Why the U.S. steel industry is dying

It's not because of foreign competition.

This week the U.S. government experienced a spasm of anxiety over America’s declining industrial might. Only for the first time in a long while, the foreign country they worried might supplant us wasn’t China, but…Japan. Nippon Steel, a Japanese steel company, has acquired U.S. Steel. But some politicians — including Pennsylvania Senator John Fetterman — have been lobbying hard to block the sale on national security grounds. The United Steelworkers also oppose the deal.

Why are they worried? Fear of layoffs is part of it, of course. But anyone who knows Japanese companies knows that they’re much more shy about laying off workers than U.S. companies are. Certainly, U.S. Steel itself has had no compunctions about laying off large numbers of steelworkers — 1000 workers at Granite City, IL this year, 1500 workers in Detroit in 2019, 1100 workers in Alabama in 2015, and so on. The U.S. steel industry in general has lost about a third of its workforce since the turn of the century; Japanese management is unlikely to be worse.

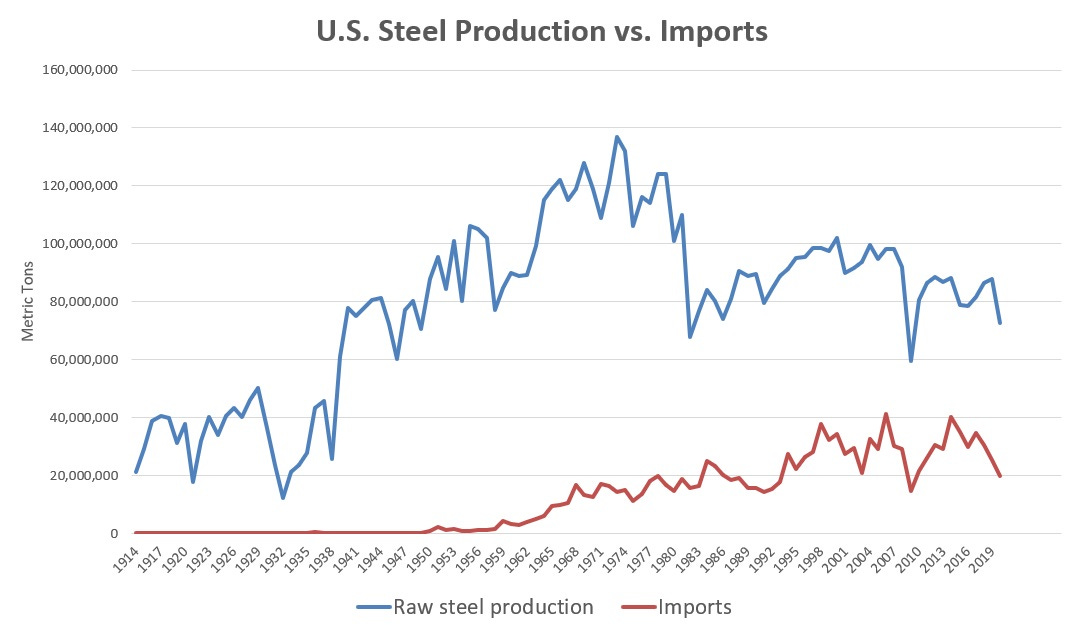

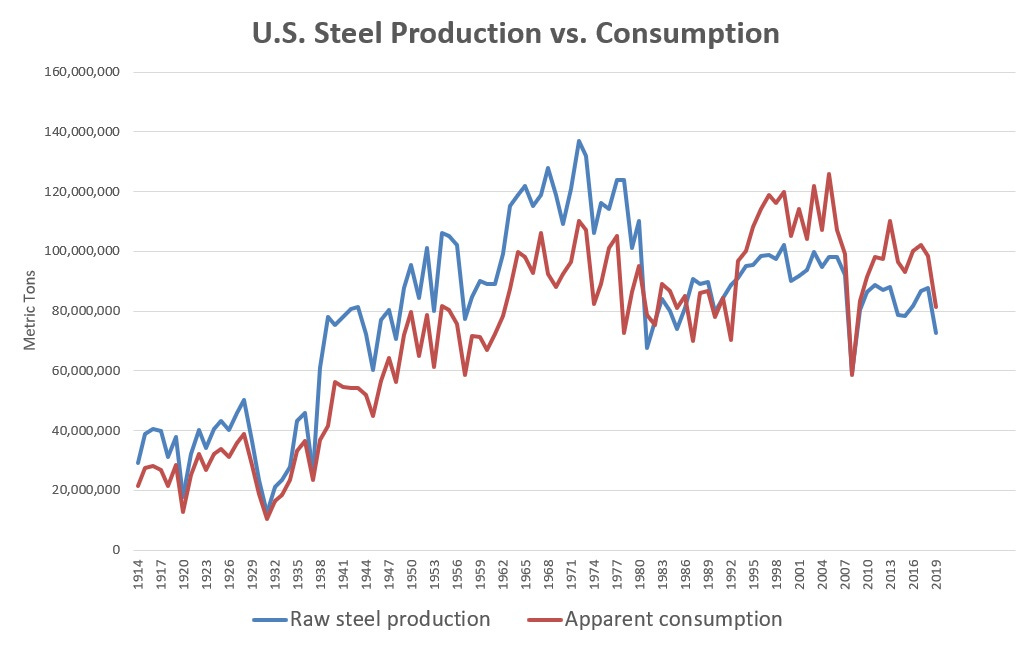

The real fear about the U.S. steel deal, though, is about America’s industrial decline. The stories about U.S. steel all mention that it’s “iconic” — it was started by Andrew Carnegie! — and its merger with a foreign company just seems to underscore how far the once-mighty American steelmaking industry has fallen. Total steel production is lower than it was half a century ago:

In terms of tonnage, it’s lower than in the 1950s. And as a fraction of overall industrial production, steel is a faint shadow of what it once was:

In corporate terms, U.S. Steel itself is a paltry thing — even at the huge premium that Nippon Steel paid for it, its purchase price of $14.9 billion was still only about three quarters of what Adobe wanted to pay for the online design tool Figma.

Blocking the acquisition of U.S. Steel will do precisely nothing to reverse or even slow the U.S. steel industry’s seemingly terminal decline.

So why did this happen? Why did the U.S. go from a steelmaking powerhouse to an also-ran? As usual, there are a bunch of competing explanations — import competition, bad management choices by steel companies, and unions raising wages to uncompetitive levels. But while these were factors, the biggest reason the U.S. steel industry went into terminal decline was that we stopped building things that used lots of steel.

The usual suspects: imports, bad management, and unions

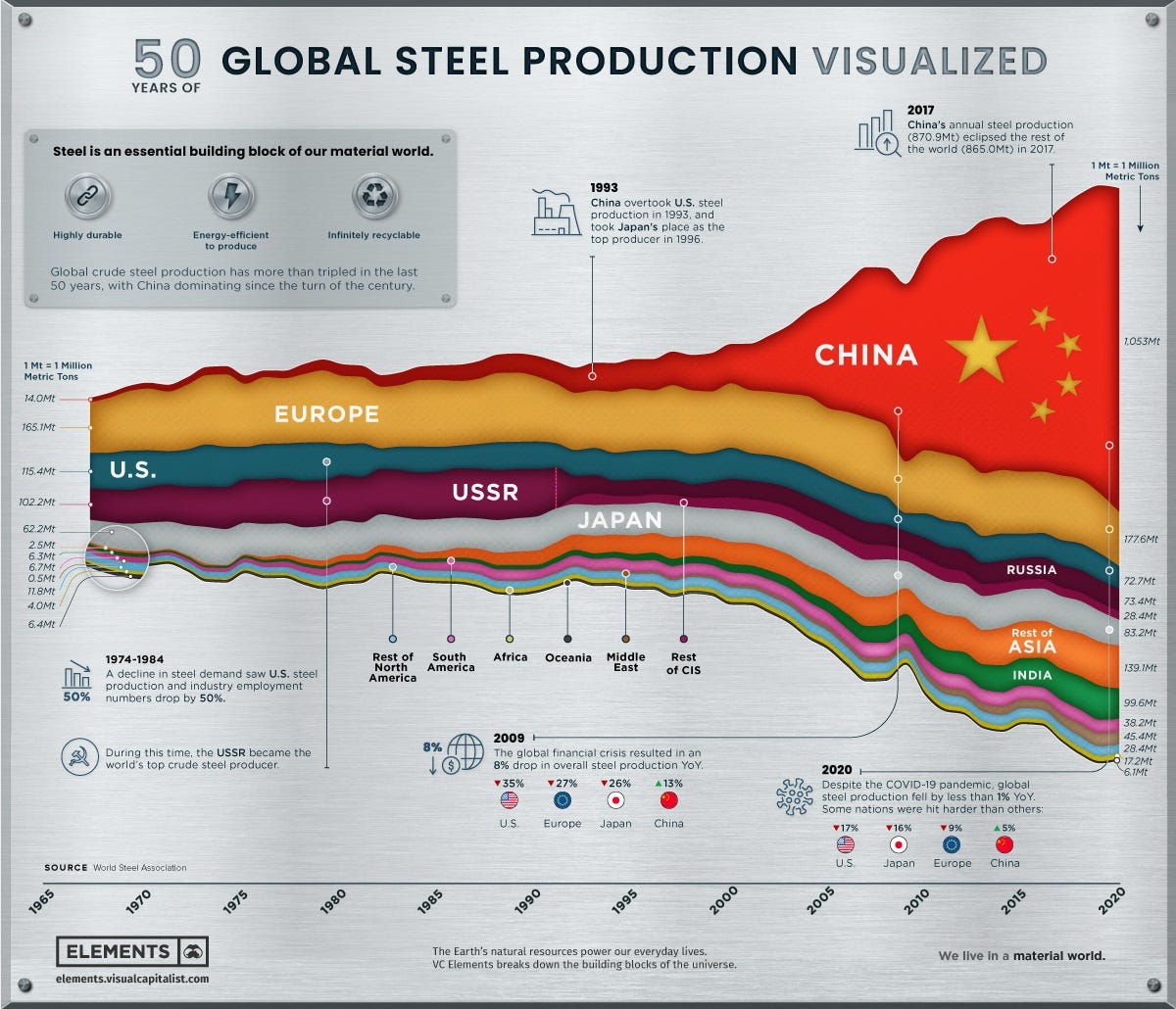

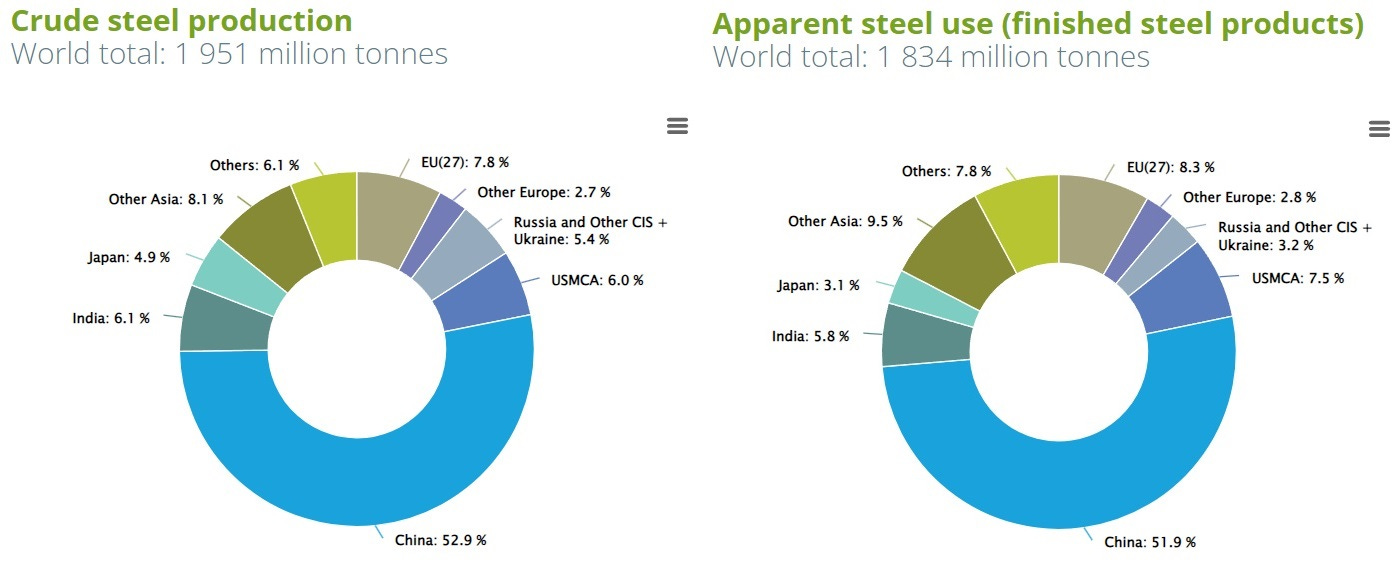

To understand what’s happening in the U.S. steel industry, it helps to zoom out and look at what’s happening elsewhere in the world. Steel production in most places has seen only modest changes since the 1970s, with one huge exception: China.

China now makes a majority of the world’s steel, fulfilling Mao Zedong’s old dream. It’s tempting to look at that graph and conclude that China has become the U.S.’ factory, and that the U.S.’ own steel industry has been slaughtered by a wave of cheap Chinese imports.

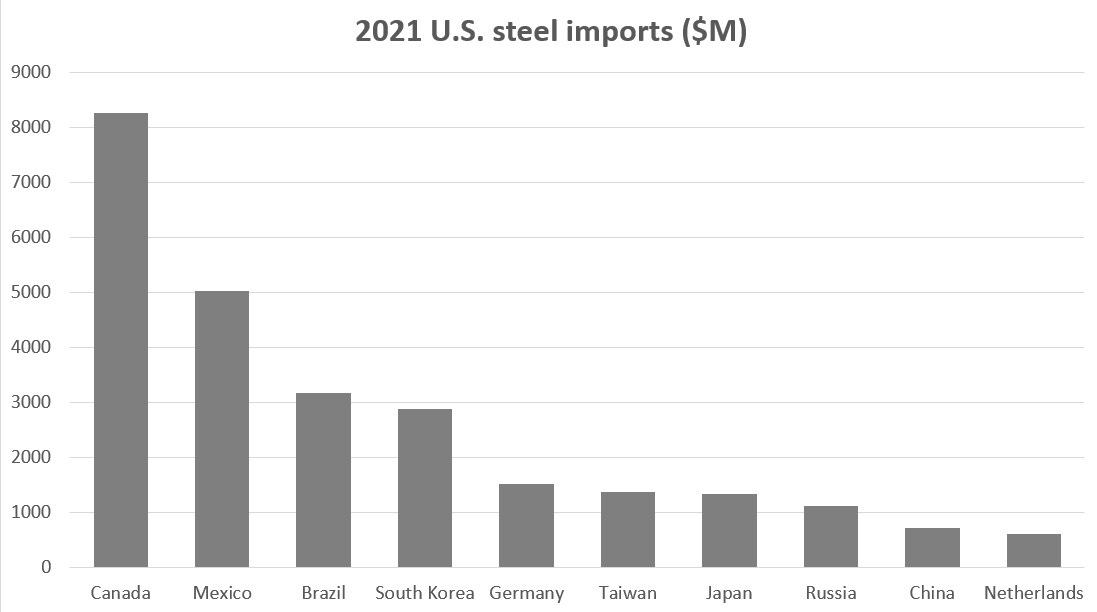

In fact, that’s just false. First of all, the big decrease in U.S. steel production happened in the 1970s, when Chinese production was practically nonexistent. But also, the U.S. imports very little steel from China — America’s biggest foreign suppliers are Canada and Mexico, while China is just a footnote.

There are other reasons to doubt the “import competition” story as the main factor here. U.S. steel production mostly fell during the 1970s, at a time when imports weren’t really rising much at all. Imports themselves rose first in the 1960s and then in the 1990s, at times when U.S. production was flat or rising; other than those times, imports have been basically flat. In fact, in terms of raw tonnage, steel imports were barely larger in 2019 than in 1968:

This just doesn’t look like a chart of imports replacing domestic production.

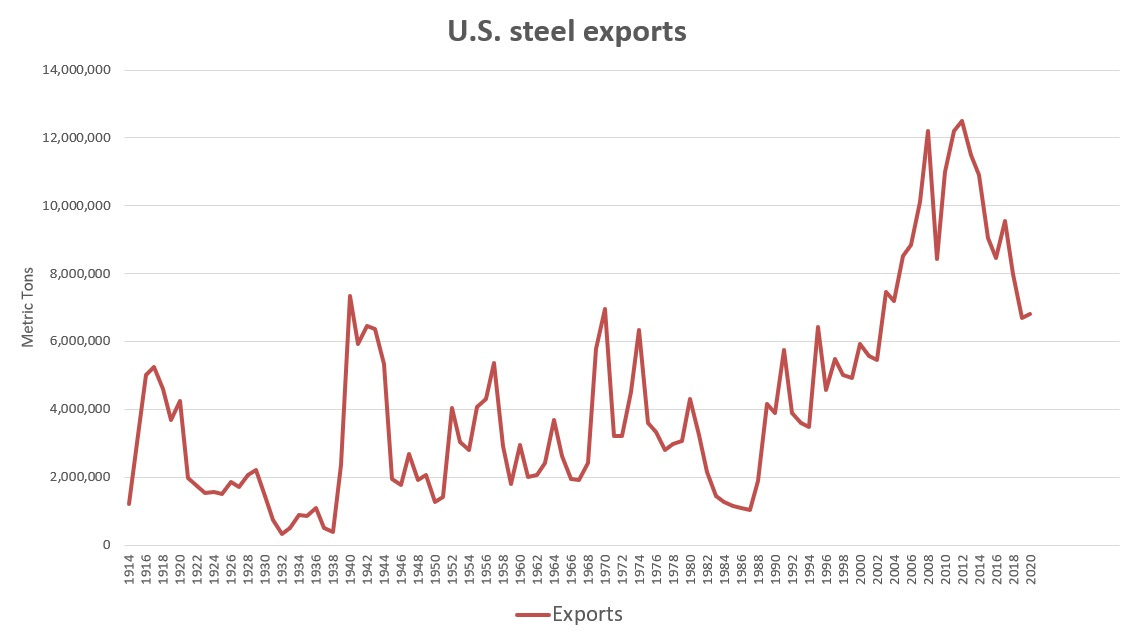

Of course exports matter too. If exports drop, it’s a sign of falling competitiveness. But America’s steel exports were at record highs from the late 2000s through the 2010s:

Almost all of this was exported to Canada and Mexico.

Finally, note that the expansion of imports was pretty modest. In 1974, when U.S. steel production peaked, imports were 13.7% of total U.S. steel consumption. In 2019 they were only up to 24.6%, and in 2022 they were about 24%. That’s an increase, but not a huge increase.

So really, there’s just nothing in the data here that suggests import competition, or loss of competitiveness, as a major driver of falling U.S. steel production.

This also casts doubt on the other two main explanations for the decline of American steel: bad management and unions. We would expect either of those factors to hurt American competitiveness relative to other countries. But since U.S. steel exports soared in the late 2000s and 2010s, and imports barely rose, there’s just not much reason to think the U.S. industry is uncompetitive in the first place. So hunting around for explanations that involve a lack of competitiveness doesn’t make a ton of sense.

But in any case, we can take a look at the “management” and “labor” stories too.

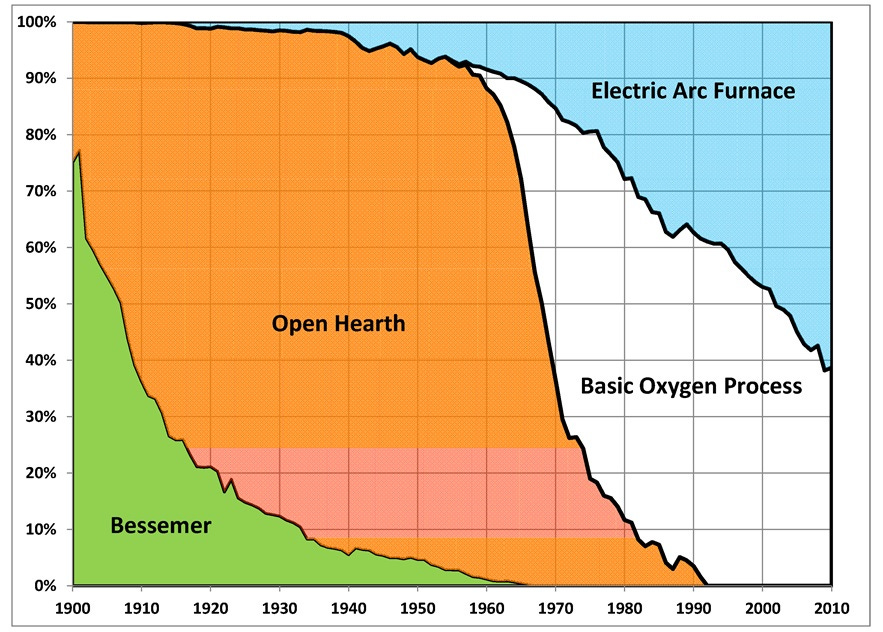

The “management” story says that U.S. steelmakers were slow to adopt new technologies. Basically, there are two ways to make steel products. You can either make them directly from iron ore in an integrated mill, or you can make them by melting down existing pieces of steel or iron in a mini-mill. Integrated mills have used a number of technologies over the years, but the big shift in modern times was from open-hearth furnaces — the rivers of molten metal that you see in pictures of old steel mills — to the basic-oxygen process. The basic-oxygen process (thus named because of the use of alkaline chemicals, not because the process is simple) can make steel about 15 times faster than an open-hearth furnace. Mini-mills use something called an electric arc furnace, which is even more productive — partly because it does fewer chemical steps, but partly because you can turn it on and off very quickly.

A big part of making the steel industry more productive over the last half century or so involved either A) switching from the old open-hearth furnaces to the newer basic-oxygen process, or B) switching your business model entirely to making steel from scraps in mini-mills using electric arc furnaces. In fact, the U.S. has made both of these switches — the first one very rapidly in the 1970s, the second one more slowly since then.

Now, you may notice that the switch from open-hearth to basic-oxygen coincides pretty perfectly with the collapse of U.S. steel production in the 1970s and early 1980s. That suggests that U.S. steel producers didn’t actually fully switch to the new technology — instead what they did was to close down a lot of their old open-hearth plants, but to only partially replace them with basic-oxygen plants.

So this could indeed be a story about bad corporate management — instead of investing heavily in newer, better methods of steelmaking, U.S. producers simply let their businesses shrink in response to a shift in technology. A 1999 study by Lieberman and Johnson, comparing the U.S. and Japanese steel industries, found that Japanese steelmakers out-produced their American counterparts by investing heavily in new technologies:

U.S. firms were often the early adopters of technologies that currently dominate the production of steel in the world, but U.S. companies failed to thoroughly implement these technologies as quickly as the Japanese and other foreign competitors. Faced with growing pressure from imports and unionized labor…U.S. integrated producers responded by cutting investment in new plants and equipment…Meanwhile, Japanese producers embraced and implemented the new technologies for steel production in facilities of ever-larger scale.

The basic-oxygen process was a big part of this new technology adoption in the 60s and 70s, as Kobayashi (2023) shows.

So Japanese companies, which were in high-growth mode due to the booming Japanese economy, were eager to invest, while American producers shied away from the fixed costs associated with new technologies — a case of management obsessed with short-term cost-cutting at the expense of long-term competitiveness. This story of lagging technology adoption is also consistent with the deep but temporary plunge in U.S. steel exports in the 1970s and early 1980s.

It’s also consistent with the story of unionized labor driving U.S. costs too high in the 70s. A 1987 IMF analysis showed that in 1983, Japan had much lower labor costs than the U.S.

It was also in the 80s, however, that the situation started to turn around. That’s when the U.S. really started to ramp up the use of mini-mills, using electric arc furnaces to turn scrap into new steel parts. Lieberman and Johnson show that Nucor, a U.S. steel producer that focuses entirely on mini-mills, improved its total factor productivity to exceed that of the Japanese producers. A Brookings report shows that U.S. steelmaking TFP outpaced Japan in the 90s and 00s.

Collard-Wexler and De Loecker (2015) have an excellent paper in which they show how the adoption of mini-mill technology led to dramatic gains in total factor productivity for the U.S. steel industry:

The increase in productivity can be directly linked to the introduction of a new production technology, the steel minimill. The minimill displaced the older technology, called vertically integrated production, and this reallocation of output was responsible for about a third of the increase in the industry’s total factor productivity. In addition, minimills’ productivity steadily increased. We can directly attribute almost half of the aggregate productivity growth in steel to the entry of this new technology.

Not only did mini-mills improve productivity directly, they also increased competition in the overall steel industry, forcing uncompetitive old steel companies out of business and forcing the best integrated producers to up their game.

Thanks to mini-mills, it’s Nucor, not U.S. steel, that is now the U.S.’ largest steelmaker. (U.S. Steel is investing in mini-mills too, but it’s racing to catch up). Nucor’s market cap is $43.4 billion — about three times that of U.S. Steel, even after the huge price premium from the acquisition. But if Nippon Steel were trying to buy Nucor, I doubt that John Fetterman and the Pennsylvania Dems would be so up in arms!

Anyway, the shift to mini-mills involved an even bigger shift in management than the switch to basic-oxygen technology — instead of simply investing in a new process, it entailed finding whole new supply chains and developing a whole new business model for selling steel. So the “bad management” story of the U.S. steel industry seems like it was basically over by the 90s.

The “high wages” story was pretty much over too. A report by the European Commission found that by 2008-10, U.S. unit labor costs — the amount of labor hours required to produce a single ton of steel product — were very comparable to those in Japan, Europe, and elsewhere. (I am not going to screenshot this report because its charts are really badly formatted, but it’s free to read if you click that link.)

In fact, from 1990 to 2005, U.S. unit labor costs in the steel industry fell pretty dramatically:

So basically, the story of bad management, slow technology adoption, and high wages in the steel industry leading to a loss of U.S. competitiveness was real, but it was over by the late 80s or 90s.

But despite all of these improvements, U.S. total steel production didn’t increase in the 2000s. But exports did increase! Because the U.S. was using less and less and steel domestically, the improvement in competitiveness and productivity manifested as a rise in exports rather than a rise in total production.

Which brings me to the real reason the U.S. steel industry is dying: The U.S. stopped consuming steel.

The U.S. stopped making steel because we stopped using steel

Sometimes I fail to find the answer to one of these big mysterious question, like why groceries are still so expensive. But this time, I think the answer is fairly obvious. If you draw a chart of U.S. steel production and consumption, it’s apparent that they’re very tightly correlated, and always have been:

In other words, the U.S. has switched from a modest steelmaking surplus to a modest deficit, but even if we had retained the surplus we had in the 1960s, our total steel production would likely be flat.

In fact, this is true for pretty much every country. Here are some graphs of where steel is produced and where it’s consumed. The graphs look pretty much identical, because steel is usually produced where it’s consumed.

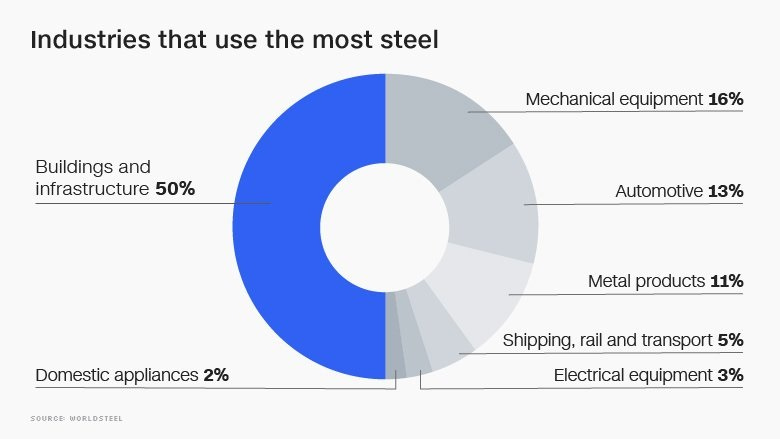

And who uses steel? Remember that steel products are mostly intermediate goods — almost all of it gets bought by other industries as a production input, rather than by consumers. The biggest consumer of steel, by far, is the construction industry — i.e., buildings, highways, railroads, and other infrastructure. Auto manufacturing and mechanical equipment are the other two big ones.

You can look at various different sources for different countries and time periods; they’ll all show slightly different proportions, but they all tell the same story. Buildings, infrastructure, cars, and machinery are the things that matter for steel demand.

The main reason China has been producing such an insanely huge amount of steel is that it’s been on a massive building boom — creating vast forests of apartments and offices, huge networks of highways and trains, and oceans of massive factories. It has also been on a heavy manufacturing spree, producing enormous amounts of vehicles and machinery. You’ve probably heard that in the 2010s, China used as much cement every couple of years as the U.S. did in the entire 20th century. Steel was simply a similar situation.

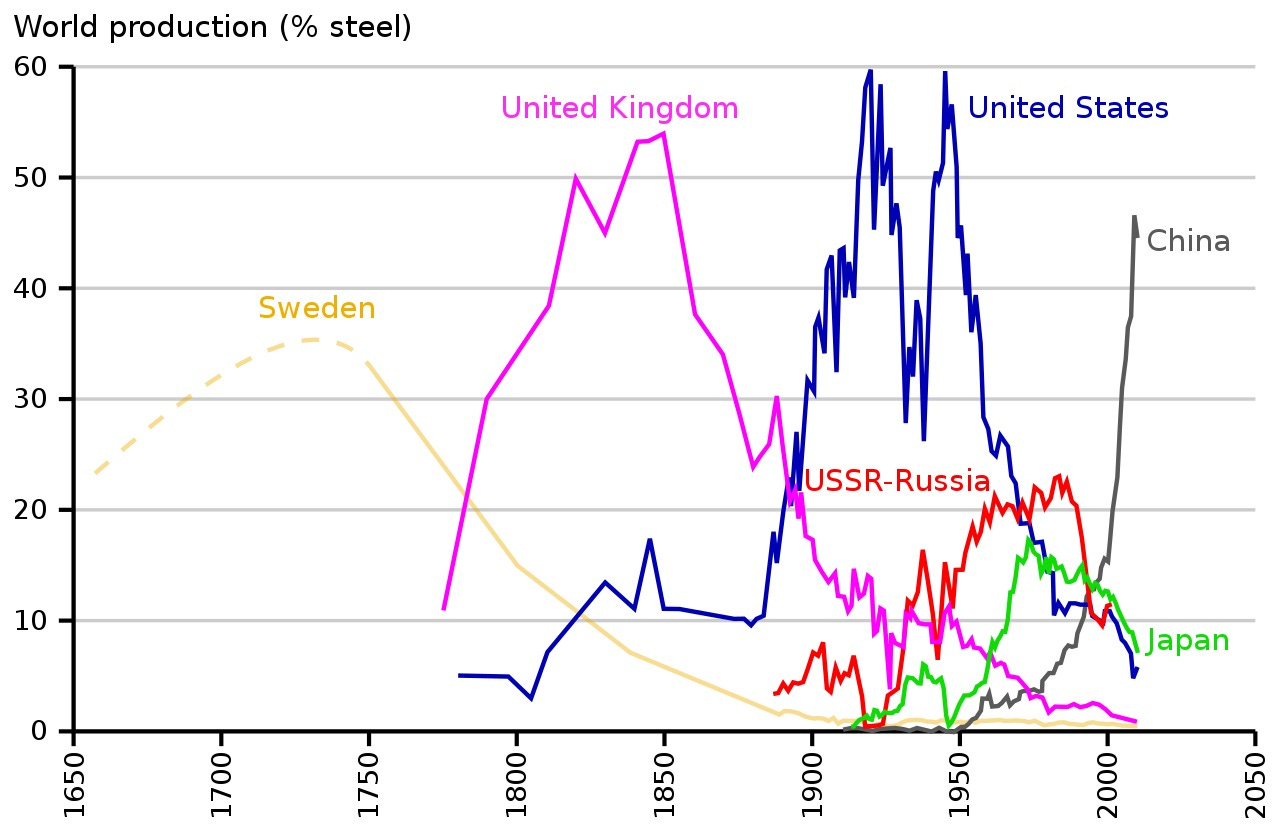

Relative to global production, though, China’s steel binge was actually not unique. The UK and the U.S. were both even more dominant in steelmaking in earlier eras:

For the U.S., this dominance came during our era of rapid growth, when we were building our railroads, cities, and highways, and when we were dominant in the manufacturing of autos and machinery. Japan and the USSR also had smaller booms related to their own heydays of extensive growth.

Now, the U.S. mostly just maintains our highways and railroads, and builds relatively little new housing. Our difficulty building new infrastructure, urban apartment buildings, and factories — due primarily to the ability of NIMBY citizens to hold up any development project — is by now well-known. Every country eventually saturates itself with highways and trains and office buildings, but the U.S. has become unusually dysfunctional since the 1970s in terms of our ability to build things.

And on top of all that, the U.S. has de-industrialized to a significant degree. Our domestic auto production has been declining in terms of absolute number of vehicles for decades, and our share of global machinery manufacturing collapsed decades ago. Overall industrial production in manufacturing is lower in 2023 than it was in 2006:

Note that this is an absolute level of production, not relative to GDP or anything like that. Also note that this is on top of whatever efficiencies manufacturers have been implementing in order to use fewer expensive and heavy materials — for example, using more aluminum and less steel in cars.

In general, the U.S. is also just much less manufacturing-intensive than other major economies:

In other words, the fairly obvious explanations for most of the decrease in U.S. steel production are:

The U.S. finished our basic nation-building spree long ago,

The U.S. has suffered from a lack of construction due to NIMBYism, and

The U.S. has become unusually de-industrialized.

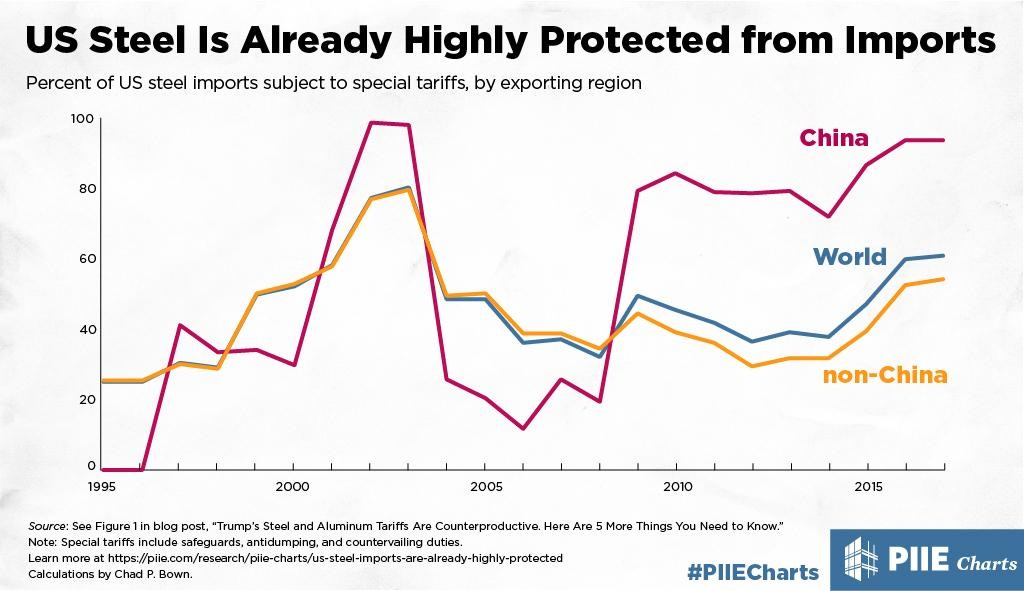

Now, it’s possible that there’s reverse causation at work here. If U.S. steel production costs were unusually high, it could have sped de-industrialization and hurt the construction industry as well. In order for this to happen, U.S. manufacturers and construction companies would have to be barred from simply importing cheaper foreign steel to compensate. But in fact, that probably is the case; steel is an extremely protected industry.

But although something like this might have been going on in the 70s and 80s, I doubt this is a big part of the story in recent years. As we saw in the last section, U.S. steelmakers boosted their productivity quite a lot in the 1990s and early 2000s, and the result was a steel export boom in the late 2000s and 2010s. It thus seems unlikely that the U.S. steel industry was so dysfunctional over the last three decades that it literally caused U.S. stagnation and deindustrialization.

A far more likely story is that the U.S. simply stopped using a lot of steel, so we stopped making a lot of steel.

That doesn’t mean this was a good thing — NIMBYism has been a disaster for the U.S., and I think deindustrialization has been a net negative as well. But what it does mean is that we should stop thinking about steel as something that’s desirable in and of itself, and start thinking of it primarily as an input into things like buildings, cars, and machines. Instead of throwing up steel tariffs like Trump did, or trying to protect the ghost of U.S. Steel from Japanese buyers like Fetterman is doing, we should be trying to boost the industries that use steel. And not so we can save some steelmaking jobs, but so we can have the stuff that those industries produce.

We should be trying to promote new construction of housing and solar plants. We should be making it easier to build factories, trains, and highways. We should be subsidizing consumer demand in order to speed the transition to electric vehicles and other green technologies. And we should probably be trying to rebuild our machine tool industry, in order to reduce the risk of excessive reliance on China.

And if we do those things, I predict that we’ll see a revival of the American steel industry as well.

Update: Brian Potter has a great post about the history of U.S. Steel, which apparently stopped innovating long, long before the American steel industry as a whole went down.

"And on top of all that, the U.S. has de-industrialized to a significant degree. Our domestic auto production has been declining in terms of absolute number of vehicles for decades, . . ."

You should do a deep dive into U.S. ship building capacity next. I wonder if the same causes has led to that decline as well.

See https://www.businessinsider.com/us-navy-chinas-shipbuilding-capacity-200-times-greater-than-us-2023-9

I love these US-centric economy posts. I'd love more articles on what the US actually makes, our strengths/weaknesses as an economy. Clearly the US creates a lot of value, but what exactly?