People are realizing that the Arsenal of Democracy is gone

Bringing it back isn't impossible, but it will be difficult.

“Let not the defeatists tell us that it is too late. It will never be earlier. Tomorrow will be later than today.” — FDR, December 1940

Imagine that you grew up and lived your whole life protected by an invisible, magical shield that kept out the armies of foreign conquerors. The shield had been there before you were born, and there was no reason to think it ever wouldn’t be there — it was simply a background fixture of your Universe. And then one day imagine that this invisible shield vanished. You wouldn’t notice right away. And the conquerors, lurking patiently behind that shield, might also take a while to realize that your land now lay open and vulnerable to their armies. You would go about your life for a while unaware that anything important had changed.

If you live in a democratic country, I worry that this pretty much describes the situation you’re in right now.

These days I think a lot about this chart:

Why did democracy go from a fringe form of government in 1944 to a system that governed half the world by 2010? Was it because democracy was more economically advantageous? Was it because people demanded more democracy as they got richer? Maybe. But maybe it was a lucky result of U.S. power. American war production crushed the fascist empires in World War 2 (including saving the USSR), defended the “free world” during the Cold War, and held “rogue states” in check afterwards.

Franklin D. Roosevelt was right — America really was the Arsenal of Democracy. One small table of WW2 production numbers from Wikipedia shows exactly how the war was won:

The U.S. was by far the biggest producer, building twice as many large ships as all other combatants combined, and at least twice as many aircraft as any other combatant. The country’s mighty auto, aircraft, and ship industries took a while to ramp up war production, but when they did, nothing on the planet could match them. Books like Freedom’s Forge and Destructive Creation will tell you the story of how this was achieved. And that industrial dominance carried over into the Cold War, bolstered by the addition of Germany and Japan — two other leading manufacturing nations — as U.S. allies. The Soviets could threaten the West with their nuclear arsenal, but when it came to war production, the free world could outproduce the communist world.

For the first time since before the world wars, that situation has changed. The rise of China as a manufacturing powerhouse to rival the U.S. and all of Europe combined was always going to present a major challenge. But the utter withering of the U.S.’ defense-industrial base since the turn of the century has made this much less of a contest. The balance of military production potential now lies firmly on the side of the autocratic powers.

That sounds like a startling claim to make. But here are three images from my recent post about the threat of war with China that make the point pretty clearly:

If the U.S. mightiest efforts can only produce 1/9th of the artillery shells we could build in 1995, and China can produce 200 times as many ships as the U.S., the Arsenal of Democracy that existed during WW2 and the Cold War is gone. Even if these figures are exaggerated by a factor of 3, it still means the Arsenal of Democracy is gone.

I am not a lone voice in the wilderness shouting about this. A lot of people in the commentariat are coming to the same realization. Here’s A. Wess Mitchell in Foreign Policy:

The United States is a heartbeat away from a world war that it could lose. There are serious conflicts requiring U.S. attention in two of the world’s three most strategically important regions…

The United States has fought multifront wars before. But in past conflicts, it was always able to outproduce its opponents. That’s no longer the case: China’s navy is already bigger than the United States’ in terms of sheer number of ships, and it’s growing by the equivalent of the entire French Navy (about 130 vessels, according to the French naval chief of staff) every four years. By comparison, the U.S. Navy plans an expansion by 75 ships over the next decade…

[Defending U.S. allies] won’t be possible unless the United States gets its defense-industrial base in order. Since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, total U.S. defense production has increased by a mere 10 percent—even as the war demonstrates the staggeringly high consumption of military ammunition in a major conflict.

Here’s Mackenzie Eaglen at the American Enterprise Institute:

The Pentagon recently released its annual report on China’s military developments and its findings are clear…our military struggles to keep up…

China has continuously outpaced the U.S. in shipbuilding capabilities and shipyard capacity…While China’s navy is expected to increase by nearly 20 percent in just a half-decade, the Navy’s FY24 shipbuilding plan projects that it will keep getting smaller. Our fleet will shrink to 285 ships in 2025 and remain less than its size today, at 290 ships in 2030, as ship retirements consistently outpace new ship construction…

[T]he U.S. submarine fleet [is] expected to stand at just 57 boats in 2030…[T]he recent submarine depot maintenance backlog has rendered nearly 40 percent of the U.S. submarine fleet inoperable…Year after year the U.S. Navy remains saddled with shrinking and increasingly uncertain budgets.

Other articles to similar effect are popping up elsewhere, but you get the gist.

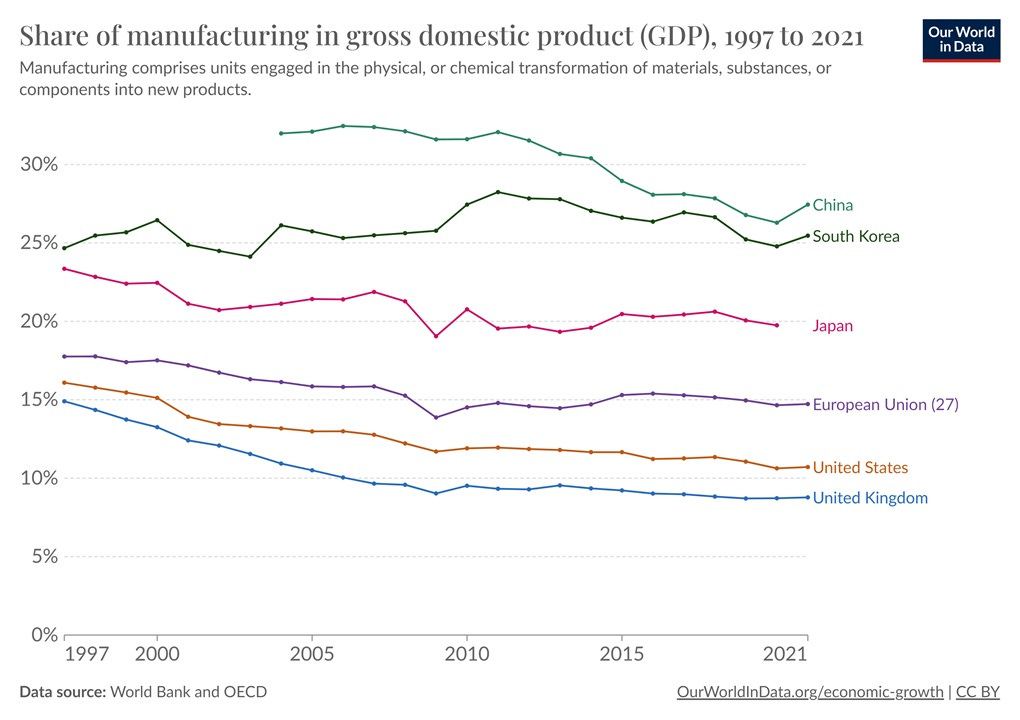

It’s important to clarify, by the way, that the phrase “Arsenal of Democracy” doesn’t refer to the size of our existing military, nor does it refer to our military spending. It refers to our military production potential — how much military equipment we could make in the event of a long conventional war against a major power like China. Although people who bemoan the withering of the defense-industrial base talk about shrinking military budgets, the deeper problem is the U.S.’ deindustrialization. Over the past two decades, less and less of the U.S.’ economy has been devoted to making physical stuff, while China’s economy has remained more industrial than any major U.S. ally:

Manufacturing isn’t the only thing you need for a strong military — software, logistics, and other things also help. But most of the economic output that goes into fighting a war consists of physical weapons and supplies. For years, pundits in the U.S. dismissed the importance of manufacturing, arguing that service industries like health care and education were more important sources of the good jobs of the future. Whether or not that was true, it completely neglected the military importance of manufacturing. This blase attitude toward deindustrialization has now come back to haunt us.

Anyway, I’ll talk a bit about how we might be able to restore the Arsenal of Democracy, but first, I think it’s important to explain why it matters in the first place. Obviously if you’re in Poland or South Korea, U.S. power and protection matter to you a lot. But many Americans naturally feel like they’re protected by oceans on either side, and can safely afford to ignore what happens to countries like Ukraine and Taiwan. This is disastrous complacency. If you’re not worried about the disappearance of the Arsenal of Democracy, you should be.

What the lack of an Arsenal of Democracy means for your future

One huge hurdle faced by Franklin D. Roosevelt in his effort to stop the Axis was the isolationism that prevailed among the American public at the time. The notion that America should stay out of foreign conflicts and sit serenely behind its two oceans was incredibly widespread, and the Roosevelt administration worked hard to convince their people otherwise. In a series of films entitled Why We Fight, the government argued that after the Nazis and the Japanese Empire subdued all enemies in their own back yard, they would eventually invade and conquer the U.S. The argument was basically that we could fight them there, or fight them here. In his “Arsenal of Democracy” radio broadcast, Roosevelt made this argument explicitly:

If Great Britain goes down, the Axis powers will control the continents of Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and the high seas — and they will be in a position to bring enormous military and naval resources against this hemisphere. It is no exaggeration to say that all of us, in all the Americas, would be living at the point of a gun — a gun loaded with explosive bullets, economic as well as military. We should enter upon a new and terrible era in which the whole world, our hemisphere included, would be run by threats of brute force.

Whether this was true is open to historical debate. In the present day, however, it’s unlikely that China and Russia would have much interest in physically conquering the territory of the United States. There’s just not much economic or political upside to doing that. But it’s likely that if the U.S. sat back and allowed China and Russia to become masters of all Eurasia, they would have the ability to weaken and impoverish America without explicitly conquering it.

One way to do this would be to cut off the U.S.’ trade. The U.S. is an unusually self-sufficient economy, but that’s a very relative statement — it still depends pretty crucially on things sourced from overseas. We could learn to make our own semiconductors and electronics and auto parts, but sourcing critical minerals entirely from within North America would be extremely difficult.

In addition, cutting the U.S. off from the global trade in manufactured goods would be incredibly disruptive. The U.S. imports $2.73 trillion worth of goods and services every year, and less than a fifth of that is from China. If you think the post-pandemic inflation was painful, imagine the inflation if the U.S. was unable to buy products from Europe, Japan, Korea, etc. It would not be fun. Nuclear weapons would be absolutely no defense against this sort of slow squeeze.

And China and Russia would have every motivation to weaken the U.S.’ economy as much as possible and as permanently as possible, simply because this would remove the U.S. as a potential threat. Neither one of America’s rivals would forget how the Arsenal of Democracy had kept them at bay for many decades; they would both want to make sure that a reinvigorated America could never threaten them again. They would seek to eliminate American power not because they hate us and our freedoms, but simply because this would neutralize a potential long-term threat.

The U.S. was ambivalent about whether it made sense to weaken and hobble Russia after the Cold War, ultimately deciding against it. China and Russia would not be so kind after winning a decisive victory in Cold War 2.

Isolationism would also expose the U.S. to encirclement by Chinese and Russian military bases, just as the U.S. and its allies sought to contain the communist powers during the Cold War, but likely with far greater ruthlessness. With mastery of Eurasia, China and Russia would take steps to make sure America’s isolationism went from voluntary to mandatory, ensuring that the U.S. would never again be able to project power in defense of its own security outside its borders. In other words, the U.S. would be in a cage. If terrorists attacked, the U.S. would be unable to retaliate overseas; if China felt like it should own Hawaii, there would be no way to stop it short of nuclear war.

Even worse, a supine U.S. would find it difficult to maintain our own democratic form of government. If China and Russia decided that a disarmed and economically isolated U.S. should be ruled by their puppet dictator, how effectively could the U.S. resist that pressure? And if China and Russia decided that freedom of speech in the U.S. might eventually lead to the rise of an American government that wanted to challenge their mastery, how easy would it be to keep our newspapers and websites free of their control?

In other words, the U.S. would not need to be explicitly conquered by Chinese and Russian boots on the ground in order to suffer grave negative consequences. Roosevelt talked about how the world had become smaller since the invention of aircraft. Now, in the days of the internet, cheap space flight, and long-range hypersonic missiles, the oceans are little defense at all.

So maintaining a robust system of global alliances, capable of resisting domination and conquest by China and Russia, is essential. Without it, the U.S.’ future will be a whole lot bleaker. And the U.S. military production potential that Roosevelt called the Arsenal of Democracy is crucial for maintaining that system.

How to restore the Arsenal of Democracy

The most important question, of course, is how the Arsenal of Democracy can be restored from its withered state. It won’t be easy — it wasn’t even easy back in World War 2. But there are a number of things that can be done.

In the short term, we can use tools like the Defense Production Act to increase capacity. A. Wess Mitchell writes:

The situation is serious enough that Washington may need to invoke the Defense Production Act and begin converting some civilian industry to military purposes. Even then, the U.S. government may have to take draconian steps—including the rerouting of materials intended for the consumer economy, expanding production facilities, and revising environmental regulations that complicate the production of war materials—in order to get the U.S. industrial base prepared for mobilization.

The DPA could help the U.S. address specific manufacturing bottlenecks as they crop up, such as the shortage of solid rocket motors. The Biden administration has already shown a willingness to use the DPA to produce green technologies like heat pumps, and the pandemic also normalized the use of the DPA, so this is a very realistic option.

A second short-term step is to leverage allies’ capabilities; our allies should also be part of the Arsenal. China’s mighty shipbuilding industry builds about half the ships in the world, but South Korea and Japan also build quite a lot, and they do it quite efficiently. We could outsource some naval production to these nations, but it would require repealing the Jones Act, which says that Navy ships have to be built and serviced in the U.S. by Americans. Meanwhile, the U.S. should exert diplomatic pressure on Europe — especially Germany — to overcome their own production hurdles and begin producing masses of ammunition and equipment to guard against Russia.

In the medium term, the U.S. needs to do several things. One is to revive the domestic commercial shipbuilding industry, which would be crucial in any ramp-up of naval production. I’ll write another whole post about how to do that, since it’s a long topic that deserves an in-depth treatment.

Another key task is to build a domestic drone industry. The Ukraine war has taught us that traditional weapons like tanks and manned aircraft won’t be enough to win modern high-tech wars — you also need drones in very large quantities, both to spot enemies and to destroy them. China dominates drone production. The U.S. has a bunch of drone startups like Anduril and Skydio, but these companies are hobbled by the fact that the defense market is very small in peacetime and the commercial market is dominated by cheap Chinese products. To rectify this, the U.S. needs an industrial policy act — an equivalent of the Inflation Reduction Act or CHIPS Act but for drones. This would create a long-term consumer-side and producer-side subsidy regime, coupled with substantial “buy American or allied” provisions for those subsidies.

On top of that, the U.S. needs a general military modernization. The world of military technology is changing very quickly, with rapid advances in fields like autonomous weapons, space weapons, hypersonics, lasers, advanced submarine detection, cyberwarfare, advanced sensors, and lots of other stuff. The U.S. will need to direct university research efforts toward these technologies, as well as leveraging the startup ecosystem. But it will also need to fund procurement, because without a guarantee of demand, new startups with fancy new technologies won’t be able to scale up.

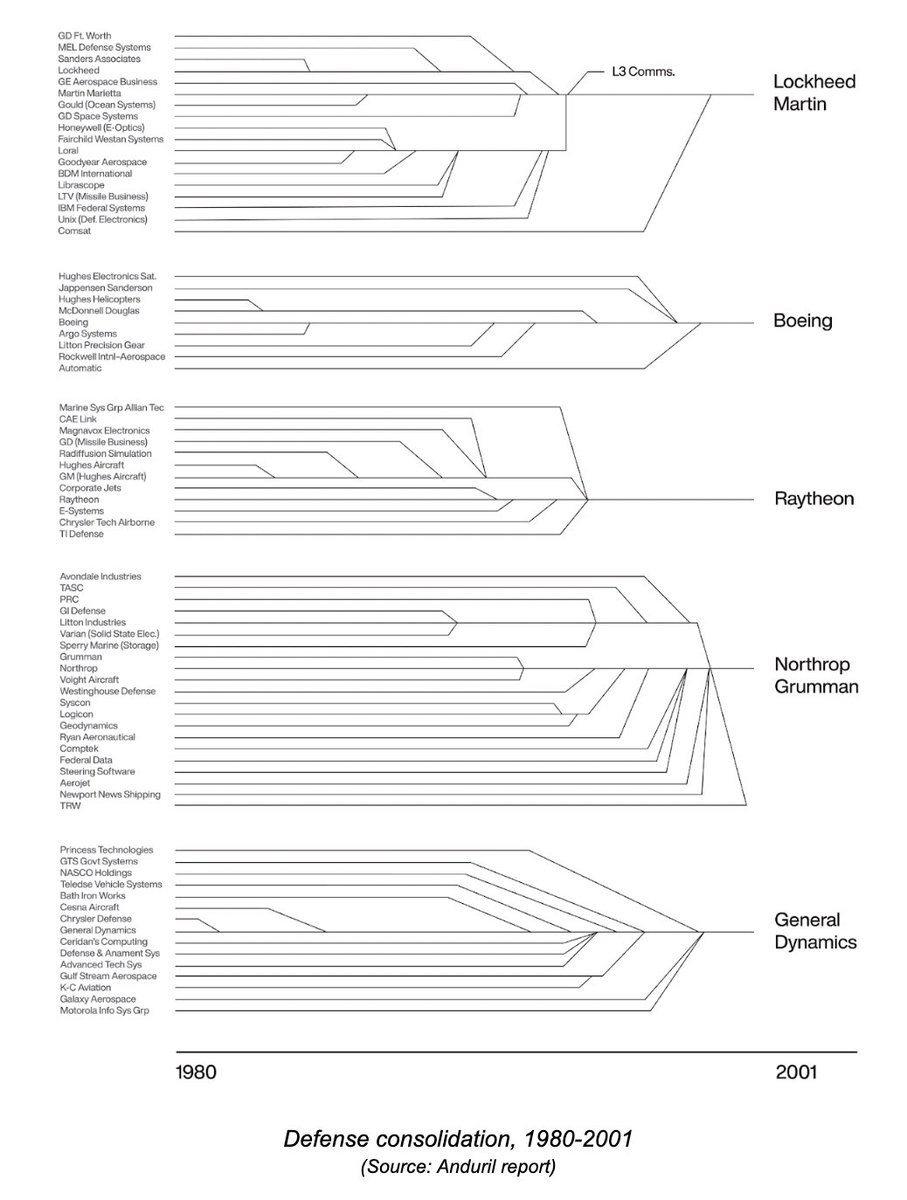

That brings me to perhaps the most important medium-term change. The U.S. badly needs to reform its defense contracting process. Pretty much everyone agrees that the domination of U.S. defense contracting by big monopolies like Raytheon since the end of the Cold War has been a disaster for defense procurement. Here’s a pretty eye-popping chart that’s been making the rounds:

Consolidation of the defense industry doesn’t just stifle innovation; it creates bottlenecks in the production process and makes it very difficult to surge production in a crisis. The devastation of the base of small defense manufacturers has hollowed out the workforce and created bottlenecks. Nancy Benecki of the Defense Logistics Agency writes:

Key industrial readiness indicators are going in the wrong direction…In 1985, the U.S. had 3 million workers in the defense industry. That number is now 1.1 million workers and remains flat…From 2016 to 2022, DLA lost about 22%, or 3,000 vendors, according to agency data. Small businesses accounted for 2,300 of those losses. Overall, the Department of Defense lost 43.1% of its small businesses in the same timeframe.

The “primes” have also become politically powerful, basically forcing the Pentagon to order the kind of expensive “platform” systems — fast jets, fancy tanks, etc. — that create fat margins for big contractors but may be less useful in a real fight than in previous decades.

And the domination of defense contracting by the “primes” creates a perverse profit incentive — the executives of companies like Raytheon are compensated with stock, whose value depends on profit margins. Profit margins go up when big companies eliminate competition and increase their market power, but this comes at the expense of overall production and efficiency. There are also various perverse incentives and inefficient processes involved in competition for defense contracts, which you can read about in Paul Scharre’s book Four Battlegrounds.

How can defense contracting be fixed? There are lots of debates and various viewpoints, but two suggestions that I see repeated very often are 1) switching to multiyear competitive contracts, and 2) sourcing the same or similar products from multiple suppliers.

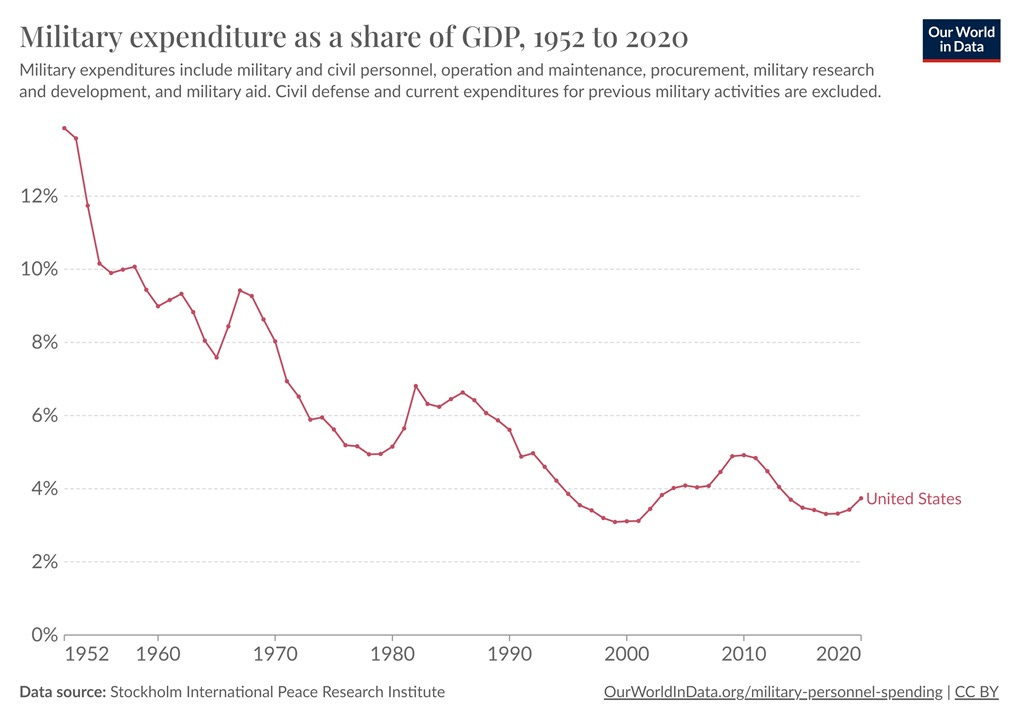

Of course, everything I’ve just mentioned is going to cost money. The U.S. spends a lot less of its GDP on defense than it used to:

Increasing defense spending is going to be necessary for reviving the Arsenal of Democracy. That doesn’t mean it’ll be sufficient; we still have to spend the money wisely instead of just hurling it at the big “prime” contractors, overspending on expensive traditional “platform” weapons, etc. We can spend our current military budget in much more efficient ways, and we can loosen regulations that make it hard to build things cheaply. But if we want to build our navy back up, increase ammunition production, revive the domestic shipbuilding industry, build a commercial drone industry, research cutting-edge technologies, and guarantee demand for a whole new ecosystem of small defense manufacturing subcontractors and high-tech startups, you can bet it’s going to cost some money.

And this money will have to come at a time of greater pressure for fiscal austerity. High interest rates and the specter of an inflation resurgence are forcing the government to tighten its belt. Thus, new military spending is going to have to come from some combination of higher taxes and reduced spending on things like health care. Neither of those is going to be incredibly popular with the citizenry, so this shift is going to take Rooseveltian leadership and a lot of bipartisan salesmanship.

At this point you may ask: Doesn’t the U.S. already spend a vast amount on its military? Well, yes, but most of that goes to things that aren’t incredibly useful for rebuilding the Arsenal of Democracy. Paul Poast explains:

Somewhat paradoxically, however, the massive level of U.S. defense spending isn’t enough: The U.S. military appears to be running short of ammunition…[I]t’s critical to understand that, despite the vast size of the defense budget, procurement of new weapons is a small portion of spending. The Defense Department and the various branches of the U.S. armed forces are an enormous bureaucracy. Roughly a quarter of the annual defense budget goes toward pay and benefits for personnel, and the largest portion of the defense budget is geared toward operations, training and maintenance. Procurement as well as research and development are only about a third of the budget.

This suggests another avenue of cost savings: Limit the U.S. military’s operations and deployments. Spend less on showing force and policing small conflicts around the world, and use the savings to focus on preparing for the potential big fights that could topple the world order.

As for the long term future of the Arsenal of Democracy, the U.S. simply needs to make manufacturing a more important part of its economy. Industrial policies like the IRA and the CHIPS Act are a good start, but this will take a long time. Another key long-term goal should be the crushing of the NIMBYism that has made defense factories as difficult to build as solar plants or affordable housing.

So there are actually quite a few things the U.S. can do to at least partially restore the invisible shield that protected our way of life throughout much of the 20th century. The question is whether a bitterly divided country like ours can muster the will to pay the necessary costs, make the necessary changes, and upset the necessary incumbents. In the past, national security was enough to motivate the American people to change their economic system; hopefully that will still work in the 21st century. If not, it will mean that the true Arsenal of Democracy — the American people’s willingness to defend themselves, their freedoms, and their world — has been depleted.

Beautifully researched and presented, thank you. We have a defense industry that is like the US healthcare sector - twice as expensive as everyone else's and half as effective. Restoring competition is going to be tough but critical...

As I keep pointing out, ships are a waste of money. Ukraine had a (small) navy which was sunk or captured on Day 1 of the Russian invasion. Despite this loss, Ukraine has inflicted a crushing defeat on the Black Sea Fleet, which was the subject of numerous chinstroking articles before 2022. Building a billion dollar boat that can be sunk by a million dollar missile is a really dumb idea. Let the Chinese do that, and send Taiwan lots of missiles.