commerce dollars. The pandemic created the illusion that that pool was a lot bigger than it was, so maybe people thought that two Amazon-sized e-commerce companies could exist side by side.

In any case, the market crash felt like the correction of mistaken optimism that was pretty specific to tech. The NASDAQ has recovered, but it’s only up about 4.5% since the late 2021 peak, while the S&P 500 is up more than 13%. Tech companies had a giant wave of layoffs even as the economy as a whole went to record high employment rates.

Basically, I think the end of the pandemic and the rise in interest rates were triggers for investors to wake up and realize something they should have realized a while back: the internet is a mature industry now.

This isn’t a failure, of course, any more than the completion of our railroads or our electrical grid was a failure. In fact, it’s an incredible triumph, and the people who accomplished this feat will rightfully take their place in history. But in terms of expected returns, this presents a problem for both big tech companies and the VC/startup sector, because they’ve got to figure out where the next source of growth comes from.

Will AI, deeptech, or crypto pick up the slack?

There are a number of other places besides internet-related software and hardware that big tech companies and VCs can put their money. But the nature of the internet gave it some key advantages, from an investment perspective, that won’t necessarily be easily replicated elsewhere.

The internet is inherently a network business. It’s all about connecting people, whether physically or with software. The value of a network scales as the square of the number of nodes in the network, so this is a source of increasing returns to scale. Increasing returns to scale often create market power, because this means that big companies can naturally defeat small upstart competitors. And market power means profit. Software companies in general tend to have very high margins, and network effects (which also exist for other kinds of software, like Windows) are a major reason.

But because internet companies aren’t very capital-intensive, they don’t require huge fixed costs to set up — all you need to do these days is to hire a few software engineers and pay some cloud computing bills. Even back in the day when startups had to own their own computing hardware, it wasn’t that expensive. Together with network effects, low startup costs meant that software investors could take a huge number of bets, many of which offered the chance of gigantic returns.

The new industries that the tech sector is interested in mostly don’t offer both of these features at once. Crypto does, but so far crypto hasn’t really found many use cases, other than A) crime, B) capital flight, and C) convincing more people to buy crypto. It remains to be seen if crypto can find a real use case, but given that crypto’s only actual technological innovation is a distributed trust system, and distributed trust systems are inherently expensive, I am not super optimistic here. (Disclosure: I am still hodling…er, holding onto my Bitcoin and Ether.)

Deeptech is obviously incredibly useful — the world needs newfangled semiconductors, spiffy drones, better batteries, new cancer drugs, and so on. In many ways this is a return to form for the VC industry — before software took over, in the 1970s and early 1980s, VC was mostly about funding hardware companies. The high fixed costs of hardware are a source of increasing returns, and therefore a source of market power, which means hardware startups offer the possibility of big rewards.

The problem is that hardware, unlike software, has incredibly big startup costs. To scale up a manufacturing company, you have to build big factories, like Anduril is doing now with its “Arsenal” factory. Biotech companies have to pay the huge fixed costs of drug research, testing, and approval. This makes hardware a tougher investment in three ways.

First, it means fewer investors can participate in the market past the seed round — you just need to have a lot of cash to pay a meaningful percentage of those fixed costs. Second, it tends to put a cap on the rate of return — there are some extremely valuable hardware companies out there, like Tesla, but they generally require more investment capital than a Facebook or an Amazon. Third, and perhaps most importantly, it stops investors from diversifying, which increases risk. If you have enough money to invest in 100 software startups, but only 10 hardware startups, it means you have a better chance of catching the next Facebook than the next Tesla.

Deeptech is still great, and it’s what VCs used to do more of, but it’s going to be tougher going than internet software. One thing investors will try to do to mitigate these problems is to put their money in deeptech companies that only do design, not actual manufacturing — think of Apple and Nvidia here. But given U.S.-China decoupling and the inherent difficulty of retaining an edge in design without controlling the factories as well, there might not be so many design-only deeptech companies out there.

Finally, that brings us to AI. It was almost miraculous how generative AI — LLMs like ChatGPT, and AI art programs like Midjourney — arrived just in time to seemingly rescue the tech industry from the bust of 2022. Unsurprisingly, this has resulted in a flood of investment pouring into the sector. VCs are already allocating more than 20% of their dollars to AI in North America and Europe, but it’s Big Tech that’s really pouring in the cash. Goldman Sachs reports that FAANG companies are planning to spend $1 trillion on AI in the coming years.

A lot of people think AI is going to be absolutely transformative, and maybe it will. But it undeniably requires vast startup costs. Cutting-edge AI models now cost in the billions of dollars to train, and since AI improves by scaling exponentially, that could reach into the tens of billions soon. Some people in the industry expect trillion-dollar clusters in the future.

That’s a lot more expensive than a few geeks in a garage. And startups that hope to apply AI to business problems or consumer products are going to have to pay for their share of those enormous costs as well. AI, unlike internet software, is simply very capital-intensive.

As for the returns available to the winners in the AI sector, no one knows that yet. But people are starting to get skeptical that list of use cases will justify the amount of capital spending in the near future. Here’s Sequoia’s David Cahn:

In September 2023, I published AI’s $200B Question. The goal of the piece was to ask the question: “Where is all the revenue?”…At that time, I noticed a big gap between the revenue expectations implied by the AI infrastructure build-out, and actual revenue growth in the AI ecosystem, which is also a proxy for end-user value. I described this as a “$125B hole that needs to be filled for each year of CapEx at today’s levels.”…If you run this analysis again today, here are the results you get: AI’s $200B question is now AI’s $600B question.

And here’s Goldman Sachs:

GS Head of Global Equity Research Jim Covello [argues] that…truly life-changing inventions like the internet enabled low-cost solutions to disrupt high-cost solutions even in its infancy, unlike costly AI tech today…He’s also doubtful that AI will boost the valuation of companies that use the tech, as any efficiency gains would likely be competed away, and the path to actually boosting revenues is unclear[.]

Ominously, Character.AI, the most-used generative AI company, recently sort of sold itself to Google.

Most of these analysts do not agree with extreme pessimists like Ed Zitron; they don’t think AI is inherently just not very useful or capable. They believe that use cases will eventually be found to justify the cost of AI. But if it doesn’t happen soon, there could be a big bust in the AI industry, like there was in the railroad and telecom industries in their day.

That wouldn’t necessarily be the worst thing in the world, of course. The physical infrastructure that the boom is creating now — big training clusters full of GPUs — will be useful in the future even if many AI investments go bad (though perhaps marginally less useful than railroads or internet cables, since GPUs aren’t as durable as those other things).

And I fully expect businesses to eventually figure out how to build new business models that use AI more effectively than simply using it to directly replace humans at existing tasks. Just like electricity didn’t transform the economy until factory owners learned to reshape their factories around the new technology instead of simply trying to replace steam boilers with electric generators, I expect that the idea of “AI replacing humans” is just a clumsy, uninspired first pass at what this technology can do. AI might be overhyped in the short term, but I expect it to eventually reach Gartner’s “plateau of productivity”.3

But in any case, even if and when lucrative use cases emerge, it seems doubtful whether AI will ever have the kind of low startup costs that internet software companies have, just due to the inherent resource hunger of the technology.

And as for the possibility of big returns, it’s also not yet clear whether AI companies will have market power — or, in common business lingo, whether they’ll have a “moat”. Many technologies transform the world without ever being very profitable for the companies that produce them — witness solar power, for instance. Could AI be one of these?

Some engineers in the industry argue that companies building expensive foundational models — OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, etc. — have no moat. The reasons are that A) open-source models can be just as good as proprietary ones, and B) smaller models can be almost as good as the big expensive ones for a tiny fraction of the cost. If training costs aren’t as important, it means that fixed costs in AI will be less of a source of increasing returns.

As for network effects — the reason internet companies got so profitable and so huge — it’s not yet clear that AI companies have any of these. Yes, having more human customers allows you to get more human feedback, but it’s not clear that this actually makes AI products any better. Finally, some have suggested the rather cynical idea that big AI companies could use safety concerns to get the government to give them a moat, by regulating the industry such that only big companies can afford to pass the safety tests. But politicians plan to avoid this by making the regulations only apply to the big companies.

In other words, from an investment perspective, AI might end up having few of the key advantages of internet software (or hardware). No one wants to pay tens of tens of billions of dollars for a company that can’t make a lot of profit. And even if AI does become profitable, its cost structure will still make it more like deeptech than like internet software, from an investor’s point of view.

So I’m not sure there’s any technology on the horizon that can replace the bonanza that investors reaped from the internet. Tech might simply be slower, harder going from here on out.

What does it mean for tech to be a mature industry?

If tech is transforming into a mature industry, what are the implications? One is about growth vs. efficiency. Fast-growing industries can afford to be sloppy — to hire too many employees, and to ignore government policy unless it’s particularly egregious. Slower-growing industries don’t have that luxury — they have to please shareholders by wringing every last drop of efficiency out of their businesses, in order to please their shareholders.

This means that going forward, tech may be a somewhat less great place to get a job. In the 2010s, educated people of my generation believed that if whatever else they were doing happened to fail, they could always go get a high-paying job in tech. That may no longer be true; the recent round of layoffs might be the new normal.

It also means the tech industry might become more politically conservative. Highly educated people in America tend to be Democrats, and in the high-growth era, that was a luxury tech could afford. But in a world of slower growth, things like taxes and regulation become more important to a company’s ability to increase its profit margins. That creates a powerful economic incentive to support business-friendly policies.

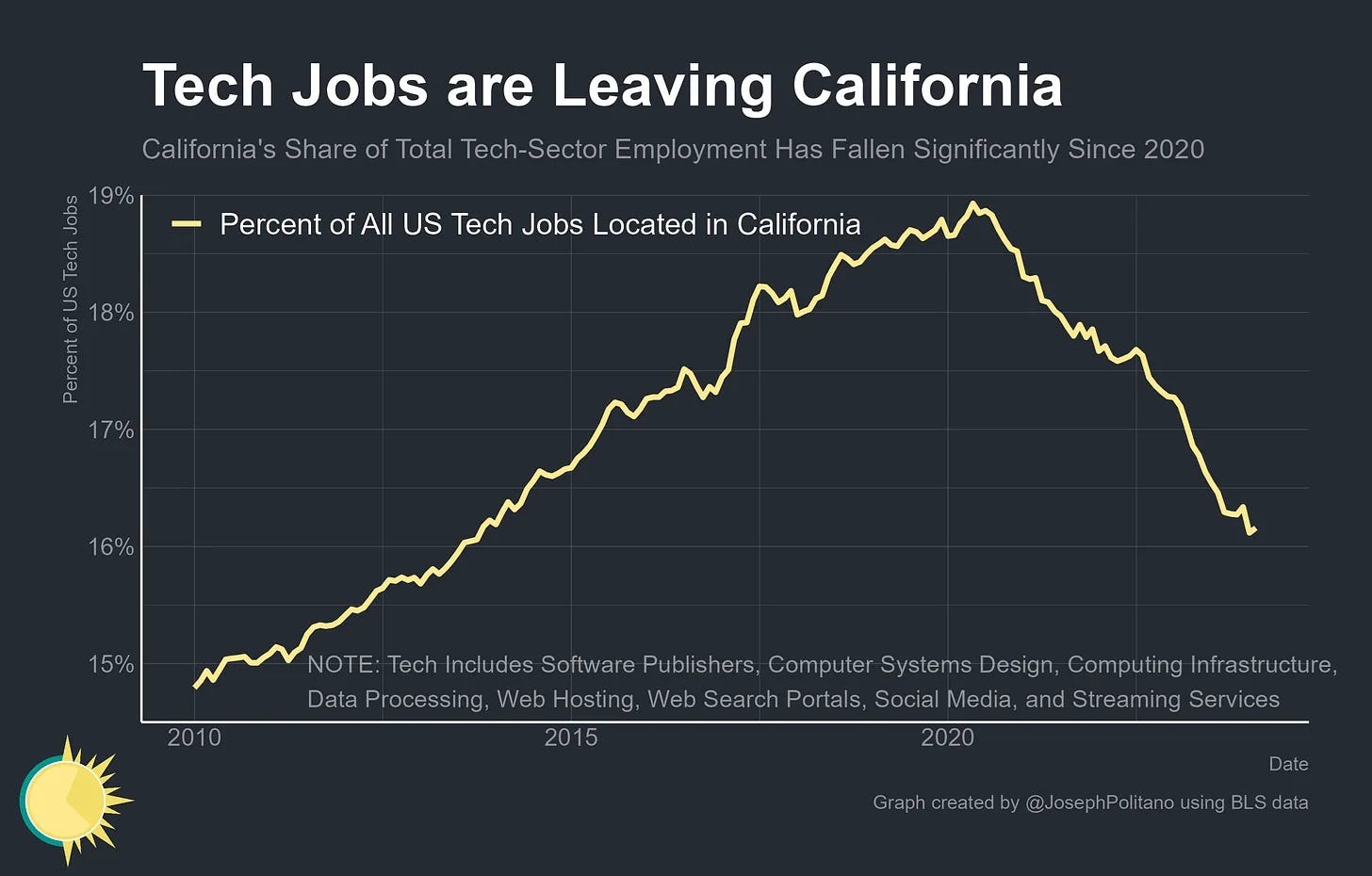

Finally, the maturation of the tech industry might produce one very welcome side effect — it might disperse high-paying jobs throughout the country instead of keeping them concentrated in tech hubs like Silicon Valley. For a fast-growing industry, access to investors is key — as a startup, for example, you need to be able to walk down Sand Hill Road and talk to all the VCs. But for more mature companies, saving on costs by moving some jobs to lower-cost areas might take precedence. Interestingly, there are signs that tech jobs are dispersing out of California:

Some of this is just California’s high housing costs, of course — but those were high back in 2016 as well. The rise of remote work also factors in here, but that’s just analogous to when manufacturers started to use railroads to disperse their factories throughout the U.S. back in the early 20th century. In general, geographic dispersion is the sign of a mature industry. So America’s declining regions — and some other countries — may now get more of a chance to share the wealth.

Anyway, all of this is pretty speculative and approximate. But many of the trends that we see in the tech industry today seem like they can be parsimoniously explained by the idea that the buildout of the internet was a very special, unique time in the history of technology and business. Progress continues, but as Vernor Vinge reminds us, rainbows end.

Yes, I know that Kleiner Perkins did not actually get $233 billion from its Amazon investment. This is just an illustrative figure. That said, holding on to early investments in tech companies is probably a good idea — if Bill Gates hadn’t sold his Microsoft stock, he’d be a trillionaire today.

Except for a few old guys in the Castro here in San Francisco, but let’s not talk about those guys.

Note that Gartner’s Hype Cycle isn’t very good at predicting the future of technologies — it’s just a retrospective tool for describing how they evolved in the past.

It took me 7 years from the start of the dot com revolution until when I got my first email address. I was an early adopter because it took 8 more years for the world to get email addresses due to the mobile revolution. So for AI, this is only year 2! It’s still early to make judgements. Everyone is waiting for that “killer” app or device that changes the world. Of course it’s better to be that early adopter positioning yourself to be in front of the crowd when it comes!

There are only so many hours - very good point.