Feeling strangely optimistic about Egypt

It has many of the building blocks for a successful industrialization story.

It’s kind of a tradition for opinion writers to get topic ideas from cab drivers. When I was heading to the airport to go to Ireland and Singapore a few weeks ago, my cabbie, who had recently immigrated from Egypt, asked me to write about his home country.

If Americans think about Egypt’s economy at all (which they typically don’t), they generally regard it as a basket case. And with some justification. It’s a mostly-desert Middle Eastern country with a large and growing population but without much oil, and it runs a large trade deficit. A decade ago it was shaken by a revolution followed by a military coup. The man who spearheaded that coup, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, is still in charge of the country. All of these factors usually make for a pessimistic outlook.

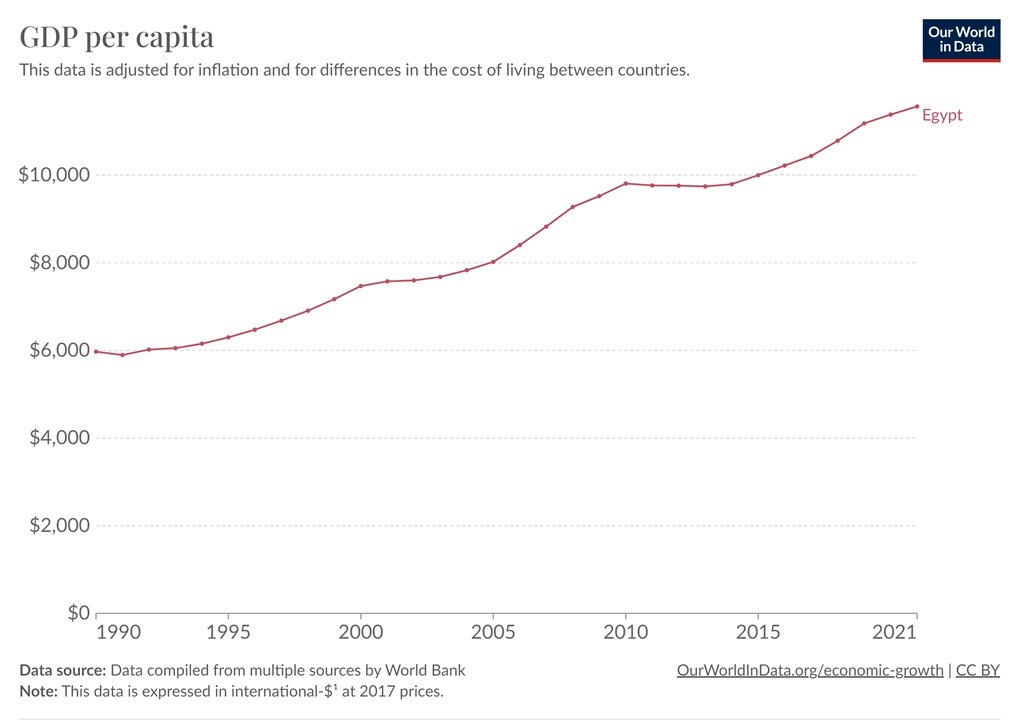

But when I had a chance, I took a closer look at Egypt’s economic situation, and I found some things to be encouraged about. First, there’s the overall growth trajectory. A lot of poor countries have periods where their GDP goes down for a while — they get richer or poorer, depending on resource prices and the domestic political situation. But Egypt’s GDP only plateaued during its period of chaos in 2011-14; in general, it’s been on a slow but steady upward trajectory.

Also, note that although Egypt’s living standards are below the world average, it’s not actually that poor — it’s at about the same level as South Africa or Indonesia. In other words, it’s a solidly middle-income country.

(As a side note, some Americans seem not to have realized it, but much of the developing world looks like this now — instead of a bunch of extremely poor people living in farming villages and growing their own food, it’s a bunch of somewhat-poor people living in apartment buildings in dense big cities and working in local service occupations.)

The encouraging thing about Egypt’s middle-income status is that it isn’t based on exports. Egypt doesn’t sell that much stuff to the outside world at all, actually; its exports are only 15% of GDP, which is quite low compared to most countries. Its biggest export is actually oil, but the total amount of oil it sells outside its borders is quite low — only about as much as Vietnam, which has a similar population. Egypt definitely isn’t a petrostate, by any stretch of the imagination.

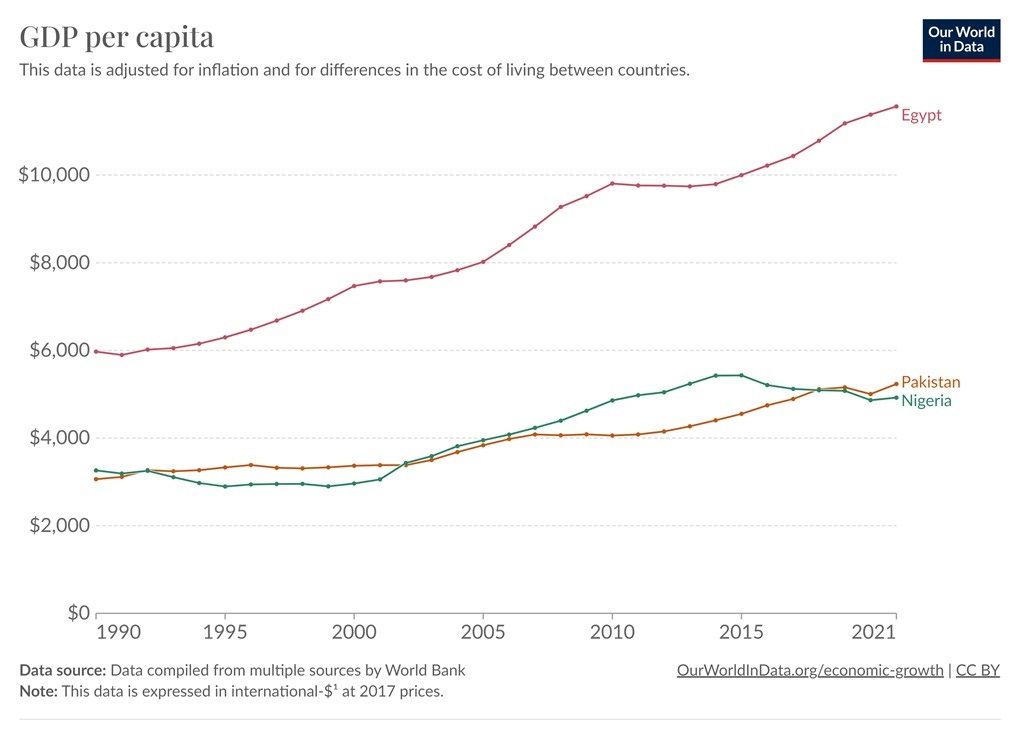

So Egypt’s income must come from the domestic economy — from Egyptians making goods and providing services for each other. The fact that the country has managed to reach middle-income status based almost entirely on its internal economy is an encouraging sign — it means that basic economic mechanisms are functioning with a reasonable amount of efficiency. Compare Egypt to true basket cases like Nigeria or Pakistan:

This means that if Egypt does manage to start exporting more, the growth it gets would come on top of a fairly high existing base. And since Egypt’s domestic economy has proven itself to be relatively efficient, it’s likely that the “multiplier effect” of increased exports would be substantial. So in terms of its position in the global economy, Egypt really has nowhere to go but up.

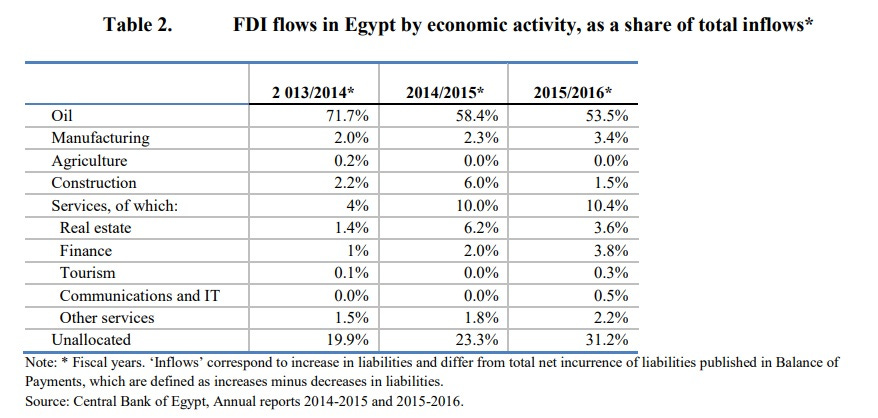

So what are the prospects for Egypt to become an exporter? After looking at various recent industrialization success stories, I’d say that Egypt should probably try luring foreign direct investment in manufacturing. In recent years, most of Egypt’s FDI has gone into the oil and gas sector, with very little going into manufacturing or exportable services:

Egypt does have a few key strengths that make it a potentially good location for export-oriented FDI. First, there’s geography; Egypt is close to Europe, and has a lot of coastline, and most of the population is near the coast. So whatever export goods Egypt makes can be very quickly and cheaply sent to Europe.

A second strength is the potential of the domestic market. Egypt has 113 million people; combine that with a middling level of income and you have a fairly substantial potential market. Companies that build factories and establish branches in Egypt will be more easily able to tap those consumers. And that isn’t even taking into account the markets of the rest of the Middle East and North Africa, for which Egypt could serve as a local production base.

A third advantage is stability. That may seem an odd claim for me to make, just a decade after a revolution and coup. But note that Egypt, unlike many nearby countries that experienced turmoil during the Arab Spring, and despite having somewhat of a youth bulge, did not fall into a civil war. The country has no major racial or ethnic divisions, and only a minor and politically irrelevant religious division (13% of the country is Christian). There are no regional fault lines either; pretty much everyone in the country lives along the Nile river or in the Nile river delta. In other words, there are no natural fault lines along which Egypt could break apart; it’s one of the most homogeneous, unified populations in the world. The major ideological opposition to the government is the Muslim Brotherhood, but so far they show little desire to become armed rebels.

A fourth factor is sunlight. Egypt gets a lot of sun all year round, and has a lot of empty desert land to build solar power. In an era of ultra-cheap solar, Egypt thus has effectively unlimited electricity resources. Cheap, reliable electricity is a key input into manufacturing.

Finally, there’s the fact that Egypt spends a lot of money on infrastructure, especially under el-Sisi. The most spectacular and headline-grabbing investment has been a new administrative capital outside Cairo, complete with skyscrapers, a palace, and even a glass pyramid. (One might say that large, flashy construction projects of questionable economic value are something of an Egyptian tradition.) But in addition to the flashy new capital, el-Sisi has invested in the kind of infrastructure that could make life easier for foreign companies. This includes:

a bunch of new roads

a bunch of new housing

a large nuclear power plant

desert land reclamation

a widening of the Suez Canal

This infrastructure splurge was actually the main positive thing about Egypt that my cab driver mentioned; but while he probably considered its job impact more than its usefulness for attracting FDI, people in el-Sisi’s government are also clearly thinking at least a little bit about attracting investments from abroad. The chosen investments aren’t necessarily exactly aligned with what foreign investors would want, but they will help, and most importantly they demonstrate a willingness to spend and an administrative ability to get things built quickly.

So Egypt has a number of inherent advantages that could be leveraged into an FDI boom. It also has some inherent weaknesses.

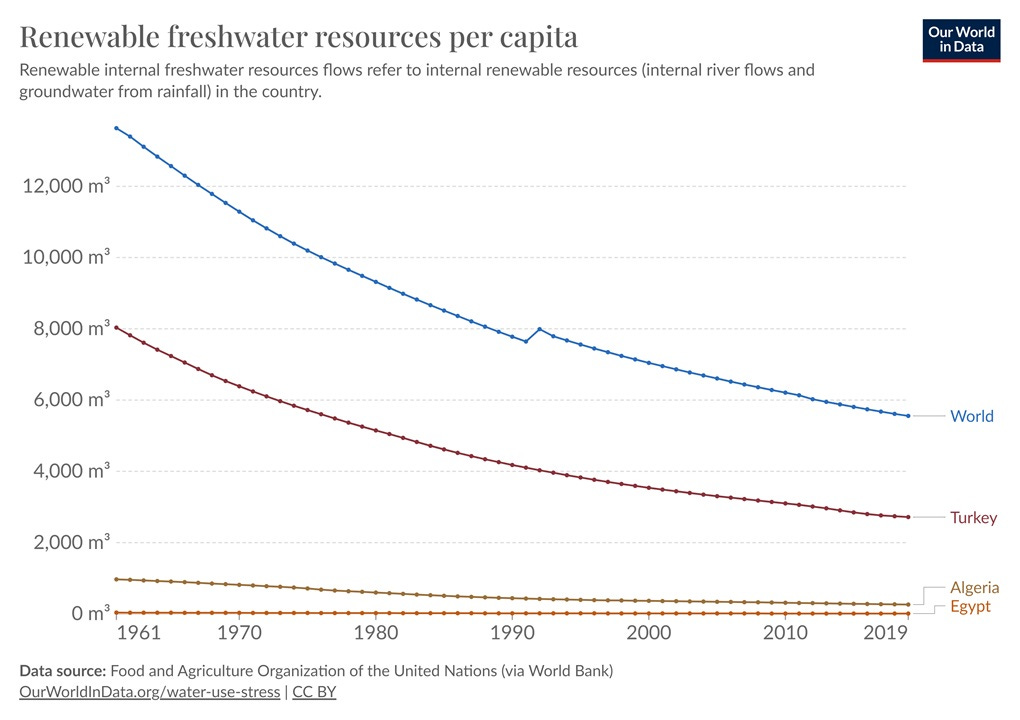

The biggest weakness is water availability. Egypt is practically the driest country on the planet; by the World Bank’s reckoning, Egypt has only 9 cubic meters of renewable internal freshwater resources per capita — the third-lowest value in the world after Bahrain and Kuwait. Here’s a graph, just for illustration:

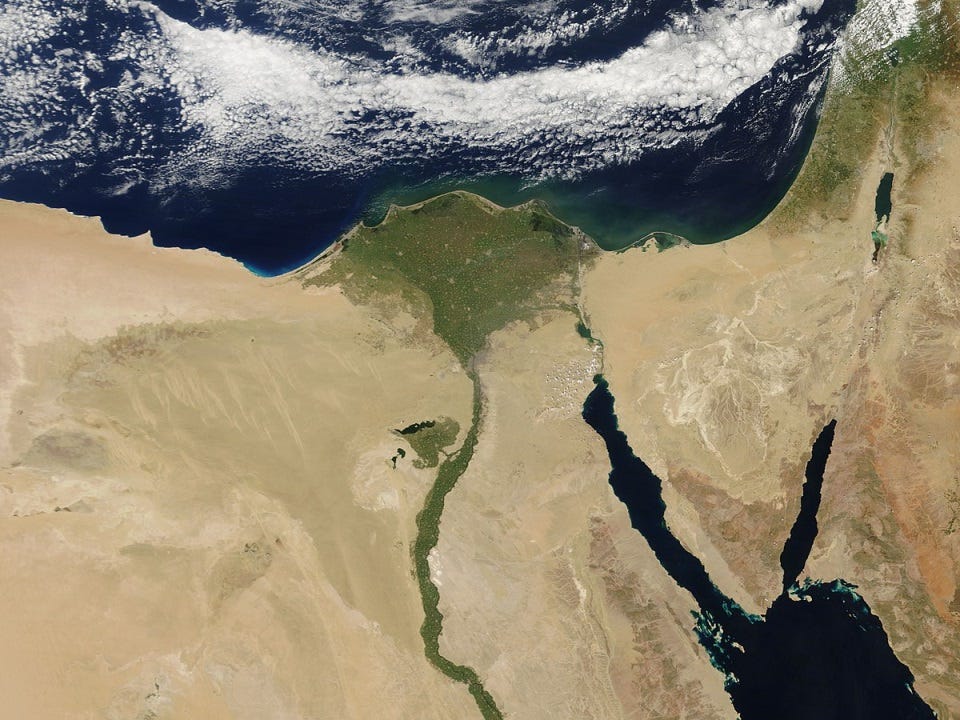

In fact, you can see this from space. Egypt may look like a big country with squarish, blocky borders, but in fact it’s really just a river and a river delta:

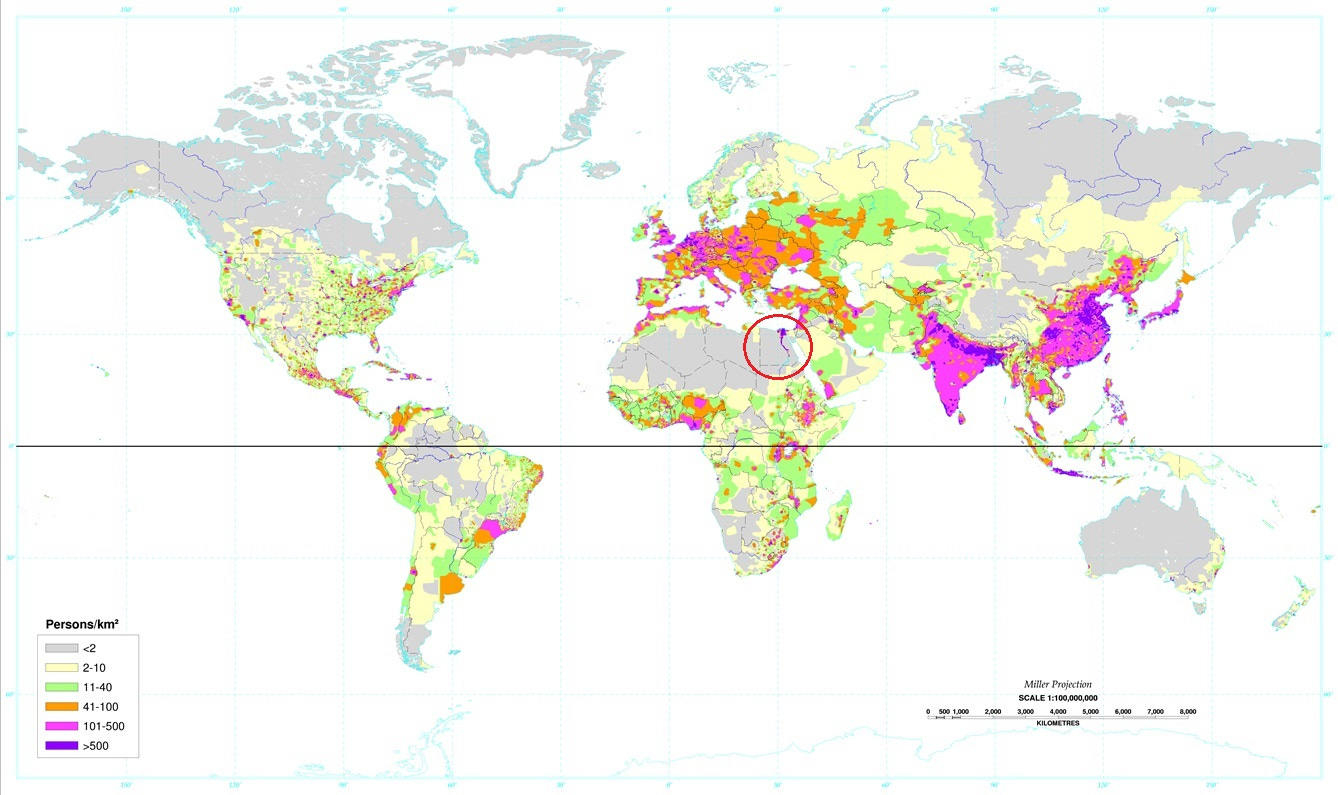

The country is so bone-dry that it’s essentially impossible to live anywhere except right along this thin line of river. There’s no other country on the planet with a population distribution like Egypt’s:

Many kinds of manufacturing can be very water-intensive. For these, the only real hope for Egypt is to use desalination — which is rapidly becoming cheaper — and put the factories on the coast. Cheap solar will help.

But some kinds of manufacturing don’t take a ton of water, as evidenced by the fact that manufacturing (including construction) is around 16% of Egypt’s GDP — a decently high percentage as countries go. So the lack of water resources isn’t necessarily a dealbreaker here.

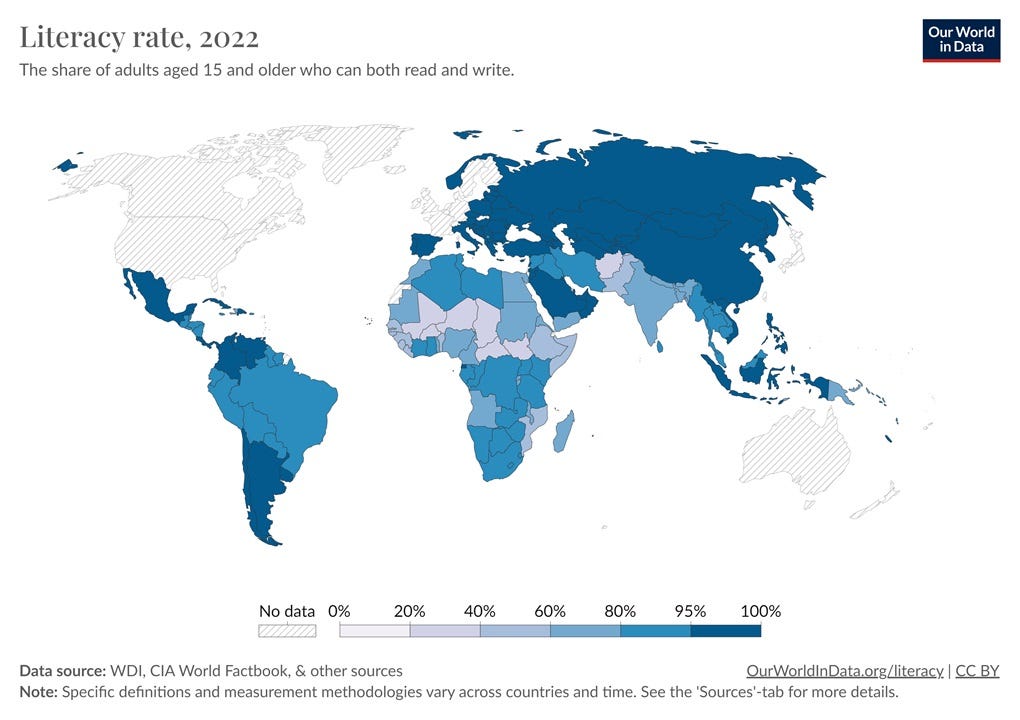

A second hurdle is low education levels. At around 75%, Egypt’s literacy rate is pretty low by modern standards:

Manufacturers need workers who can read and write. This won’t be a problem to start out with, since Egypt has many people who are literate, and since secondary school enrollment rates are actually pretty good. But in the long run, any drive for FDI is going to require more spending on education.

A third problem is corruption, which my cab driver bemoaned at length. Egypt scores poorly on corruption measures, although it’s far from being one of the worst. The key problem is that the military owns or controls many of the country’s businesses. This is similar to Indonesia’s military in the late 20th century, or Iran’s Revolutionary Guard today. Military control of business crowds out the private sector, and is often inefficient because of a lack of competition.

But while solving this problem is a long-term challenge, it doesn’t have to hamper FDI or the growth of manufacturing. Foreign-owned companies will be free of military ownership, and in special economic zones — which Egypt started establishing in 2017 — the foreign companies will be lightly taxed. This will insulate FDI from military competition and extraction. The military is unlikely to mind too much; they will get a big boost simply from the revenue that flows into the rest of the Egyptian economy, benefitting the domestic-facing businesses that they already own.

This is how Indonesia’s military dictator Suharto, whose political career bears some resemblance to el-Sisi’s, was able to engineer an FDI-based manufacturing boom in the 80s and 90s, even as his military kept control of much of the rest of the economy. El-Sisi should consciously try to copy Suharto’s economic strategy.

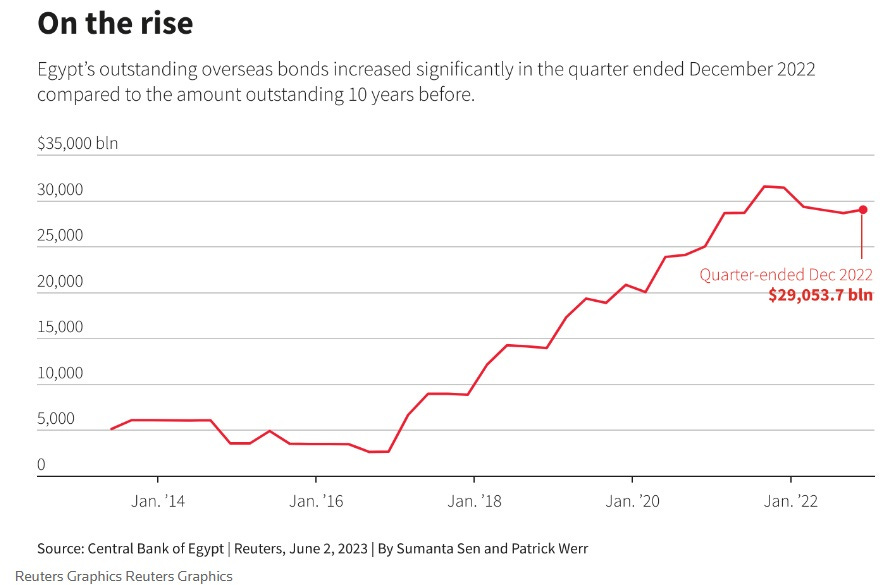

But the biggest danger for Egypt right now isn’t corruption, illiteracy, or lack of water — it’s foreign debt. Egypt has a very low domestic savings rate — only 13% of GDP — so it can’t really fund all the infrastructure spending it’s been doing. Instead, it has largely borrowed the money from abroad. But Egypt can’t borrow in Egyptian pounds; it has to borrow in dollars or euros or some other foreign currency.

That puts Egypt in big danger. Remember how the classic emerging-markets crisis works — a country borrows a bunch of foreign-currency-denominated debt, and then its currency crashes in value, leaving it unable to repay its debt. It then either defaults or prints money and endures hyperinflation, both of which send the economy into a tailspin (though hyperinflation is worse). Egypt is especially in danger of this kind of crisis because it runs a persistent trade deficit. Here’s the story from Reuters:

Few of [the Egyptian government’s] grand projects are generating additional hard currency inflows…global borrowing costs have climbed…Amid a foreign currency crunch, Egypt has drawn down net foreign assets in the banking system by more than $40 billion in two years, partly used to prop up the pound…The hard currency squeeze has raised concerns about Egypt's ability to repay foreign debt. Since April, all three main credit agencies downgraded the outlook for Egyptian debt…

A currency crisis and default would absolutely send Egypt’s growth story into a tailspin, and would lead to massive domestic unrest as regular Egyptians became unable to afford imported wheat. Egypt is very dependent on imported wheat, which is why you always hear about bread riots in Egypt when global food prices rise. If Egypt has a currency crisis, el-Sisi’s rule will clearly be in danger.

The government is aware of the danger. In January, infrastructure projects with substantial foreign funding were paused. But this is just the start; the government will need to scramble to come up with enough foreign currency to repay its external debt over the next year or two.

But even as Egypt works to avoid a debt default, it needs to be working on reorienting its economy for the long term. FDI and exports should be the explicit goal. To this end, the Egyptian government should do the following:

Orient infrastructure spending around the concrete needs of SEZs rather than flashy megaprojects

Increase domestic savings rates, so as not to rely on foreign borrowing

Spend more on education

Improve SEZ policy in various other ways

I know it’s not fashionable to be optimistic about Egypt — and my cab driver certainly wasn’t — but I believe they can do this. They’ve proven themselves to be one of the most stable and peaceful countries in the Middle East, they’ve achieved a middling level of income without significant natural resources, and they’ve shown they’re willing to spend a lot on infrastructure. The pieces aren’t all in place yet for a successful industrialization story, but some of them are, and the government knows that growth is the only thing that will keep its people happy. Egypt has plenty of problems, sure, but it just doesn’t look like a hopeless basket case to me.

Egypt is perhaps the only Arab country which has been a coherent "state" throughout its existence since the days of the Pharaohs. They are not an artificial state such as Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and the like. They have been part of an Empire (ie. The Romans, the Mamluks, the Ottomans), but they were always distinctive and special. In fact, even during the days of Empire, Egypt enjoyed considerable autonomy and Mehmed Ali was one of the very first Muslim modernizers. Egypt has the potential to become a major player in the region. The West should support their journey.

Wikipedia also has this which seems amazing for the Middle East?

"El-Sisi has called for the reform and modernisation of Islam;[96] to that end, he has taken measures within Egypt such as regulating mosque sermons and changing school textbooks (including the removal of some content on Saladin and Uqba ibn Nafi inciting or glorifying hatred and violence).[97][98] He has also called for an end to the Islamic verbal divorce; however, this was rejected by a council of scholars from Al-Azhar University.[99]"

Sisi was apparently educated at West Point. Interesting.