In defense of science fiction

New technology is usually good, and it's good for sci-fi to inspire it.

As everyone who reads this blog knows, I’m a big fan of science fiction (see my list of favorites from last week)! So when people start bashing the genre, I tend to leap to its defense. Except this time, the people doing the bashing are some serious heavyweights themselves — Charles Stross, the celebrated award-winning sci-fi author, and Tyler Austin Harper, a professor who studies science fiction for a living. Those are certainly not the kind of opponents one takes on lightly! (And I happen to like and respect both of them.)

So yes, I’m still going to leap to science fiction’s defense, but I’m going to do it very carefully.

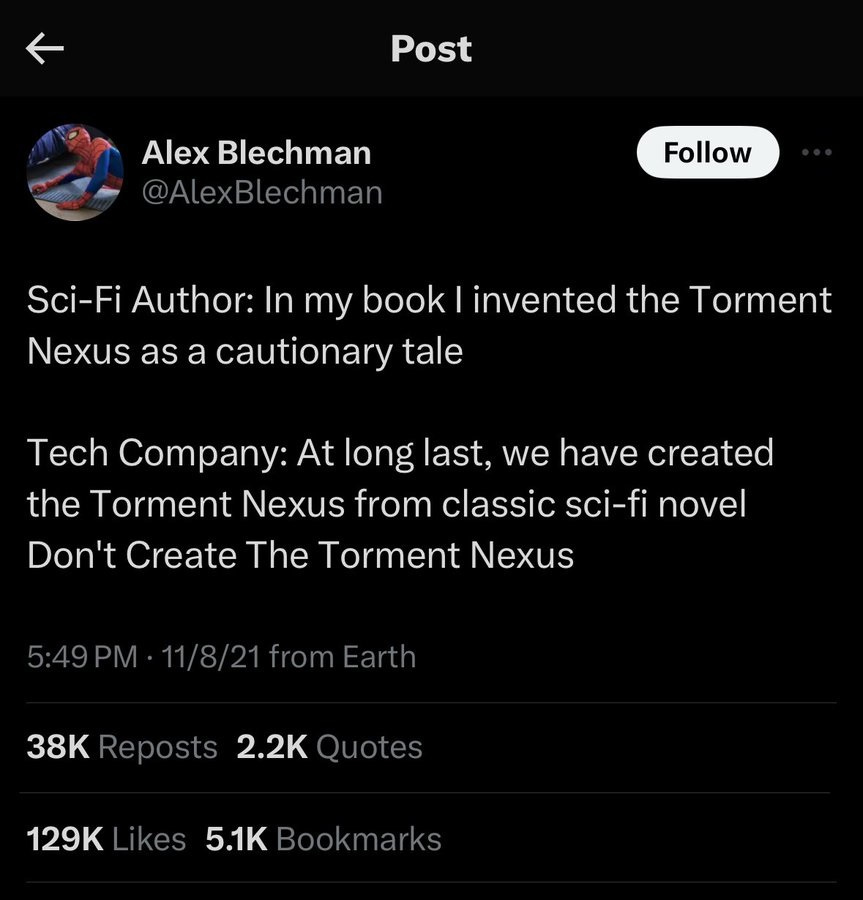

The two critiques center around the same idea — that rich people have misused sci-fi, taking inspiration from dystopian stories and working to make those dystopias a reality. Stross and Harper both reference this famous tweet:

Now, this kind of thing certainly happens with works of literature — after Michael Lewis wrote Liar’s Poker as a cautionary tale about the excesses of the 1980s bond trading industry, he was famously deluged with fans asking him how they could get into bond trading. So the idea is worth taking seriously.

Stross, however, seems to veer away from this argument into a very different one. In an article in Scientific American, he writes:

[Science fiction’s influence]…leaves us facing a future we were all warned about, courtesy of dystopian novels mistaken for instruction manuals…[T]he billionaires behind the steering wheel have mistaken cautionary tales and entertainments for a road map, and we’re trapped in the passenger seat.

But when he specifies the sci-fi-inspired technologies that billionaires are creating, it’s difficult to find any Torment Nexuses on the list:

Elon Musk wants to colonize Mars. Jeff Bezos prefers 1970s plans for giant orbital habitats. Peter Thiel is funding research into artificial intelligence, life extension and “seasteading.” Mark Zuckerberg has blown $10 billion trying to create the Metaverse from Neal Stephenson’s novel Snow Crash…

Sci-fi writers may set their external conflicts on a Mars colony or an orbital habitat — after all, writers need to have some sort of plot — but in general, these are associated with utopian sci-fi like Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy. In general, sci-fi authors and fans tend to think that humanity spreading throughout the cold dead vacuum of space, and bringing life to that vast lifeless space, is a good thing — a sign of a civilization that made it. So why bash Musk and Bezos for wanting to make it to the stars too?

Similarly, life extension and virtual reality are both generally portrayed as positive developments, rather than dystopian ones. Both create obvious challenges — life extension can lead to overpopulation and boredom, while people can get lost in VR worlds. But in general, people living longer and creating new worlds to explore are rightfully seen as good things, rather than dystopian Torment Nexuses.

Artificial intelligence is a common sci-fi trope, and sometimes it’s portrayed in horrifying, dystopian ways. But there are also plenty of positive, hopeful examples of AI in science fiction — R2-D2, Data and the holographic Doctor from Star Trek, WALL-E, the computer Mike from The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, and many others. The rich people working on AI definitely evince a desire to create “friendly” or “aligned” AI that will resemble these positive portrayals, and avoid “unaligned” AI that would resemble the cautionary tales of 2001: A Space Odyssey, “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream”, the Terminator and Matrix movies, and so on.

As for seasteading, I guess Neal Stephenson does make fun of it in Snow Crash. I must say, I’m not exactly staying up at night worrying about it.

So I think Stross really doesn’t come up with any credible examples of billionaires mistaking cautionary tales for road maps. Instead, most of his article focuses on a very different critique — the idea that sci-fi authors inculcate rich technologists with bad values and bad visions of what the future ought to look like:

We were warned about the ideology driving these wealthy entrepreneurs by Timnit Gebru…and Émile Torres…They named this ideology TESCREAL, which stands for “transhumanism, extropianism, singularitarianism, cosmism, rationalism, effective altruism and longtermism.” These are separate but overlapping beliefs in the circles associated with big tech in California…

The science-fiction genre that today’s billionaires grew up with…goes back to inventor and publisher Hugo Gernsback…His magazine’s strain of SF promoted the combination of the American dream of capitalist success, combined with uncritical technological solutionism and a side order of frontier colonialism…Gernsback’s rival, John W. Campbell, Jr…was also racist, sexist and a red-baiter.

This is almost diametrically opposite from the “Torment Nexus” critique. Instead of billionaires mistaking well-intentioned sci-fi authors’ intentions, Stross is alleging that the billionaires are getting Gernsback and Campbell’s intentions exactly right. His problem is simply that Gernsback and Campbell were kind of right-wing, at least by modern standards, and he’s worried that their sci-fi acted as propaganda for right-wing ideas.

This is a much simpler argument, but it’s also harder to evaluate. Where does the causality lie? Do right-wing billionaires arrive at their political convictions by reading right-wing sci-fi? Or do they simply prefer literature that’s aligned with their existing values? This is really hard to know. For what it’s worth, my impulse says it’s the latter — there’s such an ideological and stylistic diversity of sci-fi out there in the world that anyone who reads it widely will encounter a very wide range of political viewpoints. For every Robert Heinlein there’s an Ursula K. LeGuin, for every Vernor Vinge there’s an Iain M. Banks. Heck, there’s even a Charles Stross.

In other words, if billionaire tech entrepreneurs’ big take-away from sci-fi is that billionaire tech entrepreneurs are good, it’s probably what they went in wanting to hear.

Anyway, on to Harper’s similar critique. He starts it off quite boldly:

It’s fairly obvious that he’s being hyperbolic here — I doubt Harper really decided to devote his life to studying and thinking about science fiction because he thinks it’s a blight on society. But in any case, he followed this initial broadside up with a longer and more detailed thread, so let’s go to that.

First, Harper argues that sci-fi is not politically effective:

The question of whether literature has a political effect is an empirical one — and it’s a very difficult empirical one. It’s extremely hard to test the hypothesis that literature exerts a diffuse influence on the values and preconceptions of the citizenry. Perhaps we could use the imposition of some sort of censorship code, along with regional or demographic variation in pre- and post-censorship literature sales, as a natural experiment. But even then it would be hard to argue exogeneity, since censorship is a response to society’s values as well as a potential cause of them.

That said, there’s certainly evidence that news media itself does affect politics, and it’s not easy to see why literature and news media should be entirely different here. And there are some fairly convincing historical anecdotes in which fiction books like Uncle Tom’s Cabin seemed to affect the national political conversation. So the claim that sci-fi, or literature in general, is politically ineffective needs some more evidence here.

There are also important ways that fiction can theoretically change the world other than driving political activism or awareness. No, climate fiction won’t solve climate change, but might it not have stirred the imagination of the scientists and engineers who invented and refined solar power and batteries — the two technologies with the greatest chance of replacing fossil fuels? Without those green energy technologies, the world would face a bitter choice between runaway climate change and degrowth. But thanks to technologists, we no longer face that tradeoff. If those technologists were inspired by sci-fi, that’s a pretty huge win for the genre.

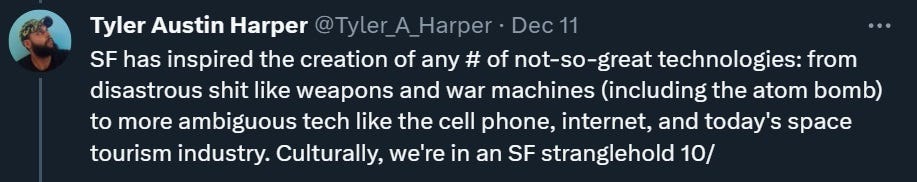

Harper does believe that sci-fi inspires the creation of new technologies. The problem is that he thinks that most of those technologies are bad:

I agree that the internet and cell phones have had an ambiguous overall impact on human welfare. If modern technology does have a Torment Nexus, it’s the mobile-social nexus that keeps us riveted to highly artificial, attenuated parasocial interactions for every waking hour of our day. But these technologies are still very young, and it remains to be seen whether the ways in which we use them will get better or worse over time.

It seems odd to condemn sci-fi for inspiring technologies whose overall goodness we don’t know yet. There are very few technologies — if any — whose impact we can project into the far future at the moment of their inception. So unless you think our species should just refuse to create any new technology at all, you have to accept that each one is going to be a bit of a gamble.

As for weapons of war, those are clearly bad in terms of their direct effects on the people on the receiving end. But it’s possible that more powerful weapons — such as the atomic bomb — serve to deter more deaths than they cause. Deaths from armed conflicts have declined pretty radically since the end of World War 2. Of course we can’t know how long that situation will persist, or whether we’ll one day unleash nuclear holocaust and undo in an instant all the work we’ve done to make the world a more peaceful place. But for now, the trend lines look good.

Finally, we come to AI. Harper declares that AI is “primed to be the most disruptive, damaging, racist, immiserating, and potentially apocalyptic of the 21st century”:

Harper’s general negativity about AI echoes popular sentiment in America. But at this point, all of the harms that Harper predicts are speculative. AI might end up just saving us some time at work, making our cars safer, and bringing up the skill level of below-average workers. At this point we just don’t know. So yes, AI is risky, but the need to manage and limit risk is a far cry from the litany of negative assumptions and extrapolations that often gets flung in the technology’s direction.

Also, it’s interesting that Harper goes after the EA and x-risk people. These are people who worry night and day about the potential catastrophic downsides of AI. They might be a bit weird and even cultish at times, but it’s strange for Harper to bash them while also evincing many of the same worries.

Anyway, I think the main problem with Harper’s argument is simply techno-pessimism. So far, technology’s effects on humanity have been mostly good, lifting us up from the muck of desperate poverty and enabling the creation of a healthier, more peaceful, more humane world. Any serious discussion of the effects of innovation on society must acknowledge that. We might have hit an inflection point where it all goes downhill from here, and future technologies become the Torment Nexuses that we’ve successfully avoided in the past. But it’s very premature to assume we’ve hit that point.

I understand that the 2020s are an exhausted age, in which we’re still reeling from the social ructions of the 2010s. I understand that in such a weary and fearful condition, it’s natural to want to slow the march of technological progress as a proxy for slowing the headlong rush of social progress. And I also understand how easy it is to get negatively polarized against billionaires, and any technologies that billionaires invent, and any literature that billionaires like to read.

But at a time when we’re creating vaccines against cancer and abundant clean energy and any number of other life-improving and productivity-boosting marvels, it’s a little strange to think that technology is ruining the world. The dystopian elements of modern life are mostly just prosaic, old things — political demagogues, sclerotic industries, social divisions, monopoly power, environmental damage, school bullies, crime, opiates, and so on. They’re not inspired by sci-fi or conjured up by billionaires. They’re not as sexy to think about as AI. But if we want to fight dystopia, that’s where we should start.

Good article. One of the most aggravating things for me personally is people who look at art as political propaganda FIRST and everything else second. From the old Moral Majority of the Right to the Social Justice Warriors of the Left, these people are nothing but scolds.

It seems to me the biggest flaw in Harper's argument is that he assumes sci-fi is completely ineffective in inspiring positive change (like fixing climate change) while simultaneously assuming it is 100% effective in inspiring negative change.

I agree there's no concrete evidence that climate fiction has any real positive impact on the world. It might, but there's no way to know. But how does he then go on to claim as accepted fact that the atom bomb was directly inspired by sci-fi? If you believe the latter, then you have to at least seriously consider the former. Anything else is just blatant cherry-picking.