Nations don't get rich by plundering other nations

National wealth comes from ingenuity, hard work, good institutions, sound policy, political stability, and openness to foreign ideas and investment.

One idea that I often encounter in the world of economic discussion, and which annoys me greatly, is that nations get rich by looting other nations. Here are just a couple of examples I saw today on the platform formerly known as Twitter:

This idea is a pillar of “third world” socialism and “decolonial” thinking, but it also exists on the political Right. This is, in a sense, a very natural thing to believe — imperialism is a very real feature of world history, and natural resources sometimes do get looted. So this isn’t a straw man; it’s a common misconception that needs debunking. And it’s important to debunk it, because only when we understand how nations actually do get rich can we Americans make sure we take the necessary steps to make sure our nation stays rich. (There actually are some more sophisticated academic ideas along similar lines, and I’ll talk about those in a bit.)

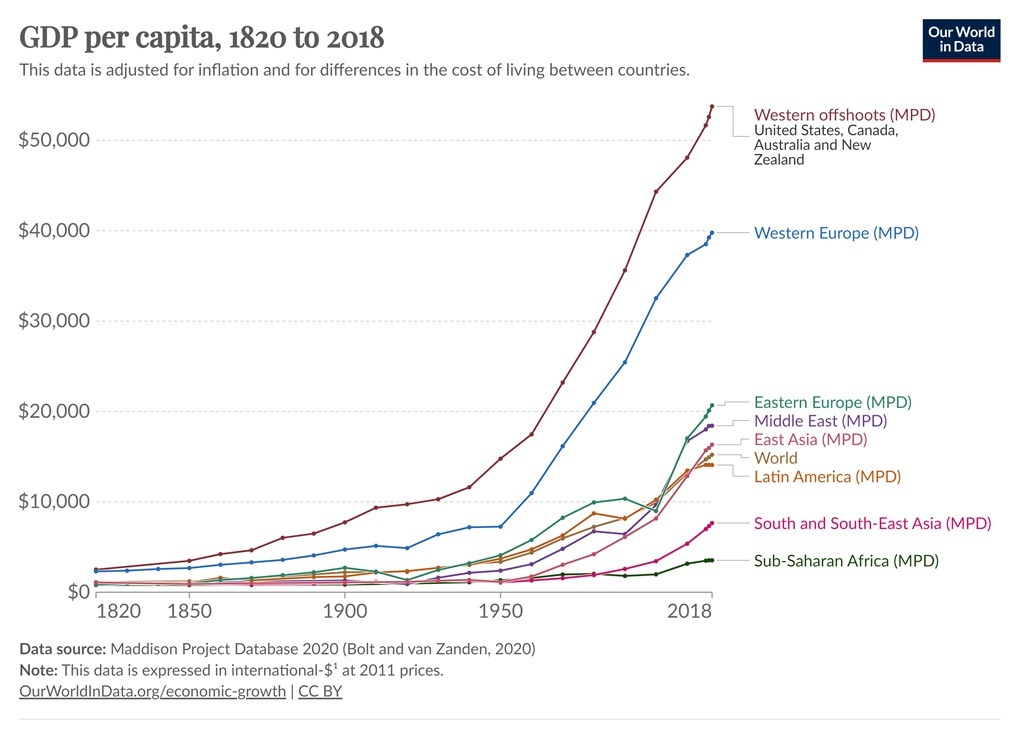

So anyway, on to the debunk. The first thing to notice is that in the past, no country was rich. There’s lots of uncertainty involved in historical GDP data — plenty we don’t actually know about populations, prices, and what people consumed in those eras. But even allowing for quite a bit of uncertainty, it’s definitely true that the average citizen of a developed country, or a middle-income country, is far more materially wealthy than their ancestors were 200 years ago:

If you account for increasing population and look at total GDP, the increase is even more dramatic.

What this means is that whatever today’s rich countries did to get rich, they weren’t doing it in 1820. Imperialism is very old — the Romans, the Persians, the Mongols, and many other empires all pillaged and plundered plenty of wealth. But despite all of that plunder, no country in the world was getting particularly rich, by modern standards, until the latter half of the 20th century.

Think about all the imperial plunder that was happening in 1820. The U.S. had 1.7 million slaves and was in the process of taking land from Native Americans. Latin American countries had slavery, as well as other slavery-like labor systems for their indigenous peoples. European empires were already exploiting overseas colonies. But despite all this plunder and extraction of resources and labor, Americans and Europeans were extremely poor by modern standards.

With no antibiotics, vaccines, or water treatment, even rich people suffered constantly from all sorts of horrible diseases. They didn’t have cars or trains or airplanes to take them around. Their food was meager and far less varied than ours today. Their living space was much smaller, with little privacy or personal space. Their clothes were shabby and fell apart quickly. They had no TVs or computers or refrigerators or washing machines or dishwashers or toasters or microwaves. At night their houses were dark, and without air conditioning they had trouble escaping the summer heat. They had to carry water from place to place, and even rich people pooped in outhouses or chamberpots. Everyone had bedbugs. Most water supplies were carried from place to place by hand.

They were plundering as hard as they could, but it wasn’t making them rich.

Nor were colonized and exploited nations and peoples rich before the European empires arrived. Yes, Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia were harshly exploited by European empires for their natural resources. But although Africa, Latin America, and Asia were closer to Europe in terms of living standards back then, they were all very, very poor by modern standards.

This should be the first very strong clue that modern rich nations’ wealth didn’t come primarily from plunder, but from something else — something that nations started doing over the last century and a half. In fact, we know what that something is — it’s industrial production, coupled with modern science.

We are far richer than our ancestors because we know how to make a lot more stuff than we did then — cars and trains and planes and antibiotics and vaccines and reinforced concrete and electricity and running water and TVs and computers and all the rest. And we know how to make stuff more efficiently. In 1810, 0.4 percent of Americans’ income was spent on nails. Yes, you heard that right — the little metal pointy things took $1 out of every $250 we earned. Nowadays it’s negligible. In 2006, the price of lighting in the UK was about 1/4500 the price of lighting in 1786.

So the fabulous wealth of the modern day can’t be due to plunder alone. The world does not contain a fixed lump of wealth that gets divided up among the people of Earth. Human ingenuity and hard work increases the amount of wealth in the world.

Anyway, there are two more sophisticated cases you can make for the “imperial plunder” theory of national wealth. The first is that continuing plunder is responsible for income differences between countries. The second is that plunder was necessary to initiate the process that eventually led to industrial production and modern science. The first of these arguments is wrong; the second can’t easily be disproven, but there’s major reason for doubt.

“Neocolonialism” and resource extraction

Some people allege that the reason the U.S., Europe, and East Asia are rich is because they exploit resource-exporting countries. This is part of a wider theory known as “neocolonialism”. The usual argument is that rich countries maintain influence over the governments of resource-exporting countries that allow them to pay artificially low prices for those countries’ products. For example, the book Confessions of an Economic Hit Man details methods by which the U.S. allegedly interferes in poor nations’ politics, by offering them loans that then trap them into a cycle of dependency. (Similar allegations have been made against China more recently.)

But how much wealth can this really transfer? A leading public proponent of the neocolonialist hypothesis is Jason Hickel, the British anthropologist who has become famous for claiming (wrongly) that global poverty hasn’t fallen, and for promoting the (bad) idea of degrowth. In a 2021 paper with Dylan Sullivan and Huzaifa Zoomkawala, he writes:

This paper quantifies drain from the global South through unequal exchange since 1960. According to our primary method, which relies on exchange-rate differentials, we find that in the most recent year of data the global North (‘advanced economies’) appropriated from the South commodities worth $2.2 trillion…Appropriation through unequal exchange represents up to 7% of Northern GDP and 9% of Southern GDP.

Even if this were correct, 7% of the GDP of rich countries is not a lot. Making the U.S. and Europe and East Asia 7% richer would have a noticeable impact, but it wouldn’t change the basic pattern of wealth and poverty among the nations of Earth.

That said, there are reasons to suspect that the methodology Hickel et al. use is not right. They calculate net transfer of resources — including labor as a resource — using a method by Dorninger et al. (2021). This method basically just shows that developing countries A) are net resource exporters, and B) are net labor exporters. But this is common knowledge already. Poor countries are less technologically sophisticated, so their exports will tend to have more raw materials and be more labor-intensive. Rich countries have better technology and more capital (machines, vehicles, structures, etc.), so their exports will tend to be more capital-intensive and technology-intensive.

That doesn’t mean exchange is unequal. Here, let’s imagine a simple example. Suppose I have a machine that makes wood into bookshelves, and you want a bookshelf but you don’t know how to make one. So you go spend an hour chopping down a bunch of wood, and you give it to me. I spend 15 minutes running half of that wood through my machine, which turns it into a bookshelf, and I give you the bookshelf. I keep the other half of the wood for myself.

Did I rip you off? No! Sure, the thing I traded you (the bookshelf) contained less wood and required less labor than the thing you traded me (the raw wood). But you’re happy with the trade, because now you have a bookshelf that you couldn’t have easily produced yourself. And I’m happy too, because I have some extra wood. There was an unequal exchange of resources and labor, but it was balanced out by the value added by my advanced technology and my capital equipment.

So the theory used by Hickel and his coauthors appears to be the old Marxist labor theory of value, with natural resources tacked on in addition. The problems with that theory are well-known.

Next, there’s the question of exactly how rich countries achieve this supposedly unequal exchange. During the era of colonialism, imperial powers could pay their colonies artificially low prices for their raw materials. But now, commodity prices are generally set on the world markets — there are a few differences related to shipping costs and storage costs and things like that, but in general, the price of copper Chilean miners get is going to be about the same as the price American or Australian miners get. Rich countries might use dirty tricks to lower the global price of commodities that they’re net importers of, but they’d have to be willing to hurt their own miners too.

And this would also involve screwing over rich countries like Australia that are primarily commodity exporters. Australia is very obviously not a poor country, so if we’re screwing over Australia through suppression of global commodity prices, we’re not doing it very much.

The easier thing to do, by far, would be to push poor resource-exporters to undervalue their exchange rates. This would allow rich countries to pay less for those nations’ exports, simply because a U.S. dollar or a euro would be able to buy more. This is the mechanism that Hickel et al. (2021) claim is being used to carry out neocolonialist resource extraction.

But does this make any sense? Models of currency undervaluation and overvaluation are all over the place — I’ve seen assessments that Brazil’s exchange rate is overvalued and others that say it’s very undervalued.

The idea that commodity exporters chronically undervalue their currencies also doesn’t fit with the recent history of these countries. Commodity-exporting nations are known for overvaluing their own exchange rates, in order to afford more imports. This is why you always see emerging-market currencies crash in a crisis — the chronic overvaluation couldn’t last forever.

But perhaps you could claim that the currency crises themselves — which are often provoked by external borrowing — are sneaky “economic hits” carried out by the rich countries. Maybe the U.S. and Europe entice poor countries into borrowing too much dollar-denominated or euro-denominated debt, just so they can crash those countries’ currencies and buy their commodities on the cheap!

Some countries, like China, do try to deliberately undervalue their currencies. If you really want, you can tell yourself that this is neocolonial policy — China keeping the yuan weak in order to sell their labor at cut-rate prices to their American overlords. In fact, the late David Graeber did make a claim like this. The only problem with this claim is that it is utterly ridiculous. The U.S. government has long pressured China to strengthen the yuan, in order to make Chinese exports less competitive, and China has steadfastly refused. China maintained (and possibly still maintains) a weak yuan in order to pump up its exports, which it feels is helpful for its national development.

So anyway, the exchange rate mechanism for neocolonialism doesn’t make a lot of sense in general. If you think specific emerging-market currency crises were engineered by rich countries in order to grab cheap resources, then fine — I can’t prove you wrong (and Hickel et al. can’t prove you right, either). But in general, when developing countries hold their currencies down over long periods of time, it’s to pump up their exports, because they feel this is in their interest.

Note that none of this means extraction of cheap resources is impossible. A mechanism that the modern-day neocolonial theorists don’t discuss much is market power. The saga of Botswana and De Beers is an example of this — over time, Botswana has successfully pressured De Beers to let the country keep more and more of the diamonds mined there. This shows a shift in market power from a Western company to a local African resource exporter, to the benefit of the latter. So it is at least occasionally possible for resource exporters to force Western companies and countries to give them a better deal.

But it just doesn’t look like neocolonialist resource expropriation is what’s keeping rich countries rich and poor countries poor.

Did colonialism and/or slavery cause the Industrial Revolution?

A more subtle and difficult-to-disprove argument is that imperialist expropriation in the 1800s caused the Industrial Revolution, which then enabled today’s rich countries to become rich. In other words, the argument is that even if imperialism and colonialism didn’t make Europe or the U.S. rich by modern-day standards at the time, it set a process in motion that eventually snowballed into the thing that made those countries rich eventually.

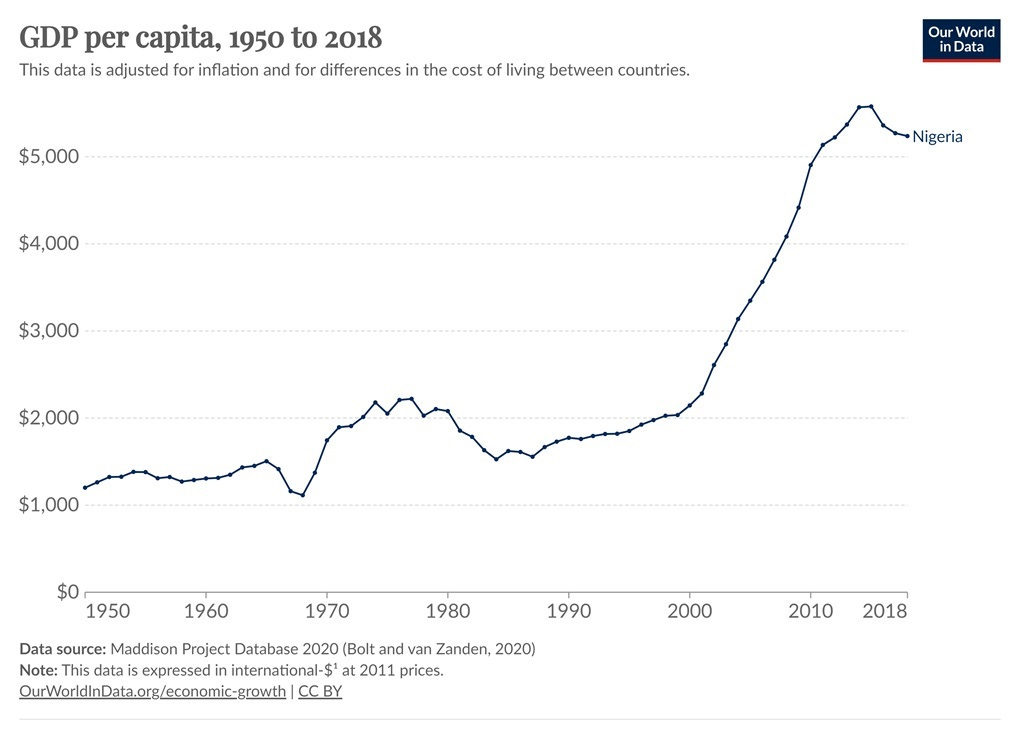

First, we should realize the logical implications of that argument. Almost all of the countries of the modern-day Global South — Africa, Latin America, South Asia, and the Middle East — are far richer than they were in 1820. For example, take Nigeria. Nigeria is a very poor country, and one of the world’s worst growth performers. Nevertheless, it’s now about five times richer than it was in 1950:

A big reason Nigeria is richer than before is through their economic interactions with the rich countries of the “Global North”. This includes technology transfer — some Nigerians can now drive cars because Germany invented the car, most Nigerians have phones because America invented the phone, and so on. It also includes trade — Nigeria sells oil to the rich world, and whether or not you believe its exchange rate is too low, these exports are a very substantial source of earnings that Nigeria uses to buy imports.

All of that was made possible by the Industrial Revolution. Had the U.S. and Europe and East Asia not industrialized, they would not have invented the cars and phones and other modern stuff that many Nigerians now enjoy. And they would not be able to pay nearly so much for Nigerian oil (in fact, they wouldn’t need the oil at all). So Nigeria would be a lot poorer today if the Industrial Revolution had never happened.

Therefore if you think colonialism and imperialist exploitation were necessary to kickstart the Industrial Revolution, then you have to believe that colonialism and imperialist exploitation led to the Nigeria of 2023 being five times as rich as the Nigeria of yesteryear.

I’m not saying this is wrong, but this would be the inevitable implication.

So anyway, did colonialism and imperialism cause the Industrial Revolution? The short answer is that no one knows, because no one really knows why the Industrial Revolution happened. We can only make slightly-educated guesses.

There is a popular theory that slavery in the U.S. caused the Industrial Revolution. This theory, championed by historian Ed Baptist, is very popular on the Left, and even made it into the New York Times’ 1619 Project. But it’s probably wrong. A lot of evidence shows that slavery is bad for the economy; one paper found it gave the economy a boost, but the size of that boost was very small. In general, both the historical evidence and the economic evidence is against this theory, so I’d put this in the category of “popular 2010s ideas that didn’t hold up”.

What about colonialism and imperialism in general? Here the case is more plausible, at least. A leading theory of the Industrial Revolution is that cheap resources and expensive labor prompted businesspeople to start substituting machine labor for human labor, sparking a self-sustaining wave of mechanical innovation. Artificially cheap resources from Europe’s colonies may have contributed to that imbalance.

And certainly, the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand never would have been rich without the imperialist act of conquering land from the previous inhabitants. Indeed, they would not exist at all.

That said, it’s pretty clear that imperialist extraction was neither necessary nor sufficient for a country to get rich. South Korea, Singapore, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Switzerland, and a number of other countries have gotten rich without ever having colonial empires, while Germany only had a small one for a very short time. Meanwhile, Spain and Portugal, which had vast and highly extractive colonial empires, were economic underperformers for a long time, and are still poorer than much of Europe.

So to tell a story about how colonial imperialism sparked the Industrial Revolution, you have to explain why it only worked for the UK and France. And then you have to tell a story where a small initial push from stolen resources in the 1700s and 1800s started the massive, self-sustaining, centuries-long process of global industrialization, most of whose benefits went to countries that didn’t do the initial exploitation (or any). You have to argue that this was a special one-time event, and that after that, imperialist exploitation stopped being necessary for a country to get rich.

And then after all that, you have to explicitly accept the implication that all the riches of modern life — the antibiotics and the vaccines, the abundant food and the towering buildings, the smartphones and the trains and your favorite Netflix show, were all made possible by that initial act of British and French imperialist exploitation.

All things considered, I think the more reasonable case to make is that wealth, generally speaking, is something that comes from a country’s technological ingenuity, hard work, sound policy, political stability, high-quality institutions, and openness to foreign ideas and technology and investment. Today, in 2023, wealth is a thing that nations create for themselves, not something they steal from other nations.

It's not that plunder let Western Europe get better technology, but that technology let Western Europe seize more plunder.

Premodern nations everywhere imposed tribute or took slaves from or just conquered weaker states. Europeans were no different. But modern guns, ships, and financing let Europe do to the whole world what people like the Aztecs or Manchus had only been able to do to their neighbors.

It's not like Spain needed American colonies to develop guns and ships and bankers. It's the other way around: by the 1500s, Spain already had superior enough tech to conquer Mexico and Peru with tiny bands of well-timed conquistadors. The technology came first, and made the great plundering possible.

We forget, now, how much technology had already advanced in Europe by 1800, or even by 1500. It wasn't important for everyday standards of living yet, so it doesn't show in per capita income charts. But if you lived in London or Amsterdam of 1700, or even Florence of 1500, you were in a city decked with engineers and manufacturers who could sell you things that nobody could buy in India or China or the Americas. That technology wasn't making ordinary peasants better off yet, but it was already reshaping long-distance travel, and business – and war.

Ironically, the same technology that enabled so much plundering was making it unimportant. A rich ancient Roman was rich because he had many slaves working for him; conquest, and the extreme inequality that followed it, really was essential for wealth. But today we're rich because we own machines, not because we subjugate our neighbors. In fact free neighbors are worth more to us than slaves, because free neighbors are much more productive.

Capitalist growth, that leftists want to credit to plunder, is just what's made plunder no longer an important part of our world.

1) We need to be more honest that after Britain industrialized, most other countries got richer through utilizing IP from richer countries, reverse engineering, and then improving it. In the 18th century, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, endorsed stealing British inventions, reverse engineering them, and then make American versions. In 1791, the American government paid $48 ($1561 in 2023 money) to English industrialists to replicate inventions for the American market. That's how the North in the U.S. became industrialized before American became on the frontier of innovation itself. While the South was just exporting cash crops like cotton. Germany, Japan, and South Korea got rich the same way. Now China is getting rich that in the same way.

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/5-answers-to-questions-you-may-have

2) We now have a few (but not many) examples of former Vassals/colonies that surpass the metropole. Those former colonies/vassals got richer or became as rich either through winning the natural resource lottery with a small population (UAE or Qatar beating UK with having a lot of oil & gas), ingenuity and finding advantages, hardwork and etc. (Taiwan and South Korea are now equal or higher on a per capita ppp basis to Japan the former colonial master, Singapore > UK, Macau, through becoming a gambling state > Portugal), and of course US and Canada > UK or Poland & Baltic states > Russia.

3)I think it's obvious that the industrial revolution came from the continuation of manufacturing advances that Persian, Turkish, Mughal, Omani, Ming & Ching, and even perhaps even the Moroccan and more advanced African empires (Kongo, Songhay, etc.) made. The Europeans managed to trade with ALL of them, so the Europeans just continued their ideas and advance them with by developing an economic system that rewards risking capital (Dutch invented stock market) and values strong property rights protection British. Even in the 18th century, most of the world was basically feudalistic society with a King that abused property rights. Since that feudalism was dead in Western Europe since the bubonic plague, they were the first to end that type of society and make a new one. Meanwhile in Africa, Ethiopia, the only nation that avoided colonialization, was a feudalistic society where the Monarch controlled most of industry and the nobles discouraged some innovation to protect their wealth. Ethiopians were poorer than Congolese (which had a horrific colonial history with King Leopold and Belgians) until 2008.

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD?locations=ET-CD