China's industrial policy has an unprofitability problem

China is paying its national champions to fight each other to the death.

Analyzing American economic policy isn’t that interesting these days, except perhaps as a grim spectacle. So I’ve been thinking a little about Chinese economic policy. China’s leaders leave much to be desired, but to their credit, they still think economic policy is about strengthening their nation, enriching their people, and improving their technology, instead of pursuing domestic culture wars by other means.

Anyway, China has a lot of policy initiatives right now — cleaning up the fallout from the real estate bust, retaliating against America’s tariffs, improving their health care system, and so on. But their most important policy — and the one everyone talks about here in the U.S. — is their big industrial policy push.

If you want to understand Chinese industrial policy, I recommend starting with Barry Naughton’s free book, The Rise of China’s Industrial Policy: 1978 to 2020. The basic story is that until the mid to late 2000s, China didn’t really have a national industrial policy as such. It had a bunch of local governments trying to build up specific industries, usually by attracting investment from multinational companies. And it had a central government that tried to make it easy for local governments to do that, using macro policies like making sure coal was cheap, holding down the value of the Chinese currency in order to stimulate exports, and so on.

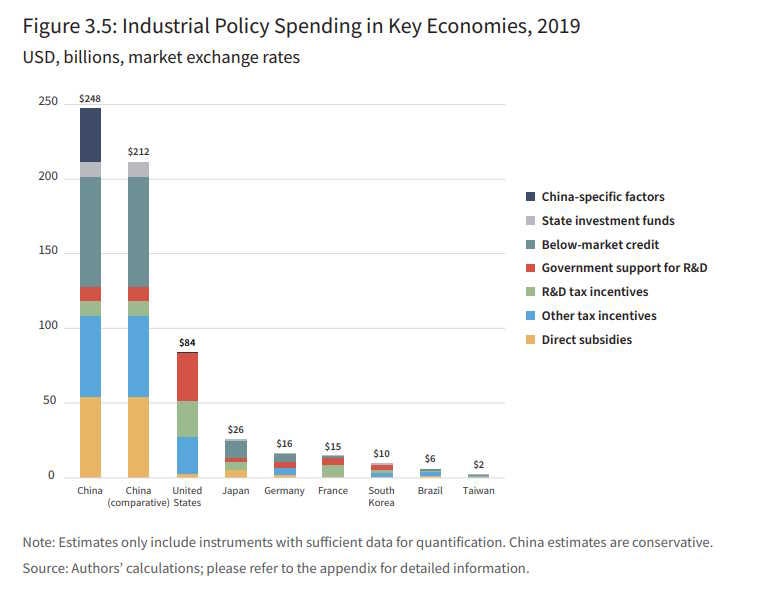

But it was not until the end of Hu Jintao’s term in office — and really, not until Xi Jinping came to power — that China developed a national industrial policy, in which the government tries to promote specific industries using tools like subsidies and cheap bank loans. If you want a good primer on just how big those loans and subsidies are, and which industries they’re going to, I recommend CSIS’ 2022 report, “Red Ink: Estimating Chinese Industrial Policy Spending in Comparative Perspective”. It’s a lot. Here are the authors’ estimates from 2019:

In some respects, this policy was successful. For example, it moved China up the value chain — instead of doing simple low-value assembly for foreign manufacturers as in the 2000s, China in the 2010s learned to make many of the higher-value components that go into things like computers, phones, and cars, as well as many of the tools that create those goods. This had the added security benefit of making China less dependent on foreign rivals for key manufacturing inputs.

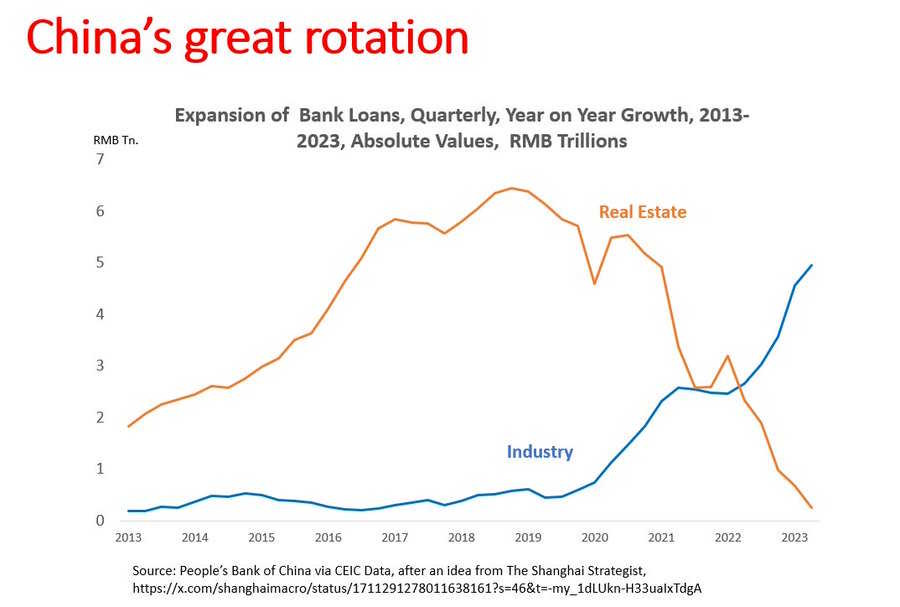

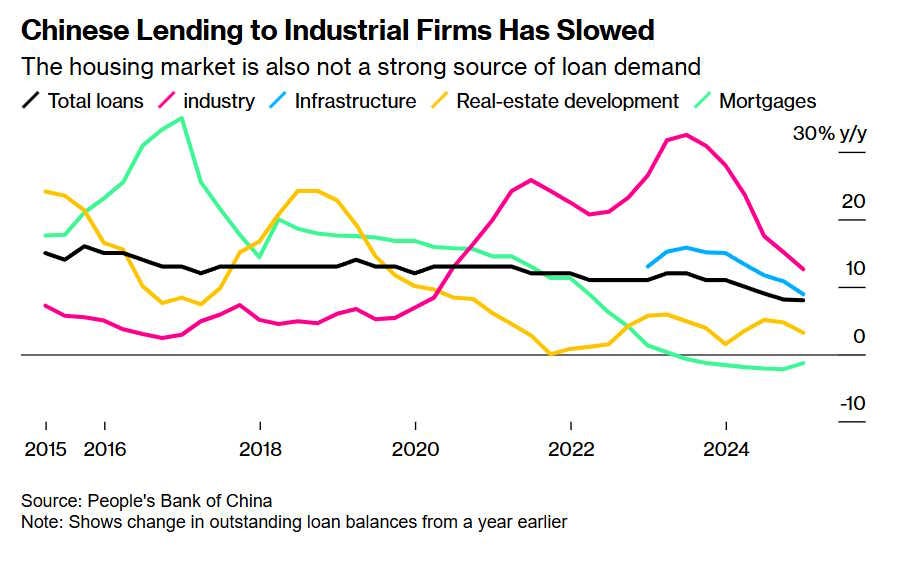

China has doubled down on its centralized, big-spending industrial policy since then. In 2021-22, China suffered a huge real estate bust, crippling a sector that had accounted for almost one third of the country’s GDP. China’s leaders responded by doubling down on manufacturing, encouraging banks — essentially all of which are either state-owned or state-controlled — to shift their lending from real estate to industry. In 2023, you saw charts like this:

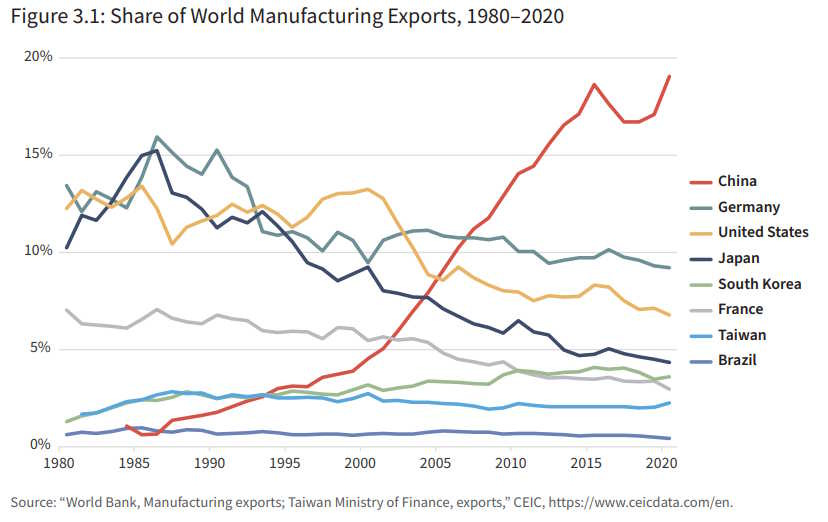

Along with this industrial policy, you saw a massive surge of Chinese manufactured exports flowing out to the rest of the world. The most recent export surge has been labeled the “Second China Shock”, but in fact the trend was already headed in that direction well before the pandemic:

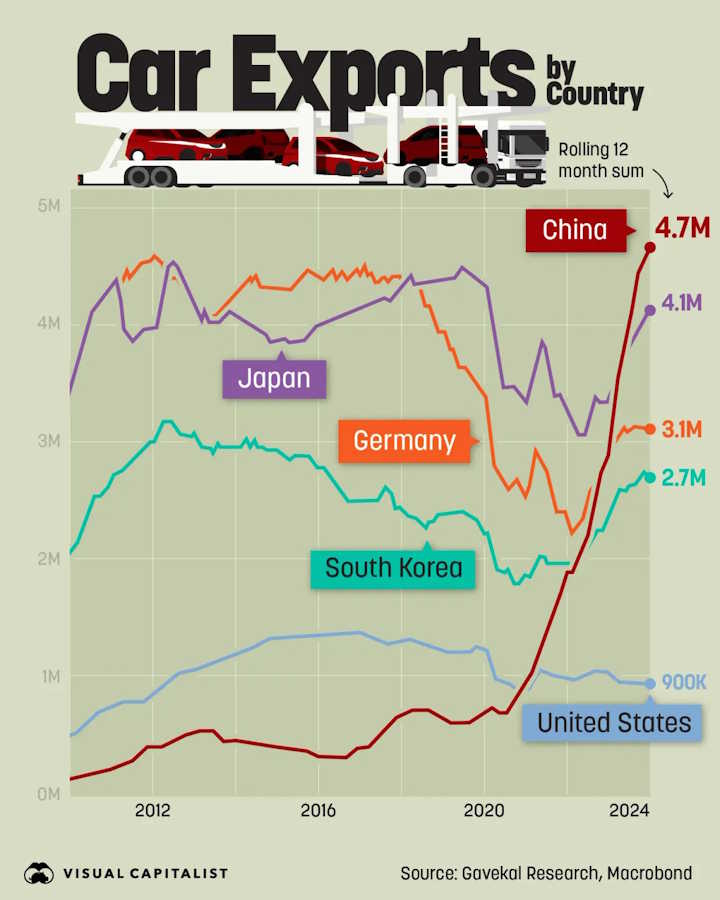

China’s competitive success in manufacturing industry after industry has been nothing short of spectacular. In just a couple of years, China went from a footnote in the global car industry to the world’s leading auto exporter:

Obviously, this export surge is the most important way that people in countries like the U.S. experience the results of China’s industrial policy. So most commentary on the policy has focused on exports, trade balances, and so on.

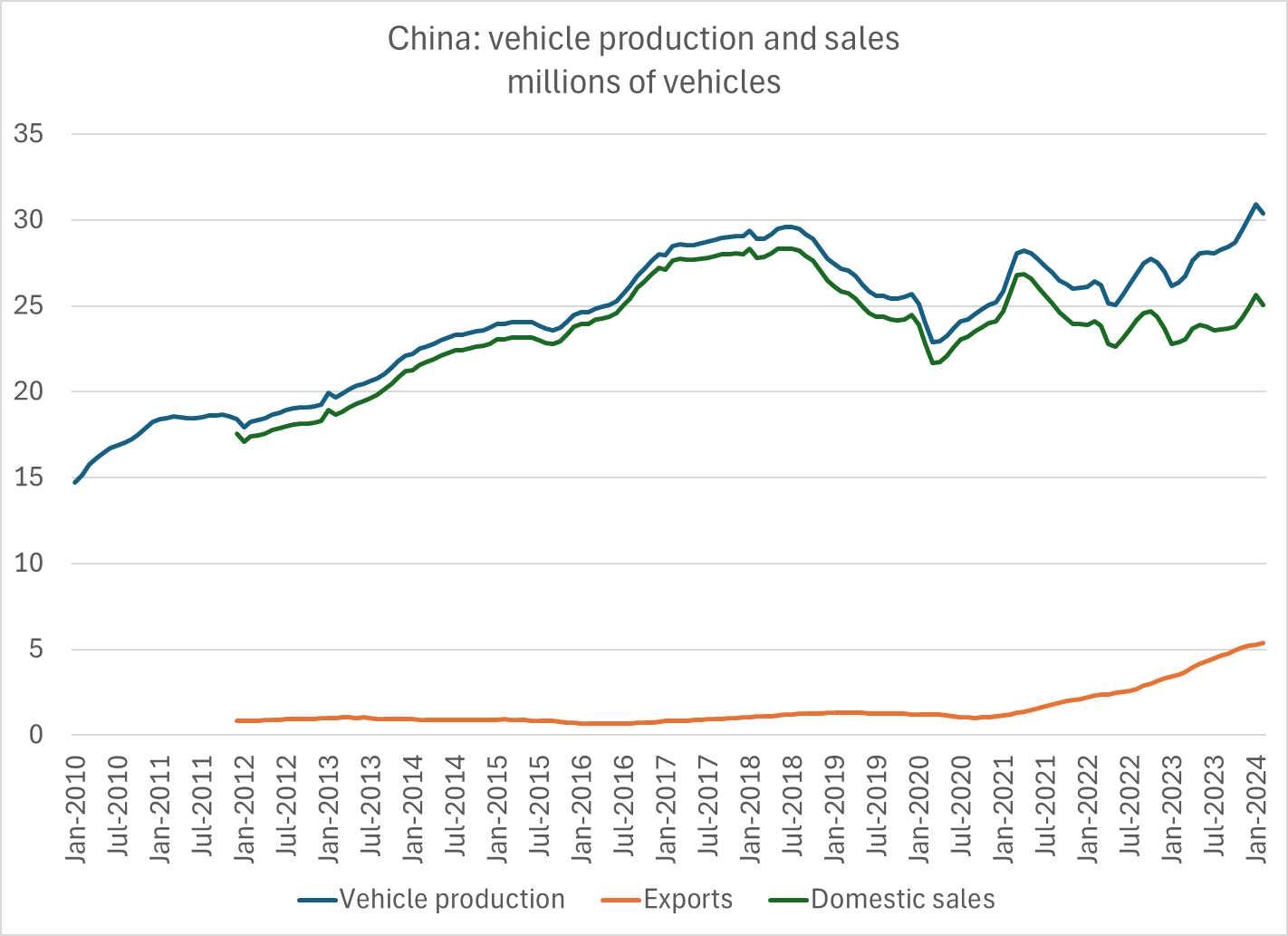

But it’s important to remember that most of what China is producing in this epic manufacturing surge is not being exported. For example, take cars. Even though China is now the world’s top car exporter, most of the cars it makes are sold within China:

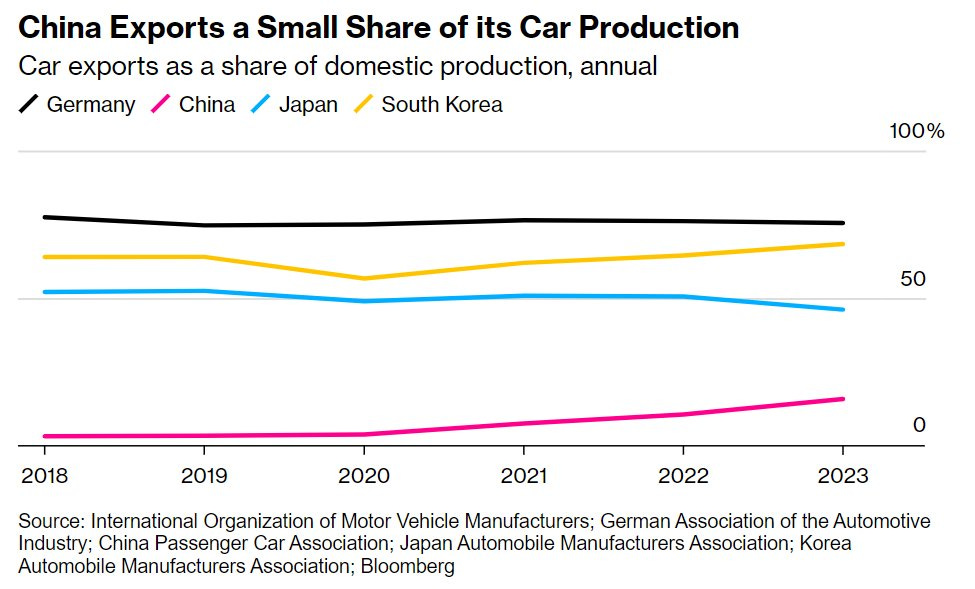

China’s auto industry is actually unusually domestically focused, compared to other auto powerhouses like Germany, South Korea, and Japan:

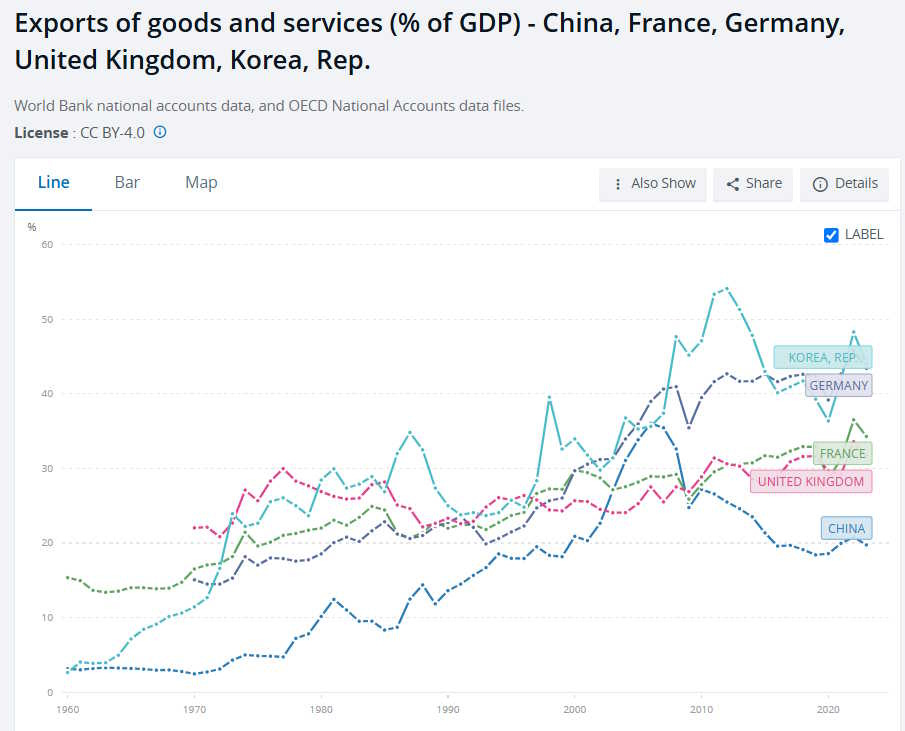

In fact, this pattern holds across the whole economy. For an industrialized country, China is unusually insular — its exports as a percent of its GDP are higher than the U.S., but much lower than France, the UK, Germany, or South Korea:

Most of China’s enormous manufacturing subsidies are not actually for export manufacturing; they’re for domestic manufacturing. The rest of the world is just getting a little bit of spillover from whatever Chinese companies can’t manage to sell domestically — except for a country as huge as China, a “little spillover” can seem like a massive flood to everyone else.

And here lies the rub. Essentially, China is huge and most of its trading partners are pretty small. There’s a limited amount of Chinese cars, semiconductors, electronics, robots, machine tools, ships, solar panels, and batteries they can buy. And on top of that, some of China’s biggest trading partners are levying tariffs against it.

For most Chinese manufacturers, export markets are simply not going to replace the domestic market. And this means that Chinese manufacturers will be forced to compete against each other for a domestic market whose size is relatively fixed, at least in the short term. That competition will eat away at their profit margins.

In fact, this is already happening. Vicious price wars have broken out in the Chinese auto industry, and even the country’s top carmakers are under extreme pressure:

Chinese carmakers’ price war is putting the industry’s balance sheet under strain…Current liabilities exceeded current assets at more than a third of publicly listed car manufacturers at the end of last year…China’s leading carmakers are being forced to…fight for market share amid heavy [price] discounting…

The dominant electric-vehicle maker BYD is deepest in negative territory with its working capital, followed by rivals Geely, Nio, Seres and state-backed BAIC and JAC, while the total net current assets of 16 major listed Chinese carmakers [saw] a 62 per cent decline from…the first half of 2021…

“Given the current downward trend, China’s auto industry is expected to enter an industry-wide elimination phase . . . in 2026 at the latest,” [an analyst] warned. “During the process, some companies will die of liquidity crises.”…

BYD recently came under pressure to defend its financial numbers and business practices after Wei Jianjun, chair of rival Great Wall Motor, called for a comprehensive audit of all major domestic carmakers…“An Evergrande exists in [China’s] auto sector at the moment — it just hasn’t blown up,” he told local media, raising the spectre of the industry following the property sector into a spiralling debt crisis.

How can these mighty world-conquering automakers be skating on the edge of bankruptcy when the government is pouring so many subsidies and cheap loans into the auto industry? The answer is simple: China’s government is paying its car companies to compete each other to death.

The Chinese government pays a ton of different car companies to make more cars. Chinese banks, at the government’s behest, give cheap loans to a bunch of different car companies to make more cars. So they all make more cars — more than Chinese consumers want to buy. So they try to sell some of the extra cars overseas, but foreigners only buy a modest amount of them. Now what? Unsold cars pile up, prices are cut and cut again, and all the car companies — even the best ones, like BYD — see their profit margins fall and fall.

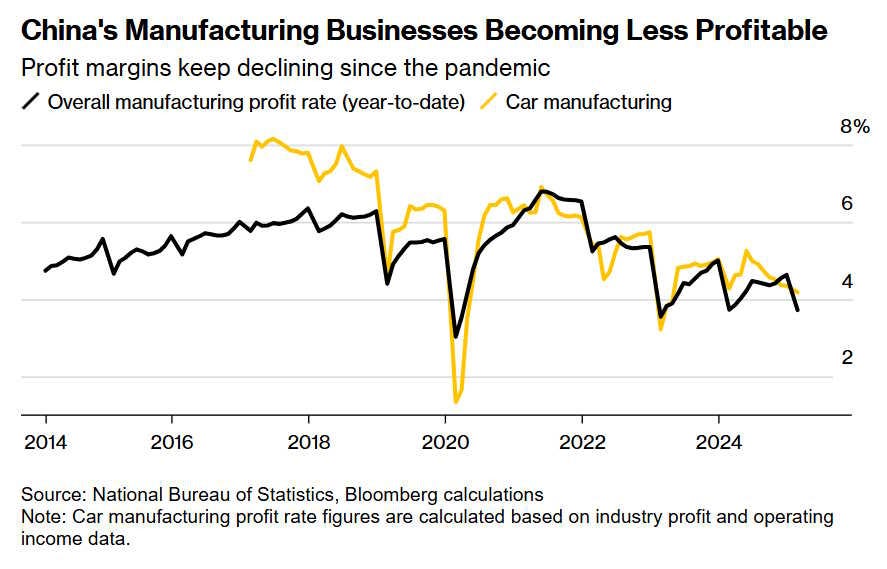

It’s not just autos, either — similar things are happening in solar, steel, and a bunch of other industries. Manufacturing profit margins are plunging across China’s entire economy:

A Chinese buzzword for this sort of excessive competition is “involution”.

Why is this bad, though? Who cares about profit, anyway? After all, China’s workers are getting jobs, and China’s consumers are getting a ton of cheap cars and other manufactured stuff. So what if rich BYD shareholders and corporate executives take a loss?

Well, in fact there are several problems. The first is macroeconomic. Price wars across much of the economy create deflation. In fact, China is already experiencing deflation:

China’s consumer prices fell for a fourth consecutive month in May…with price wars in the auto sector adding to downward pressure…The consumer price index fell 0.1% from a year earlier…CPI slipped into negative territory in February, falling 0.7% from a year ago, and has continued to post year-on-year declines of 0.1% in March, April, and now May…Separately, deflation in the country’s factory-gate or producer prices deepened, falling 3.3% from a year earlier in May[.]

A lot of this is probably due to weak demand from the ongoing real estate bust, but price wars prompted by industrial policy will make it worse.

Deflation will exacerbate the lingering problems from the real estate implosion. Debts are in nominal terms, meaning that when prices go down, those debts become harder to service. More of the debts go bad, and banks get weaker — all those bad loans on their books make them less willing to make new loans. Consumer debts get more onerous too, making consumers less willing to spend (and consumers, unlike banks, are not government-controlled). This effect is called debt deflation.

On top of that, a massive wave of bankruptcies could cause a second bad-debt crisis on top of the one that’s already happening from real estate. Wei Jianjun of Great Wall Motor has been warning of exactly this happening. In fact, we can already see Chinese banks beginning to slow the torrid pace of industrial loans they were dishing out a couple of years ago:

All of this could extend China’s growth slowdown for years.

There are also microeconomic dangers from overcompetition. Competition could spur Chinese companies to just innovate harder. But if China’s top manufacturers are constantly skating on the edge of bankruptcy, that means they’ll have fewer resources to invest in long-term projects like technological innovation and new business models. Basically, prices are signals about what to build, and China’s industrial policies are sending strong signals of “build more stuff today” instead of “build better stuff tomorrow”.

There’s also the danger that China’s government won’t allow the price wars to end. Ideally, you’d want these price wars to be temporary; eventually, you’d want weak producers to fail, allowing top producers to increase their profitability. This good outcome relies on the government eventually cutting subsidies and letting bad companies die.

But letting bad companies die means a bunch of people get laid off. Bloomberg recently had a good report about the political pressures on the Chinese government to keep the subsidies flowing:

Local leaders laden in debt are rolling out tax breaks and subsidies for companies, in a bid to stave off the double whammy of job and revenue losses…For China’s top leaders, employment is an even more politically sensitive issue than economic growth, according to Neil Thomas, a fellow for Chinese politics at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis…Already there are signs the weakening labor market is becoming a touchy subject: One of China’s largest online recruitment platforms Zhaopin Ltd. this year quietly stopped providing wage data it’s compiled for at least a decade.

Already, Bloomberg reports that economic protests are proliferating across the country; with the real estate crisis ongoing, the government will be under even more political pressure to keep manufacturing employment strong. This could mean keeping crappy companies on life support. These so-called “zombie” companies, kept alive only by a neverending flood of cheap credit, were a big part of why Japan’s economy slowed down so much in the 1990s.

So this is the scenario where China’s industrial policy ends up backfiring. Subsidies and cheap bank loans dished out to high-quality and low-quality companies alike could flood the market with undesired product, spurring vicious cutthroat price wars, destroying profit margins, exacerbating deflation, and generally making the macroeconomic situation worse. And then China’s government could double down by trying to protect employment, by never halting subsidies for companies that fail.

Usually, when we think of the costs of industrial policy, the main thing we think about is waste — and there is certainly plenty of waste in China’s current approach. But China’s experience is illuminating a second problem with industrial policy — the risk of vicious price wars and deflation, due to the subsidization of too many competing companies.

It continues to be ironic that Communist Party rule in China enables them to be a kind of archetype of social Darwinist capitalism in economic policy.

This reminds me of shared cycle business in China - where the market got totally saturated while the companies never made profit and all of a sudden companies after companies go bankrupt.

In fact, I remember reading Minetoshi Yasuda, a Japanese journalist specializing in China, described that Chinese companies tend to care way more about investment flows (subsidies or stock price) than the profit itself.

He also mentioned that Chinese companies tend to follow herd mentality to join trending industries, resulting in finding themselves in the red ocean rather than try to differentiate themselves to find niche. I feel like this is an apt observation