Four interesting econ stories

The banking crisis that wasn't, winning the wars on poverty and cancer, and more!

Housekeeping notes: You may have noticed a couple of changes to Noahpinion! First of all, as promised, I now have my own custom domain name, www.noahpinion.blog. All of the old .substack.com URLs for my old posts will forward to new URLs at the new domain. Second of all, the author picture at the top of each post has been changed! It used to be a portrait of William Butler Yeats; now it’s an actual picture of me.

A lot of things have gone whizzing by lately, so I thought I’d do a roundup of interesting stuff from around the world of economic news and debates. In fact, I’m probably going to start doing a bit more aggregation like this. Up to now, I’ve used this blog almost exclusively for long-form commentary and analysis, and Twitter for quick takes on news items or interesting papers. But to be honest, Twitter is becoming less useful for that sort of thing, as thoughtful people continue to quietly filter away and the platform becomes even more dominated by culture wars and pointless meta-commentary. So I’ll do my part to make the internet just a little more fragmented, as it was meant to be.

I’m also thinking about doing interactive roundups where I solicit interesting stories and research from you, the readers — somewhere between Matt Yglesias’ “mailbag” posts and Tyler Cowen’s “assorted links”. But we’ll talk about that idea more in a bit.

Today, I’m going to cover:

How banking problems are changing from an acute crisis to a longer-term crunch

Why the data tell us that automation really hasn’t taken our jobs (yet)

Why the U.S. is winning the War on Poverty and the War on Cancer

Why generative AI might be the “revenge of the normies” in the labor market

What happened to the banking crisis?

A few weeks ago, in the wake of runs on Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse, a lot of people were expecting a continuing banking crisis. When news came that depositors were fleeing smaller banks for the safety of bigger ones, and fleeing banks in general for the safety of money market funds, the sense that we were in the middle of a rolling, ongoing financial crisis intensified. But so far, the predicted wave of bank failures hasn’t materialized. What’s going on?

A Twitter thread by MIT economist Jonathan Parker has the story, and explains a lot of important things about banking in the process (part 2 of the thread is here, because Twitter now apparently limits threads to 25 tweets). The basic story is twofold:

Banks were never quite as vulnerable as they looked, and

The government has done a lot to backstop the system.

Although social media panics can be the trigger for bank runs, the real reason U.S. banks were in a weak position prior to the SVB collapse was that interest rates had gone up. Banks were holding a lot of bonds, and when interest rates go up, bond prices go down, so the asset side of banks’ balance sheets became much weaker. Interestingly, Parker argues that it was inflation, not the Fed, that was responsible for the rise in long-term rates that weakened the banks. But let’s set that aside for now. The fact is, rates rose and banks’ assets got smaller.

But this didn’t weaken banks as much as people generally think. Because although higher rates decreased banks’ assets, they strengthened banks’ business. As Parker shows, higher rates make banks more profitable, because they can earn higher interest on loans and investments while keeping the rates they pay on checking and savings accounts low:

It turns out that this increase in banks’ future profitability was worth almost exactly as much as the decrease in the value of the assets on their books! Imagine if the value of your 401(k) went down, but your salary went up; that’s basically what happened to the banks.

In other words, rate increases didn’t actually make the banks insolvent. What they did do was make the banks less liquid. In the new higher-rate world, banks have to wait and make money slowly instead of being able to sell bonds quickly, so it’s easier for them to collapse if a bunch of depositors suddenly want their money back all at once. In other words, they became vulnerable to runs, which is why the government stepped in and backstopped bank deposits last month.

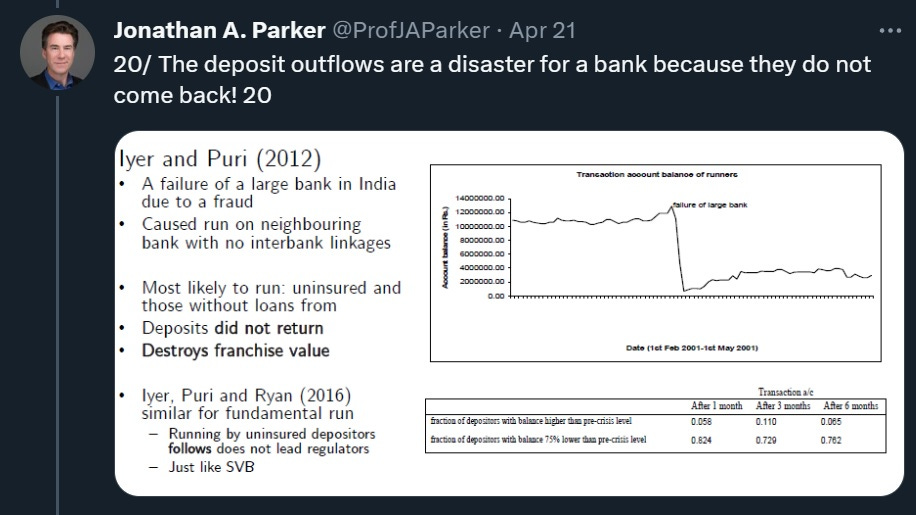

So, crisis averted? Well, not quite. As Parker shows, when deposits leave a bank, they tend never to come back:

So a lot of banks are in long-term trouble; the government will save them from collapse, but they’ve lost a lot of their deposit base for good. The government has turned a crisis into a long-term crunch.

What happens now? Well, for one thing, these banks are going to cut back their lending. As this week’s Odd Lots podcast details, there’s an emerging credit crunch in the U.S. economy, which is exactly what you’d expect from banks having fewer deposits and worrying about their deposits more. Also, there will be a wave of bank mergers, as smaller, weaker banks are absorbed by larger ones.

This is all probably what the U.S. government wants. A credit crunch will slow the economy, dampening inflation. And it’ll do so in an orderly way, without panic.

There is a question, though, of whether bank regulation should change in order to prevent similar episodes in the future. Parker suggests that banks should be prohibited from holding long-dated bonds, which I think is an interesting idea worthy of consideration. After all, banks’ specialty is not asset management; their specialty is making loans. I’m sure there are some complex reasons why banks need to hold some amount of bonds to make their businesses run smoothly or to hedge risks, but overall I think we want to move toward a banking system that spends its time evaluating the credit-worthiness of borrowers instead of just placing bets on interest rates.

Mistaken arguments about AI and jobs

In response to my repeated arguments that AI hasn’t taken our jobs yet and may never do so, several writers have claimed that in fact we do see signs that automation is already making large numbers of humans unemployable. One of these was the historian Peter Turchin, who wrote a thread disputing one of my core arguments.

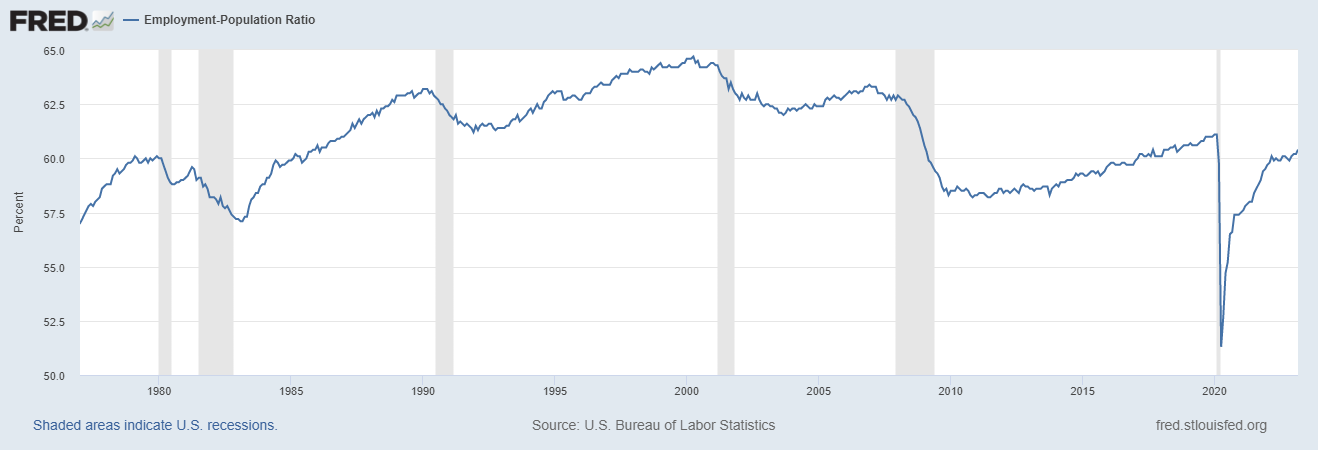

When talking about automation and jobs, I like to point out that the prime-age employment-to-population ratio — that is, the percent of Americans age 25-54 who have jobs — is near its all-time high.

If everyone who wants a job has one, then mass technological unemployment is still a creature of science fiction.

But Turchin disputes this argument on two grounds. First, youth employment rates — which is not included in the “prime-age” category — have plummeted over the years. Second, male labor employment rates have drifted downward, even as female employment rates have risen. Together, Turchin claims, these facts “destroy” this part of my argument.

However, both of Turchin’s points are deeply flawed. First, he notes that the overall employment rate of Americans aged 15-64 — a broader range than the “prime-age” category — has fallen somewhat from its peak:

But Turchin is being tricked by a composition effect. Prime-age people have higher employment rates than old people or young people (that’s why they’re called “prime-age”). A lot of young people are in school, and a lot of old people take early retirement or get disabled.

And the percent of prime-age people in the U.S. has been falling, as the country ages:

This explains why total employment rates have been falling. We can see this by breaking out the subgroups of working-age people — 15-24, 25-54, and 55-64:

As you can see, the green line (prime-age) is well above the other lines, meaning that the decline in the prime-age percentage of population will very mechanically reduce the overall employment rate. Aging, and not automation, is behind the drop that Turchin notes, which is why economists like to look at the prime-age category in the first place.

Also, interestingly, you can see that although young people are working significantly less, old people are working significantly more. In order to tell a story about automation causing people to leave the workforce, you have to tell a story about how machines are replacing young people, encouraging old people to join the workforce, and leaving prime-age people relatively untouched. Maybe it’s possible to tell such a story — it might have to do with the types of jobs that each age group tends to have — but it’s going to be difficult and subtle.

Turchin’s second argument is that women’s entry into the labor force has masked a decline in men’s employment. Mechanically, he’s largely right, though almost all of the effect is before 2000:

Obviously there was a change in gender norms and the gendered division of labor that led women to enter the workforce en masse. But to think that this change affected only women and left men totally untouched — that male employment is purely a function of technology, while women’s employment is purely a function of sexism — makes no sense.

Why wouldn’t the entry of women into the workforce allow a few of their husbands or boyfriends to take some years off of work — to get a degree, to start a business, or even to be a househusband? Note that the number of households with a stay-at-home dad increased by 1.5 percentage points from the late 70s to the 2000s. There are darker explanations as well — the rise of working women might allow sons or husbands or elderly fathers to stay at home and laze about without getting a job, or turn to high-risk inadvisable careers like selling drugs. There are other trends like mass incarceration that have hit men pretty hard (these ratios don’t count the incarcerated in the denominator, but it’s hard for ex-cons to get jobs once they get out). Finally, women might simply have competed a few men out of the workforce entirely.

These explanations make a lot more sense than assuming that men and women’s employment rates move entirely autonomously from one another, and that only men are being replaced by automation.

So no, I don’t think my argument that human beings still have jobs has been “destroyed”.

We’re still winning the wars on poverty and cancer

There’s a common trope that America keeps declaring “war” on various social ills, and keeps losing. With the War on Drugs, this is undoubtedly what happened. But contrary to popular belief, the War on Poverty and the War on Cancer were both quite successful — and progress continues in both.

First, poverty. A lot of conservatives will tell you that despite all the lavish government spending of LBJ’s Great Society, poverty remained stubbornly persistent — a dramatic government failure. In fact, this is a total myth. When economists measure using a fixed standard of living — i.e. what we would have called “poor” in 1960 — they find that the rate of absolute poverty in the U.S. has declined to under 2%, with most of the decline happening in the 60s and early 70s when the Great Society programs were introduced.

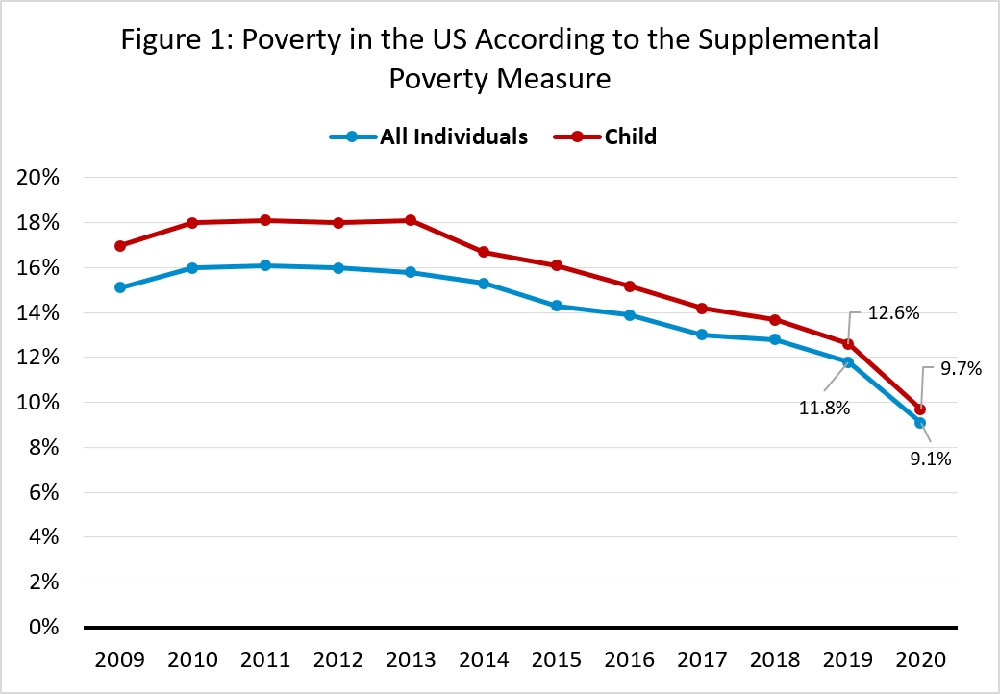

Now, 1960 living standards are a pretty low bar. But even using updated standards — such as the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure — we see that there has been substantial progress. And in fact, much of that progress has come in just the last decade. In 2013, 16% of Americans, and 18% of American Children, were in poverty. By 2019, those numbers had fallen by about a third:

Of course, the pandemic relief programs reduced poverty even more; in 2021 the child poverty rate fell to just 5.2%, though much of that year’s drop will be reversed in 2022 due to the cancellation of Biden’s expanded child tax credit.

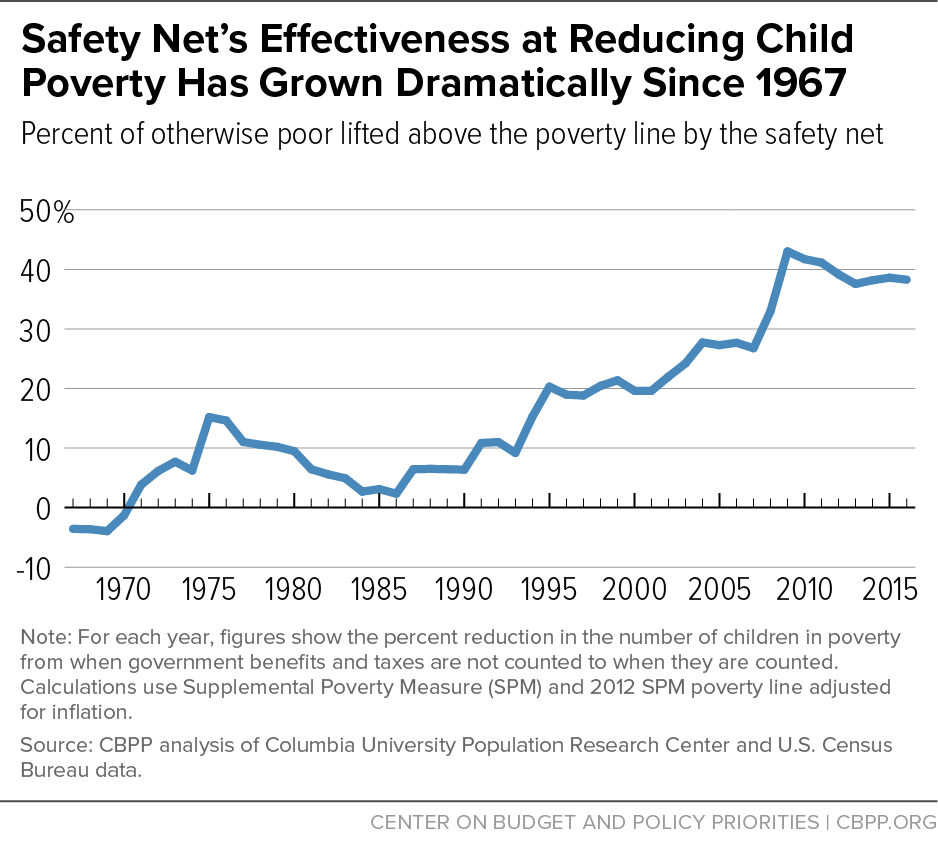

Anyway, the next question is why poverty has been falling. Obviously economic growth is part of the story here, but Isaac Shapiro and Danilo Trisi of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities crunched the numbers and found that the safety net has been keeping a larger and larger share of American kids out of poverty since the late 1980s:

So we’ve actually been winning the war on poverty, although the foe is not yet vanquished.

How about the War on Cancer, declared by Richard Nixon in 1971? It’s very common to see people minimizing the results of our big effort against cancer, or even to say that we’re “losing” the war.

Saloni Dattani has a great thread detailing many of the ways we’ve made progress against cancer over the last two decades. Here’s an especially impressive graph, showing that when you hold age constant, cancer death rates have declined by more than a fifth just since 1999:

Some of that progress has been due to improvements in public health (less smoking), some to better treatments, and some to better testing and early detection. But there’s one additional factor that’s likely to become a much bigger deal in the next few years: vaccines.

MRNA vaccines worked wonders against Covid, and might end up beating malaria, but they’re also turning out to be very effective against cancer; they train the body’s own immune system to attack and destroy cancer cells. The improvements already being reported in trials are pretty impressive:

Moderna Inc. and Merck & Co.’s cancer vaccine helped prevent relapse for melanoma patients, results from a midstage trial showed…About 79% of high-risk melanoma patients who got the personalized vaccine and Merck’s immunotherapy Keytruda were alive and cancer-free at 18 months, compared with about 62% of patients who received immunotherapy alone[.]

In fact, similarly encouraging results are coming out all over the field. By the end of the decade, anti-cancer vaccines could be widespread.

The common myths that the War on Poverty and the War on Cancer were failures were part of a decade-long boom in pessimism about U.S. state capacity. The truth is that the United States is a highly effective country, and we have a good track record of using government initiatives to combat social ills.

AI as the “revenge of the normies”

One of the thorniest debates in the econ world is whether rising inequality since 1980 has been a result of what economists euphemistically call “skill-biased technological change”, or SBTC. This is basically the theory that new technologies — in particular, computers and the internet — give a big boost to smart, well-prepared, well-educated workers, while not giving as much of a boost to those with lower “skills”. In plain terms, this is just the famous Marc Andreessen quote:

The spread of computers and the internet will put jobs in two categories: people who tell computers what to do, and people who are told by computers what to do.

Marc has since repudiated this prediction, but the debate continues. The latest salvo I’ve seen is this 2022 paper by Lazear, Shaw, Hayes and Jedras, who support the SBTC hypothesis:

Wages have spread out across people over time for 15 of 17 countries for 1989-2019, so there is commonality in the pattern of correlation between productivity and, suggesting global rather than institutional factors are at work. Therefore, the most obvious candidate is the often discussed skill-biased nature of technological change, benefiting highly skilled workers.

Across countries, the authors find a strong correlation between productivity changes and wage changes. In the U.S., they find a strong correlation between industries with more educated workers and industries with high productivity and high wages. Unsurprisingly, software is one of the most educated and most productive. They conclude that SBTC is the most likely culprit.

I’m willing to believe that SBTC was one of several factors that made inequality rise in developed countries since 1980. But the real question is whether future technologies will do the same. Lazear et al. predict that AI will exacerbate the skills gap, because its main functions will be A) to generate predictions, which highly skilled people are better able to put to use, and B) to generate ideas, which true “geniuses” will be highly specialized in putting to good use.

But some other research suggests that the opposite might be true — the new generative AI tools might be more effective at boosting the productivity of average people, or even low-skilled people. For example, take this new paper by Brynjolfsson, Li, and Raymond, which measures the effect of an AI tool on the productivity of customer support workers. This is a great industry to measure. It involves lots of talking, and so it’s a natural fit for generative AI. And because it’s easy to measure the output of individual workers — just look at how fast and how satisfactorily customer calls are resolved — it provides a hard measurement of both initial worker skill levels and the effect of AI on individual productivity.

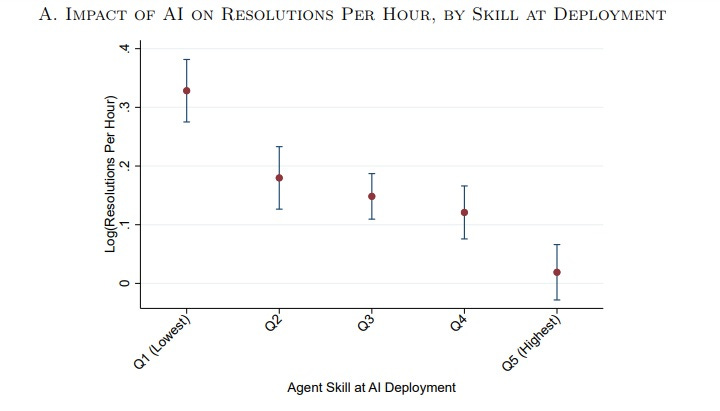

The authors find that their AI “conversational assistant” improves productivity across the board, by about 14%, and has a variety of other positive effects. But the most interesting result, in my opinion, is that the AI tool helps lower-skilled workers more than higher-skilled ones:

AI assistance disproportionately increases the performance less skilled and less experienced workers across all productivity measures we consider…[W]e find that the AI tool helps newer agents move more quickly down the experience curve: treated agents with two months of tenure perform just as well as untreated agents with over six months of tenure. These results contrast, in spirit, with studies that find evidence of skill-biased technical change for earlier waves of computer technology…

[T]he productivity impact of AI assistance is most pronounced for workers in the lowest skill quintile…who see a 35 percent increase in resolutions per hour. In contrast, AI assistance does not lead to any productivity increase for the most skilled workers…[L]ess-skilled agents consistently see the largest gains across our other outcomes…These findings suggest that while lower-skill workers improve from having access to AI recommendations, they may distract the highest-skilled workers, who are already doing their jobs effectively[.]

And here’s their graph:

In other words, for customer support people who can already do their jobs well, AI provides little or no benefit. But for those who are normally pretty bad at their jobs, or are new on the job, the AI tool boosts their skills immensely. This is the exact opposite of skill-biased technological change.

What’s really interesting is that this isn’t the first study to find this pattern. Noy and Zhang (2023) observe the exact same thing for college students doing writing tasks — the AI uplifts the worst performers a lot more than the top ones. And a team at Microsoft Research found that GitHub Copilot improves the coding performance of older developers and less experienced developers more than others.

I think we’re starting to see a pattern emerge here. Generative AI consistently seems to uplift the lowest performers more than the high flyers. And the reason why it does this is pretty simple — if generative AI substitutes for human thought, then it makes sense that it disproportionately empowers those who aren’t as good at handling the cognitive load of their jobs.

In other words, Marc Andreessen’s old quote looks right, in a way…but for a sufficiently smart computer, being told what to do by a computer is actually a plus.

Now, this pattern might not translate from controlled settings and narrowly defined tasks in to the wider working world. It may be that generative AI reduces the premium for narrow sets of skills, but raises the premium for broader skills like mental flexibility, personal initiative, entrepreneurialism, “true genius” (whatever that is), and so on. We’re just at the beginning of this journey into the technological unknown.

But results like these make me think it’s possible that generative AI might be the technological “revenge of the normies”. The master craftspeople of software engineering, financial management, and business communication might find that with just a little help from an AI assistant, a bunch of normal people can do their job. That would be quite an interesting turnaround from the last 40 years. But not an unwelcome one.

Sorry, today I’m the friendly typo-finding guy guy:

“Also, there will be a wave of bank mergers, as smaller, weaker banks are absorbed by smaller ones.“

Absorbed by “larger” ones yes?

Agree on generative AI, at least from my sample of 1. I can never get it to turn out even boilerplate text in less time than it would take me to type something better. But it's comparable to my median student in writing quality, if you don't worry about its capacity for confabulation.