Corporations aren't the reason your rent is too high

The antitrust progressives are just wrong about this one.

Donald Trump is choking off U.S. manufacturing with tariffs, replacing statistical agency personnel with apparatchiks who will manipulate data to make the President look good, and so on. Yet some progressives remain convinced that the key to winning back the country is to harness a wave of populist anger by attacking big corporations. I’m not sure I see the political logic there, but I guess I’m not much of an expert on politics.

Anyway, I’m sympathetic to the notion that monopoly power has increased in the U.S. economy since the turn of the century, and that this is making life harder for some Americans. But corporate power is simply not the cause of many of the problems regular Americans face — there are a lot of other things going on too. And because antitrust progressives insist on fitting every problem into the paradigm of corporate power, they end up believing a number of false things about the world. One example I’ve written about before is that of health insurers, whom antitrust progressives view as the chief architect of everything that’s wrong with the U.S. health system; in fact, these companies make almost no profits and are fairly efficient.

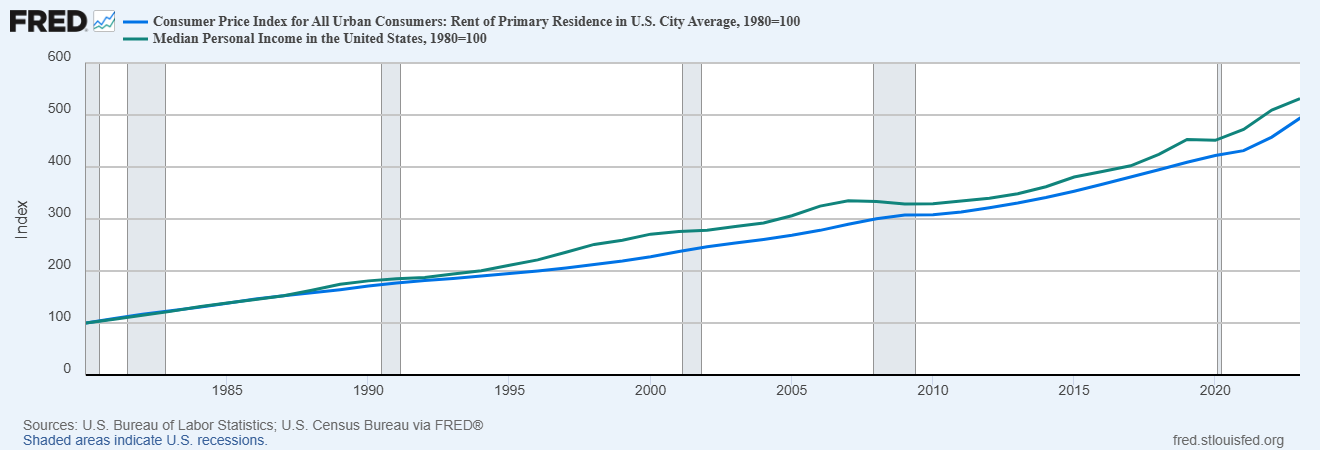

Another important example is the housing market. Overall, housing has not actually gotten more expensive throughout America; if you compare median personal income to the CPI measure for rent of primary residence, you’ll see that income has actually gone up slightly faster than rent since 1980:

But in the attractive cities where most people would like to live if they had the choice, rent has gone up much faster than in the decayed Rust Belt cities and small towns where most Americans would prefer not to live. The rental crisis is a local one, but it’s real.

Abundance liberals blame this problem on lack of housing supply, and support YIMBY policies to build more housing in cities. But although some progressives are coming around on this, many are strongly opposed to the abundance agenda. Instead, they want to blame high rents on powerful companies who buy up all the houses and then jack up prices.

A few years ago, this manifested as a panic about BlackRock buying up large amounts of the housing stock in America. This was a silly mistake; BlackRock doesn’t buy homes, except indirectly by investing in stocks called REITs. People were probably thinking of Blackstone, a much smaller asset manager with a similar name, which does buy up homes.

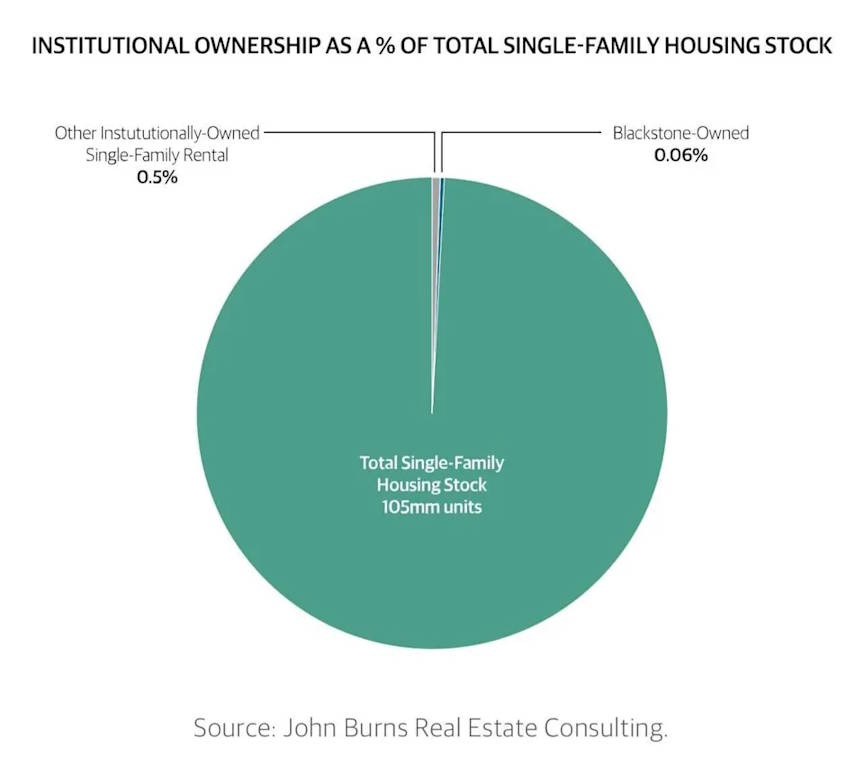

In addition to this silly mistake, the broader panic just wasn’t based on facts. In 2021, Derek Thompson did a great job of debunking the myth:

The U.S. has roughly 140 million housing units, a broad category that includes mansions, tiny townhouses, and apartments of all sizes. Of those 140 million units, about 80 million are stand-alone single-family homes. Of those 80 million, about 15 million are rental properties. Of those 15 million single-family rentals, institutional investors own about 300,000; most of the rest are owned by individual landlords. Of that 300,000, the real-estate rental company Invitation Homes—in which BlackRock is an investor—owns about 80,000. (To clear up a common confusion: The investment firm Blackstone, not BlackRock, established Invitation Homes. Don’t yell at me; I didn’t name them.)

Megacorps such as BlackRock, then, are not removing a large share of the market from individual ownership. Rental-home companies own less than half of one percent of all housing, even in states such as Texas, where they were actively buying up foreclosed properties after the Great Recession. Their recent buying has been small compared with the overall market.

The actual number of homes Blackstone (or BlackRock) was buying was tiny — far too tiny to affect rental prices in any significant way, except perhaps in a few very localized areas.

But somehow, despite its lack of connection to reality, the meme stuck around, and the size of the problem grew as the story was repeated around the internet. There are still people who think BlackRock is buying up much of the housing in America. In fact, even some right-wingers are convinced of this:

The exact form of the claim varies. Sometimes it’s 44% of the housing that the evil corporations are buying up, sometimes it’s just 20%. Sometimes it’s BlackRock alone that’s responsible, sometimes it’s the private equity industry:

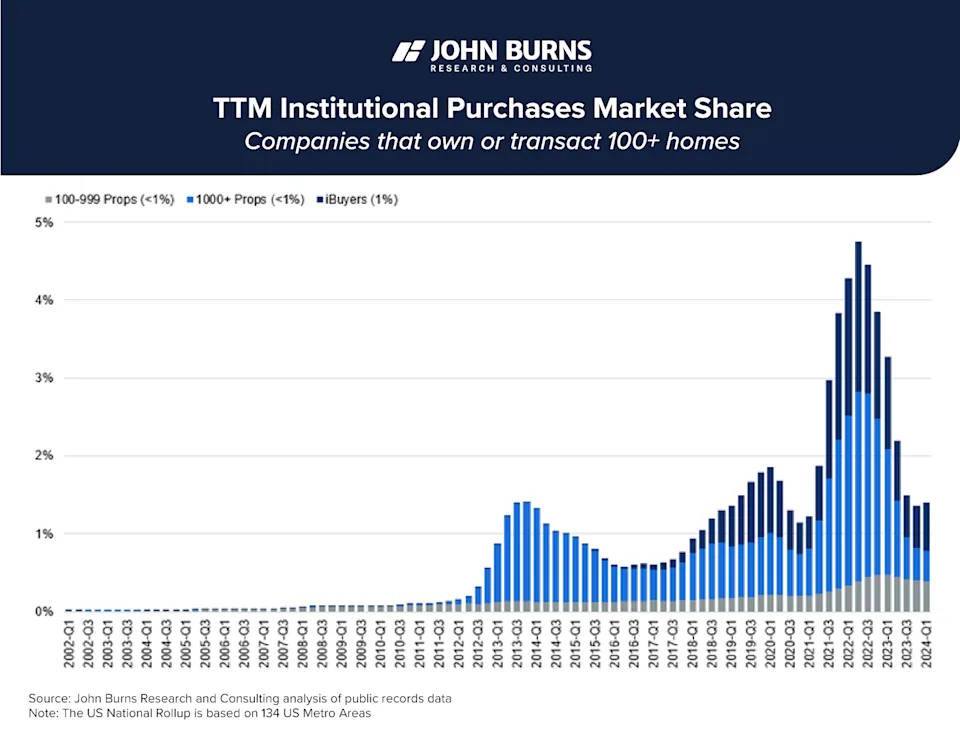

But the meme remains false. Many news outlets have debunked it over the years. For example, Logan Mohtashami posted the following charts in Yahoo Finance in 2024:

The first of the two charts shows that institutional buyers — which includes private equity, BlackRock, etc. — own only a tiny sliver of the homes in America. The second chart shows that there was a corporate home-buying spree in 2022, but it never even hit 5% of home purchases at its peak — far lower than the rumors claim.

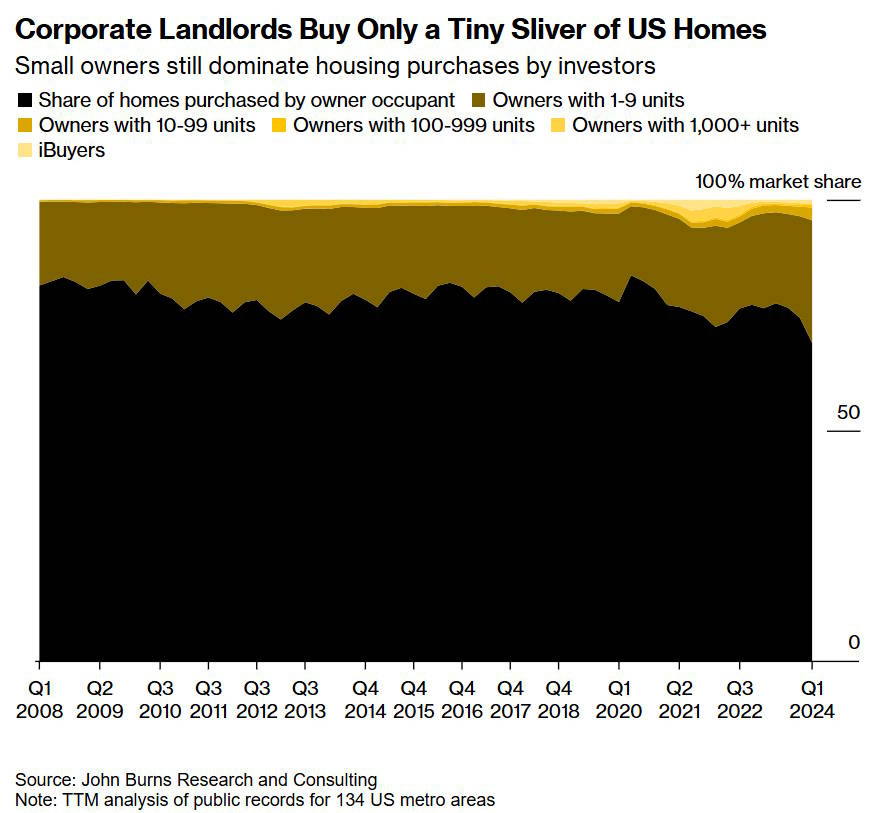

Kriston Capps also wrote a great debunking of the “corporate landlords” myth in 2024. Here was his chart:

Almost zero of the U.S. housing stock gets bought by owners who own more than 9 units. Corporate landlords just aren’t significant enough to be driving the rental crisis in America’s most desirable cities. (Of course, this doesn’t stop anticorporate types from mocking the very idea that high rents are caused by something other than market power.)

In fact, it gets even worse for the antitrust story here. It turns out that corporate landlords probably don’t even do what antitrust people think they do! The common story is that corporations buy up all the houses in an area, thus creating a local monopoly, and using that local monopoly to jack up rents — which in turn causes gentrification and pushes poor people and minorities out of the neighborhood.

Except Konhee Chang, an economics job market candidate, found evidence that corporate landlords actually make housing cheaper for lower-income folks, and lead to diversification instead of gentrification!

Using property-level data on tenants, home prices, rents, and acquisition timing, I show that increasing rental supply in American suburbs, where rentals are scarce and expensive relative to owner-occupied housing, reduces segregation by enabling lower-income, disproportionately non-White renters to move into neighborhoods where they otherwise could not afford to own. In response, nearby incumbent households are more likely to move out, perceiving renters as a disamenity. Large-scale landlords expand rental supply by converting owner-occupied homes into rentals, exploiting cost efficiencies from geographic concentration.

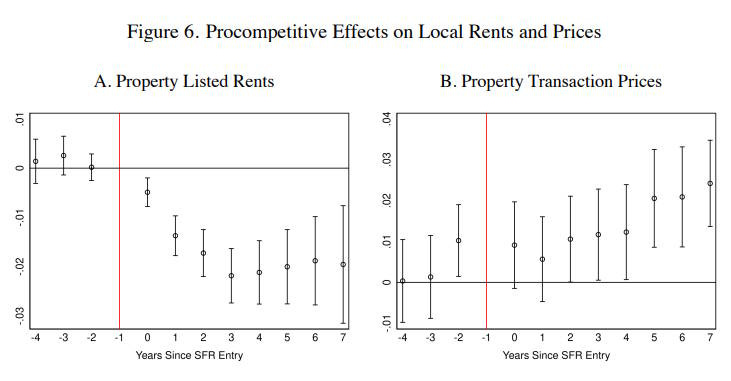

Chang found that corporate landlords drive down rents and slightly raise the price of buying a house:

This is only to be expected, since what the corporate landlords are doing is buying up housing (which raises purchase prices because it increases demand) and converting it to rental units (which lowers rents because it increases supply).1

So as far as we can tell, corporate landlords — at least, right now — aren’t causing the harms that the antitrust progressives (and some right-wing pundits) claim. The cause of the housing crisis in desirable metro areas must lie elsewhere. The obvious culprit here is just supply limitations — i.e., land-use regulations and NIMBYism. And the obvious way to address that is the abundance agenda.2

For antitrust progressives, the problem with that conclusion is that it doesn’t place the blame on their class enemies. If corporate power isn’t the problem when it comes to high rents, then it means fewer opportunities for progressives to harness populist rage against the business class. In addition, antitrust progressives probably still believe that they can harness a wave of anticorporate populist sentiment to buoy Democrats back to victory. I would be very surprised if that strategy worked.

But in any case, the story that corporate landlords are making American housing unaffordable is simply false. It’s just another free-floating memetic myth that keeps getting in the way of our ability to solve our very real problems. And the zeal with which antitrust progressives have embraced and propagated that myth should make us a little more pessimistic about their ability to accomplish positive change in the current political economy.

This ought to be an open-and-shut case, but a progressive economist popped up to try to argue:

As I explained, the reason welfare goes down in the paper is that corporate landlords push down prices enough that poor Black and Hispanic people are able to move in to previously richer, whiter neighborhoods. Chang, the author of the paper, assumes — probably correctly — that rich white homeowners do not like to live next to poor Black and Hispanic renters. And so the rich white homeowners lose utility from corporate landlords, because they no longer get to exclude people from their neighborhoods along racial and class lines!

Somehow, this point was lost on the progressive economist, who ended up defending white flight as a socially desirable thing.

Of course, even the abundance agenda won’t totally be able to negate the local impacts of big increases in demand for housing in coastal cities. Demand for life in those cities is just extremely high. But supply increases will blunt those impacts, and create affordability further from the center of New York City, San Francisco, etc.

It's possible that economic populism is complete bullshit but would also be an effective electoral strategy for the Democrats. After all the American electorate has hardly shown itself to be rational organ of truth-seeking over the past decade.

This seems to be tilting at progressives. You know, the people in power, the ones who have control of courts, the legislature, and presidency... Oh wait...

I'm sure there were lots of problems with the platform of German Communists in 1934, but they weren't the problem at that moment.

Also, the problem with American insurance companies is their role as middlemen who add no value to patient care. Making low profit isn't a defence. Didn't Amazon, that altruistic company, run at a loss (on paper) for the first 20 years?

Look up medical loss ratios. Look up how literally every other advanced country does universal healthcare. Look at such places as Taiwan, Switzerland, and Israel.

In any comparison, the US system is astoundingly poorly designed. Three key parts of that are the link between employment and insurance, the way that insurance companies are unrestrained, and the way that the US does NOT regulate pharmaceutical prices.

Go find a non Heritage foundation health economist who defends the US system.