Six reasons chipmakers should put their fabs in Japan

It has every resource the semiconductor industry needs.

Back in March, I wrote a post suggesting that semiconductor manufacturers like TSMC and Samsung should think about putting their fabs (chipmaking plants) in Canada. That was, admittedly, pretty speculative and long-term. At best, it would be something that would happen in 20 years or so, if the Canadian government started working hard right now to build capacity.

But there’s another place that chipmakers can put their fabs right now — a country with cheap land, labor, and capital, with a sophisticated existing semiconductor supply chain and lots of skilled workers. A country more secure from Chinese invasion than Taiwan, yet not as hobbled by domestic political divisions and labor-management struggles as the U.S.

That country is Japan.

In fact, this post is a bit late, since chipmakers are already investing quite a bit in Japan:

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. is considering building a third plant in Japan that would make advanced 3-nanometer chips…potentially turning the East Asian nation into a major global chipmaking hub…TSMC is in the process of building one fab in Japan for less advanced chips, and plans for a second facility have been reported earlier…

In addition to TSMC, Tokyo has successfully secured investments from Micron Technology Inc., Samsung Electronics Co. and Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. Japanese officials are also helping domestic startup Rapidus Corp. set up production lines for cutting-edge 2nm chips in Hokkaido…

TSMC is currently building a plant in the Kumamoto prefecture, with investments from Sony Group Corp. and Denso Corp., that is expected to start making chips as advanced as 12nm in late 2024. TSMC will also build a second fab, close to its first plant in Kumamoto, that is expected to start making 5nm chips in 2025, according to some of the people.

As the article notes, it’s not just Asian chipmakers doing this either — IBM is investing in Japan’s own foundry startup, Rapidus, which aims to compete with TSMC and Samsung. And Micron, the U.S. memory chipmaker, is investing $3.6 billion in a Japanese plant.

But these are potentially only the beginning of a wave of investment in Japanese semiconductor facilities. Japan has a ton of advantages over most other investment destinations. Here are a few.

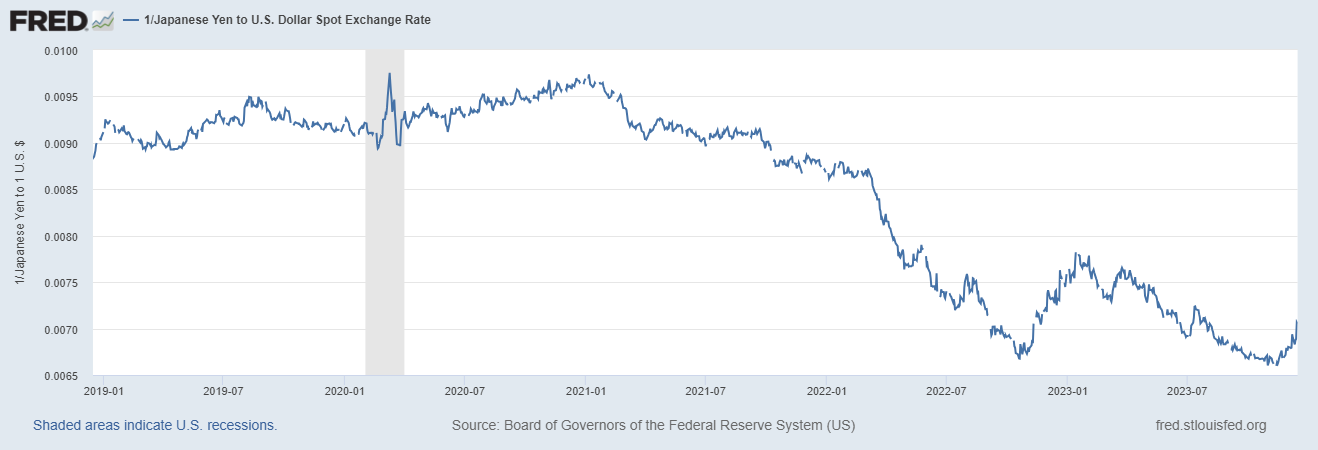

1. The weak yen (and low Japanese interest rates)

A yen used to be worth about 0.01 U.S. dollars — about one cent. Since the beginning of 2021, though, the yen has lost over a quarter of its value against the dollar:

There are various reasons for this, but the big one is low interest rates — because Japan has a less inflationary economy than the U.S. or Europe, Japan hasn’t raised interest rates as much as everyone else in the rich world. This means that Japanese bonds aren’t as attractive to investors, which has caused an outflow of money from the country. An outflow of money weakens a country’s currency. The Bank of Japan recently declared that it has no intention of ending the easy-money policy any time soon.

A year ago I wrote that the weak yen represents an opportunity for Japan, and I stand by this. It’s definitely a reason to build fabs there. A weak yen means that if your company’s earnings are in U.S. dollars or Taiwanese dollars or Korean won, it’s cheap to pay the construction costs for a fab in Japan. Wages for the workers at the fab will also look cheap. Inputs and equipment will cost the plants more, because they’ll have to pay yen to import those, but that’s almost certainly outweighed by the lower construction and labor costs.

In other words, the cheap yen is a mighty tailwind for just about anyone looking to use Japan as a production base.

As a side note, low interest rates also do one more helpful thing — they make it cheaper to borrow locally in Japan in order to finance fab construction. Japan’s 10-year government bond yield is about 0.66% — combine that with inflation of about 2.3%, and you get real long-term interest rates of about -1.64%. Compare that with U.S. real interest rates of about +1.67%. That’s a significant difference. (In theory, that should make capital flow from Japan to the U.S. until the interest rates converge and/or the yen appreciates against the dollar, but…in real life this equilibrating effect is often rather muted.)

2. An existing supply chain for tools and materials

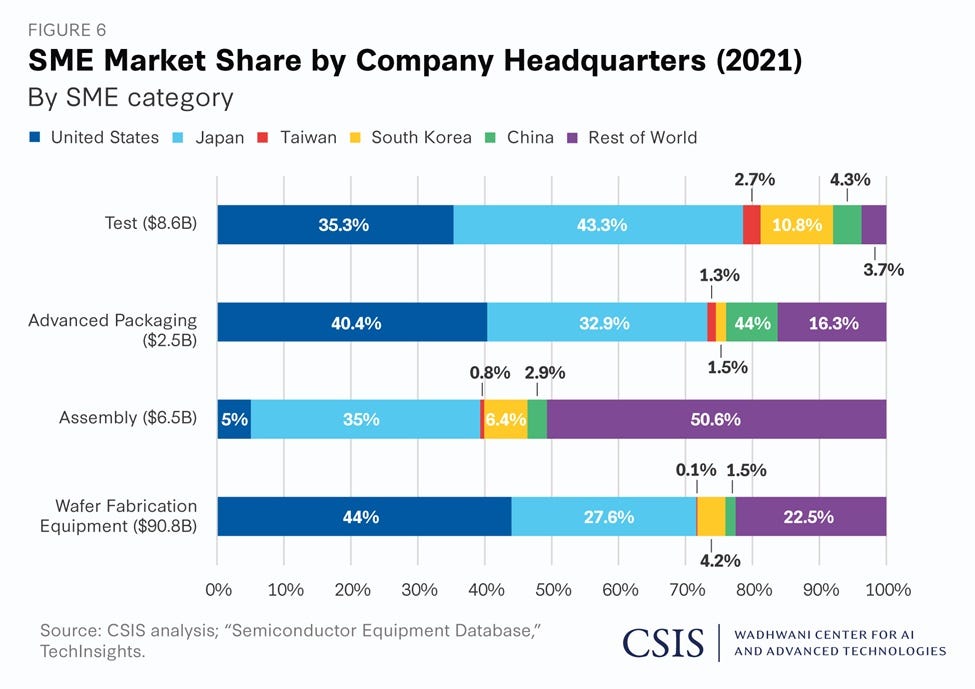

One great reason to put chip fabs in Japan is that a decent amount of the semiconductor industry supply chain is already located there. We tend to hear a lot about the countries that design and fabricate chips; Japan used to do a lot of this, but lost out in the 1990s and 2000s. But Japan still makes a lot of the tools and components that are used to make semiconductors.

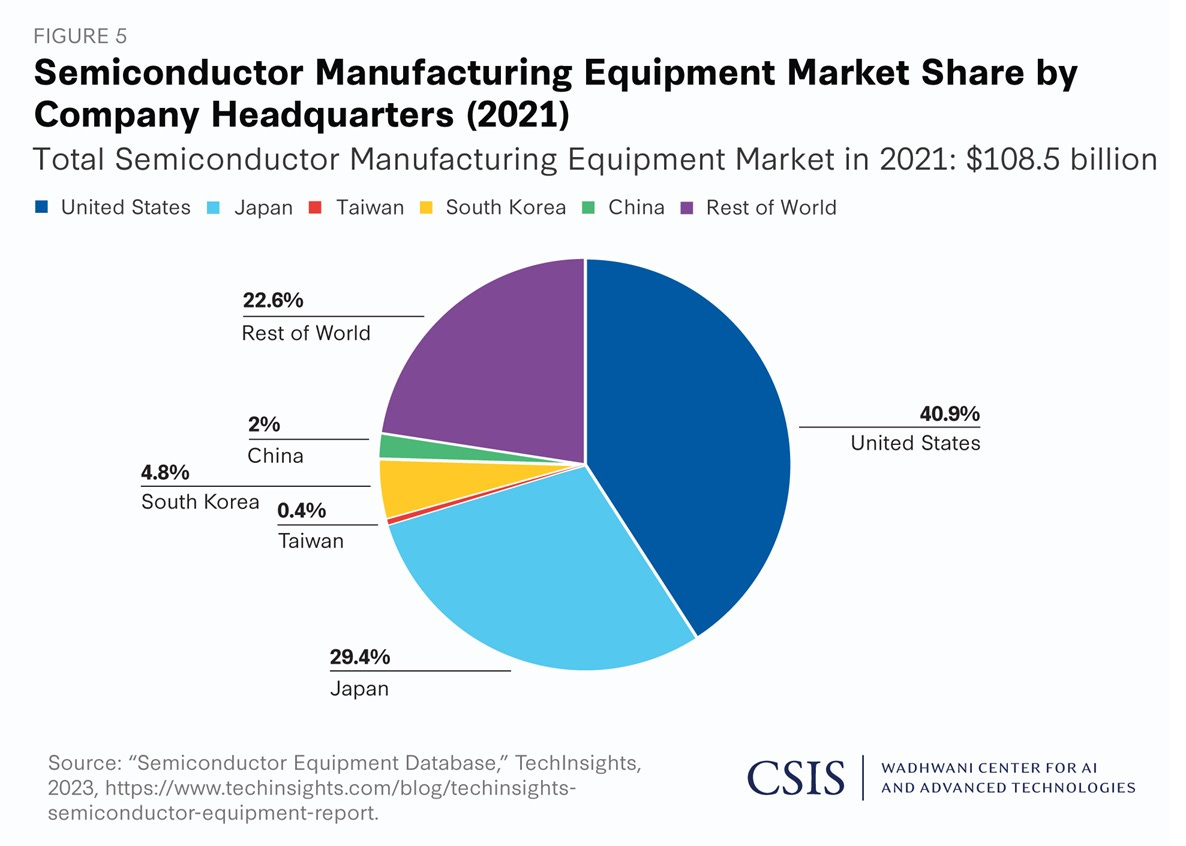

Here, let me borrow a chart from CSIS and put a red circle around the things Japan tends to do a lot of:

Japan is especially important for making the tools that are used to make chips — you hear a lot about the Netherlands’ ASML, but Japan is actually the second biggest toolmaker for the industry, behind only the U.S.:

An area where Japan is even more dominant is photoresist — a material used to make the molds used to carve computer chips. As of 2022, Japanese companies had a combined photoresist market share of more than 72%.

There are a few more examples like this. Chipmakers who put their fabs in Japan will have easy access to these pieces of the supply chain. But even more importantly, those Japanese semiconductor tool and component industries employ a whole lot of engineers who know a whole lot about making chips. Those engineers form a deep skilled workforce that companies like TSMC, Samsung, Micron, and the rest will be able to draw from.

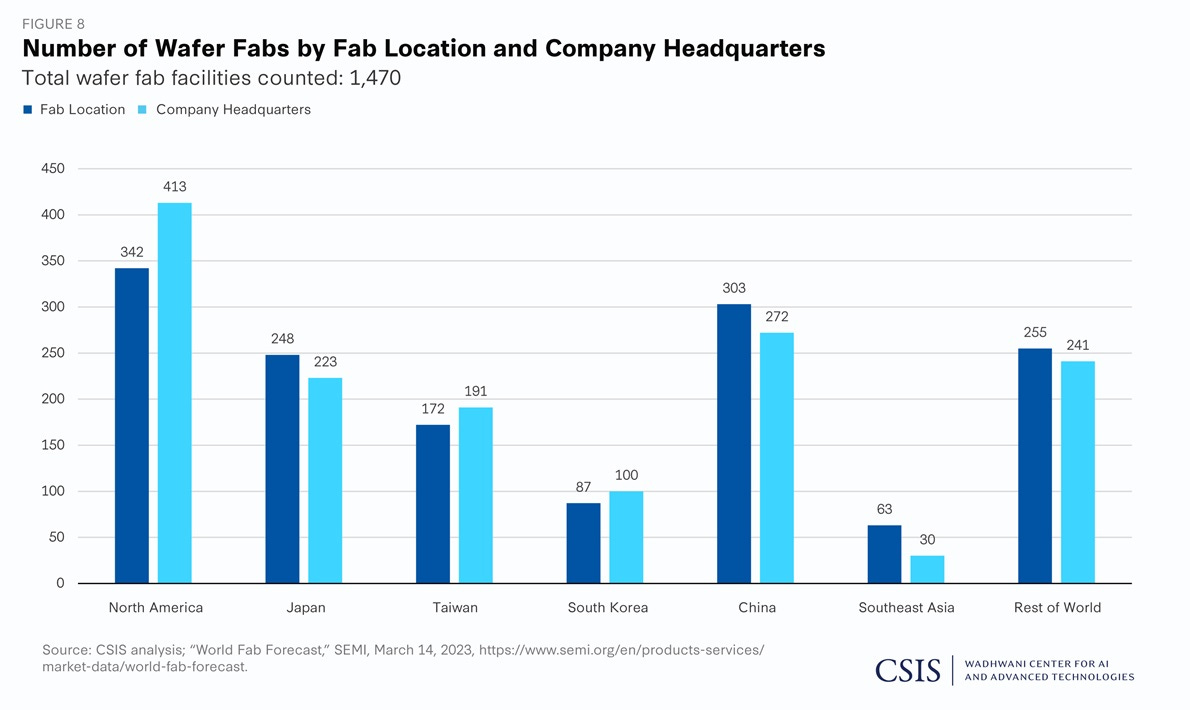

In fact, Japan also has a lot of existing fabs.

These tend not to be the leading-edge logic chip factories that we hear a lot about in the news, but they also have a deep pool of engineers who know something about how chipmaking works, and could quickly learn to meet the needs of TSMC, Samsung, or whoever.

Of course, hiring those workers will require a degree of worker poaching and mid-career hiring that corporate Japan often lacks. And because of the aging of the Japanese workforce, many of the workers will be in their 50s. So Japan’s labor market isn’t perfect, but it’s still pretty good. And the government will be keen to encourage both worker mobility and worker training in order to move things along.

3. A highly skilled yet affordable workforce

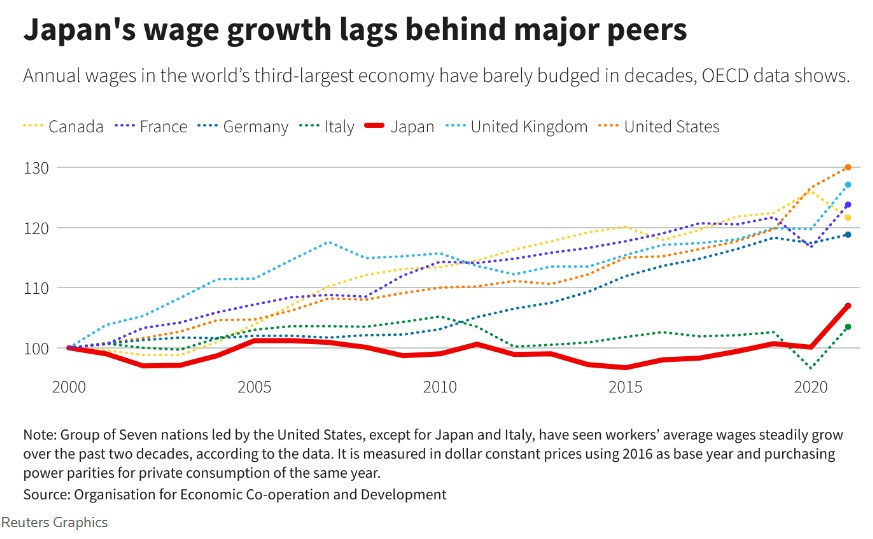

Japan’s economic stagnation over the past few decades has been crushing. Part of this is a general stagnation in wages, which has seen Japan fall behind most of the rest of the developed world:

This is obviously very bad for Japanese people. But from the perspective of a chipmaker thinking about where to put fabs, it’s actually a bonus. Low wages, coupled with a highly skilled and knowledgeable workforce, make for a very attractive labor force. In the U.S., if you want to hire engineers for a fab, you’ll have to compete with a software industry that pays workers $200,000 and up; in Japan, thanks to the combination of low wages and a weak yen, you’re looking at maybe a third of that at most.

One reason Japanese wages have performed poorly is the big shift from full-time workers — whose pay goes only up and up — to contract workers who have fewer guaranteed raises. That’s painful, of course, but the old lifetime employment system with seniority pay was actually very inefficient, so this is a needed change. And it will make the Japanese labor force more attractive to overseas investors. Japan also suffers from fewer bruising labor-management disputes of the type that recently held up TSMC’s construction of a fab in Arizona.

In other words, quite by accident, Japan has accomplished what economists call internal devaluation — increasing economic competitiveness by suppressing wages. German companies are often known to do this intentionally (with the support of unions!). But Japan has done it unintentionally, and competitiveness in the chipmaking industry is a small silver lining.

4. A lot fewer construction barriers

One thing Japan does a lot better than the U.S. is build. The U.S. is hampered by its court-centric system of environmental review, which allows local NIMBYs to sue to hold up development projects for years, even if those projects satisfy all environmental laws. In Japan, government ministries assign and adjudicate environmental impact assessments, with a limited and well-defined role for public comment rather than opportunistic lawsuits; this standardizes and speeds up the environmental review process quite a lot. Japan’s development regulations are also a lot simpler and more uniform, which allows Japan to build huge amounts of housing.

Japan’s strength in construction applies to factories as well as houses. Even as TSMC’s fab construction has struggled in the U.S., Nikkei Asia reports, it has powered ahead in Japan:

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. will begin installing equipment at its new chip plant in Japan this month, a sign that the project is proceeding more rapidly than the company's cutting-edge facility in the U.S…The $8 billion plant is on track to meet its target of beginning production by the end of next year and may even be ahead of schedule…

The relatively smooth progress at TSMC's first chipmaking facility in Japan stands in stark contrast to its plant in Arizona…

The Kumamoto project was announced in October 2021…and mass production is expected next year. Plans for the Arizona facility were unveiled in mid-2020…and yet mass production, which was originally slated to begin in 2024, has been pushed back to 2025…

U.S. regulations are more complicated…making it difficult for TSMC to bring its more than 100 suppliers to work with it in Arizona.

As the article mentions, the Arizona fab is larger and more complex than the ones in Japan, so the comparison is not entirely fair. But it stresses one more reason why construction is proceeding much faster in Japan: strong and decisive government support.

5. Government support

The Japanese government recognizes the tremendous opportunity offered by the global rearrangement and expansion of the chipmaking industry. The last 20 years have seen China cut Japan out of much of the global supply chain for electronics — an industry Japan once dominated. Losing its comparative advantage has probably contributed to Japan’s long productivity stagnation. Now Japan has a chance to reestablish itself as a core part of the East Asian electronics supercluster, and the government really doesn’t want to waste that opportunity.

This will require a lot of foreign direct investment. In the past, Japan avoided FDI, believing that Japanese brands should be the ones to control integrated supply chains. But while that approach worked in the relatively compact supplier networks of the 1970s and 1980s, it broke down when globalization dispersed supply chains all over the world in the 90s and afterwards. Now Japan’s government finally realizes that the country needs to be a collection of valuable nodes in a production system that stretches all across Asia, Europe, and North America. And that means attracting FDI.

As a result, Japan’s new industrial policy for semiconductors is oriented around a combination of support for domestic startups and incentives for FDI:

Japan is set to allocate almost ¥2 trillion ($13.3 billion) in an extra budget to boost its capacity to make and secure semiconductors at home…Of the total, about ¥760 billion will go into a fund to support the mass production of chips…About ¥640 billion will be used for another fund to support research of cutting-edge chips…About ¥570 billion will be assigned to a separate fund to enhance the stable supply of chips to Japan[.]

And:

The money will be used to speed up Japan’s ability to design and manufacture next-generation chips and train artificial intelligence models. Japan is setting aside funds for makers of high-end components, chip gear, industrial gases and semiconductor manufacturing, as well as for training engineers.

This sounds a lot like what the U.S. is doing, and there are many similarities. The U.S. famously dedicated tens of billions of dollars to semiconductor manufacturing with the CHIPS Act, passed in August of 2022. But while America is an absolute champion at assigning large numbers of dollars to projects on paper, it’s far less effective at actually getting those dollars where they’re supposed to go, much less translating the dollars into actual bricks and mortar. Japan, on the other hand, has a competent bureaucracy that dispatches subsidies with alacrity. The Nikkei Asia article I quoted earlier has a description of the difference between the two:

Japan has already earmarked 476 billion yen ($3.5 billion) worth of subsidies for the TSMC project. The U.S. only finalized the CHIPS Act, a package of support for the industry, last month and has yet to allocate its funds…The slower allocation of American subsidies could [increase] the time it takes chipmakers to install equipment in new plants.

This is one area where having a large, competent bureaucracy really makes a big difference. If you put your fabs in the U.S., you’re basically committing yourself to being at the center of a long series of battles between Republicans and Democrats, NIMBYs and pro-development forces, unions and management, and so on. In Japan, if you’re hitting a roadblock and you need something to go faster, at least you know who to call.

6. Hunger and innovation

Over the last two decades, Japanese companies lost their reputation for innovation, especially in the realm of electronics. National champions like Sony and Panasonic saw their corporate culture ossify and their brand leadership usurped by South Korean and Chinese rivals, while high-tech component makers saw their market share steadily eroded by Chinese competitors who were 80% as good and far cheaper. As a result, Japan’s reputation for producing blockbuster consumer products like the Sony Walkman, and for producing incrementally better high-tech gadgets every year, faded into memory.

But that old innovative spirit is still there, and Japanese businesses are hungry to regain their place in the world of electronics. Small Japanese companies are key players in the semiconductor industry, kind of like Germany’s “mittelstand” firms are in the world of mechanical engineering.

Those SMEs can partner with foreign chip companies.

But big Japanese companies are also occasionally able to produce surprising advances. For example, Canon is now developing a competitor to ASML’s famous EUV machines, which its chairman predicts will have similar capabilities at one-tenth the price. If that project succeeds, it will revolutionize global chipmaking, and fabs in Japan will be best-positioned to take advantage of it.

Then there’s the opportunity for joint ventures in the fab space. This is what IBM is trying to do with Japan’s Rapidus, which is supposed to be a competitor to TSMC. Other companies without their own foundry businesses (Intel?) might conceivably try something similar.

In any case, I don’t want to make it sound like I think Japan is headed for dominance in the semiconductor industry. Instead, I think it will reintegrate itself into a supply chain that includes the U.S., Taiwan, South Korea, and Europe — a globally distributed web of high-tech companies that cooperates more than it competes, and which is dedicated to the overriding purpose of staying ahead of a hard-charging China. That’s a very feasible goal for Japan, rather than the single-country dominance it aimed for in the 1980s. And that’s why I predict that chipmakers are going to continue investing there.

Regarding building wafer fabs in Japan vs. the US, I have no reason to doubt your assertions about the regulatory climate in Japan being more favorable. You've convinced me that you know more about Japan than I. However, I must reserve judgement whether their bureaucracy is better than ours.

No matter. My comment has to do with your thesis that Japan is a solution for Taiwan's existential crisis. I'm reminded of the three little pigs. The straw house (Taiwan) offers no protection, but the wooden house (Japan) does. Your opinion is that building a brick house (US) is neither feasible nor cost effective.

The real issue is whether moving a strategic trans-Pacific supply line from Taiwan to Japan makes any difference, when the real peril is that the Pacific shows signs of becoming a Chinese lake. A slight overstatement, but one that China would endorse. As another reader has pointed out, Japan is worringly analogous to Finland.

After having spent my career in the semiconductor industry in the US and being familiar with the industries in Europe, Taiwan, Korea and Japan, I don't see a compelling argument that the US is uncompetitive in engineering skills, manufacturing equipment, semiconductor technology or supply infrastructure. Ditto for the large labor pool of fab operators and maintenance technicians. Japan, by comparison, is faced with shrinkage of the key labor demographics that drive this industry. Finally, the US is the World's engineering and physics classroom.

Another subtle downside is interference from unproductive labor unions (supported by government) in both the US and Canada. A new fab plant in Arizona is getting some union blowback about hiring.

Yes, there's bad management and bad unions. But the incentives in US labor law make the latter 10x worse.

In the '80s, I grew up with extended family members in the US domestic auto sector, both management and labor. The myopia and entitlement mindset within both was stunning to a teenager told to always "work hard". As was the subtle racism directed at Japanese car brands.

It's better today, but there's still a large productivity gap between union and non union plants.