Why not put TSMC and Samsung fabs in Canada?

A solution that's almost too perfect.

The semiconductor fabrication industry must diversify geographically. Currently, the fabrication of leading-edge semiconductors is highly concentrated in Taiwan, because it’s dominated by a single company, TSMC. (There’s also a little bit of production in South Korea, thanks to Samsung, but mostly it’s just TSMC.) This concentration represents an unacceptable risk to the global economy, for two big reasons.

First, in the event of a war with China — a scenario that’s looking ever less unthinkable — Taiwan will certainly be either blockaded, bombed, and/or invaded. This would interdict or destroy most of the world’s production of leading-edge semiconductors, leading to a chip shortage that would make the post-pandemic crunch pale in comparison. Many industries would grind to a halt. (South Korea and Japan are also vulnerable to Chinese blockade and attack in the event of an East Asian war, though less so than Taiwan.)

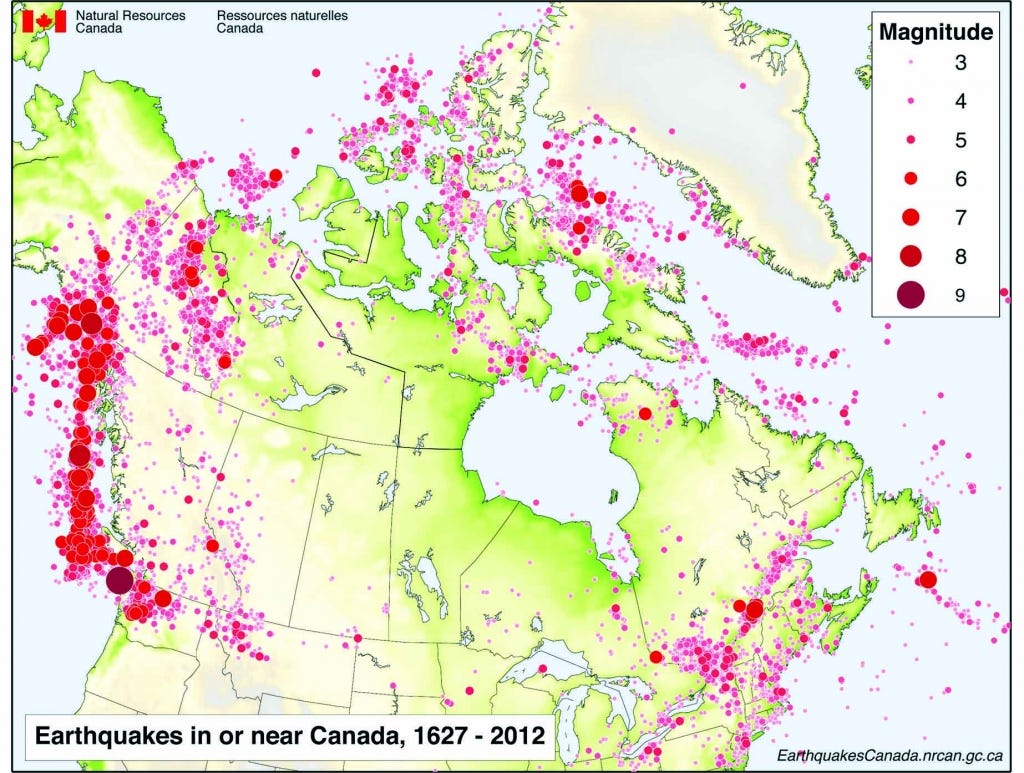

But in fact, what’s even more likely than a Chinese invasion is a big earthquake. Taiwan is in one of the most seismically active regions of the globe, and it’s only a matter of time until the next big one hits. Semiconductor fabrication, meanwhile, is getting so precise that its tolerance for seismic interference is going down. A big earthquake could be just as damaging to global chip supply as Chinese bombs, and earthquakes are not amenable to diplomacy or deterrence.

In other words, in order to guard against massive chip disruptions, TSMC needs to move some of its fabs to other countries far away from China and earthquakes. Currently, the main pressure to do this is coming from the United States, so that’s where TSMC is diversifying to. A big fab is being built in Arizona. Samsung, meanwhile, is building fabs in Texas.

Why America is hard

But these expansions are already running into big hurdles, because America is the Build-Nothing Country. Already, costs are ballooning for the new chip fabs just like they tend to do for every other big American project:

“A range of construction costs and project uncertainty in Phoenix makes building the same advanced logic wafer fab in Taiwan considerably less capital intensive,” TSMC said in a letter last month to the Commerce Department. “The real barrier” to setting up manufacturing in the U.S. “is comparative cost to build and operate,” it said…

TSMC Founder Morris Chang said chip manufacturing costs in the U.S. are about 50 percent higher than in Taiwan, and TSMC also told the Commerce Department that federal regulations and addition site preparation have raised the cost of the Arizona plant…On its hiring challenges, the Arizona facility now has about 1,000 employees with that number expected to double in 2023. To induce Taiwan-based TSMC engineers to move to Arizona, the company has offered doubled salaries and higher benefits[.]

The first problem is that due to America’s arduous permitting process — which even the advocates of industrial policy tend to defend and make excuses for — allows local interests to delay projects for years by forcing them to submit lengthy environmental reviews through the court system, massively increasing the time, cost, and uncertainty involved.

Second, the U.S. government is not used to doing industrial policy for its own sake; instead, it’s accustomed to taking growth for granted and using government policy to spread the benefits of growth around. Therefore CHIPS Act, which is providing the main financial boost for TSMC’s American fab expansions, has attached a ton of requirements and riders to this support — child care provision, “Buy American” requirements, mandatory partnerships with various nonprofits, and so on. This all adds cost upon cost.

Third, the U.S. doesn’t have a lot of the requisite workers. Because the chip fabrication industry mostly migrated out of the U.S. a while ago, there aren’t a lot of Americans who know how to work the incredibly complex machinery at a TSMC plant. And those who have the talent and background education to do the job will tend to demand extremely high wages — their alternative is the software industry, which pays $300-$500k a year for a mid-level coding job.

TSMC’s executives have claimed that American work ethic isn’t up to Taiwanese standards, claiming that Taiwanese workers will work nights and weekends while Americans refuse to do so. This is complete bunk; Americans work nights and weekends more than almost anyone in the world, and our top earners work even more than our bottom earners. The problem is that in order to get Americans to work that hard, you have to pay them a lot more than you have to pay Taiwanese people. The average salary for a TSMC worker in Taiwan is about $100,000; that’s about half of what an American tech worker can make in their first year as a coder at Google. Of course it isn’t TSMC’s fault that U.S. workers demand so much money; it’s just the incredible gravitational pull of America’s software industry mega-cluster.

Of course, the U.S. could simply import the requisite talent from Taiwan, Korea, and maybe Malaysia via the H-1b program, visa waivers, or other visa programs. Perhaps the “tethering” effect of visas or visa waivers would even allow TSMC to pay Taiwan-like wages in the U.S., by preventing fab workers from defecting to high-paying software jobs. But the U.S. has seen a remarkable politicization of immigration since the Trump era, and bringing in a ton of foreign workers is sort of a third rail of politics at the moment.

Even many progressives who are nominally pro-immigration are likely to oppose a mass importation of chip fab workers, since they think of industrial policies like the CHIPS Act as a jobs program rather than a matter of national security. Progressives tend to dismiss the notion that domestic skills shortages can even exist, preferring to call for higher wages (which of course adds massive costs) and the training of native-born workers as an alternative (even though this takes many years).

In other words, although massive federal subsidies and a slowly building sense of urgency will probably get some fabs built in the U.S., it’s a massive uphill battle. And yet the urgency of diversifying leading-edge chips out of Taiwan and Korea remains, and the threats from war and earthquakes will not wait for U.S. political economy to rouse itself from decades of torpor and zero-sum infighting.

Solution: Canada

There’s a fairly obvious solution to this problem hiding in plain sight, and it’s called “Canada”. Nearly every reason why it’s hard to build leading-edge fabs in America is not present in America’s neighbor to the north.

Canada is obviously just as safe from Chinese missiles and ships as Arizona is. But its central region — Ontario, Manitoba, and Eastern Alberta — even more safe from earthquakes. The Canadian shield rock makes this one of the planet’s least seismically active regions:

There are occasional tornadoes, but Ontario is very low-risk for this as well. Ditto for wildfire risk.

Semiconductor fabs also use a ton of water. That’s a big problem in Arizona, but no problem at all in Ontario or Alberta.

Land acquisition and development are going to be a lot cheaper in Canada as well. Average land costs in Ontario are about $4000-$5000 per acre, compared to over $7500 in Arizona. Permitting also is going to be much more easier in Canada, which has streamlined its permitting process and doesn’t have nearly as many court challenges as in the U.S. Basically, Canada uses more of a “high-end” strategy of regulation, where bureaucrats decide if projects would be environmentally harmful, compared to America’s “low-end” strategy where local parochial interests are responsible for enforcing environmental law by suing each other opportunistically.

Finally, there’s labor. Canada is not a software industry cluster. This means that its software salaries are far, far lower than in the U.S. — for example, the median total compensation for a software engineer in the Greater Toronto area is only about $100k, competitive with TSMC salaries in Taiwan. In Canada, therefore, TSMC wouldn’t need to worry as much about employees jumping ship.

Canada would also be no problem for bringing in skilled workers from Taiwan, Korea, or any other country. It has the most generous large-scale high-skilled immigration program in the world.

Where the U.S. will challenge any proposed influx of foreign fab workers with demands to prove that the foreigners won’t displace the native-born or lower wages, Canada will simply say “Yes, how many would you like to bring over?”.

Central Canada is also home to some safe and diverse major population centers — Toronto and Calgary — that could provide a source of local workers and a place for fab workers to live and enjoy themselves. These cities, along with Montreal, already have a little bit of semiconductor activity that could provide a base to build on. The fabs themselves would of course have to be located outside the cities to avoid high urban land costs.

The one major source of high costs for Canadian semiconductor fabs will be the difficulty of sourcing parts, materials, and equipment — a problem that also exists in the U.S., thanks to decades of divestment from chip fabrication. But this constraint is not particularly more severe than it is in Arizona, especially because the U.S. itself is right nextdoor.

Of course, some of the American politicians who are providing the political impetus for TSMC to move production to the U.S. may not be so enamored of the Canada solution; they’re hoping that TSMC’s investments will create jobs for Americans, after all, not for Canadians. But the central imperative of national security and supply chain security would be fully satisfied by TSMC fabs in Canada. And if American politicians really want to boost local industry, they should consider reforming their onerous permitting processes, opening up their country to skilled immigration, and not using industrial policy as a vehicle for giveaways to local nonprofits, care industries, and domestic metal producers.

So if I were TSMC or Samsung, I would be taking a look at Canada as a place to diversify into. And if I were the government of Canada, I would think about bolstering these natural advantages with a vigorous industrial policy to cultivate foreign investment — and, eventually, domestic investment — in the chip fab industry. So far, Canada has mostly ignored this possibility, but if there was any moment to try to move into semiconductor manufacturing, that moment is now.

Fabs don’t require software engineers. They require materials and mechanical/electrical engineers, but mostly skilled technicians. Totally different education and skill set.

Also... 300-500K isn’t a mid-level programmers salary (you have been in San Francisco to long).

But aside from that, it’s a good idea.

It's funny, because I had a similiar pitch back when everything was going down with Hong Kong to try and convince as many people and financial institutions to flee to Vancouver/Calgary.

Honestly the Federal government in Canada has never seemed willing to really actively take advantage of high immigration rates, to deliberately either steal firms or strip authoritarian countries of talent. Instead they end up passively being the consumer of last resort for PhD students and engineering grads from US universities who can't get green cards. Which is good, but feels like a missed opportunity.