The next phase of globalization is going to be awesome

The party isn't over yet. It's just going to look a little different than before.

The G-20 summit in New Delhi felt like the dawn of a new era in both global economics and geopolitics. It was India’s time to shine; the host country was the darling of developed and developing economies alike. U.S. President Joe Biden announced a new infrastructure investment corridor centered around India, and declared that the U.S. supports India’s bid for a permanent UN Security Council seat. Meanwhile, India released a joint statement with Brazil and South Africa to work together on geopolitics. Basically, the G-20 can be summed up by this photo:

Meanwhile, the summit was just as notable for who wasn’t there — Xi Jinping, whose absence was the first for a Chinese leader in the history of the G-20. His refusal to come might have been a snub to India, or simply to any international organization not dominated by China, or both.

Regardless, it was highly symbolic. The locus of industrial globalization is shifting from China to a bunch of other developing countries. India is at the center of this, along with other countries in South and Southeast Asia. That will open up opportunities for developed countries like the U.S., Japan, South Korea and Europe to invest and to open up new markets. And the new wave of globalization will create opportunities for resource exporters like Brazil and South Africa to sell their materials to someone other than China. But China itself won’t vanish behind an iron curtain; it’ll play its own important role in this wave of globalization, investing in and exporting to the next crop of developing nations.

There’s a narrative going around out there that globalization is over, that decoupling will carve up the world into smaller trading networks, or even into isolated autarkic nations. And there’s another narrative that economic development is over, and that China was basically the last country to industrialize. Both of these narratives are wrong. In fact, globalization is simply changing form, as it has many times in the past. Investors and executives at multinational companies should be getting ready for the next round.

Why the shape of supply chains changed, and why it will change again

In the 1980s and 1990s, “globalization” generally meant that the developed countries — the U.S., Japan, Europe — and a few still-developing Asian countries like South Korea and Taiwan would sell each other complex manufactured products like electronics and cars (and some services), and that the rest of the world would sell them either natural resources, or simple low-value manufactured goods like clothes and fabrics. If you remember the 90s, you’ll remember that this is how people thought about international trade.

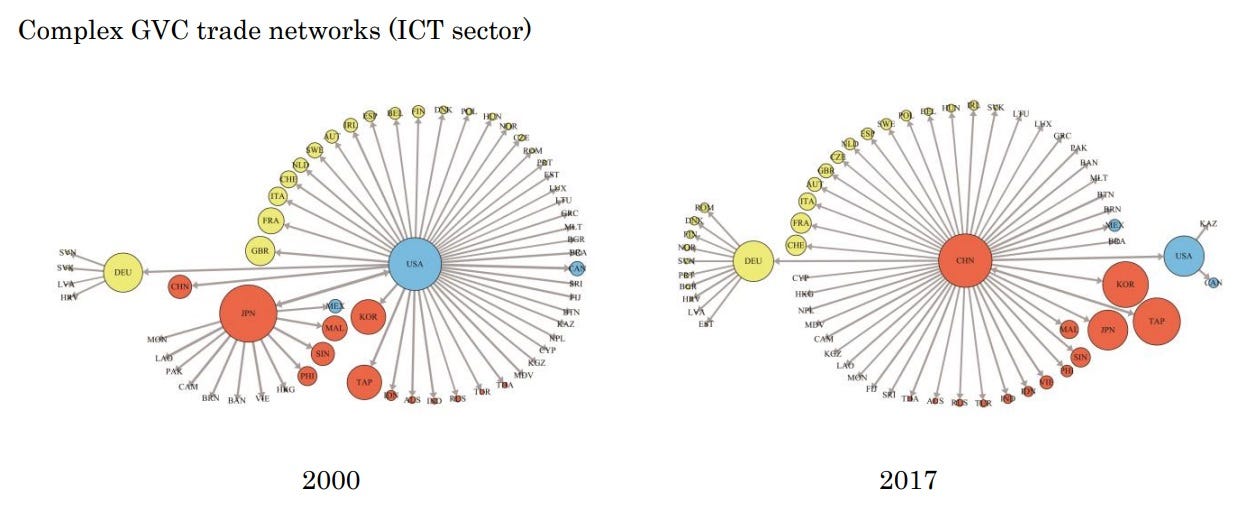

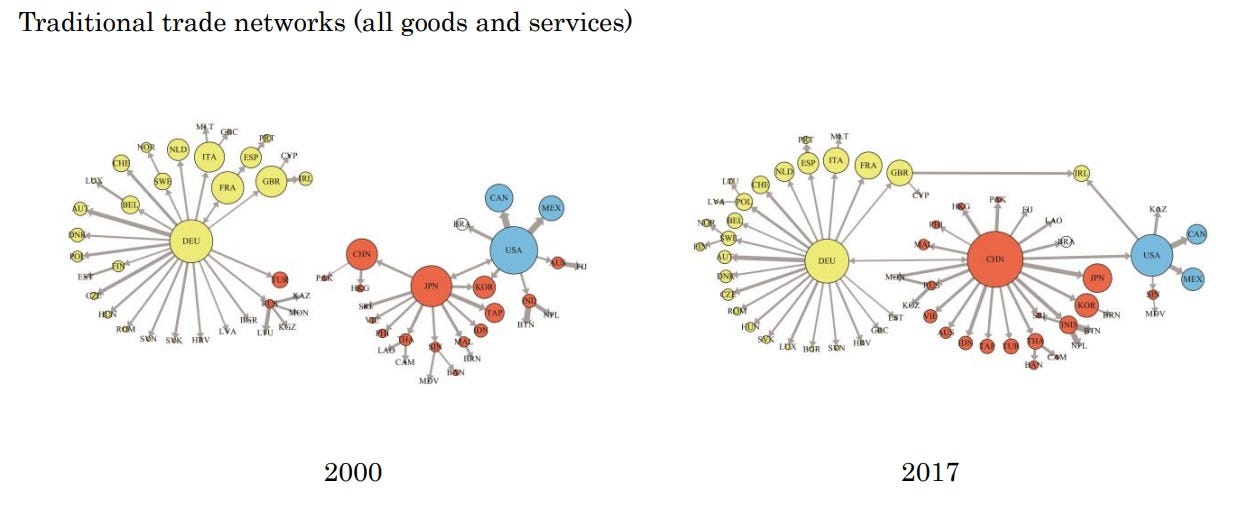

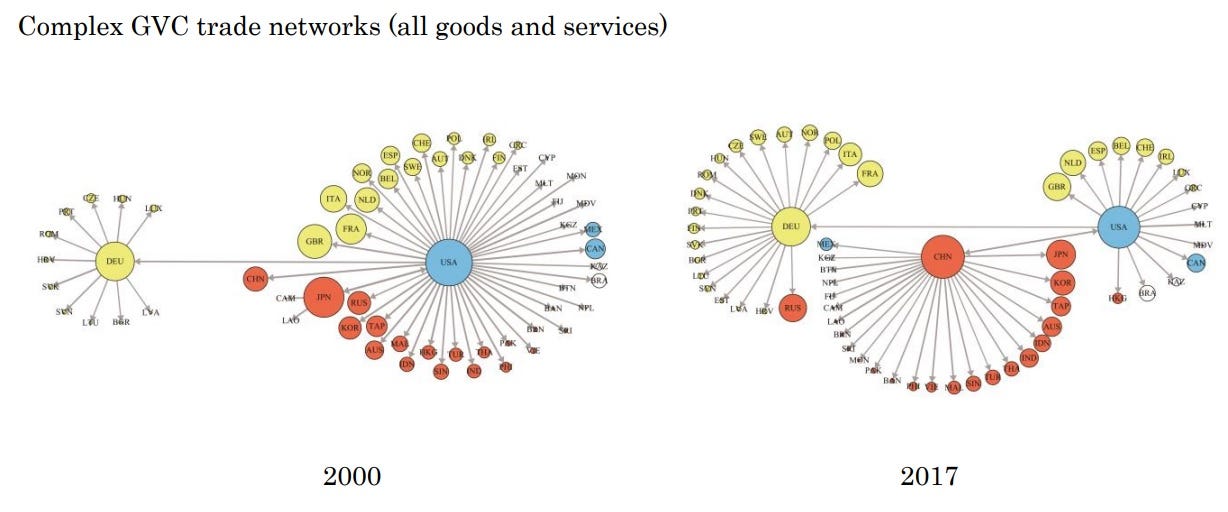

Then around the turn of the century China joined the WTO, and everything changed. China became the workshop of the world, offering unbeatable prices in the 00s and unbeatable scale in the 10s (and the tantalizing promise of market access in both decades). Global trading networks that had centered around the U.S., Japan, and Europe now all went through China. Meng, Ye and Xiao (2019) try to visualize this shift, depicting trade links in terms of both gross exports and more complex chains of value-added. Here are just a few of their visualizations, which clearly show how China came to dominate globalization both overall and in the crucial electronics sector:

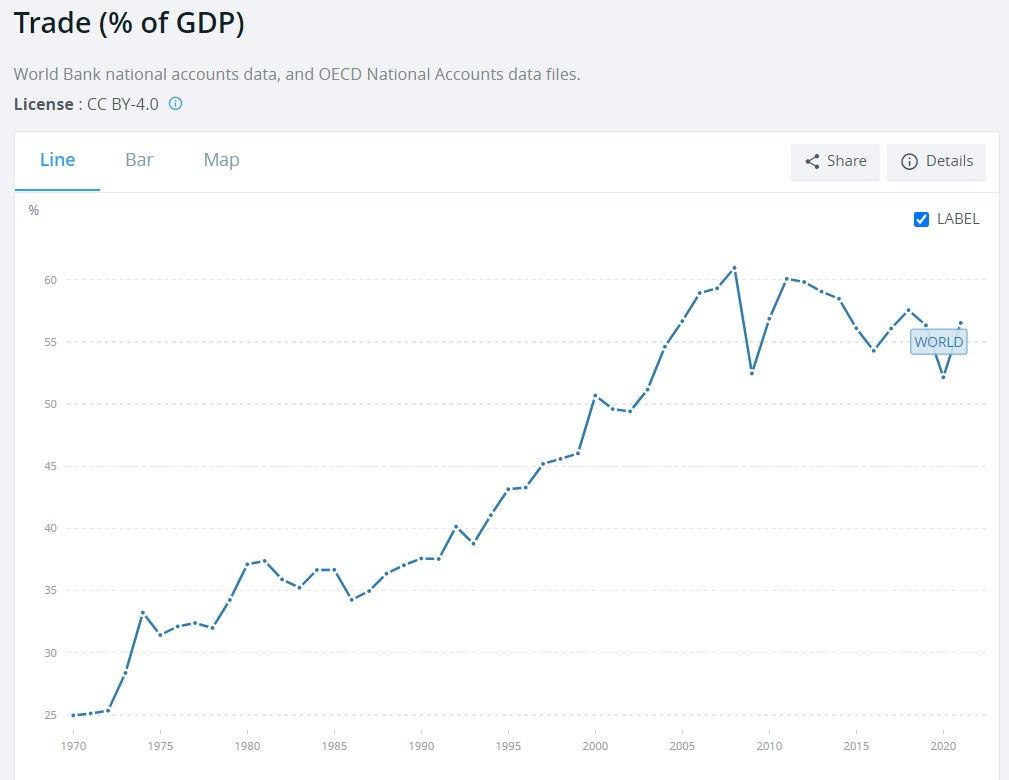

But after the the financial crisis of 2008, something changed. World trade as a percentage of GDP plateaued and started falling.

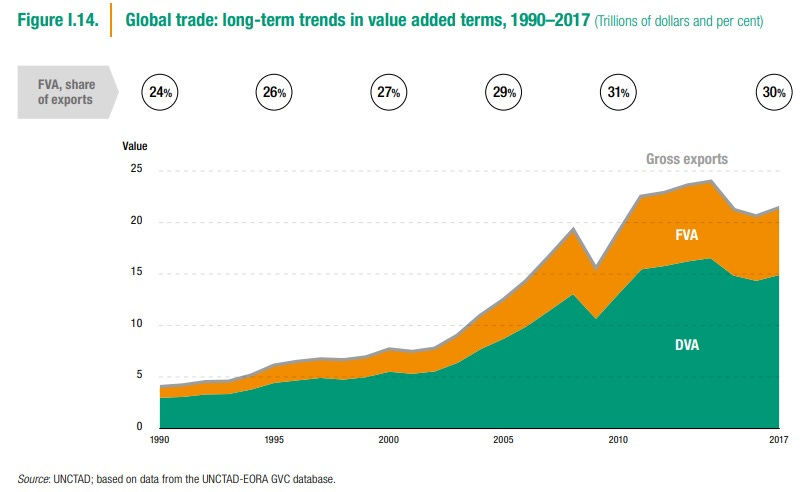

Not only did total trade plateau, but the proportion of foreign value-added plateaued soon afterwards. Foreign value-added is basically a measure of supply-chaining. If you import a chip from Taiwan and a screen from South Korea and use them to make a phone in China — as was standard practice in the 2000s — the value of the chip and the screen are counted in “foreign value-added”. But around 2010-12, this practice plateaued — supply chains were no longer getting more complex.

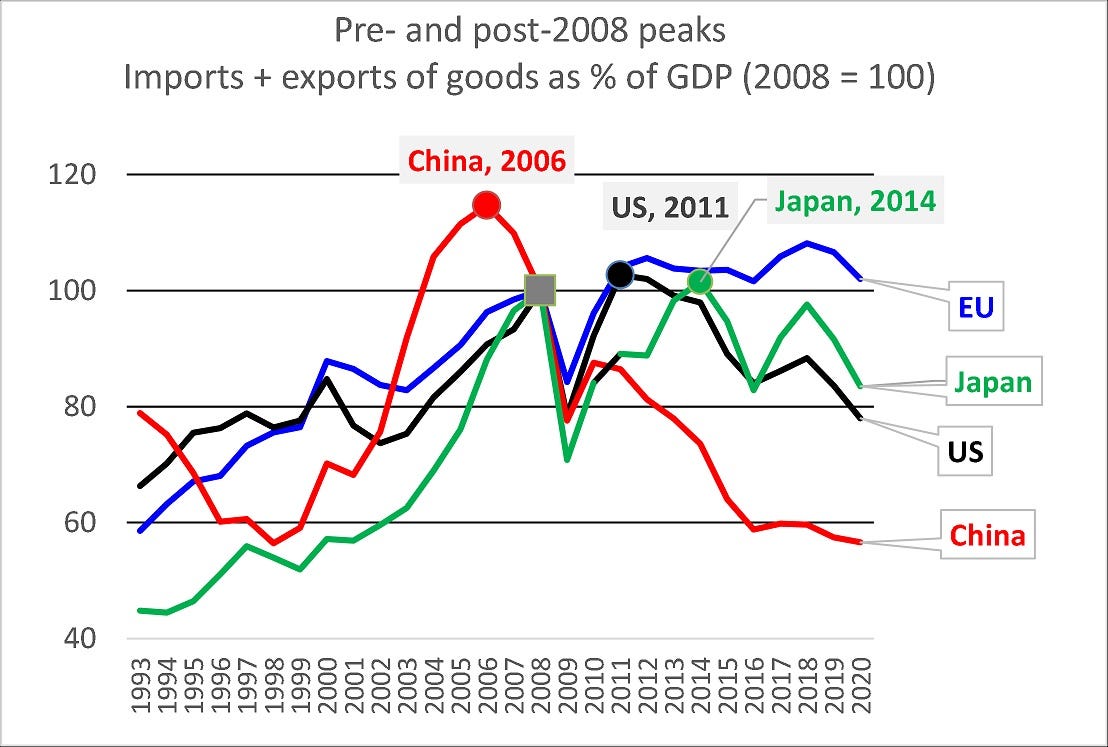

What happened? Why did globalization hit a ceiling? Obviously there were multiple factors, including the fact that the developed countries experienced economic weakness and couldn’t buy as many imports. But a big part of the answer is that that China’s role in the global economy shifted in the 2010s. Its export growth slowed down, and it started making more of its parts and components domestically instead of importing them from other countries. This is from a 2019 McKinsey report:

As consumption grows, more of what gets made in China is now sold in China. This trend is contributing to the decline in trade intensity. Within the industry value chains we studied, China exported 17 percent of what it produced in 2007. By 2017, the share of exports was down to 9 percent…

China’s rapid growth has made it a major part of virtually every goods-producing global value chain…But as its economy has matured, China has moved beyond assembling imported inputs into final products. It now produces many intermediate goods and conducts more R&D in its own domestic supply chains. This is the second factor dampening global trade intensity in goods. In computers and electronics, for instance, Chinese companies are developing the kind of sophisticated smartphone chips that China once imported from advanced economies. Building more vertically integrated domestic industries enables China to capture more value added[.]

Here’s a good graph that shows just how much of “slowbalization” was just China:

Since 2008, we’ve been living in a strange interregnum. China-led globalization has halted, but the next wave hasn’t yet begun.

Or rather, it hadn’t begun, until 2022.

The next big investment opportunity

I’ve written a bunch about how and why “decoupling” started. If you want to read what I’ve written about that, start here:

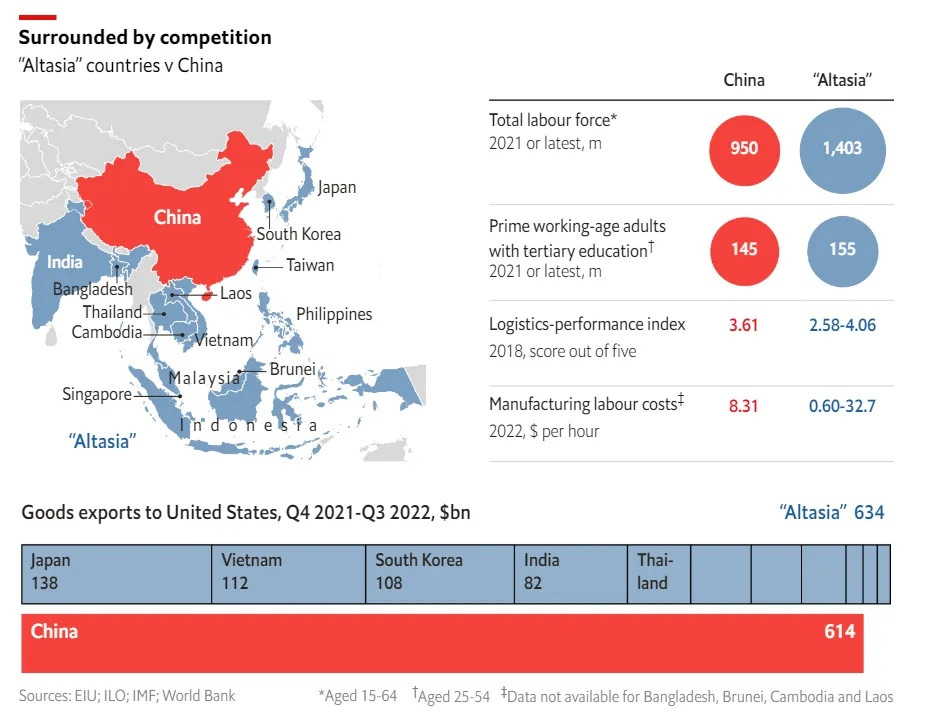

But now that decoupling is beginning to gather steam, multinational companies are starting to pay attention to countries that represent alternatives to China, both in terms of production platforms and markets for their goods. Earlier this year, The Economist suggested that Asian countries other than China represent the next big opportunity, coining the term “Altasia”:

The Altasia concept actually includes both developing countries and rich Asian countries like Japan, South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan. The idea is that complex high-value things like advanced semiconductors will be made in the rich countries, while more labor-intensive cheap stuff will be made in the poorer countries. An editorial in BusinessKorea lays out the thesis more explicitly:

A case for Altasia is that an alternative supply chain to replace China can be built if Korea, Japan, and Taiwan provide advanced technology and capital, Singapore provides financing and logistics, and India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines provide labor and resources.

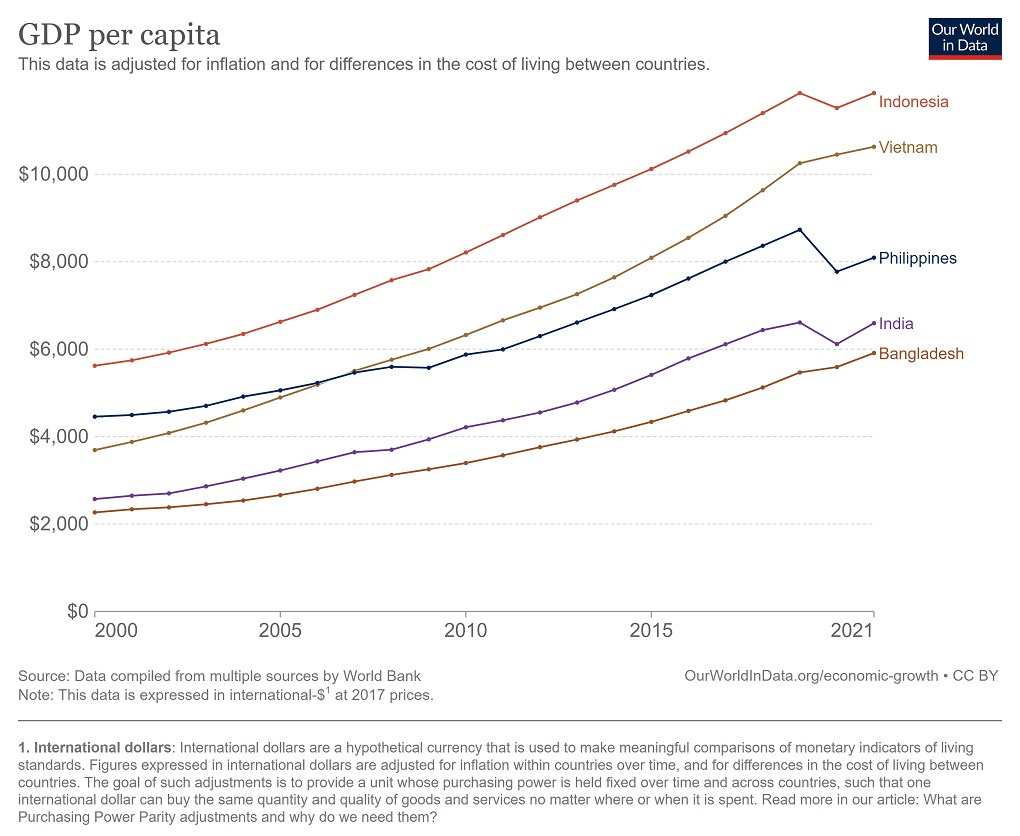

This sounds a lot like the globalization of the 90s, before China took over everything. But I think this simple vision severely underestimates the developing countries of Altasia. They will obviously do a lot of low-value assembly work — slapping together components made in rich countries to make phones and TVs and laptops. But I think they’ll climb up the value chain faster than people realize.

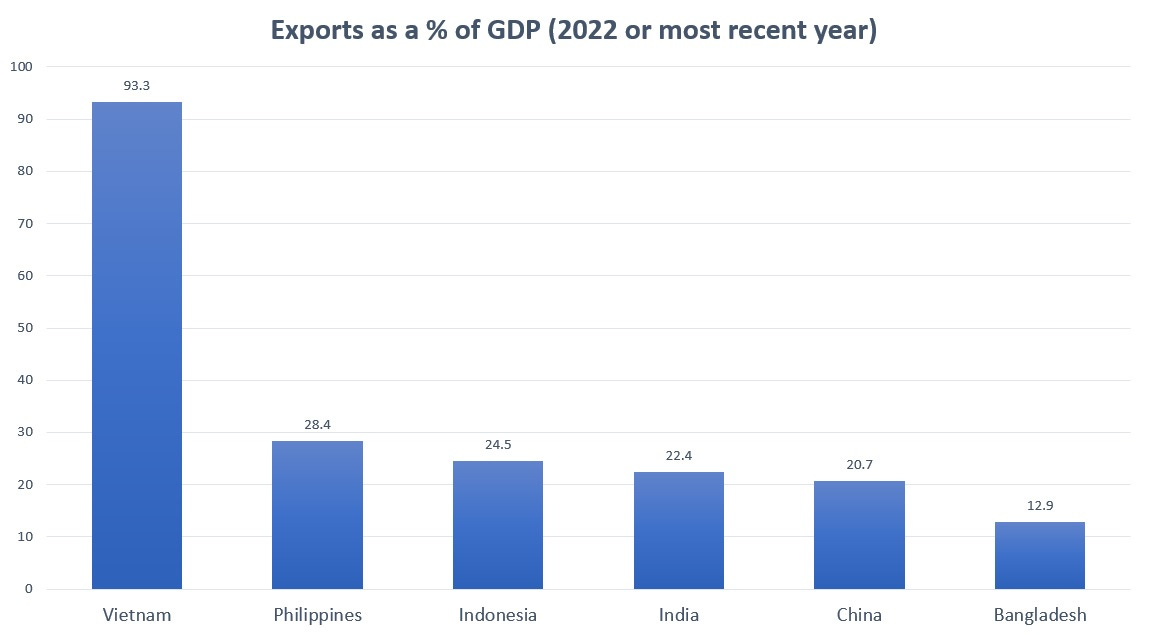

First of all, most of the developing countries of Altasia are pretty export-oriented. Vietnam is the champion here, but India, Indonesia, and Philippines are more export-intensive economies than China at this point. And I predict these shares will grow, as multinationals shift FDI to Altasia.

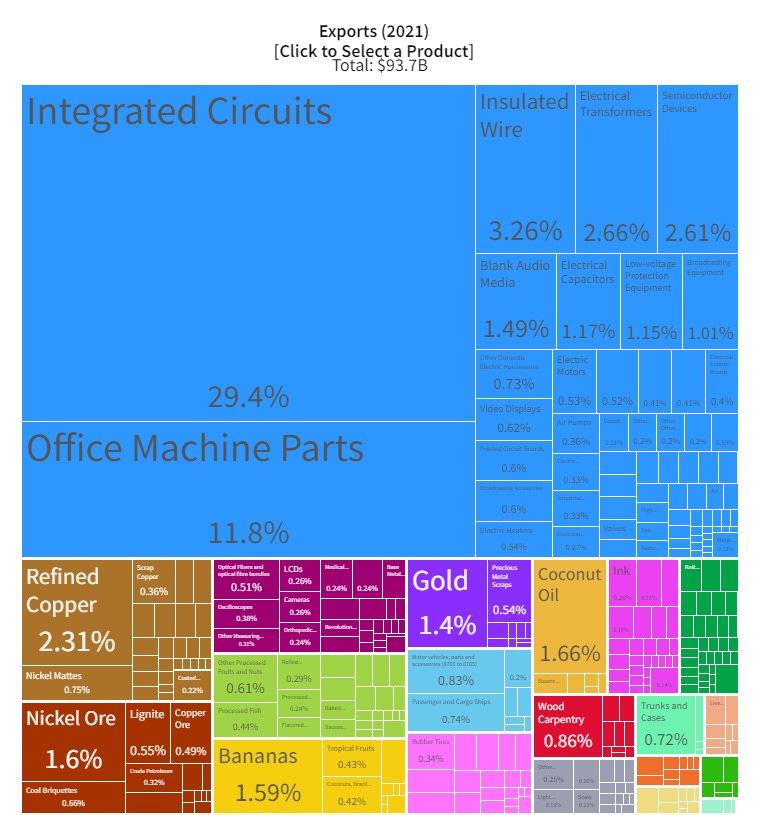

Exporting is probably very important for developing countries to raise their productivity levels, since it pushes their companies to learn global business practices, explore bigger markets, import foreign technology, and so on. And although some Altasian countries like Bangladesh focus on simple labor-intensive goods like shirts and pants, others seem primed to become players in the all-important electronics industry. For example, you don’t really think of the Philippines as an electronics powerhouse, but check out what it exports in terms of physical goods:

In fact, the image at the top of this post is of a Japanese-owned electronics factory in the Philippines. Take a look at the machinery; it is very much not just a bunch of low-paid laborers standing around slapping together some plastic casings by hand. Meanwhile, it seems like every day, companies are lining up to make laptops and electronic components in India.

Electronics is the most important industry for both supply chains and globalization, because it’s complex, because it’s high-value, and because it’s light — you can ship a heck of a lot of value very cheaply in the form of a box full of computer chips, and this also means it makes sense to route production through a bunch of different countries. And Asia has become the beating heart of the global electronics industry, with the U.S. and Europe as peripheral players. But “Asia” here doesn’t just mean “China” anymore; India, Vietnam, Philippines, and probably Indonesia and Bangladesh will become very important players, while much of the best technology remains in the hands of Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and Singapore (and to a lesser extent Malaysia).

If you’re in electronics, Altasia seems like it’s clearly the place to be right now, and this is a very good sign for the continued catch-up growth of the poor countries in that region. That’s why I expect these smooth growth curves to continue:

Now, there’s a second important piece of globalization that I’m still not sure will relocate to Altasia, and that’s heavy industry — of which autos and other vehicles are the most important part. Heavy industry also tends to favor supply chains, but it depends on a lot of inputs like steel, other metals, chemicals, etc. that are often low-margin industries that require a lot of capital and tend to create a lot of pollution if not properly managed. Heavy industry is another area in which China has become key to global supply chains — even more so now that vehicles are shifting toward battery power, allowing China to leapfrog rivals in developed nations. Whether or not countries like India, Indonesia, and Vietnam can compete in heavy industry will depend a lot on their industrial policy.

But in any case, I expect South and Southeast Asia to be the next great locus of global supply chains and of catch-up industrial growth. This will create some headaches for multinational companies who have become used to lazily assuming that all manufacturing will be done in China. But ultimately it will mean a ton of opportunity for them, because Altasia-centric trade will look more like the truly global supply chains of the 90s, than the inward-turning China of the 2010s. Companies will have to put in the legwork to decide where to site production, but ultimately the increased optionality, the Asian electronics clustering effect, and the power of comparative advantage will be more important than the logistical difficulties.

In other words, the shift from China to Altasia should reignite the kind of globalization that we were used to in the late 20th century. The party isn’t over yet.

The deep theory of globalization

I guess I should also say something about the economics of globalization, and why it favors the kind of shifts that I’m predicting. Beyond things like clustering effects that are specific to a technology and a place, there are reasons to think that globalization in general is a process that builds on itself.

A very simple theory is the “flying geese” idea, developed in Japan by economists such as Akamatsu Kaname in the 1960s and Ozawa Terutomo in the 1990s. The basic idea is that multinational companies keep looking for cheap places to locate their production, and that the countries they invest in eventually climb up the value chain. When they climb up the value chain, they become investors in the next cheap production location. So as an example, at first you just had Japan making electronics in Asia, then they invested in cheap factories in Korea and Taiwan, then Korean and Taiwanese companies learned how to do the complex stuff that the Japanese companies could do, and then they all started investing in Malaysia and Thailand and China, etc.

This is a very simple concept. You can apply it to any technologically complex industry, not just electronics. All it requires is that A) companies seek cheap production overseas, and B) people in any country learn how to do more technologically sophisticated things over time. As long as companies keep investing and local producers keep learning, you end up with more and more countries looking to invest in the next cheap production location. So globalization just snowballs.

A more sophisticated version of this theory is the New Economic Geography, which helped win Paul Krugman a Nobel Prize. In a 2001 book, Krugman, Fujita Masahisa, and Anthony Venables laid out a version of the theory with multiple countries, where capital can move across borders but workers can’t. Over time, growth proceeds in a series of local cascades — when costs rise to a certain point in the developed regions, economic activity suddenly floods into the nearest poor region, raising its living standards via trade with the rich countries. It’s a staggered process of global development where each country or series of countries basically has to wait its turn in line. This is a much more abstract model than the “flying geese” idea — it doesn’t even have capital investment! — but it ultimately delivers the same result.

(It’s also worth mentioning the gravity model of trade, which is one of the most empirically successful models in all of economics. It’s a very simple model that says that countries that are near each other and have higher GDP are likely to trade more. That doesn’t tell us about how countries will develop and grow, but it does suggest that South and Southeast Asia’s proximity to the economic powerhouses of East Asia will give the region plenty of trade opportunities.)

These theories — you can decide how much to believe them — have two main implications. First, industrialization and integration into global supply chains shouldn’t be seen as a contingent process, where countries succeed or fail purely based on their domestic policies; although the groundwork should be properly prepared for multinational investment, ultimately it’s the logic of costs and geographic proximity that drive economic activity to poorer countries. In other words, sometimes it’s just a region’s time to develop, and as long as countries meet some minimum standard of investability (i.e. not being North Korea or Myanmar), they can reap some benefit from the opportunities existing in their local neighborhood.

Second, each new round of developed countries is a key contributor to the next wave of development, both through investment and through the markets it provides. In Altasia, that means China has an important role to play. Chinese companies will look to Southeast Asia as a production base as their costs rise; already, Vietnam is importing more intermediate goods from China to assemble and sell to rich countries. China’s markets, to the degree that it allows import competition, will also be important for companies in Vietnam, India, etc.

In other words, it’s wrong to see this next wave of globalization as a shift of economic activity away from China. Yes, FDI in China will drop, but China will help drive the next wave in totally new and different ways from what it did in the 2000s. It’s a developed country now, and it will start behaving like one.

So I think the future of globalization is bright. Even if the spread of industrial activity to South and Southeast Asia gets interrupted by a major war or hobbled by climate change, the spread of economic activity from region to region is a deep and inexorable economic force that is very hard to deny. This party isn’t over yet.

Great article, it sounds like the future of "globalization" is just deepening investment in Asia without being super focused China. Doesn't sound like this is Latin America's time yet, which is a real shame because Latin America should be an easier destination for America & Canada. But as you pointed out the agglomeration, talent, and supply chains are already in East Asia.

One thing though. In our "globalized world" its more regional - 85% of world trade is concentrated in North America, Europe, and East Asia & Pacific while 15% is in Middle East, South Asia, Russia, Central Asia, and Africa.

Here's the breakdown of the three regions:

The EU, UK, Swiss +& Sweden alone is around 40% of world trade (Europe region)

East Asia, South East Asia, & Pacific is around 30% (East Asia region)

USMCA is around 15% (North America region)

Totaling 85% of global trade

In Shannon O Neil's book "The Globalization Myth" she would call this period - regionalization. Especially since half of East Asian trade is within East Asia, two-thirds of European trade is within Europe, and 40% of North American trade is in North America.

What do you think the proportions would be if in Globalization 2.0? I suppose since India and Bangladesh are rising do you think South Asia would become a fourth trade hub? Does "Globalization 2.0" really just mean South Asia emergences the fourth trade hub just like Globalization 1.0 was really just the emergence of East Asia?

Article/Visuals/Data for Global Trade proportion:

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/who-dominates-global-trade

Article/Visuals/Data for Interregional Trade:

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/who-dominates-global-trade

Another fantastic article... thanks.... Two points:

1) On Xi not visiting... there is a simpler explanation... China is a mess, he has political opponents, leaving the country right now may not be viable. Most dictators are overthrown right after vacations and overseas trips.

2) The economic analysis is very good... the innovation/technology analysis is missing. The nature of technology acceleration is that the nature/value of "cheap" labor is falling quickly... in favor of robotization. In this world, a small number of large ecosystems will gain investments for regional manufacturing. The North American version is very likely to be Mexico. There will be one (perhaps two) in Asia, and one in Europe. This is not to say that the Mexican hub won't have Chinese owners or the SE Asia hubs won't have American/European owners.

Overall, the actual nature of the work done by the labor will shift significantly.