At least five things for your weekend (#30)

"Are we better off", the economy of Dune, energy abundance, wacky polls, doomscrolling, anger about interest rates, and visualizing urban density

Some weeks there’s not much to write about, and then some weeks stuff just all seems to happen at once. This week is one of those. There’s Biden’s State of the Union, the latest attempt to ban TikTok, a very important primary election in San Francisco, and more. I’m going to be writing about all of those events in the next few days, but in the meantime, my list of interesting things to write about is getting unmanageably long. So I’m going to have to do a few more and longer roundups, just to keep on top of everything.

Anyway, first, let’s do podcasts. My friend Stephanie Sher (a tech investor and AI person) and I did a very interesting appearance on our friend Noor Siddiqui’s podcast, which is called Conceivable. Noor runs a startup called Orchid that does genetic screening for IVF, so she talks about a lot of topics related to fertility and childbearing. Steph wanted to do an episode about dating and romance in the tech world, and I somehow ended up getting roped into this. It’s not a topic I typically talk about, but I like to think I added some interesting perspectives to the mix. We don’t have video, due to a technical error, but the audio is pretty fun:

And here it is on Apple Podcasts.

I also did two episodes of Econ 102, with Erik Torenberg. Here’s one about building a multiracial society. It was inspired by Google’s Gemini fiasco, but we end up not even talking about that, and just talking about nationalism and belonging and such.

Here are Apple Podcasts and YouTube.

The next episode had a guest, Brad Hargreaves, who writes about real estate. We had a rousing discussion about — you guessed it — the real estate industry and housing. It was pretty fun.

And here are Apple Podcasts and YouTube.

Anyway, on to this week’s list of at least five interesting things! There are seven items this week, which is technically at least five.

1. Are we better off than in 2019?

Every presidential election, the challenger or their supporters ask the famous Ronald Reagan question from 1980: “Are you better off than you were four years ago?”. They’re hoping that, like Reagan voters in 1980, people will answer “No,” and vote out the incumbent.

This week, in advance of Biden’s State of the Union speech, it was Congresswoman Elise Stefanik asking that question:

Many people jumped on Stefanik to answer “Of course not.” After all, four years ago we were at the start of the Covid pandemic. 2020 will always be remembered for massive unemployment, lockdowns, riots, soaring crime, and a million deaths from disease. It was not fun.

But to simply give that answer and declare victory is way too easy. People intuitively understand that Trump wasn’t responsible for most of the horrors of 2020. They will tend to view 2020 as an interregnum between the Trump and Biden presidencies. So when they think about the question “Are you better off?”, they’re going to think about whether they’re better off compared to 2019 — the year before the pandemic, when the economy was strong, employment was high, inflation was low, and so on.

And the thing is, even compared to 2019, most Americans are better off — at least in a purely economic sense.

I mean, just look at how much Americans consume. Here’s real personal consumption expenditures — “real” meaning “adjusted for inflation”:

Because this number is adjusted for inflation, this is not a case of “people spending more because they have to, because of higher prices”. This is just people buying more actual stuff. About $5000 more per year, measured in 2017 dollars. That’s kind of a lot!

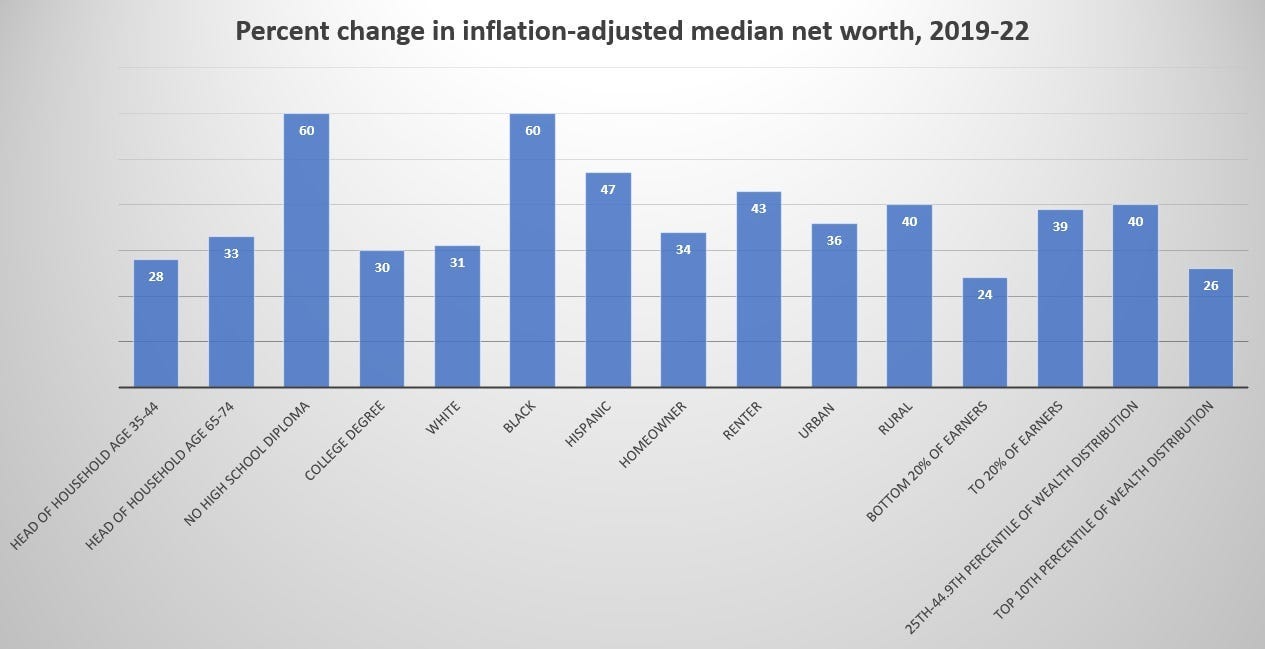

Now, is that because people are spending down their wealth? Well, no — at least, not by 2022. Between 2019 and 2022, Americans got richer across the board:

Part of this is because stock and housing prices have gone up. But part is because Americans used their income during the pandemic — including government support — to pay down a lot of their debt. Household debt to GDP is lower than it was in 2019, and household debt payments as a percentage of disposable income are lower too, despite much higher interest rates.:

Americans are spending more in large part because they’re earning more. Here’s median real weekly earnings for full-time employees, measured with two different measures of inflation:

The red line is measured with PCE, which puts more weight on health care prices, while the blue line uses CPI, which puts more weight on housing. Either way, median weekly earnings have increased. And if you look at average wages, you get the same picture:

The increases since 2019 aren’t huge, and they were interrupted by the sharp decline in late 2021 and early 2022 (the 2020 pandemic numbers are abnormal and you can pretty much ignore them). But the gains are real.

And of course, employment rates are as high as they were in 2019.

This doesn’t mean that every single economic indicator is better now than it was then. Inflation is a little higher. It’s harder to buy a house. And of course non-economic indicators are also a mixed bag — violent crime is still higher than in 2019, thanks to the 2020 surge, but coming down fast. Suicide is higher, as is homelessness.

So while I can’t say for sure whether you’re better off, I can say that in a purely economic sense, according to most indicators, most Americans are better off — not just compared to the dark days of the pandemic, but compared to the halcyon days of the pre-pandemic.

Which is not to say Trump was a bad steward of the economy. In fact, he was a pretty good steward of the economy. But Biden has been pretty good as well. One iron law of American politics is that nobody ever gets credit from the other side.

2. How Dune helps us understand the real-life Middle East

(This section contains spoilers for the Dune books.)

I recently saw Dune 2, and it’s really good, despite a bit of a rushed second half. I highly recommend it. Anyway, everyone gets that Dune is an allegory for the Middle East, with the Fremen as the Bedouins and the “spice” — which is necessary for interstellar transportation, longevity, and various other things — as the oil analog.

But the economic historian Mark Koyama has taken the idea further. In a recent paper and accompanying blog post, he argues that the dysfunctional empire depicted in Dune naturally springs from an economy that’s dependent on one very valuable natural resource.

He writes:

The political economy of the galactic empire is a form of what Douglass North, John Wallis, and Barry Weingast term “limited access orders”. Limited access orders are a form of government that achieve a measure of peace and society order through the creation of economic rents for elites…

The greatest source of rents is the spice that can only be harvested on Arrakis…[H]arvesting it is extremely capital intensive…It is thus a monopoly granted to whichever House holds Arrakis in fief.

Like oil riches, spice produces a resource curse. It leads to the concentration of autocratic power both on the planet and in the galaxy at large…The empire Paul conquers following his victory at the end of the first novel is at least as oppressive and even more violent than the previous…empire.

This is important for understanding why some countries get rich and others only get middle-class. Look at the GDP levels for the Middle East and Latin America — regions of the world with high levels of natural resource endowments per capita — compared with more poorly-endowed places like East Asia and South Asia.

The more poorly-endowed East Asia starts out poorer but grows much faster, and eventually passes up the rather stagnant resource-exporting regions. South Asia seems to be accelerating as well, and it’s not hard to imagine it also passing up the resource exporters in the future.

In other words, in a Dune-type universe, you don’t want to be Arrakis, whether it’s under the control of the Harkonnens or Paul Muad’dib. The dependence on spice will lead to a political economy where elites fight over control of the spice and generally leave the rest of society to hang. Fortunately, in our modern world, we have political units that are not ruled by resource exporters — the industrialized nations. It’s generally much nicer to be one of these. There are exceptions, of course — Australia is a very nice place to live, as are Norway and Chile. But in general, resource exporters face a very challenging political economy.

3. The new age of abundant energy

I don’t think most people realize what an age of energy abundance the human race is entering right now. There are two reasons for this. First, there’s the exponential cost decrease in solar power and batteries. Second, there’s the fact that America drilled for a lot of fossil fuels.

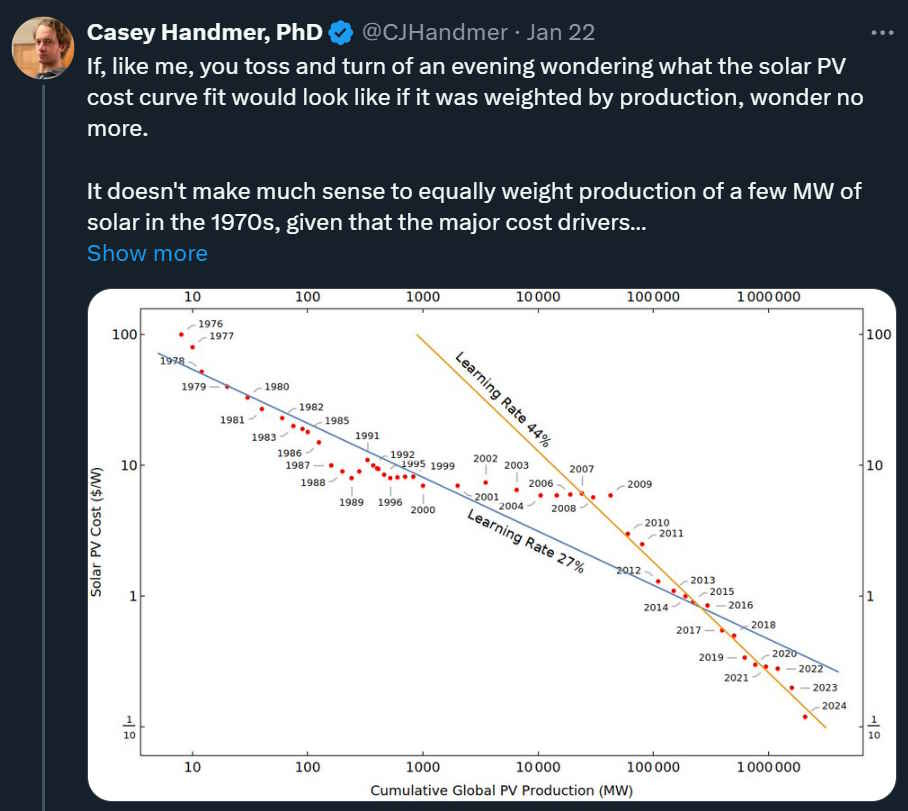

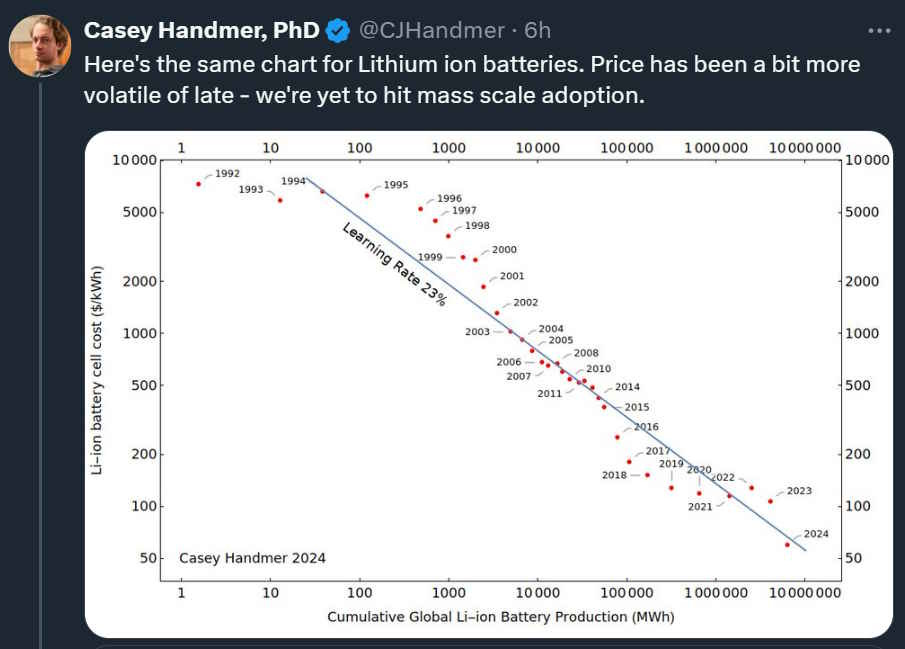

Casey Handmer points us to data on solar and battery scaling:

This means that the more solar and batteries we built, the cheaper it got to build yet more solar and batteries. Will these cost declines continue? No one knows; the solar cost curve decelerated in the late 2000s (due to high commodity prices) and then massively re-accelerated in the 2010s (due to Chinese production), so these scaling laws aren’t quite as steady as, say, Moore’s Law.

But as Handmer points out, we really haven’t deployed that much solar and battery power yet, compared to how much we plan to deploy. That leaves lots of scope for much further cost declines. This will be more important in batteries than in solar, since solar will come to be dominated by the cost of land. But in both cases, there’s every reason to believe that these energy technologies are going to get even cheaper.

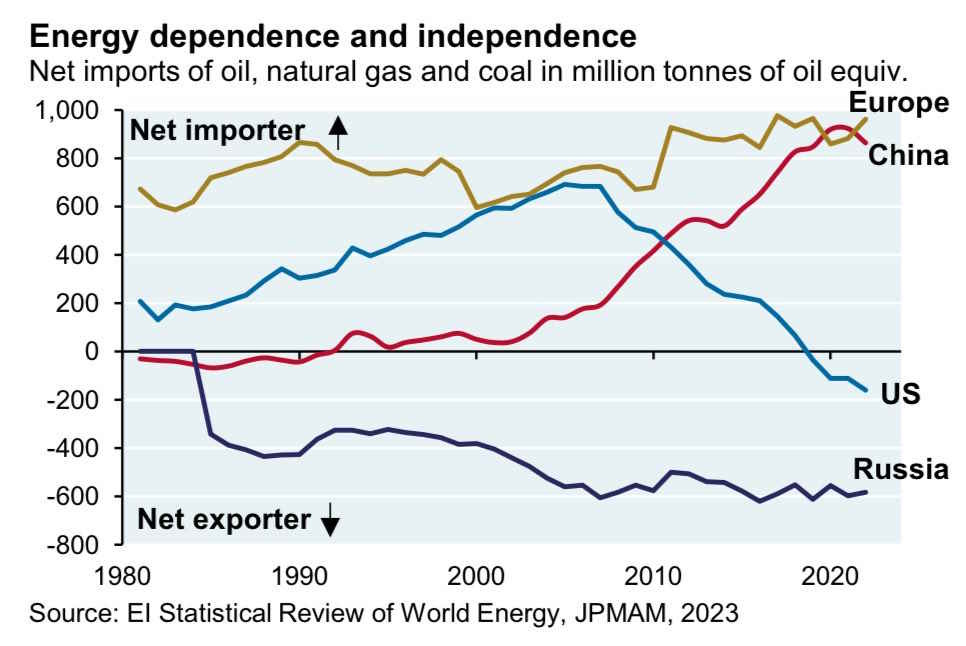

The other reason energy is getting more abundant is that the U.S. invented fracking, and used this to drill for a ton of oil and natural gas. Thanks to record U.S. oil output and record U.S. natural gas output, America is energy independent for the first time in over 40 years:

This is in large part thanks to the Biden administration’s pivot. Biden came into office expecting to be an anti-fossil-fuel President, but when the Ukraine war started, he pivoted to “drill, baby, drill”, in order to compete with the Russians.

Obviously, fossil fuels are bad for the climate, while green energy is good. Eventually green energy will overtake and replace fossil fuels, but in the meantime the extra fracking will produce a small bump in carbon and methane emissions.

But I think that instead of looking at the age of energy abundance entirely through a climate lens, we should think about it in terms of all the cool physical technologies we might use this bonanza to build. The last age of energy abundance — the oil age, in the early 20th century — gave us cars and airplanes and cheap shipping. The advent of cheap solar and batteries could give us cheap metal production, cheap recycling, cheap desalination, cheap robotics, and any other number of cool futuristic stuff.

In fact, some people argue that it was our failure to find anything better than oil in the late 20th century (partly because we refused to build enough nuclear power) that we experienced a productivity slowdown since 1973. If so, the return of cheap energy might give us a new boom. Fingers crossed.

4. Be suspicious of wacky polls

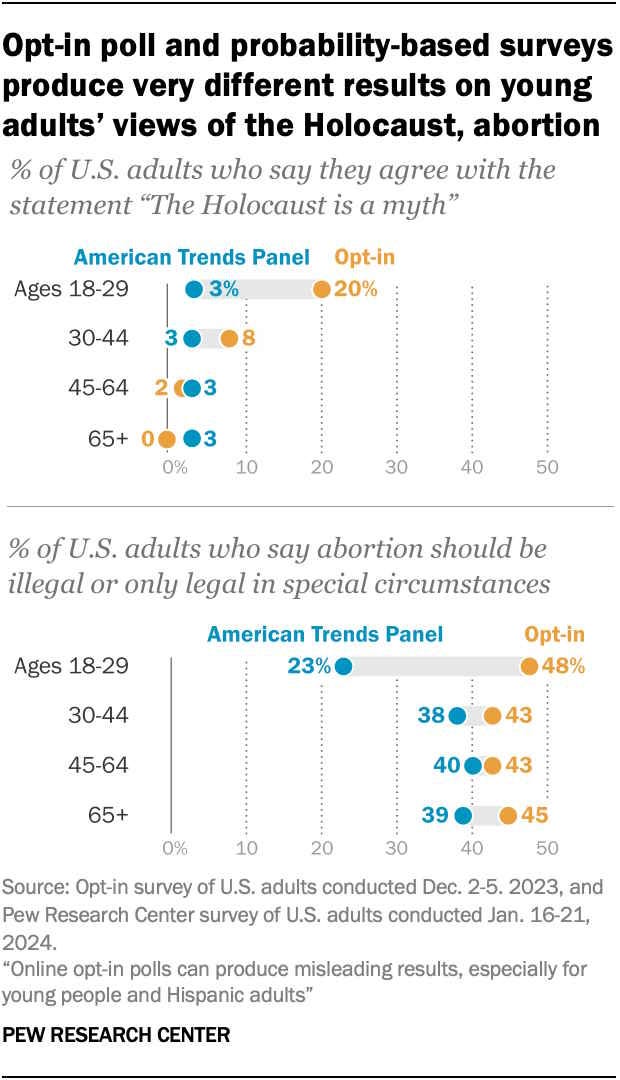

A couple months ago, there was a big freakout in the media about a survey showing that 20% of young Americans were Holocaust deniers:

A fifth of Americans ages 18-29 believe the Holocaust was a myth, according to a new poll from The Economist/YouGov.

While the question only surveyed a small sample of about 200 people, it lends credence to concerns about rising antisemitism, especially among young people in the U.S.

There was just one problem — the survey in question was complete crap. It was an “online opt-in poll”, meaning that it surveyed anyone who found the poll on the internet and decided to take it. Guess who tends to find internet polls by searching on their own? Trolls, and people who just want to give silly answers to polls. That's why opt-in polls tend to be much lower quality than polls where the survey taker selects the list of people to contact.

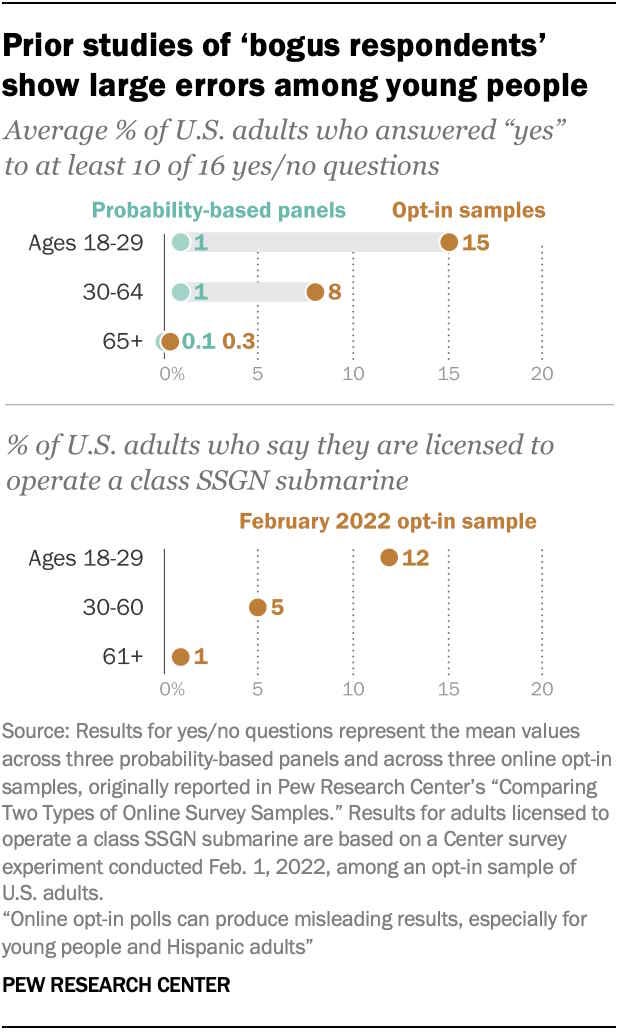

And of course the quality is especially low for surveys involving young people, who are highly likely to be trolls and pranksters searching the internet for polls to disrupt. For example, in 2022, 12% of respondents age 18-29 said they’re licensed to operate an SSGN-class submarine (the true number is effectively zero):

So opt-in online polls are not reliable at all. What do higher-quality surveys say? Pew’s American Trends Panel, a much more carefully done survey, found that only 3% of young Americans are Holocaust deniers, the same as among other age groups:

And even this low number could be inflated by trolls and pranksters giving intentionally false answers — the so-called “lizardman’s constant” that seems to afflict every poll in existence.

So the lesson here is: Do not freak out about a single poll showing that some large number of people believes in some crazy thing. At least check the poll’s methodology before you freak out, and preferably wait for some other polls to confirm the finding. Freaking out about bad polls is a waste of effort, attention, and mental health.

5. Doomscrolling is hazardous to your mental health

There is no shortage of studies correlating social media use with poor mental health. But this one, by de Mello, Cheung, and Inzlicht, really hits home for me:

In public debate, Twitter (now X) is often said to cause detrimental effects on users and society. Here we address this research question by querying 252 participants from a representative sample of U.S. Twitter users 5 times per day over 7 days (6,218 observations). Results revealed that Twitter use is related to decreases in well-being, and increases in political polarization, outrage, and sense of belonging over the course of the following 30 minutes. Effect sizes were comparable to the effect of social interactions on well-being. These effects remained consistent even when accounting for demographic and personality traits. Different inferred uses of Twitter were linked to different outcomes: passive usage was associated with lower well-being, social usage with a higher sense of belonging, and information-seeking usage with increased outrage and most effects were driven by within-person changes.

In other words, Twitter is exactly the outrage machine people think it is. It’s the Two Minutes Hate from Orwell’s 1984, except it lasts exactly as many minutes as you’re willing to give it. And no matter how fun you think it is to be outraged at stuff, it’s not good for your emotional well-being.

I have to be on Twitter for my job. Hopefully, you don’t.

6. Interest rates vs. vibes

Since 2021, consumer confidence has sharply diverged from the economic fundamentals that used to do a very good job of predicting consumer confidence. People are far more pessimistic than any of the old models can explain. Why?

One popular explanation is “vibes” — i.e., media narratives. Another explanation is interest rates. In a thread last summer, Twitter user Quantian (who, by the way, I still owe dinner after losing a bet on Bernie Sanders to win the 2020 nomination — a bet I made entirely to hedge my own idiosyncratic risk) claimed that that higher interest rates explain the discrepancy. Now Larry Summers, along with co-authors Marijn Bolhuis, Judd Cramer, and Karl Oskar Schulz, makes the same argument, with some more data:

Unemployment is low and inflation is falling, but consumer sentiment remains depressed….We propose that borrowing costs, which have grown at rates they had not reached in decades, do much to explain this gap…We show that the lows in US consumer sentiment that cannot be explained by unemployment and official inflation are strongly correlated with borrowing costs and consumer credit supply. Concerns over borrowing costs, which have historically tracked the cost of money, are at their highest levels since the Volcker-era…Global evidence shows that consumer sentiment gaps across countries are also strongly correlated with changes in interest rates. Proposed U.S.-specific factors do not find much supportive evidence abroad.

That is very interesting. Yet when I look at the timing of the drop in consumer sentiment in the U.S., the timing for this explanation seems off. Consumer sentiment fell 30 points from its pre-pandemic high from February 2020 to December 2021. But during that time, mortgage borrowing costs actually fell! By the time borrowing costs for American homebuyers started rising, most of the decline in consumer sentiment was complete:

That doesn’t rule out interest rates as an explanation, but it surely calls the idea that this is the main factor into question. Also, Summers et al. use global data from the OECD Consumer Confidence Index. But when the Financial Times’ John Burn-Murdoch looked at the numbers gathered by national statistics offices, he found that only the U.S. exhibited a divergence from fundamentals:

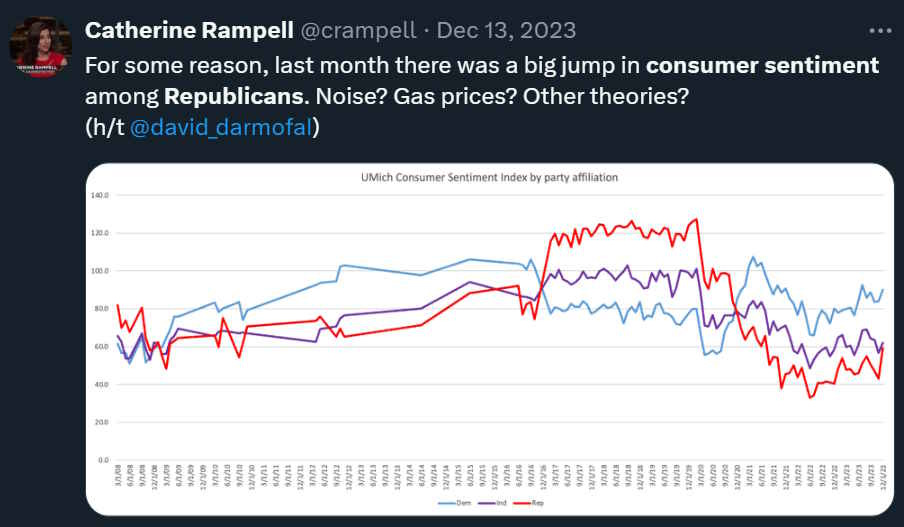

And furthermore, we see that the decline in consumer confidence is driven entirely by Republicans, whose sentiment crashed when Biden was elected, a year before rates started to rise:

The partisan divergence was even more abrupt and dramatic in other data sets.

So while I think interest rates are probably part of the story here, I still think there’s a lot of evidence pointing toward vibes as being pretty important.

7. A new way to visualize cities

In my last post, I explained what I think is Japan’s “secret sauce” for creating cities that are so nice even though they’re also very dense. One of the key elements is a great transit system. This allows people who don’t live in the city center to work and shop in the city center very easily.

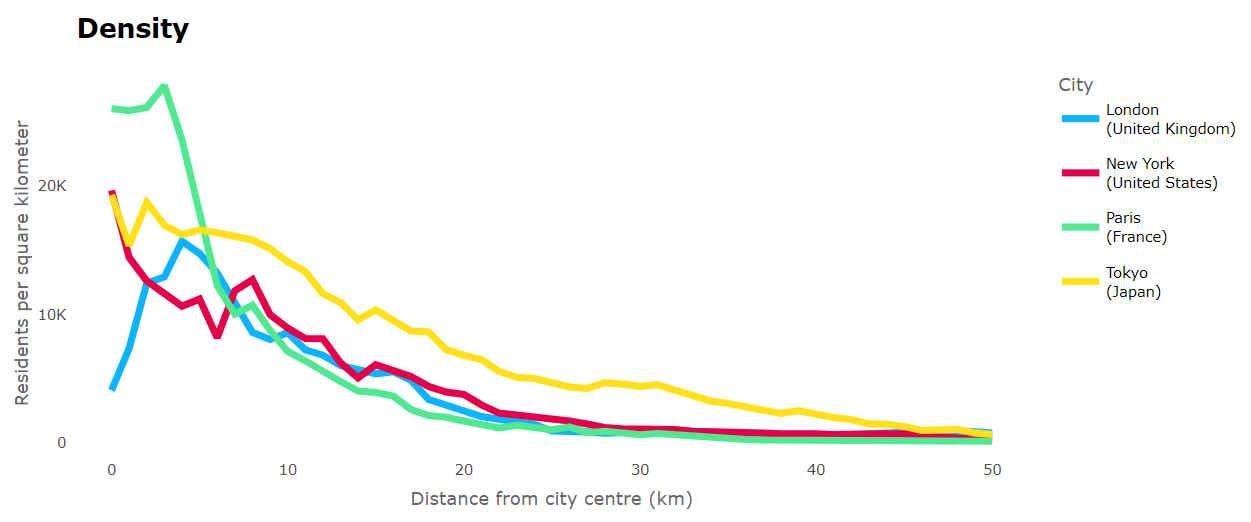

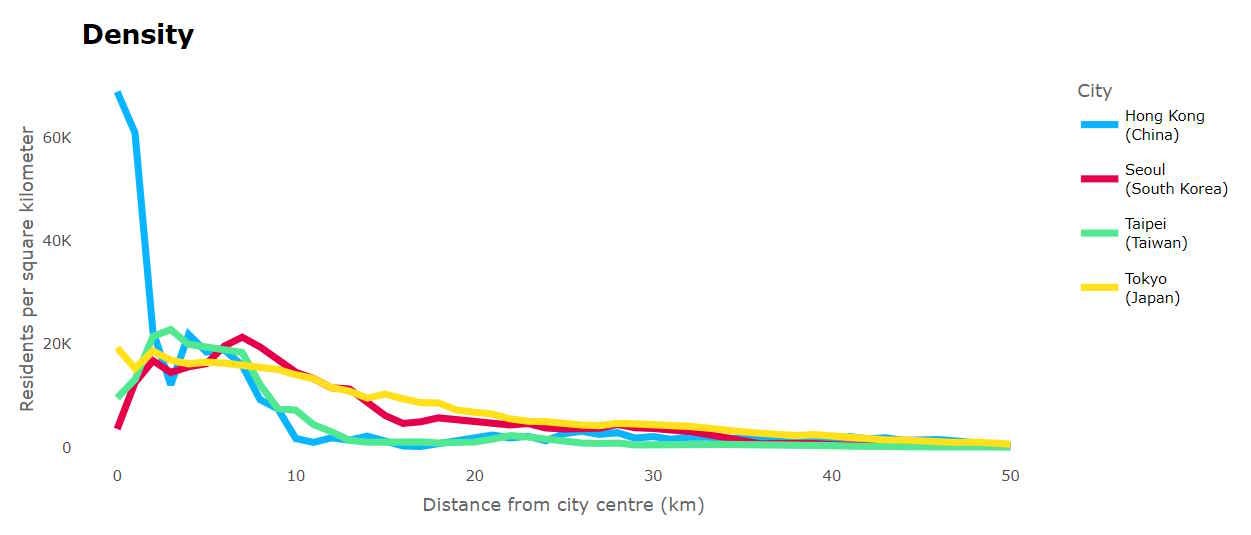

And we can see this when we look at where Tokyoites actually live. Jonathan Nolan has a cool new web tool at Citydensity.com that allows you to compare cities’ population density — that is, where the residents actually live — out to various distances.

So if we look at Tokyo compared to big Western cities, we see that at the city center, it’s not any denser. But once you get five or ten kilometers outside the center, Tokyo is much denser — the density doesn’t drop off nearly as fast.

In fact, Hong Kong and Taipei look more similar to the Western cities here, while Seoul looks more like Tokyo:

This gradually sloping density pattern allows Tokyo and Seoul to fit a lot more people without actually feeling any more crowded than Paris, Hong Kong, or New York City.

Two things make it possible. First, Tokyo and Seoul upzone their inner-ring suburbs, allowing dense construction far out from the city center. Second, both cities have excellent trains, which allows people who live in the dense inner-ring suburbs to commute into and out of the city center where the good jobs are.

Other cities should follow this development pattern if they can. Allowing more people to fit into the inner-ring suburbs of big cities will reduce the high rent in city centers, while also allowing more of a country’s population to be urbanized, raising productivity and protecting the environment in the process.

As a side note, I find it hilarious how Musk utterly failed with his rebranding of Twitter as X. Nobody, and I mean nobody, refers to it as just “X.” People either ignore “X” completely and just call it Twitter, or (most commonly) they say “X (formerly known as Twitter)” or some such. Or they make a portmanteau of the two names, as in Xitter.

Also, Twitter came with an obvious verb: to tweet. What verb means “to post on X”? To ex? To xeet?

Resource curse: It can be mitigated if ownership is dispersed among the population. It didn't happen in Texas because mineral rights belong to the land owner. Norway does the same thing with the sovereign wealth fund and Chile is not THAT dependent on copper.