Book Review: "Doughnut Economics"

In which Kate Raworth summarizes many leftish criticisms of economics.

“I took my money/ And bought a donut/ Hole the size of this entire world” — Sleater-Kinney

Here’s a very short, oversimplified history of modern economics. In the 1960s and 1970s, a particular way of thinking about economics crystallized in academic departments, and basically took over the top journals. It was very math-heavy, and it modeled the economy as the sum of a bunch of rational human agents buying and selling things in a market.

The people who invented these methods (Paul Samuelson, Ken Arrow, etc.) were not very libertarian at all. But in the 70s and 80s a bunch of conservative-leaning economists used the models to claim that free markets were great. The models turned out to be pretty useful for saying “free markets are great”, simply because math is hard — it’s a lot easier to mathematically model a simple, well-functioning market than it is to model a complex world where markets are only part of the story, and where markets themselves have lots of pieces that break down and don’t work.1 So the intellectual hegemony of this type of mathematical model sort of dovetailed with the rise of libertarian ideology, neoliberal policy, and so on.

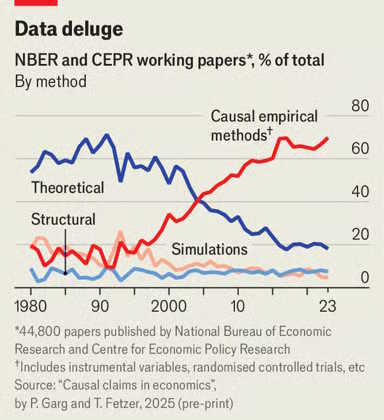

A lot of people sensed that something was amiss, and set out to find problems with the story that the libertarian economists were telling. These generally fell into two camps. First, there were people who worked within the 1970s-style mathematical econ framework, stayed in academia, and tried to change the dominant ideas from inside the system. They came up with things like public goods models, behavioral economics, incomplete market macroeconomics, and various game-theory models in which markets fail. When the computer revolution made it a lot easier to do statistical analysis, they started to do a lot more empirical work, and a lot less theory:

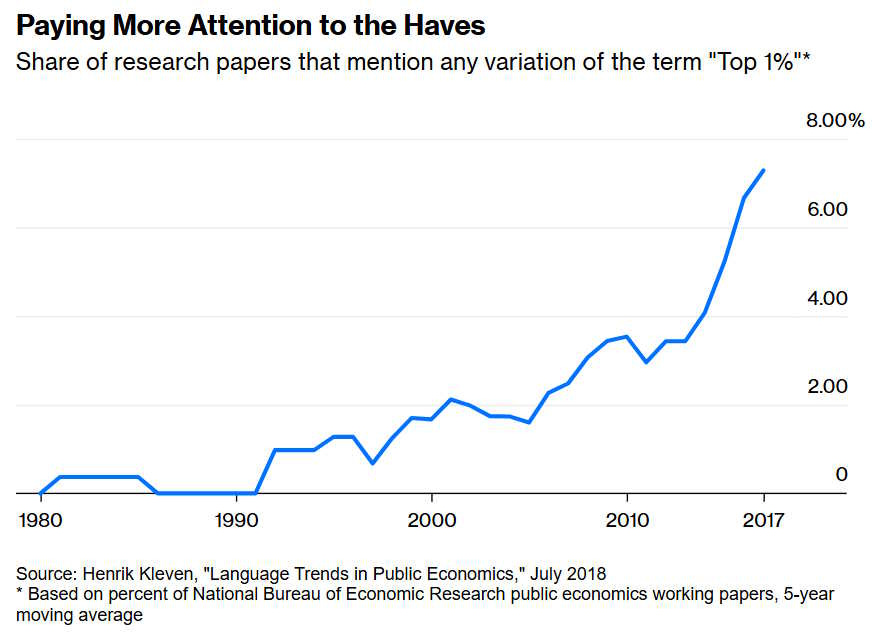

These changes also moved the field more to the left politically. To take just one small example, you can see a lot more economists writing about inequality in recent years:

But there was also a second group of people who fought against the intellectual hegemony of the libertarian economists. They rejected the 1970s-style math models that the profession insisted on using — either because they didn’t think it made sense to model an economy using that sort of math, or because they couldn’t personally handle the math — and instead sought insight in alternative disciplines like ecology, sociology, history, etc. These folks — who often called themselves “heterodox” — tended to lean even more strongly to the left, and often unabashedly mixed their methodological critiques with socialist or other leftist politics.

The heterodox folks had a problem. They had a huge grab-bag of critiques, but nothing really tied those critiques together. There was no new paradigm — no simple new way of thinking about economics. Marxism had provided that idea for much of the 20th century, but Marxism was defunct. That lack of a unifying framework weakened the heterodox cause, because it still seemed to leave 1970s-style free-market economics as the “base case” — the simple core idea that people kept returning to. It’s relatively easy to explain to a bright 21-year-old how supply and demand work in a simple competitive “Econ 101” model; it’s a lot harder to explain two dozen ways in which that model fails.

So for years, the heterodox people have been writing versions of the same old list of critiques, while searching for someone who could synthesize this list into a simple new paradigm.1 This call was answered by Kate Raworth, a British researcher who has worked for international development agencies and for Oxfam before getting various posts at European universities. In 2017, Raworth wrote a book called Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, which promised to replace the old neoclassical economic paradigm with something newer and better.

Although this book is now eight years old, a number of friends have recently asked me to read and review it. So here is that review.

Doughnut Economics is based around an important insight: Diagrams are powerful marketing tools. Raworth, seeing how the basic supply-and-demand graph and the circular flow diagram had helped popularize neoclassical economics2, set out to create a diagram that was as simple and as powerful as those. She writes:

[T]his book aims to reveal the power of visual framing and use it to transform twenty-first century economic thinking…Visual frames, it gradually dawned on me, matter just as much as verbal ones…[N]ow is the time to uncover the economic graffiti that lingers in all of our minds and, if you don’t like what you find, scrub it out; or better still, paint it over with new images that far better serve our needs and times…The diagrams in this book aim to summarise that leap from old to new economic thinking.

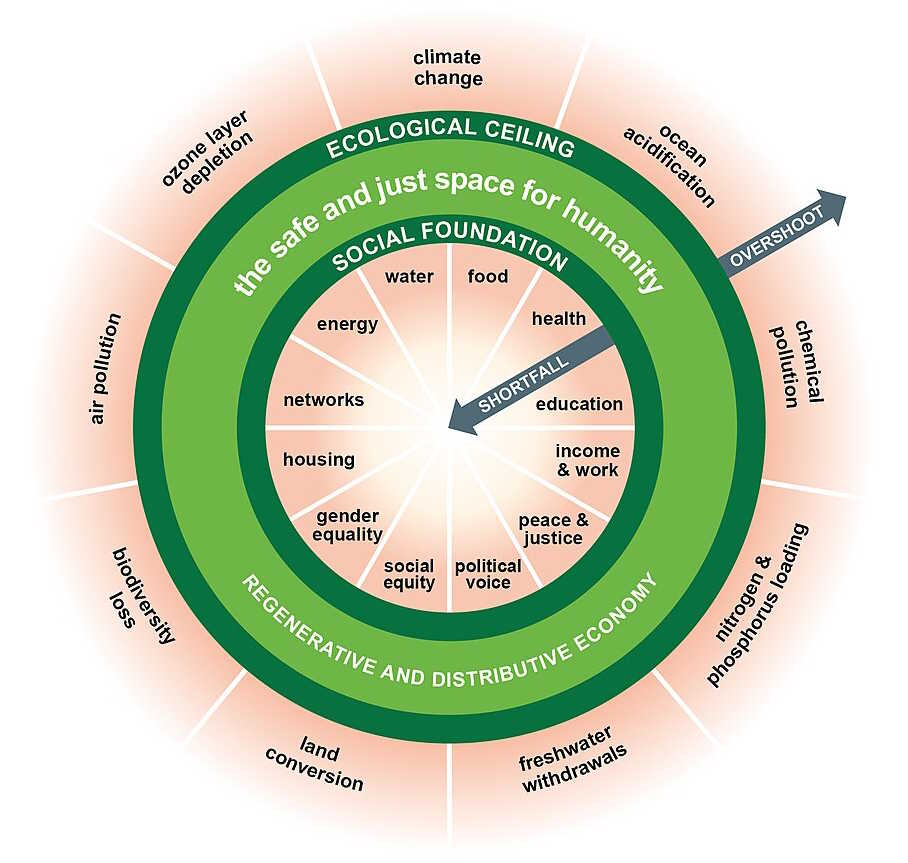

Most importantly, Raworth came up with something she calls the Doughnut — a set of concentric circles that illustrates the tradeoff between the environment and human prosperity:

Going towards the center of this diagram represents more human poverty; when you go inward beyond the dark green band, you deprive and impoverish humans. Going outward represents more human prosperity; when you go out beyond the dark green band, you despoil the environment.

In fact, this tradeoff is very real. Natural resources are plentiful, but not infinite; produce too much in the present, and you’ll leave little for future humans (and other animals) to enjoy. Furthermore, plenty of industrial activity creates negative externalities, like when burning fossil fuels emits carbon and disrupts the climate. So the Doughnut depicts something that we really do need to think about.

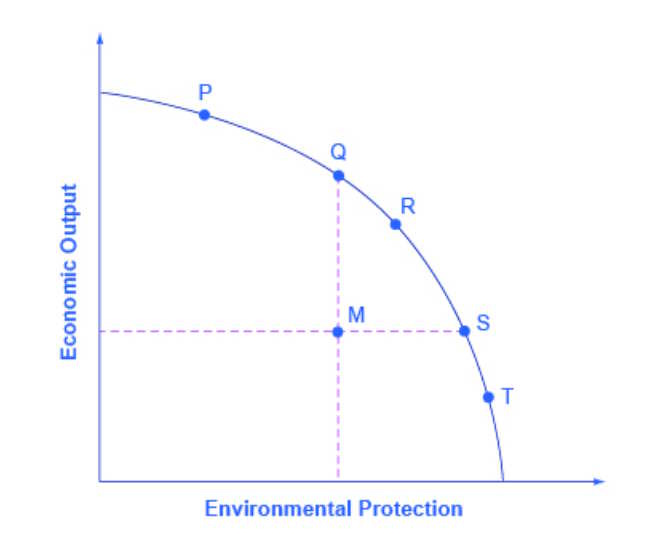

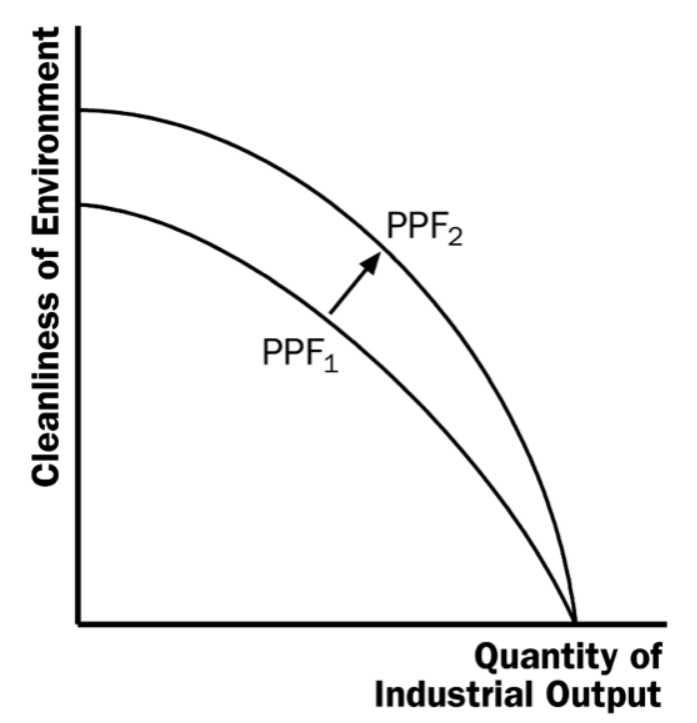

In fact, mainstream economics already has a simple way of depicting this in a memorable picture — a production possibilities frontier. A PPF illustrates society’s tradeoff between two things. You can draw a PPF that illustrates the tradeoff between production and the environment; in fact, introductory econ courses do this all the time:

You could label this diagram with every single one of the items that Raworth puts in her Doughnut — food, housing, biodiversity, climate change, and all the rest. You could label one part of the curve “the safe and just space for humanity”. It would be easier to read. Or, alternatively, you could draw a PPF for each type of industrial activity, or each type of environmental degradation. But Raworth is interested in intellectual revolution, not evolution; the humble PPF is disqualified because of its association with the existing mainstream, and so she never even mentions it in her book.

Raworth presents the Doughnut as an alternative to the idea of infinite exponential economic growth, which she sees mainstream economics as supporting. I suspect that this explains the book’s popularity. In recent years, the idea of degrowth has gained popularity, especially in the UK and North Europe. But on some level, people realize that degrowth is very bad for developing countries, since economic growth — not foreign aid or remittances — is the only thing that has ever been able to durably raise people out of desperate poverty. So even lefty intellectuals in the UK or Sweden realize that the idea of degrowth, applied across the world, would be a monstrous crime against humanity.

Raworth is sympathetic to the degrowthers, but she is not one of them. She spends a lot of time discussing the limits of GDP as an economic goal, talking about the tradeoff between growth and the environment, and arguing that exponential growth has to end eventually. But she also recognizes the importance of material prosperity for people in poor countries:

In many low-income but high-growth countries…when that growth leads to investments in public services and infrastructure, its benefits to society are extremely clear. Across low- and middle-income countries…a higher GDP tends to go hand-in-hand with greatly increased life expectancy…far fewer children dying before the age of five, and many more children going to school. Given that 80 percent of the world’s population live in such countries…significant GDP growth is very much needed, and it is very likely coming. With sufficient international support, these countries can seize the opportunity to leapfrog the wasteful and polluting technologies of the past.

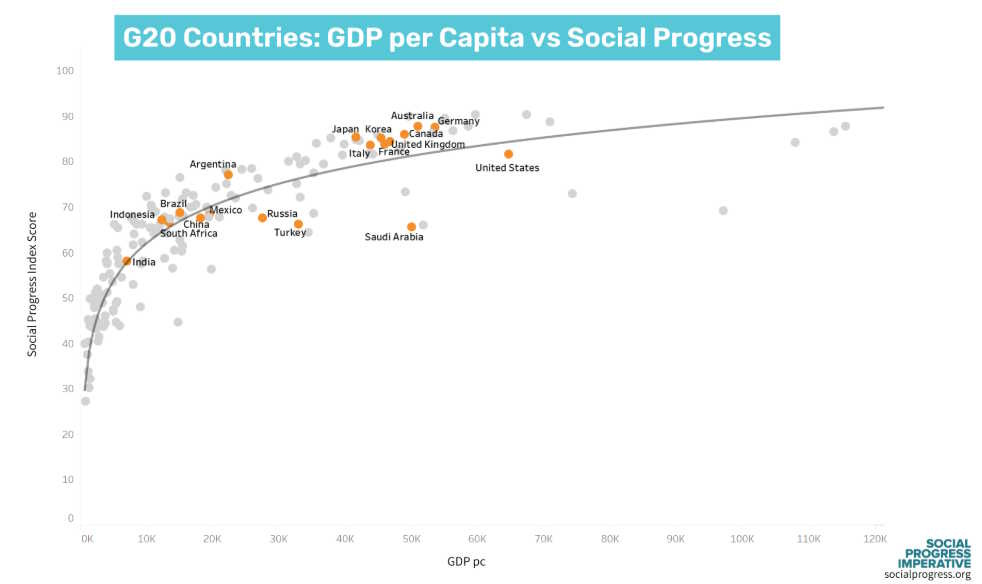

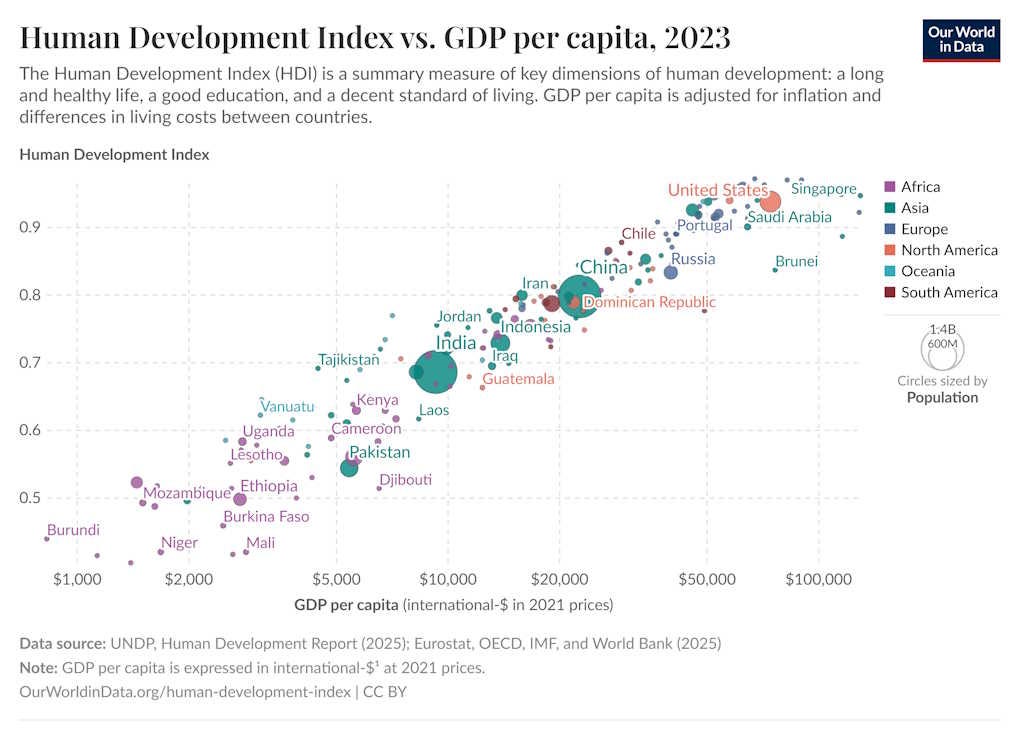

This is my view as well, and it’s the only reasonable conclusion for anyone who has worked in international development (as Raworth has). A lot of people who are dissatisfied with GDP as a measure of human flourishing have spent a lot of time creating alternative measures, like the Human Development Index. These always end up being very strongly correlated with GDP. For example, here’s HDI:

It looks like the correlation flattens out a bit at the top, but that could just be because the index can’t go higher than 100; if you let it go higher, the correlation might persist even at high levels of income.

They’re all like this. Googling around, I found something called the Social Progress Imperative, which makes some index of “social progress”. I’ve never seen this index before, and I didn’t even need to look3 to know at the country level it’s going to be strongly correlated with GDP:

As with HDI, the apparent flattening at the top of the curve might just be due to the fact that the index is capped at 100, and rich countries tend to be placed near 100.

Now, these are just correlations. There’s no guarantee that making a country richer will solve all its social problems. Americans are way richer than Europeans, but this hasn’t yet solved our crime problem, our mental health problems, our drug problems, and so on. We need more than GDP growth to make a good society. Yet at the same time, GDP continues to be a great rough-and-ready benchmark for how well a society is doing. And as Raworth wisely points out, for poor countries, material deprivation is the main problem, and that does get solved by economic growth.

So Raworth strikes a balance between the trendy lefty idea of degrowth and the obvious need for poor-country development. She recognizes that growth is important for poor countries, but that it isn’t the be-all and end-all of a good society. And she recognizes that there’s a fundamental tradeoff between economic growth and the environment. So she recommends that rich societies focus less on growth and more on fixing their other problems.

So far, so good. That is a reasonable thing to argue. There are reasons to argue against it, including:

Rich-country growth drives technological progress more than poor-country growth does, and technological progress is often necessary both to save the environment and to improve society.

Rich-country growth creates demand for poor-country exports, and leads to investment in poor countries, thus helping them grow.

If rich democracies don’t grow economically, they may be conquered by countries like Russia that don’t care about the environment or about social progress.

Raworth doesn’t consider these benefits of rich-country growth. But if she had stuck to the core message of environmental tradeoffs and the inadequacy of GDP growth, it would have made for a very good, tight, focused book.

But Doughnut Economics is not a tight, focused book. Instead of delivering a simple, powerful message, Raworth tries to intellectually overthrow the entire edifice of modern economics. And in this task, she fails.

First of all, Raworth doesn’t seem to fully understand the value of the things she criticizes. Of course she’s right that simple pictures like supply-and-demand graphs make great marketing devices, but they’re also much more than that.

For example, you can also use those pictures to do thought experiments. If you model the market for oranges with a supply-and-demand graph, you can think about the effects of a hurricane in Florida as a negative supply shock — you can shift the supply curve to the left, and the graph will tell you that A) fewer oranges get sold, and B) the price of oranges goes up.

In principle, you could do that with Raworth’s Doughnut this way, too. For example, consider an advance in green technology — suppose someone invents a way to make cheap zero-carbon cement. You could model this with the environmental PPF that I illustrated above. This technology loosens the tradeoff between growth and the environment — it shifts the PPF outward, allowing us to have more human wealth for the same amount of environmental degradation:

You could just as easily draw this as an expansion of Raworth’s donut. The outward ring of the donut would expand, and the “safe and just space” for humanity would become more capacious, illustrating the benefits of green technology.

But although she could, Raworth never actually uses her Doughnut like this. Instead of a predictive analytical tool, she simply uses it as a laundry list of every possible good thing that she would like humanity to have. It’s less of a doughnut than an Everything Bagel.

Indeed, Raworth generally rejects the notion of economics as a predictive, analytical tool at all. Like many heterodox types, she argues that economics should be not a positive but a normative discipline — a branch of political philosophy focused on telling us what goals we ought to have for our society, rather than an analytical tool for predicting how economies work. She writes:

In the twentieth century, economics lost the desire to articulate its goals…[John Stuart] Mill began a trend that others would further: turning attention away from naming the economy’s goals and towards discovering its apparent laws…[T]he discussion of the economy’s goals simply disappeared from view. Some influential economists, led by Milton Friedman and the Chicago School, claimed this was an important step forwards, a demonstration that economics had become a value-free zone, shaking off any normative claims of what ought to be and emerging at last as a ‘positive’ science focused on describing simply what is. But this has created a vacuum of goals and values[.]

But in her desire to turn economics back into a philosophy of values, Raworth essentially abandons its use as a tool of prediction and analysis. For prediction and analysis, she turns to other disciplines — climate science, ecology, and “complexity science”. But there are many questions that these disciplines are not set up to answer — and which modern economics can answer.

For example, Raworth would probably agree that well-functioning public transit is an important function of government and society. If the government is considering building a new train extension, it’s important to be able to predict how many people will use it; otherwise, you may end up wasting Earth’s scarce resources. Ecology may give you metaphors to think about humans riding trains, and complexity science may simply tell you that a system of transit is complex. That’s not very helpful.

But with economics, you can actually estimate a demand curve for transit ridership, and use that estimate to make accurate predictions about how many people will ride the train, as Dan McFadden won a Nobel prize for successfully doing in the 1970s. You can’t do that with a Doughnut!

In fact, there are plenty of other “positive” questions that modern economics is set up to answer. The electromagnetic frequency spectrum is a commons that must be allocated in order for people to hear each other over a cell phone network; economics can predict the results of various spectrum auction mechanisms. Allocating kidney transplants is important in order to save lives; economic theory can successfully tell you how to get the most kidneys to the most recipients, thus saving the most lives. There are many other examples.

Raworth doesn’t seem very aware of these predictive successes of modern economic theory. Nor does she seem to have a firm idea of what would replace them if the theories of supply and demand, equilibrium, etc. were thrown out the window.

Part of the problem is that Raworth’s understanding of the mainstream economic paradigm she wants to overthrow seems limited. For example, in Chapter 5, she argues for keeping interest rates low by making loans with state-owned banks:

State-owned banks could…use money from the central bank to channel substantial low- or zero-interest loans into investments for long-term transformation, such as affordable and carbon-neutral housing and public transport. It…would shift power away from what Keynes called ‘the rentier…the functionless investor.’

But in the very next paragraph, she denounces quantitative easing, which was a central bank program to keep interest rates low during the Great Recession:

[C]ommercial banks used that money [from QE] to rebuild their balance sheets instead, buying speculative financial assets such as commodities and shares. As a result, the price of commodities such as grain and metals rose, along with the price of fixed assets such as land and housing, but new investment in productive businesses didn’t.

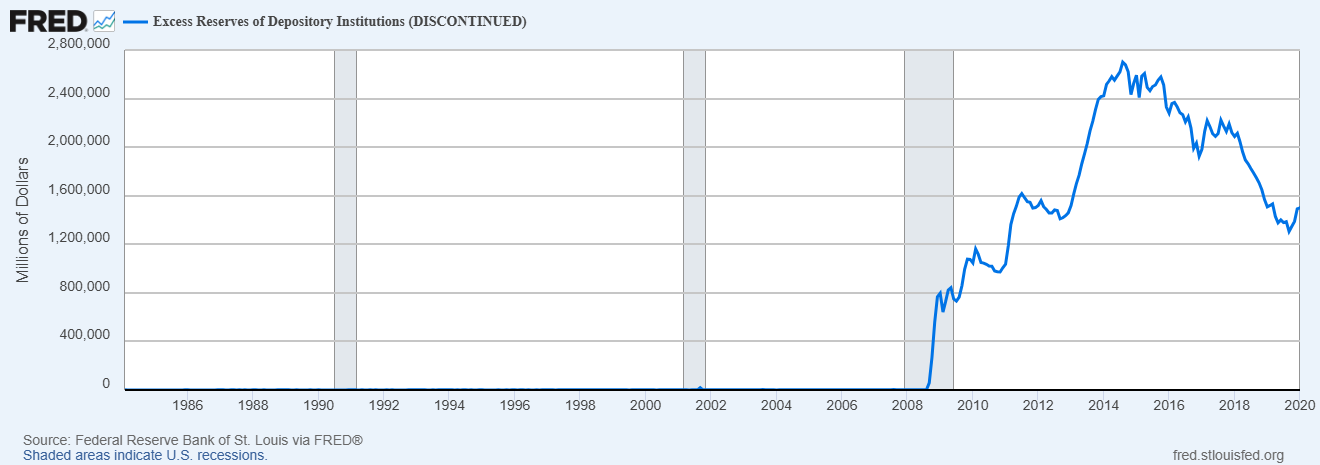

First of all, this misunderstands what it means for a bank to rebuild its balance sheet. It doesn’t mean for a bank to buy stocks and houses and commodities. It means for a bank to hold cash. Banks took the money from QE and essentially stuck it in a vault, holding what’s known as “excess reserves”:

Raworth also seems to misunderstand how asset prices work. When interest rates go down, the time value of money goes down, which raises the price of assets like stocks and houses. When Keynes talked about the “euthanasia of the rentier”, he meant that investors wouldn’t be able to earn a bunch of free money from keeping their money in bank accounts or government bonds; he didn’t mean that the rate of return on risky assets like stocks and houses would fall. In fact, rate cuts give a permanent boost to the price of those assets, creating a windfall for the rich people who own them.

Raworth doesn’t appear to understand this at all. She also advocates for central banks to print money and give it directly to people — a proposal she calls “People’s QE”, though the more common term is “helicopter money”. But beyond whatever inflation issues this would cause, it would also raise asset prices, because people would use some of that money to buy houses and stocks. That would give a windfall to asset owners, just like regular QE did.

Later, in Chapter 7, Raworth argues that the environment would benefit if cash lost value over time — in other words, if the economy had negative nominal interest rates. She writes:

What kind of currency, then, could be aligned with the living world so that it promoted regenerative investments rather than pursuing endless accumulation? One possibility is a…small fee for holding money, so that it tends to lose value the longer it is held…Today the…effect could be achieved…by electronic currency that incurred a charge for being held over time, so curtailing use of money as a store of ever-accumulating value…It would transform the landscape of financial expectations: in essence, the search for gain would be replaced by the search to maintain value.

This gets the effect of depreciating currency exactly wrong. If your cash is losing value, what do you do? You go out and spend it as quickly as you can!4 In fact, my PhD advisor, Miles Kimball, has long advocated for depreciating electronic money as a way to stimulate consumers to spend more! Raworth is proposing something that she thinks would limit consumption, but which would actually supercharge it.

The whole book is littered with these misconceptions. This is sadly typical of heterodox econ critics, who are so sure that they want to throw out all of modern economics that they often can’t be bothered to understand what they’re trying to overthrow. If you’ve decided that a bag contains nothing but trash, why look inside it before you toss it in the dumpster? And yet for all its flaws and limitations, modern economics has succeeded in uncovering some real insights about how the economy works, and a heterodox takeover would throw these out.

Another big problem with Doughnut Economics is its epistemology. When facts seem to support Raworth’s desired conclusions, she doesn’t question them; when they seem to run counter to her ideas, she often dismisses them. For example, in Chapter 6, Raworth discusses the idea that past a certain point, as countries get richer, they pollute less.5 She cautions us not to believe that this correlation represents real causation:

Grossman and Kruger…pointed out that an observed correlation between economic growth and falling pollution didn’t demonstrated that growth itself caused the clean-up.

But then on the very next page, she discusses the correlation between economic equality and environmental quality, and interprets it as causation:

Mariano Torras…and James K. Boyce…found that environmental quality is higher where income is more equitably distributed, where more people are literate, and where civil and political rights are better respected. It’s people power, not economic growth per se, that protects local air and water quality.

And yet although Torras and Boyce (1998) propose a causal mechanism from political power to environmental quality, they don’t have a way of testing that linkage; it remains a hypothesis.

And earlier, in Chapter 5, Raworth writes:

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett…discovered that it is national inequality, not national wealth, that most influences nations’ social welfare. More unequal countries, they found, tend to have more teenage pregnancy, mental illness, drug use, obesity, prisoners, school dropouts and community breakdown, along with lower life expectancy, lower status for women and lower levels of trust…More equal societies, be they rich or poor, turn out to be healthier and happier.

These are all just observed correlations, but Raworth interprets them all as causation without questioning whether other factors might be at work.

The issue clearly isn’t that Raworth fails to understand the difference between correlation and causation; she obviously does, because she uses it to question results she doesn’t like, like the finding that higher incomes are correlated with less pollution of certain types.6 But she fails to apply this stringent, critical intellectual standard to correlations between economic equality and various positive outcomes. Causation for me, mere correlation for thee.

Other times, Raworth simply seems uninformed. For example, in Chapter 7 she says that Canada has “failed to achieve any absolute decoupling” between emissions and growth. That’s just wrong; in 2017, when Doughnut Economics went to press, Canada’s emissions were down from their 2007 peak, while GDP was up by 17%. The absolute decoupling was even stronger if measured in consumption-based terms (i.e., adjusting for offshoring of emissions), and in per capita terms.

Later in the chapter, Raworth cites the Easterlin Paradox as evidence that higher incomes don’t make countries happier. But while income certainly has diminishing returns in terms of happiness, the Easterlin Paradox itself was debunked with better data long before Doughnut Economics was published; as far as we can tell, the correlation between income and happiness never breaks down as countries get richer.

Raworth is generally so eager to overthrow modern economics that she will turn to any and every ally that seems to offer an alternative way of doing things. She gushes over blockchain technology, envisioning that Ethereum will help communities go green. She cites Steve Keen’s “Minsky” project as an alternative way to do macroeconomics, despite the fact that this project has produced no useful results whatsoever, and Keen is generally not seen as a credible figure among heterodox economists.

And at times, Raworth seems to cite no evidence beyond her own authority. In Chapter 6 she writes that artificial intelligence “is displacing people with near zero-humans-required production”. Even Daron Acemoglu wouldn’t make so bold a claim. Raworth provides no citation.

This is not to say that everything in Raworth’s book is wrong; far from it. In fact, many of the critiques she levels at mainstream economics are perfectly valid and reasonable — even some of the ones where her supporting evidence is weak. But the book is so eager to launch every possible missile at the discipline of economics that it comes off more as a polemic than a scholarly analysis.

And in doing so, Doughnut Economics fails at the central task it sets out to complete. It does not offer a coherent new paradigm for doing economics. Instead, it offers a hurricane of unrelated critiques and a laundry list of policy goals. It vividly demonstrates that the “heterodox” economics project has not escaped its fundamental dilemma — its relevance is still entirely dependent on the continued intellectual hegemony of the paradigm it was created to challenge.

A big problem for the heterodox movement was that most of the really brilliant thinkers who tried to create alternative models — people like Joe Stiglitz, Thomas Piketty, Esther Duflo, Richard Thaler, Dani Rodrik, Paul Romer, and so on — had been co-opted into mainstream academia. That left the heterodox movement mostly headed by people with very strong leftist politics but with only a weak grasp of the ideas they were critiquing.

Both of these diagrams are actually much older than the Paul Samuelson-style mathematical economics that came to prominence in the 1960s/70s, and against which the heterodoxers typically rail.

In fact, their index has 57 different indicators!! It’s incredibly comprehensive and complex, and yet at the end of the day it’s highly correlated with good old GDP.

Or you invest it in risky, appreciating assets like stocks, which gives a windfall to the rich people who own those assets.

This is known as the Environmental Kuznets curve. Despite its limited domain of applicability, I’m especially fond of it, because a long time ago, my family changed their name from Kuznets, which means “Smith” in Russian.

Actually, there is now some causal evidence on this. For example, Colmer et al. (2025) find that rising incomes do result in less air pollution at the local level.

Sometimes I think the world has an oversupply of smart and "smart" people. With an undersupply of humble insightful thinkers.

Paradigm changers know in almost every case, absolutely everything about the "giant shoulders they stand on".

Galileo knew all about the world of Aristotle and Stole my.

Newton knew everything about them and Galileo and Copernicus.

Einstein and Bohr knew everything that Newton knew.

Even Steve Jobs, Bill Gates knew everything about the science and technology of computers and software.

I do appreciate that the Paradigms of Macroeconomics have fuzzy and sometimes amorphous boundaries.

Good review!

Wonderful! This is one of the last books my late partner read before he died. He built two med tech companies, took both public, sat on several corporate boards & was a venture investor. He understood economics and thought we needed a broader lens for defining a healthy economy. He recommended the book so I read it after his death. I was disappointed. Raworth reminds me of education pundits who have inspiring ideas for transforming learning but little understanding of what society expects from schools. Your critique is thorough & clear. Thanks!