Book Review: "Breakneck"

In which Dan Wang offers a compelling theory of China vs. America.

There was a time in 2016 when I walked around downtown San Francisco with Dan Wang and gave him life advice. He asked me if he should move to China and write about it. I told him that I thought this was a good idea — that the world suffered from a strange and troubling dearth of people who write informatively about China in English, and that our country would be better off if we could understand China a little more.

Dan took my advice, and I’m very glad he did. For seven years, Dan wrote some of the best posts about China anywhere on the English-speaking internet, mostly in the form of a series of annual letters. His unique writing style is both lush and subtle. Each word or phrase feels like it should be savored, like fine dining. But don’t let this distract you — there are a multitude of small but important points buried in every paragraph. Dan Wang’s writing cannot be skimmed.

I’ve been anticipating Dan’s first book for over a year now, and it didn’t disappoint. Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future brings the same style Dan used in his annual letters, and uses it to elucidate a grand thesis: America is run by lawyers, and China is run by engineers.

Dan starts the book by recapitulating an argument that I’ve often made myself — namely, that China and the United States have fundamentally similar cultures. This is from his introduction:

I am sure that no two peoples are more alike than Americans and Chinese.

A strain of materialism, often crass, runs through both countries, sometimes producing veneration of successful entrepreneurs, sometimes creating displays of extraordinary tastelessness, overall contributing to a spirit of vigorous competition. Chinese and Americans are pragmatic: They have a get-it-done attitude that occasionally produces hurried work. Both countries are full of hustlers peddling shortcuts, especially to health and to wealth. Their peoples have an appreciation for the technological sublime: the awe of grand projects pushing physical limits. American and Chinese elites are often uneasy with the political views of the broader populace. But masses and elites are united in the faith that theirs is a uniquely powerful nation that ought to throw its weight around if smaller countries don't get in line.

It's very gratifying to see someone who has actually lived in China, and who speaks Chinese, independently come up with the same impression of the two cultures! (Though to be fair, I initially got the idea from a Chinese grad student of mine.)

If they're so culturally similar, why, then, are China and the U.S. so different in so many real and tangible ways? Why is China gobbling up global market share in every manufactured product under the sun, while America’s industrial base withers away? Why did China manage to build the world’s biggest high-speed rail network in just a few years, while California has yet to build a single mile of operational train track despite almost two decades of trying? Why does China have a glut of unused apartment buildings, while America struggles to build enough housing for its people? Why is China building over a thousand ships a year, while America builds almost zero?

Dan offers a simple explanation: The difference comes down to who runs the country. The U.S. has traditionally been run by lawyers, while the Chinese Communist Party tends to be run by engineers. The engineers want to build more stuff, while lawyers want to find a reason to not build more stuff.

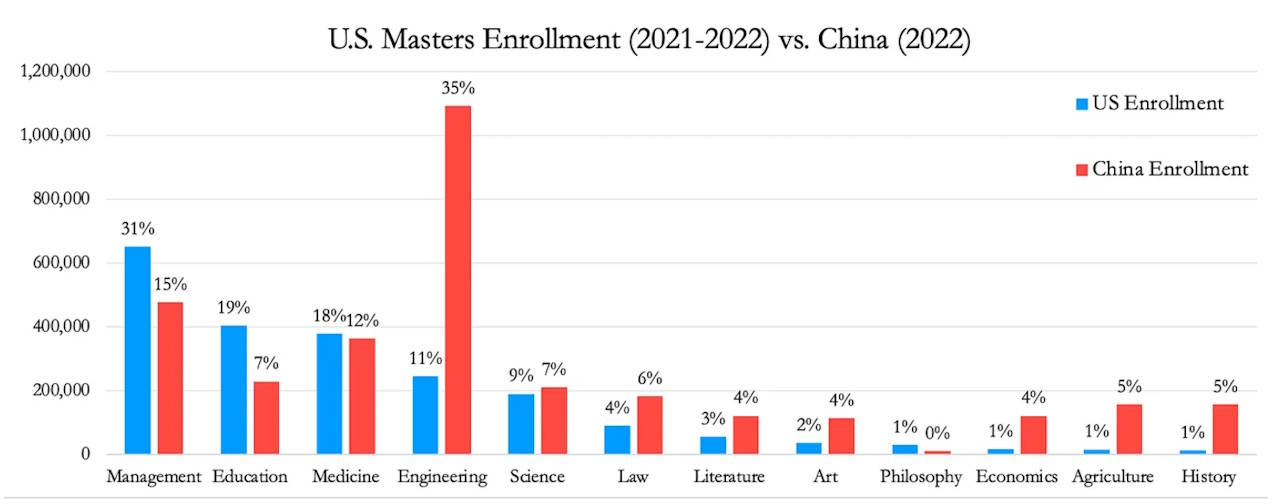

Dan tends to base his arguments on anecdotes and examples, but it’s good to get some raw data here. Jonathon P. Sine, another China watcher, has a long review of Breakneck that includes some excellent charts. One of them shows just how much more likely Chinese students are to study engineering, compared to their American counterparts:

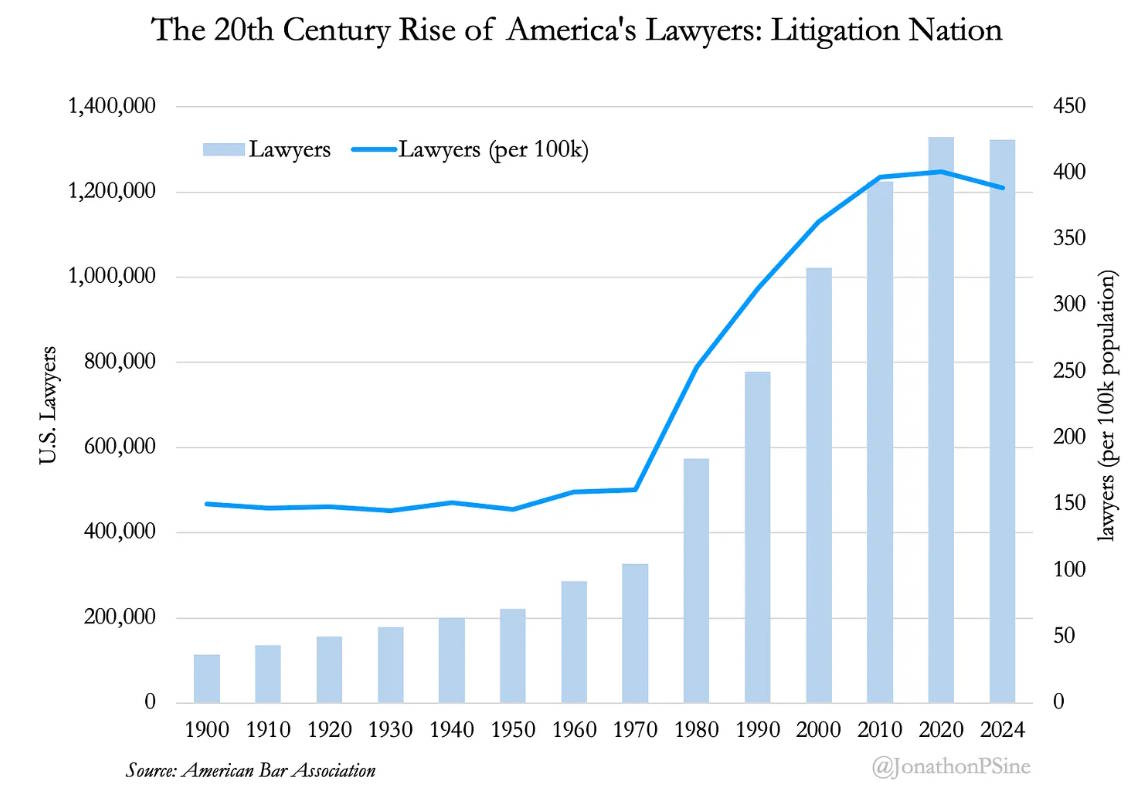

Meanwhile, between 1970 and 2020, the number of lawyers in America rose enormously relative to the population:

And thanks to this surge, the U.S. now has more lawyers per capita than almost any other rich country.

But Dan’s thesis about lawyers and engineers isn’t just about the professional classes and their occupational choices; it’s also about who rules the country. He points out that most American politicians have always tended to be lawyers, while most members of the CCP’s Politburo traditionally tended to have engineering backgrounds.

Dan argues that rule by engineers biases the state toward building things — factories, infrastructure, and housing. Engineers are “do-something” types who feel more comfortable planning specific projects than developing or adjudicating policy rules. The main downside of China’s engineer-dominated culture, he argues, is social — the engineers in charge of the CCP are also always trying to plan out Chinese society the way they would plan a bridge or a factory.

This can lead to severe repression; Dan cites the One-Child Policy and the Covid lockdowns as instances where social planning went horribly awry. The chapters of Breakneck that tell the stories of these policy failures are incredibly eye-opening.1

Meanwhile, Dan argues that the lawyers who dominate America prioritize blocking development instead of encouraging it. His arguments and examples are very similar to those you’d find in Abundance or Why Nothing Works, making Breakneck a good companion to those other volumes.

Breakneck’s thesis generally rings true, and Dan’s combination of deep knowledge and engrossing writing style means that this is a book you should definitely buy. Its primary useful purpose will be to make Americans aware that there’s an alternative to their block-everything, do-nothing institutions, and to get them to think a little bit about the upsides and downsides of that alternative.

In case you’re interested, Dan and I had an hour-long discussion about his book the other day, facilitated by James Cham:

In that video, I bring up my main concerns about Dan’s argument: How do we know that the U.S.-China differences he highlights are due to a deep-rooted engineer/lawyer distinction, rather than natural outgrowths of the two countries’ development levels? In other words, is it possible that most countries undergo an engineer-to-lawyer shift as they get richer, because poorer countries just tend to need engineers a lot more?

I am always wary of explanations of national development patterns that rely on the notion of deep-rooted cultural essentialism. Dan presents America’s lawyerly bent as something that has been present since the founding. But then how did the U.S. manage to build the railroads, the auto empires of Ford and GM, the interstate highway system, and the vast and sprawling suburbs? Why didn’t lawyers block those? In fact, why did the lawyers who ran FDR’s administration encourage the most massive building programs in the country’s history?

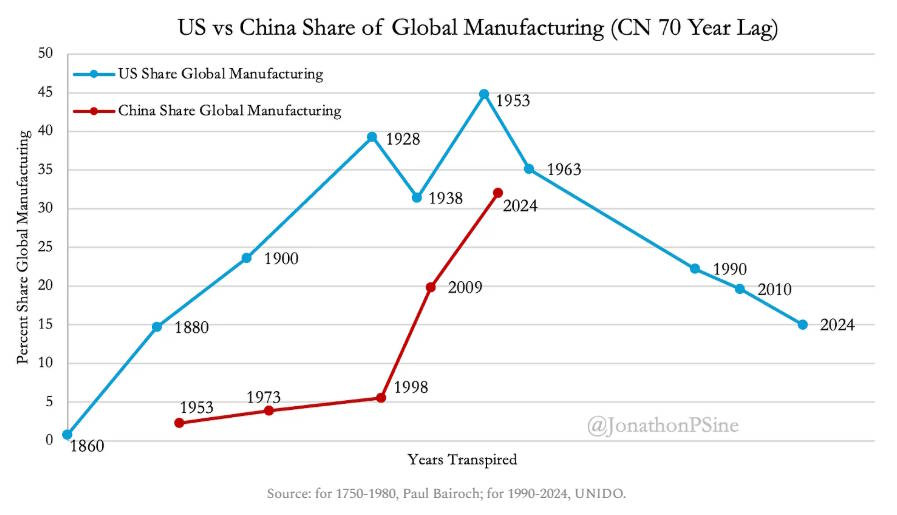

In fact, as Sine shows in another post, the U.S. dominated global manufacturing between the 1920s and the 1960s to about the same degree that China does now:

And keep in mind that America achieved this titanic share of global manufacturing while having a much smaller percent of world population than China does.

That’s an impressive feat of building! So even though most of America’s politicians were lawyers back during the 1800s and early 1900s, those lawyers made policies that let engineers do their thing — and even encouraged them. It was only after the 1970s that lawyers — and policies made by politicians trained as lawyers — began to support anti-growth policies in the U.S.

An international example is also useful here. As anyone who has read MITI and the Japanese Miracle will know, Japan’s legendary bureaucracy has been traditionally staffed almost entirely by law majors. Yes, Japan makes policy much more by bureaucratic administration than by litigation and court rulings. But if educational background were the key to a having a lawyerly versus an engineering society, Japan would come down squarely in the lawyer camp.

And yet instead, Japanese capital investment levels have always been much higher than U.S. levels, and manufacturing has been a much bigger percent of its GDP. Having leaders who majored in law doesn’t appear to automatically deindustrialize a country; Japan’s law majors are simply not trained to think that blocking growth is their job.

There are several alternative explanations for the trends Dan Wang talks about in his book. One possibility, which Sine argues for, is that China’s key feature isn’t engineering, but communism (or more specifically, what Sine and others call “Leninism”). Engineers like to plan things, but communists really, really like to plan things — including telling people to study engineering.

Another possibility is that engineering-heavy culture is just a temporary phase that all successfully industrializing countries go through during their initial rapid growth phase. When a country is dirt poor, it has few industries, little infrastructure, and so on. Basically it just needs to build something; in econ terms, the risk of capital misallocation is low, because the returns on capital are so high in general. If you don’t have any highways or steel factories, then maybe it doesn’t matter which one you build first; you just need to build.

There’s also the O-ring theory of economic development, which says that countries with otherwise high potential can fail to grow if they’re hampered by a few gaps in terms of policy, technology, or institutions. If this is true, it’s a coordination failure, and it means government has to step up its role and plan to plug those holes.

So for a poor country like China in the 2000s, mobilizing resources is probably more important than allocating resources. But for an upper-middle-income country like China in the 2020s — and even more so for America in the late 20th century — allocation might become much more important. Diminishing returns on capital mean a rich society has to make more hard choices about where to send scarce resources.

Those choices can be made with central planning, of course. But as we discovered again and again over the 20th century, the better way to solve the allocation problem is with policy. If we design the rules of the market well, private companies can often solve the capital allocation problem on their own.

Lawyers are people whose job is to understand the rules of the game. That probably makes them better at redesigning and optimizing those rules. Lawyers — or at least, social scientists — might have looked at Xi Jinping’s industrial policy and realized that it set up a perverse incentive structure where every province is subsidized to have its own local champion in industries like auto manufacturing, thus competing down the profits of China’s true national champions while sucking up taxpayer money. That is not an especially well-designed policy.

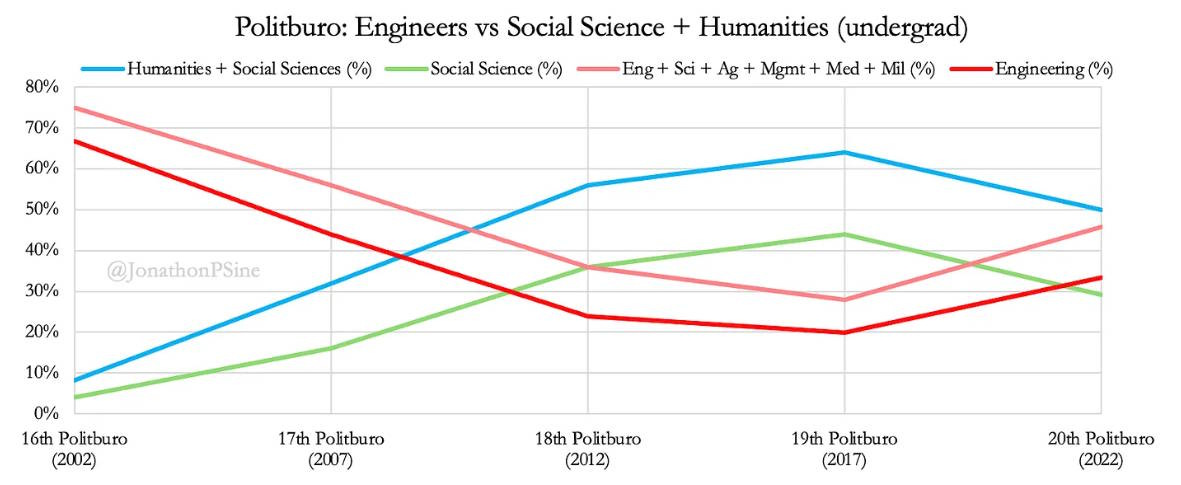

In fact, Sine shows that until the pandemic, the CCP Politburo’s membership was shifting steadily away from engineers and toward social science majors:

The uptick in engineers at the end is the shift toward engineering that Dan talks about in his book. Xi Jinping has been consciously trying to put more engineers in charge in China, in keeping with his dream of dominating global manufacturing.

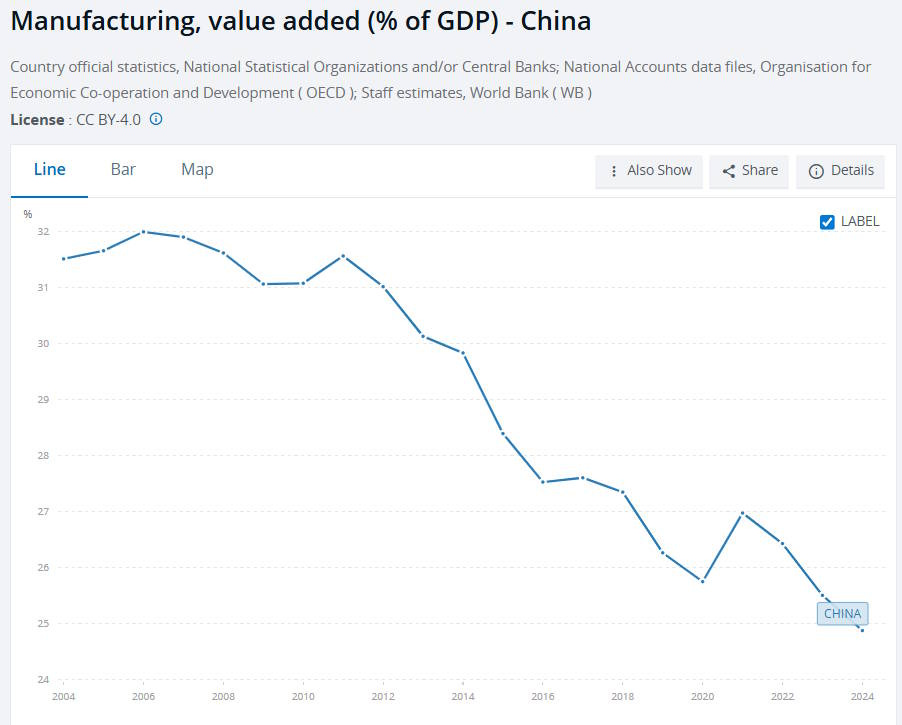

But Xi’s big push for manufacturing — and the resulting surge in exports that we’re calling the Second China Shock — might end up being a dead cat bounce. Manufacturing is relentlessly declining as a share of both employment and GDP:

In other words, it may simply be every rich country’s destiny — whether it’s ruled by lawyers or by engineers — to transition from a “just build it” engineering-type culture to a fussy rules-and-procedures culture dominated by lawyers and economists.

This shift can be managed in better and worse ways, and it’s likely that America’s litigious behavior is a highly suboptimal approach. Dan Wang is very right about the woes of our “just sue them” culture. Yes, Chinese companies aren’t profitable, but at the end of the day, China will have houses and plentiful power plants and trains, and America…will simply not.

So anyway, Breakneck is an important and incredibly provocative, thoughtful book. You should definitely read it. But as you read it, you should wonder whether modern China is best modeled as “America with different leaders”, or “America 75 years ago.”

These chapters also explain why the book’s title is a pun.

Thanks for this review, Noah. I have to say, I find your explanation of this phenomenon - that it has to do with different "levels" of economic development - more convincing than Dan's engineer-versus-lawyer one. This is not to say that his observation itself is wrong: I think he makes a very good case for it, and it's almost self-evidently correct.

I'd disagree with his point about the impact, however, for two of the reasons you highlighted:

(1) The US has pretty much always been run by lawyers. Most western countries have been since they adopted constitutional governments. But they have been much better at building before than now, so what gives?

(2) The causality of the engineer-lawyer split, inasmuch as it exists, might run the other way: the can-do government selects for engineers, rather than the reverse.

The development argument makes more inherent sense, I think. When people don't have access to secure food, housing, and transport, this is what they prioritise. That means building the infrastructure to provide that. Once you do, your concerns move on to other things - especially all the noise, disruption, and possible environmental damage that building that infrastructure comes with.

I had a couple of additional thoughts too:

(1) Maybe an alternative thesis is that when, say, the US and UK industrialised, academic disciplines were less specialised, and it was more common to find well-educated people with interests in diverse fields. The west might have been run by lawyers, but the relative prevalence of polymaths meant those lawyers were more engineer-ey, and less lawyerly than now. Building a ton with 19th and early 20th century lawyers was maybe possible, in a way that it wasn't with late-20th century and 21st century ones.

(2) If the development thesis is right, is it possible for a country to go in the opposite direction? I.e. for the stasis in building stuff to cause such severe shortages of basic public goods that political support swings back towards can-do. This might be happening to a limited extent in the UK, but I'm not super convinced.

I'm looking forward to reading this book. My initial reaction on reading some of the initial reviews is to try and avoid thinking of engineering-led as "better" than lawyer-led or vice versa. Americas legal principles, individual and property rights, and rule of law have been undoubtedly tremendous in ensuring its greatness; I'm sure we can all think of engineering cultures that ignore these things for the sake of "getting things built" as delivering some pretty terrible outcomes - not least of all in China itself, as well as closer to home more recently perhaps with the event of social media.

What an amazing outcome it would be if we could see a strong, visionary, innovative engineering discipline and culture develop again, combined with respect for the rule of law enshrined with a robust set of legal rights and judiciary to back them up. Now thats an America we could all respect again (signed, a non-American).