Roundup #75: Checking in on the Bad Guys

Iran; China vs. India; Russia; Leaving California; Reduced hiring; Indian development; Wind energy; Science funding

It’s a new year, so I’ve decided to change how I name these roundup posts. I’m retiring the name “At least five interesting things”, which is cumbersome and felt a little repetitive. Instead I’ll just call it “roundup”. I’m keeping the numbers for now, so people who want to link back to a specific roundup post can differentiate them.

Anyway, I’ve got a couple of fun podcasts for you, both about AI! The first is me and Liron Shapira on his podcast Doom Debates, talking about AI safety, and referencing my post on that topic from a few weeks ago:

The second podcast is with Jeff Schechtman, in which I make my case for techno-optimism and complain that Americans are too fearful of the future:

Anyway, on to this week’s roundup! Consistent with the theme of “Checking in on the bad guys”, let’s start with some items about the New Axis powers:

1. Iran’s chaos is partially economic

Everyone’s eyes are fixed on Iran’s protests and the regime’s brutal response to them, waiting to see if the Islamic Republic falls or manages to shoot its way out of this crisis. But it’s also interesting to take a look at the material roots of the unrest. Zineb Riboua has an article in The National Interest detailing some of the regime’s failures on the economic front. One key issue that relatively few outsiders seem to know about is the country’s water crisis:

Crucially, the regime’s failures are starkly visible in Iran’s accelerating water crisis, which has evolved from an environmental strain into a political fault line. A country of more than 90 million people is confronting its worst drought in over half a century, with collapsing aquifers, dried rivers, and water rationing spreading across cities and provinces. Instead of addressing decades of reckless dam construction and unsustainable agricultural policy, the regime has increasingly shifted blame outward. Iranian officials and state-aligned media have accused neighboring countries such as Turkey, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia of diverting rain clouds, and more recently have alleged that the United States and Israel are manipulating the weather.

Moreover, Iran’s water crisis directly contributes to prolonged power cuts that further intensify unrest. Power generation in Iran depends heavily on water-intensive infrastructure, leaving the grid vulnerable as reservoirs shrink. Chronic blackouts now disrupt daily life, turning infrastructure failure into immediate political anger and, alongside water shortages, accelerating mass unrest.

U.S. sanctions have also made a big impact. Iran has been forced into all kinds of alternative financing arrangements, and now sells most of its oil to China. This makes it a lot harder for Iran to pay for its military:

These constraints combined have produced a profoundly distorted budgetary structure. Iran’s national budget is effectively bifurcated between rial-denominated and crude-oil-denominated allocations. Because Iran cannot sell its oil through conventional financial channels, it increasingly uses oil as a substitute for cash, primarily to fund the security sector. The Ministry of Defense, for example, receives both rials and oil shipments, which it must then sell independently to finance weapons, operations, and support for proxy forces.

Sanctions have also forced Iran into a fairly classic currency crisis, with inflation spiraling out of control and causing all of the usual disruptions:

[I]nflation has reached crisis levels, with official data showing a rate of 42.2 percent in December 2025, up 1.8 percent from November, while food prices surged 72 percent and health and medical goods rose 50 percent year on year. Combined with a mismanaged water crisis, these pressures sharply raise the cost of basic necessities…[T]he erosion of pensions and savings forces households to abandon long-term planning and shift into survival mode…

Jared Malsin also has a good article in the WSJ about how the current economic unrest was triggered by a recent financial crisis:

Late last year, Ayandeh Bank, run by regime cronies and saddled with nearly $5 billion in losses on a pile of bad loans, went bust. The government folded the carcass into a state bank and printed a massive amount of money to try to paper over all the red ink…[T]he failure became both a symbol and an accelerant of an economic unraveling that ultimately triggered the protests…The country’s beleaguered currency, the rial, tipped into a new downward spiral the country had little ability to stop.

Both articles have plenty more interesting details.

In addition to a fascinating look into the anatomy of an emerging-market resource-exporter’s economic collapse, I think there are two big takeaways here. The first is that protracted sanctions on a country — especially a resource exporter — can succeed, but only after many years and a whole lot of pain and suffering. This has lessons for our sanctions on Russia — don’t expect quick results, and expect ordinary Russians to feel a lot of pain before it’s all over.

The second lesson is that broad-based unrest tends to require economic hardship. Students and urban middle classes may march in the streets for freedom and individual rights and democracy and such, but truly regime-threatening unrest, of the type we’re now seeing erupt all over Iran, typically requires the business class and the working class to both suffer hardship.

2. China is still trying to stop India from industrializing

Last March I wrote about China’s attempts to kneecap Indian manufacturing. I linked to this Kyle Chan post:

India represents the most striking case of Beijing’s effort to shape the international behavior of Chinese firms…[A]cross a number of industries, Beijing seems to be discouraging Chinese firms making future plans to invest in India while also limiting the flow of workers and equipment…Beijing appears to be limiting Apple’s manufacturing partner Foxconn from bringing Chinese equipment and Chinese workers to India. Some of Foxconn’s Chinese workers in India were even told to return to China. This informal Chinese ban extends to other electronics firms working in India…Beijing has told Chinese automakers specifically not to invest in India…China has been reportedly blocking the export of Chinese solar equipment to India…[Tunnel boring machines] made in China by Germany’s Herrenknecht for export to India have been reportedly held up by Chinese customs.

In recent months, China has increasingly been using export controls — mostly on rare earth and battery technologies — to achieve its geopolitical and economic goals. Now it’s using these controls to try to prevent India from developing a battery industry:

Reliance Industries Ltd. has paused plans to make lithium-ion battery cells in India after failing to secure Chinese technology…The Mukesh Ambani-led oil-to-telecoms conglomerate, which had aimed to begin cell manufacturing this year, had been in discussions with a Chinese lithium iron phosphate supplier Xiamen Hithium Energy Storage Technology Co. to license cell technology…Those talks stalled after the Chinese company withdrew from the proposed partnership amid Beijing’s curbs on overseas technology transfers in key sectors…China has stepped up scrutiny of clean-energy technology deals as it seeks to protect strategic advantages in sectors.

This demonstrates, yet again, how batteries are an incredibly crucial strategic industry that much of the world has neglected. And it’s another example of how export controls are emerging as one of the most powerful tools of geoeconomics.

It also shows that despite all the BRICS talk, China views India as a strategic rival. China’s leaders are worried about India’s rise as a great power, given its huge size and its proximity to China. And since they view manufacturing as the font of all power — or at least, as their own key advantage — the idea that India could emerge as a rival manufacturing superpower keeps them up at night.

The United States, Japan, Korea, and Europe should see it as a core interest to make sure that India develops world-class manufacturing industries as soon as possible. Anything that keeps China’s leaders up at night is something that we probably want more of. Indians, of course, deserve the higher incomes and greater security that a world-class manufacturing sector would bring them.

3. Russia’s economy is suffering

Russia’s economy temporarily recovered from the initial dip it took at the start of the Ukraine war in 2022, and even grew at impressive rates of over 4% in 2023 and 2024. This prompted a lot of people to think that Russia’s economy had some sort of secret sauce — perhaps some combination of Elvira Nabiullina’s wise macroeconomic management and the mighty efforts of a nation pulling together to boost war production. It also prompted a widespread narrative that America and Europe’s sanctions on Russia were ineffectual.

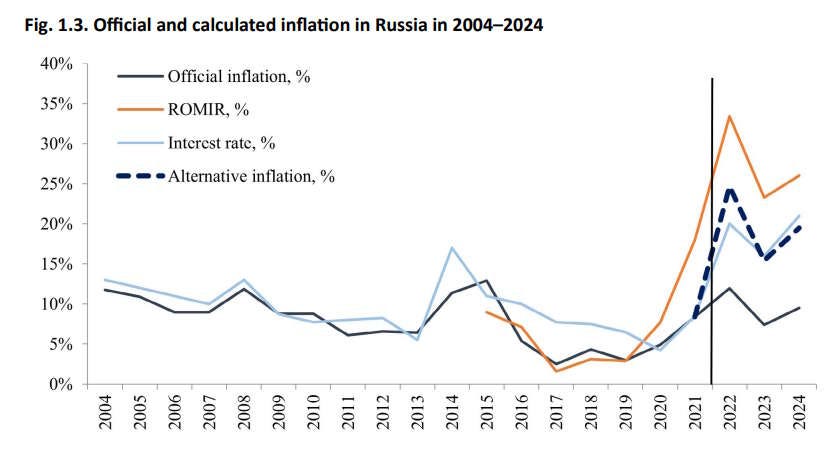

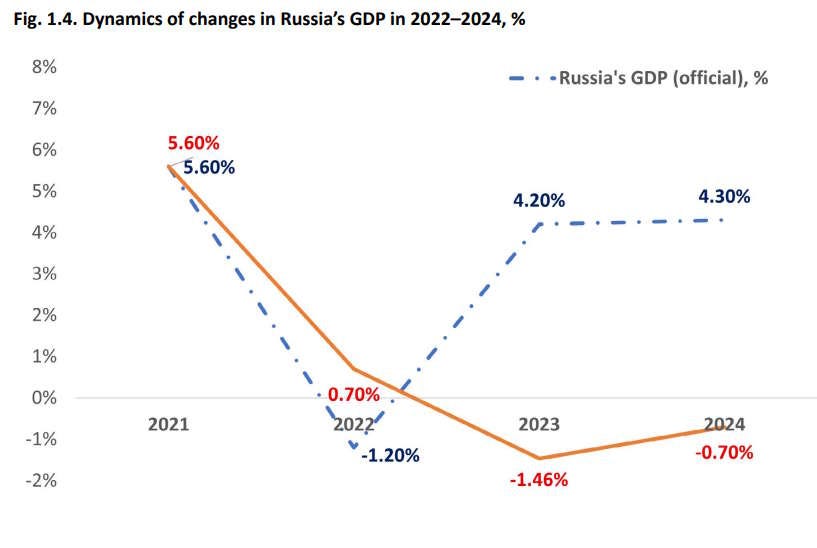

But perhaps there was less to Russia’s resilience than meets the eye. A recent report by PeaceRep alleges that Russia has been understating its official inflation figures by quite a lot. The authors argue that more realistic inflation numbers show that Russia’s economy has been shrinking, rather than growing, since the start of the war:

[O]fficial [Russian] statistics show an increase in GDP and the real i.e. inflation-adjusted incomes of the working population. According to official data, in 2021–2024, Russia’s GDP grew by +7.1%, and real household income grew by an unprecedented +24.8%. These figures are however based on questionable official estimates of inflation at between 7.4% and 11.9% per annum in 2022–2024. The very tight monetary policy of the Central Bank of Russia and the growth of the monetary supply imply this official rate is underestimated…The likelihood that the inflation rate is higher than publicly reported is further suggested by sources such as the analytical agency ROMIR, which until September 2024 monitored consumer inflation in Russia, estimated inflation in 2022 at 33%, compared to the official rate of 11%…For the present report an alternative estimate for the inflation rate in 2022–2024 was developed…The results showed that in this period Russia’s GDP fell by 1.5%, while real household incomes declined by 5.3%. [emphasis mine]

And here are two key charts:

Remember, the easiest way to overstate your country’s economic growth is to understate its inflation.

And remember that this data ends in 2024. In 2025, the Russian economy came under increasing strain, as oil prices continued to fall:

Ukraine, meanwhile, has been destroying many of Russia’s oil refineries with long-range drone strikes, and is now going after the tankers that let Russia sell crude oil to China. And as Martin Sandbu writes, all the natural strains of a wartime economy are beginning to add up — labor shortages, fiscal deficits, and so on.

Things will get increasingly tough for Russia’s economy if the war continues much longer. Whether that’s enough to get Russia to stop its campaign of conquest is anybody’s guess.

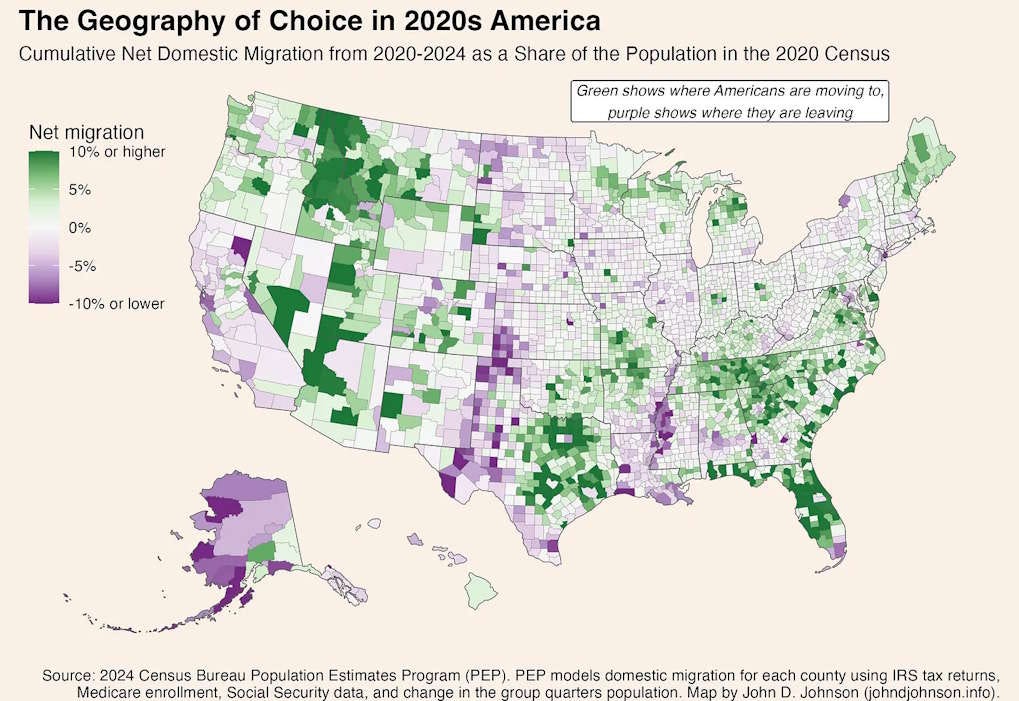

4. Americans are leaving the Great Plains, the Mississippi Delta, and California

John Johnson has a cool post about American domestic migration. Americans don’t move around much these days compared to the past, but there are some pretty clear patterns regarding where they’re moving away from and where they’re moving to:

Most notably, Americans are moving away from three regions:

California

The Mississippi Delta

The western Great Plains

It probably doesn’t take a genius to figure out why Americans are moving away from (2) and (3) here. The Mississippi Delta (technically the Mississippi Embayment) is America’s poorest region, and thus not a great place to live. The western Great Plains are devoid of thriving big cities, so there aren’t so many jobs, and people who want to live interesting urban lives tend to move elsewhere.

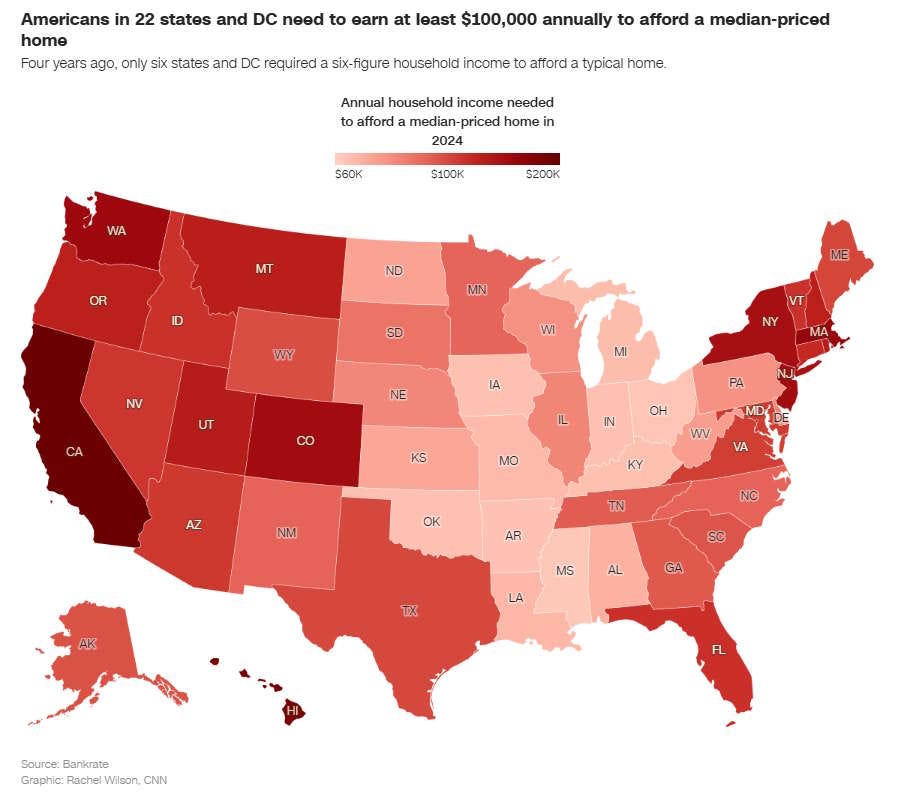

California is the real puzzler here — and the real tragedy. The conventional wisdom is that people are moving out of California because of high housing costs. Indeed, the state stands out on a map of house prices relative to income:

This pretty closely mirrors how much rent costs in each state.

What’s interesting is that New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey, where housing is almost as expensive, aren’t seeing big outflows right now. Maybe that’s because people already moved away in earlier decades, while Californians hung on for a while because of the nice weather.

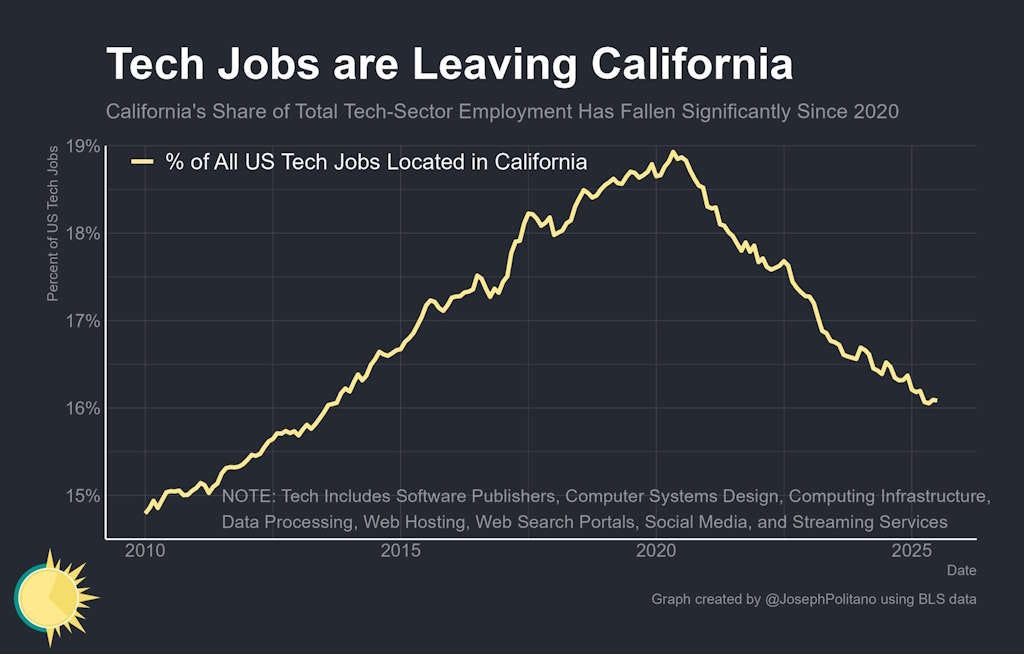

Another possibility, though, is that something is going deeply wrong with California’s economy. Since the pandemic, the state has been bleeding tech jobs:

This could be due to high housing costs driving people out of the state, or it could be due to the rise of remote work. Or it could be due to the tech industry’s clustering effect weakening, as clustering effects once weakened in manufacturing. In any case, it’s something California’s leaders ought to be very concerned about. The days when California could just bomb its residents with high housing costs and high taxes, and depend on sunny weather and clustering effects to keep everyone in the state, might be ending.

5. Why is hiring down?

Jed Kolko has an interesting thread about hiring. Employment rates are still high, but hiring rates have fallen off a cliff:

Jed argues that this is not due to either Trump or to AI:

It's not Trump policies, and it's not AI…Hiring has been very low since 2024, and has flattened out. If it were AI, the hiring slowdown would have accelerated in 2025, rather than plunging earlier. If it were Trump policy, the slowdown would have started in 2025.

I’m not sure either of those conclusions is warranted. It’s possible that companies could see how good AI was getting back in 2024, and held off on hiring out of caution about how much better it might get. This is just standard-looking forward expectations. On the other hand, it’s also possible that hiring would have rebounded in 2025 if not for Trump’s tariffs and immigrant deportations.

But anyway, Jed’s theory is that companies over-hired during the latter part of the pandemic — the bubble of 2021:

The pandemic broke the relationship between hires and unemployment. Pre-pandemic, low hiring = high unemployment. No longer. In pandemic recovery, there was lots of hiring, followed by a steep drop as some firms overhired…We are still feeling the effects of the pandemic.

That’s a plausible explanation, but as I said, I wouldn’t rule out either AI or Trump.

6. What development means for human beings

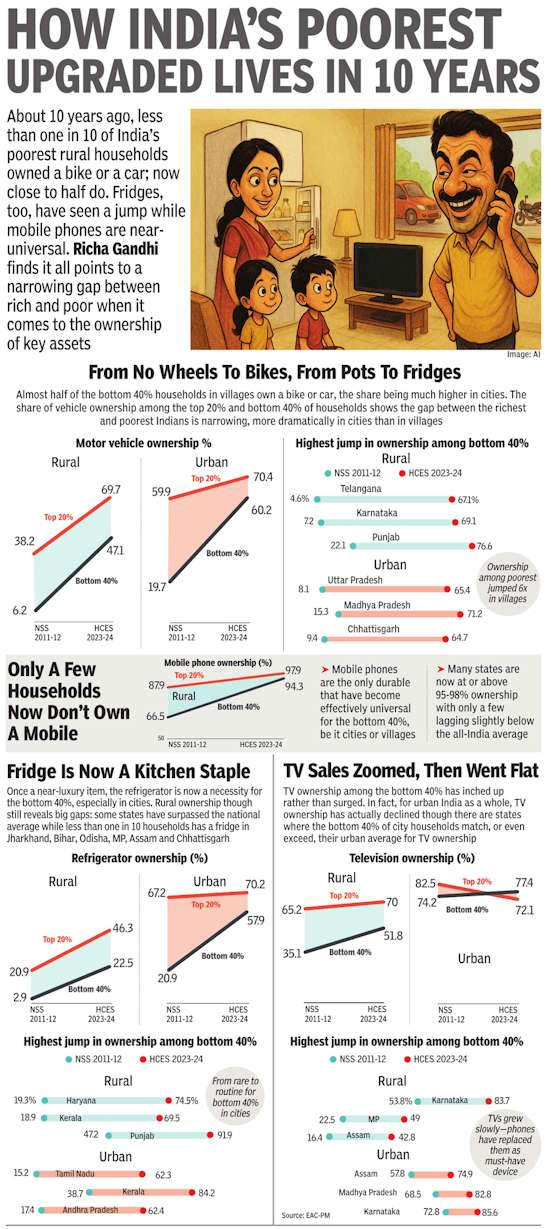

I’ve written a lot about Indian development, but I rarely talk about what this means for the people of India themselves, in human terms. But it’s really pretty incredible and transformative. Ravi and Penumarty have a new paper summarizing the changes in durable goods ownership in India from 2012 to 2024, which gives a fascinating peek into how economic growth is changing the life of regular Indians. Here’s an infographic based on their data:

Even relatively low-income people in India now tend to own a fridge, a motorbike (or car), a mobile phone, and a TV. That was not true a decade ago.

Remember, as much as certain smug intellectuals like to sneer at and dismiss the idea of economic growth and of GDP, for people in poor countries, GDP is everything, and growth is the utterly transformative. India has been doing a good job of transforming its people’s lives, and it deserves our praise, encouragement, and support.

7. Wind will be a niche power source

I’ve often written about how nuclear power will be a niche power source in the future — not useless, but not the way we produce most of our electricity. It’s also worth mentioning that I think wind power will also be niche. A recent post by X user Cremieux sums up a bullet-pointed list of reasons why wind will probably be marginal in our final energy mix. Key excerpts:

The bad:

- Generation is…stochastic…not deterministic [like] solar which comes and goes at predictable intervals

- Decay half life is too long for short-term storage (batteries, most pumped hydro)

- Decentralization without robustness…depending on geographical circumstances very fragmented grid topology may ensue

- Very low power density, amassing too much wind power in a small area considerably lowers total harvest (see North Sea)

- Very high intensity in rare earth minerals…

- Rather mediocre synergy with nuclear (unlike PV)

- High transport requirements

Basically, you don’t know when the wind will blow, but you do know more or less when the sun will shine. You also can’t cluster windmills too close together, or you use up all the wind. Those are really the key factors that make wind problematic as a power source. To this I’d add that A) the scaling curve for wind is much shallower than the one for solar, meaning that solar will keep getting better and better relative to wind over time, and B) the total land use requirements for wind farms are huge, which makes siting and permitting difficult, even though you can use the land between the wind turbines for other stuff.

Ramez Naam, my favorite futurist, and the man who predicted the age of solar far in advance, agrees with Cremieux’s points, but argues convincingly that wind will retain an important niche role in our future energy mix:

The US has tremendously better wind resources on land than Germany or most of Europe…

Wind doesn't pair nearly as well as solar with short duration (hours) of storage. It does pair very well with natural gas, though, and ends up saving a lot in fuel costs…

As we electrify heat, the electricity system on almost every continent will move to having a peak of demand in winter as opposed to summer today (due to AC) for the US. That is a challenge for solar. Wind and solar and complementary over the scale of seasons. Wind is lowest in summer when solar is strongest. Wind is stronger in fall and winter, and at its strongest in spring.

So wind, like nuclear, will still have its uses.

8. A cool new experiment in science funding

Over the past decade, there has been a lot of work devoted to “metascience” — the idea that in order to re-accelerate scientific progress and make it cheaper, we ought to change the outdated way that we fund scientific research. The Institute for Progress has been at the forefront of documenting and pushing forward that intellectual enterprise.

Now, IFP’s Caleb Watney reports on a big initiative to turn some of those ideas into reality. The NSF is shifting some of its funding outside academia:

A new [National Science Foundation] initiative called Tech Labs will invest up to $1 billion over the next five years in large-scale long-term funding to teams of scientists working outside traditional university structures…

For most of the postwar era, federally funded science has been built around a simple model…small, project-based federal grants mostly to individual scientists…But the science that shapes our world, from particle physics to protein design to advanced materials, increasingly requires massive data sets, large integrated teams and sustained institutional support…

The current structure is built for discrete projects rather than missions. When research requires long-term continuity, interdisciplinary collaboration or substantial shared infrastructure, it’s often difficult for it to fit into this structure…Rather than funding isolated projects, the [Tech Labs funding structure] would provide flexible, multiyear institutional grants in the range of $10 million to $50 million a year to coordinated research organizations that operate outside the constraints of university bureaucracy. These could include university-adjacent entities such as the Arc Institute or fully independent teams with focused missions.

This is really promising, and I’m excited to see how it plays out.

But I’m also wondering if the rise of AI science will open up another parallel avenue for rapid innovation by lone scientists or small teams working outside the academy — such as when some people used AI to solve some difficult outstanding math problems this past week. Maybe the NSF should also try giving some people grants to see how far they can push ultra-fast small-scale independent research, too.

In any case, I’m just glad to see our institutions taking metascience seriously, and trying new things.

On the net out migration of the plains, this is a story I have lived and is not necessarily bad news. The county in Northwestern Minnesota where I was born is an agricultural breadbasket and yet the population peaked in 1940 while continuing to fall. All my life, 68 years, the vast majority of the residents have lived a comfortable life with all the modern amenities and good to excellent schools, so why leave. This really is a success story of the productivity explosion in farming since WW2 and a strong work ethic combined with good education. The labor needed per acre of farmland has dropped by 90% while yields per acre increased by 2 to 4 times. This is the classic job loss due to productivity. So what of the people? The vast majority of outmigration was and is not due to deprivation but opportunity. With good education and work ethic it was and is easy to leave the area for higher paying employment. Those who remain tend to be in farming at scale, in a business that taps into the economy outside the area, or simply choose to stay close to family. The two main drivers of out migration continue to be productivity in agriculture and a social/education foundation for success outside the area. Ironically those residents with below average education and skills have a higher net standard of living here than by migrating as housing costs especially are so much lower and the social safety net stronger than sunbelt states. How long can this go on? No one really knows but the urban/suburban magnet is still pulling strong.

Excellent to emphasize: "Remember, as much as certain smug intellectuals like to sneer at and dismiss the idea of economic growth and of GDP, for people in poor countries, GDP is everything, and growth is the utterly transformative. India has been doing a good job of transforming its people’s lives, and it deserves our praise, encouragement, and support."

and Indian progress has come with generally what the Lefty proggy sneer at as neo-liberal reforms loosening up the "License Raj"

Regarding Wind (speaking here as a real-world RE financier): that Twitter/X post opens with something stupid "I suspect the details might give away why the Trump administration seems so opposed to wind." - anyone suspecting that is giving idiotic levels of credence to an analytical coherence for Trump - he hates wind because he fought over it relative to a branded golf course and lost, and he's that petty and that dim. (there's zero economic policy rationality in actively sabotaging - notably via completely transparent and of dubious regulatory legality directives and orders - existing advancing wind asset developments even if one took an energy mix skepticism on wind.) such a suspicion is at best naive sane-washing if not at worse being an active dupe.

I think the overall neg side eval on wind there is excessive by far, although not untrue - certainly wind has a number of important scaling issues that solar PV doesn't and the asset-cost basis of wind installations has run into something of a wall in the way solar PV panels has not (also installation scaleability - harvesting more power (ceteris paribus) means taller mega-installs and the ability to cost-effectively scale that including the logistics of getting them in place is a much different problem than panels.

And some of his bads are... extremely dubious (intensity of rare-earths? Bad? Well amigo that's Elec Tech Stack )

Further the Poster later comment about wind & solar increasing system wide costs is... well suggestive of a person with a certain view as it were as a half-truth (depending).

I think there are legitimate points in there but there are a number of items that are quite to me deformed and questionable. [noting yes attributed to an anon German energy trader but follow-ups suggest more - not that the way Germany has done energy in past 15 years says great coherence, thanks to Grunen and some spinelessness of the general parties, as shutting nuclear