Economic losses for our allies are not wins for the U.S.

Stop comparing ourselves to countries who are on our side.

Here is what I consider to be an absolutely crazy headline from Axios:

Don’t blame Neil Irwin for this one; he is a good writer, and his article soberly assesses the factors hurting Europe. I’m sure that like almost all writers at major publications, he doesn’t get to choose the headlines for his articles. But it’s infuriating and a bit astounding that someone at Axios decided to label a comparison of the U.S. with its allies a “world economic war”.

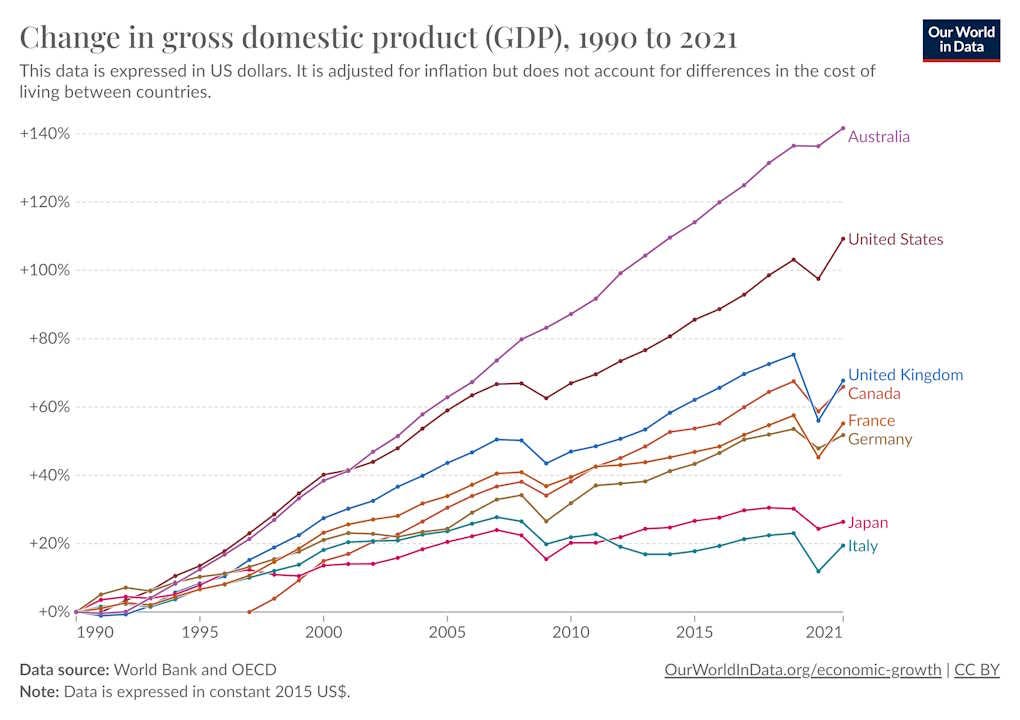

In fact, this is something I encounter a lot — people trumpeting the U.S. economy’s performance relative to Japan, Europe, Canada, etc. I’m not disputing that this trend is real; it certainly is. Since 1990, the U.S. has strongly outpaced most other rich nations in terms of economic size:

This is what has allowed the U.S. to maintain a fairly constant share of global GDP over the last few decades, even as China and parts of Southeast Asia and East Europe caught up.

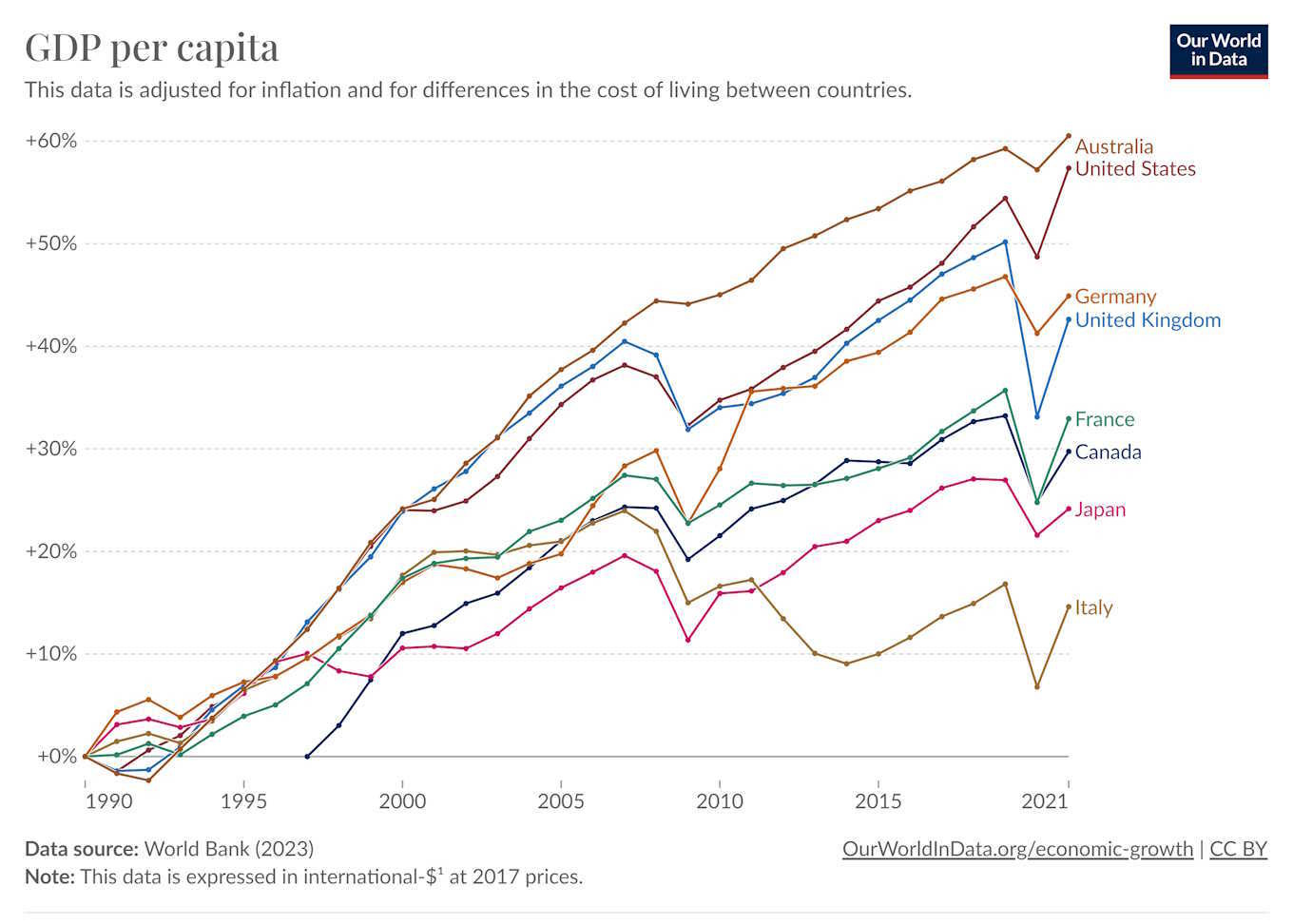

Partly this is because U.S. living standards have risen more quickly:

And partly it was because the U.S.’ population grew faster than most of the others, thanks to high immigration rates and more robust fertility.

So it’s not crazy to say that the U.S. is outpacing our democratic developed allies; it’s simply wrong to think that this represents something to celebrate.

Some portion of the divergence is due to benign factors. Workers in many European countries work fewer hours than their American counterparts, often as a matter of policy; this reduces per capita GDP, but really it just represents a different choice between labor and leisure. Meanwhile, some of the comparisons you see out there are at market exchange rates; some part of what looks like a U.S. advantage is really just the dollar becoming less competitive.

Another portion of the difference might be due to advantages in the U.S.’ economic model. This is very hard to determine, because there are so many confounding factors. But there are some cases where Europe has clearly hurt its economy through regulation. For example, GDPR, whatever its benefits for privacy, has imposed real economic costs on companies. This is from a literature review by Johnson (2022):

This paper reviews the economic literature on the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)…The economic literature on the GDPR to date has largely—though not universally—documented harms to firms. These harms include firm performance, innovation, competition, the web, and marketing.

Overregulation of the software industry is probably a reason why Europe doesn’t have equivalents of Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Amazon, despite being richly endowed with talented software engineers and good universities. Failing in key high-value-added industries will certainly reduce productivity.

But these, too, represent Europe making different choices than America. The U.S. can taunt Europe with the bigger houses and better appliances that our software industry lets us afford, and they can taunt us with the fact that they’re more protected from the modern menace of browser cookies.

On the other hand, there are plenty of cases where other rich countries have clearly just stumbled in some profound way. The most severe example is Italy. Back in 1990, Americans and Italians had pretty similar living standards. Just three decades later, the U.S. was half again as high:

Part of this obviously stems from the two countries’ differing trajectories after the financial crisis of 2008; the U.S.’ bolder fiscal stimulus and more aggressive removal of bad debts from the balance sheets of private banks allowed it to emerge from the aftermath of that crisis more quickly than most of Europe. But Italy was falling behind well before 2008. Severe aging and lack of investment in education are other problems.

The divergence between the U.S. and Japan is almost as stark:

I’ve written extensively on why this is happening, so I won’t belabor you with a lengthy reiteration. Basically, Japan has 1) severe aging, and 2) low productivity that stems from a broken corporate culture that promotes people based on seniority instead of merit and forces employees to do lots of unproductive busy-work.

There are also probably other factors, like export weakness and exposure to competition from China. But in general, none of these things have upsides. Japan is becoming a shabbier country; the cities still glitter, but if you go to people’s homes you see that these people are a lot poorer than Americans, even though they work longer hours.

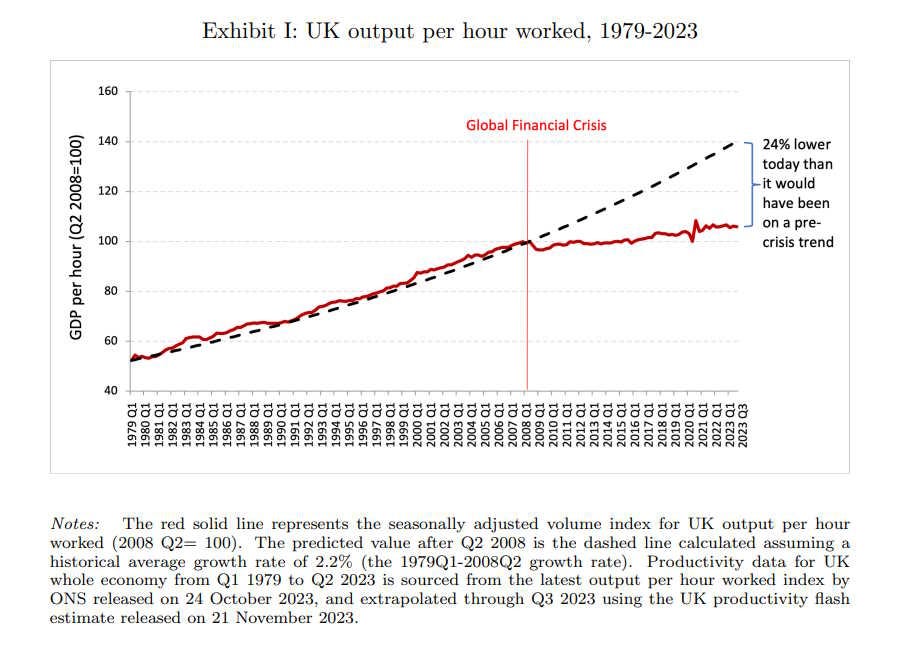

The UK and Germany are also at risk of falling significantly behind. The UK’s output per hour worked has basically not grown at all since 2008:

Economists largely agree that a big reason for this is the UK’s chronic lack of business investment. This has multiple causes — a finance-heavy industrial policy that meant Britain was hit harder by the financial crisis than other countries, a NIMBY system that makes it very hard to build housing or factories, low R&D spending compared to other countries, and of course Brexit.

As for Germany, it was doing great during the 2010s, on the back of strong export performance — some of which came from Chinese demand, and some of which came from structural trade surpluses with hapless South European countries who were unable to depreciate their currencies because they were part of the euro.

But in the past couple of years, the German industrial machine has hit a brick wall. Germany’s economy shrank by 0.3% in 2023, and you can read tons of stories about how industrial companies are thinking of moving out of the country. Everyone agrees that the cutoff of cheap Russian gas — which it was pretty foolish of Germany to let itself depend on in the first place — is a big part of this. The country’s even more foolish choice to get rid of its nuclear plants has only exacerbated the energy crunch. But many observers claim that during the good years of the 2010s, Germany allowed itself to become rigid and over-regulated.

Absolutely none of this is good news for the U.S. A poorer, weaker Germany, UK, and Italy mean that Europe will have to rely more on an already overstretched America for defense against the Russian threat. They will buy fewer American-made products, meaning less export revenue for U.S. businesses. And they’ll be far less likely to assist the U.S. in deterring Chinese aggression in Asia. Meanwhile, Japan is the U.S. staunchest friend in the Pacific, and our main ally in any prospective war over Taiwan. A weaker Japan means a weaker America.

And yet somehow, many Americans don’t seem to get the message. We sneer at the “europoors”, as if people in free, democratic countries allied with the U.S. getting poorer somehow makes us better off. Meanwhile, Trump hit both Europe and Japan with tariffs; even though the Biden administration has rescinded them, the scars remain. And now Americans on both sides of the political aisle are up in arms over the acquisition of U.S. steel by a Japanese company, even though Japan is a friendly country, and even though Japanese management is probably less likely to lay off U.S. steelworkers.

It’s almost as if some Americans are dealing with the psychic impact of our country’s institutional dysfunction, and our decline relative to China, by punching down on whoever is available to be punched down on — namely, our allies who are struggling even more than we are.

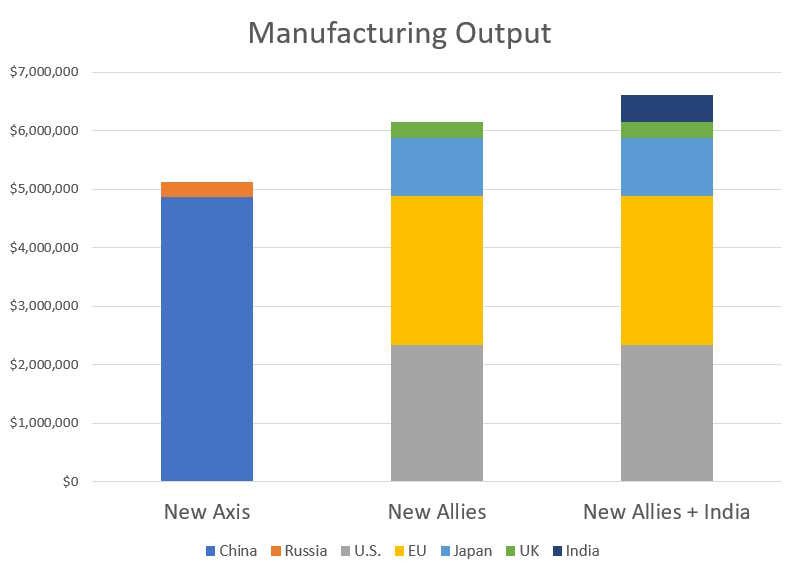

This attitude needs to stop. I urge everyone in the U.S. to remember this chart:

China’s manufacturing prowess is so vast that only by combining their industrial might can the developed democracies hope to match it. This will not happen if we continue to view allies’ companies and allies’ exports with suspicion and antagonism. We need to stop thinking of Germany, the UK, Japan, etc. as our old rivals, and start thinking of them as our indispensable partners. Their strength is our strength, and their weakness is our weakness.

This is something we realized in the aftermath of World War 2 and the early days of the first Cold War, when we did the Marshall Plan and opened our markets to European and Japanese goods. We need to remember that spirit right now.

Agree..... it is better to be helpful vs boastful. Two further points:

1) Culture: One of the key reasons for the difference between Europe and US growth rates is cultural around the topic of risk. The US system rewards risk and allows for creative destruction (at least away from government influenced markets). The European system/culture is more protective. It goes beyond regulation...it is deeply cultural.

2) China Manufacturing: I wonder about the accuracy of the Chinese manufacturing data. If you do final assembly, are you really manufacturing the good.. this is the case for cell phones.

Let me steelman for a second - I think when people bring up comparative growth rates, they are not "sneering at the Europoors"; they are presenting real-world evidence about the outcomes of different economic choices.