At least five things for your Thanksgiving weekend (#20)

The OpenAI coup, "deaths of despair", Japan's stagnation, solar panel waste, and the Inequality Wars

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone! I hope you all had a lot of great food, and hung out with great people, and didn’t have bronchitis like I did. Oh well.

Anyway, I don’t have any new podcast episodes for you today — we recorded one this morning but it’s not out yet — but I do have five interesting economics-related things!

1. Why the EA coup failed

I was holding off on writing anything about the abortive attempted boardroom coup at OpenAI, partly because I don’t have that much to add to what others have said, and partly because I was waiting to see how the whole thing shook out. In any case, OpenAI itself seems relatively undisturbed, with Sam Altman back at the helm. The main fallout from the whole affair seems to be a general turn against the Effective Altruists whose concerns sparked the coup attempt:

[T]he OpenAI meltdown delivered another blow to the [EA] movement, which believes that carefully crafted artificial-intelligence systems, imbued with the correct human values, will yield a Golden Age—and failure to do so could have apocalyptic consequences…

Altman, who was fired by the board Friday, clashed with the company’s chief scientist and board member Ilya Sutskever over AI-safety issues that mirrored effective-altruism concerns, according to people familiar with the dispute.

Voting with Sutskever, who led the coup, were board members Tasha McCauley, a tech executive and board member for the effective-altruism charity Effective Ventures, and Helen Toner, an executive with Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology, which is backed by a philanthropy dedicated to effective-altruism causes.

In the wake of the failed coup, some EA supporters started to break ranks:

Perhaps the most important defection actually may have come from Nick Bostrom, whose book “Superintelligence” is basically the Bible of the AI safetyists. On a recent podcast, he declared that he was now more worried about efforts to slow AI down than about the AI risks that he has done so much to publicize.

Note that this isn’t a revolt against the “old” EA idea of maximizing the utility of charitable giving; it’s a revolt specifically against the new EA focus on AI risk.

Anyway, I think there’s a deep, fundamental reason that AI-focused EA blew its big chance. AI risk thinkers were always able to come up with lots of scary sci-fi scenarios about how generative AI could cause a global calamity. Those scenarios weren’t obviously impossible; it’s clear that they’re worth worrying about.

But when it came to recommendations for policy to diminish the risk of these scenarios becoming reality, the AI risk people were always short on actionable ideas. You can study how AI models work and try to understand them — Anthropic and others are working on interpretability. But because the really scary doomsday scenarios all depend on AI that’s much more advanced than what exists today, knowledge about how AI works now won’t necessarily help us avert those possibilities. The people who are scared of AI doomsday risk tend to believe in a “fast takeoff” in which AI goes very very rapidly from the GPT-style chatbots we know today to something more like Skynet or the Matrix. It’s basically a singularity argument.

“Fast takeoff” means that A) we basically can’t know much if anything about what AI will be like by the time it becomes truly scary, and B) it could jump to “truly scary” level at any minute. Thus the only action that most of the prominent AI risk people have been able to advise us to do is to “shut it all down” — to simply not make better AI.

And “shut it all down” is what the OpenAI board seems to have had in mind when it pushed the panic button and kicked Altman out. But the effort collapsed when OpenAI’s workers and financial backers all insisted on Altman’s return. Becuase they all realized that “shut it all down” has no exit strategy. Even if you tell yourself you’re only temporarily pausing AI research, there will never be any change — no philosophical insight or interpretability breakthrough — that will even slightly mitigate the catastrophic risks that the EA folks worry about. Those risks are ineffable by construction. So an AI “pause” will always turn into a permanent halt, simply because it won’t alleviate the perceived need to pause.

And a permanent halt to AI development simply isn’t something AI researchers, engineers, entrepreneurs, or policymakers are prepared to do. No one is going to establish a global totalitarian regime like the Turing Police in Neuromancer who go around killing anyone who tries to make a sufficiently advanced AI. And if no one is going to create the Turing Police, then AI-focused EA simply has little to offer anyone.

I see this as another case of a modern intellectual movement that is far better at identifying problems than it is at suggesting solutions. My prediction is that basically all of these movements will attract a lot of initial attention, but then gradually be ignored over time. The AI scenarios that EA folks suggest certainly are scary. But until EA comes up with some solution other than “shut it all down”, the people developing AI are simply going to pray for the serenity to accept the things they cannot change.

2. Challenges to the “deaths of despair” narrative

A few years ago, the Nobel-winning economist Angus Deaton started declaring that modern economics has gotten it all wrong. His argument is basically that recent reductions in life expectancy in America are due to the despair created by our capitalist economic system. He has a number of papers and a book laying out this idea.

I’m actually favorable to the “deaths of despair” idea, though my guess is that it’s more about stress than despair — behaviors like overeating and drug and alcohol abuse seem like coping mechanisms that can become addictive and destroy long-term health. But that’s just a guess. The fact is that just showing drops in life expectancy doesn’t really prove Deaton’s grand thesis about capitalism at all.

Essentially, we can boil Deaton’s story down to the following:

capitalism —> despair —> increased death

So far, most of the debate has focused on the second arrow — the question of whether falling life expectancy in the U.S. is due to despair. And most of that debate has focused on isolating which groups have been hit hardest by fentanyl, suicide, and so on — for example, the question of whether whites without a college degree have been hit harder. If you’re interested in that debate, Vox’s Dylan Matthews has a summary of some criticisms of Deaton, while Jonathan Rothwell mounted a spirited defense. I’m not sure whether these arguments will ever actually resolve the question of how many deaths are due to “despair”, since demography doesn’t actually tell us who’s despairing and who isn’t. I’m favorable to the idea that despair (or stress) is the organizing principle here, but we just need more data.

The more important point, however, is that neither Deaton nor any of his supporters have managed to establish a link between capitalism and despair. In a scathing and widely read post back in October, Matt Yglesias pointed out that Europe suffered a slowdown in productivity and income growth that’s similar to America’s, but saw no rise in “deaths of despair”. More generally, Deaton hasn’t managed to draw an empirical link between macroeconomic outcomes of any kind — inequality, slow income growth, income insecurity, rising service costs, or anything — and the drops in life expectancy that he talks about. And he doesn’t seem to even bother comparing America’s economic system to that of other rich countries, or analyzing whether those differences are responsible for divergences in life expectancy.

It’s this grand leap of interpretation, combined with a seemingly profound incuriousness about whether the data supports the leap, that makes Deaton’s anti-capitalist messaging so frustrating. If you’re going to claim that features of America’s economic system are causing more people to commit suicide or overdose on fentanyl, why not just test your claim? Empirical economics is chock full of ways to test that idea — there are plenty of natural experiments that you could use. Yet the Nobel Prize-winning economist seems content to simply do yet more demographic breakdowns of mortality rates. This does not yet satisfy the burden of proof.

3. How bad has Japan’s economy done since 1997?

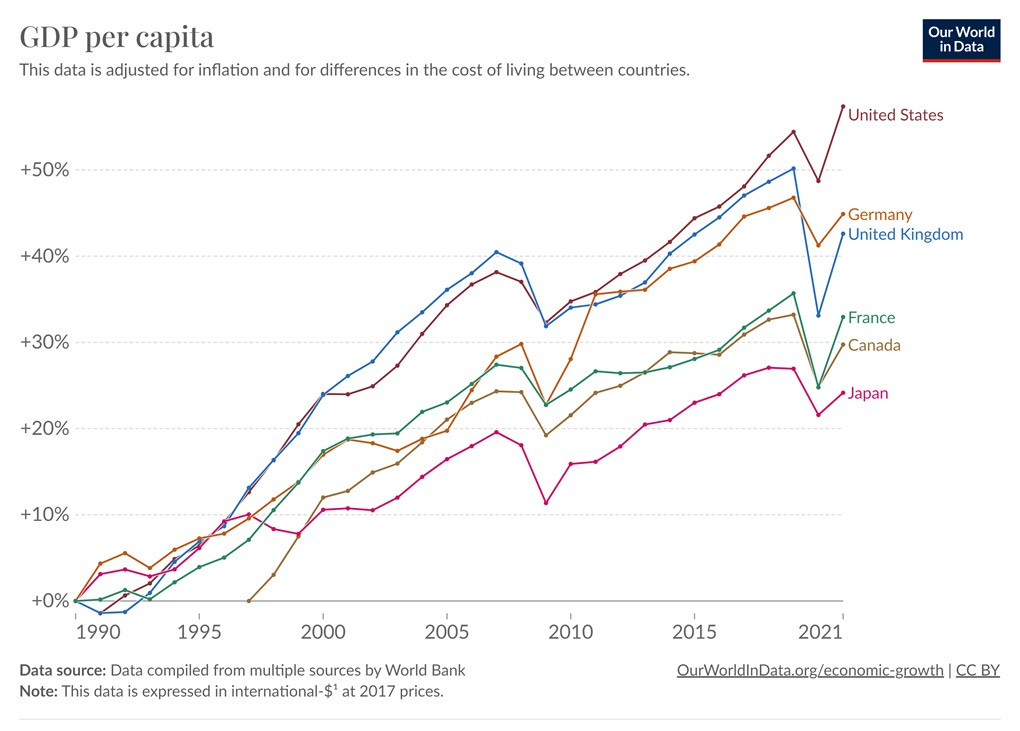

The conventional wisdom is that Japan has suffered multiple “lost decades” since its real estate bubble famously burst in 1990. In fact, if you look at per capita GDP, Japan seems to underperform other rich countries starting not in 1990, but in 1997, around the time of the Asian financial crisis:

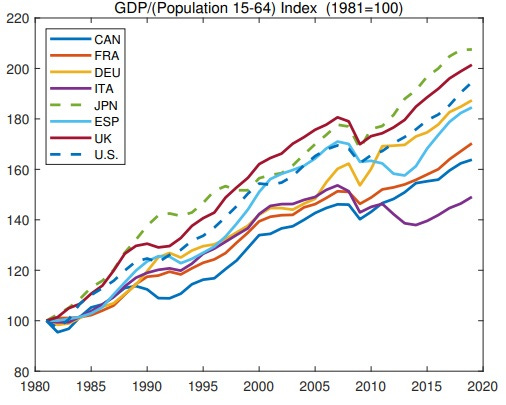

A typical counterargument to the “multiple lost decades” idea is that most of Japan’s apparent stagnation is just due to population aging, and that in terms of actual productivity Japan has done just fine since around 2000. A new paper by Fernandez-Villaverde, Ventura, and Yao makes this claim:

Due to population aging, GDP growth per capita and GDP growth per working-age adult have become quite different among many advanced economies over the last several decades. Countries whose GDP growth per capita performance has been lackluster, like Japan, have done surprisingly well in terms of GDP growth per working-age adult. Indeed, from 1998 to 2019, Japan has grown slightly faster than the U.S. in terms of per working-age adult: an accumulated 31.9% vs. 29.5%…

[O]nce we correct for population aging by focusing on output growth rates per working-age adult, Japan appears as a surprisingly robust economy over the last 25 years, outperforming the other G7 countries and Spain.

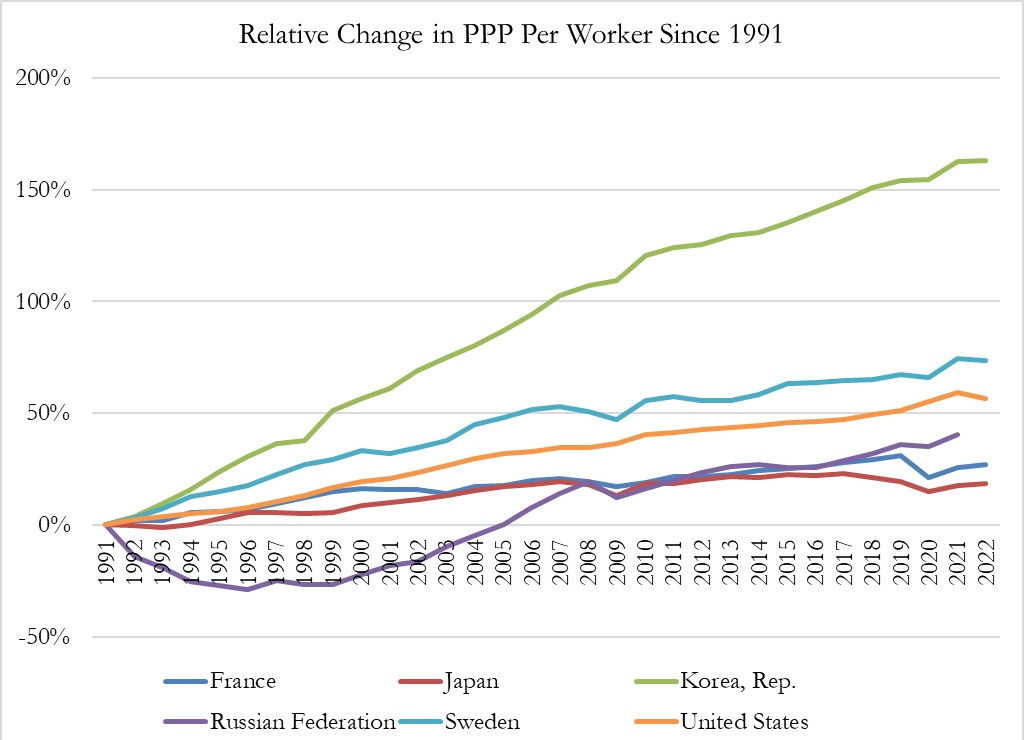

And here’s their graph:

Here you see poor performance in the early 90s, followed by a return to strong growth afterward — the standard “only one lost decade” story.

But not so fast! Not all working-age adults actually work. Lyman Stone points out that if you look at GDP per worker instead of GDP per working-age population, Japan again looks very slow:

And when you look at output per hour, the story is the same:

In other words, the only reason Japan has been able to beat these other countries in terms of GDP per working-age population is that it has put a lot more of its population to work.

Of course, some of this low productivity growth could also be due to aging, as there is a pretty robust empirical connection in the data. But the timing — a sudden flatlining of productivity growth after the Asian financial crisis of 1997, rather than after the bubble burst of 1990 — seems highly suspicious here.

Is it possible that the early and mid 90s weren’t actually a lost decade for Japan, but that the years since 1997 have been? This is a mystery that bears a lot more investigation, and I plan to write more about this soon.

4. Another bad argument against renewables, mostly debunked

I’ve been arguing that solar power is going to win the energy race, and provide us all with abundant cheap energy on demand. I’ve received a ton of pushback to that prediction, with solar skeptics throwing out numerous reasons why they think solar will never make it, even as countries around the world install the technology at breakneck speed. I’ve rebutted the skeptics’ arguments one by one, but there was one I never got around to rebutting — the idea that solar causes an unmanageable amount of waste.

Now Hannah Ritchie, one of my favorite climate bloggers, has done the work on solar waste (and wind waste too):

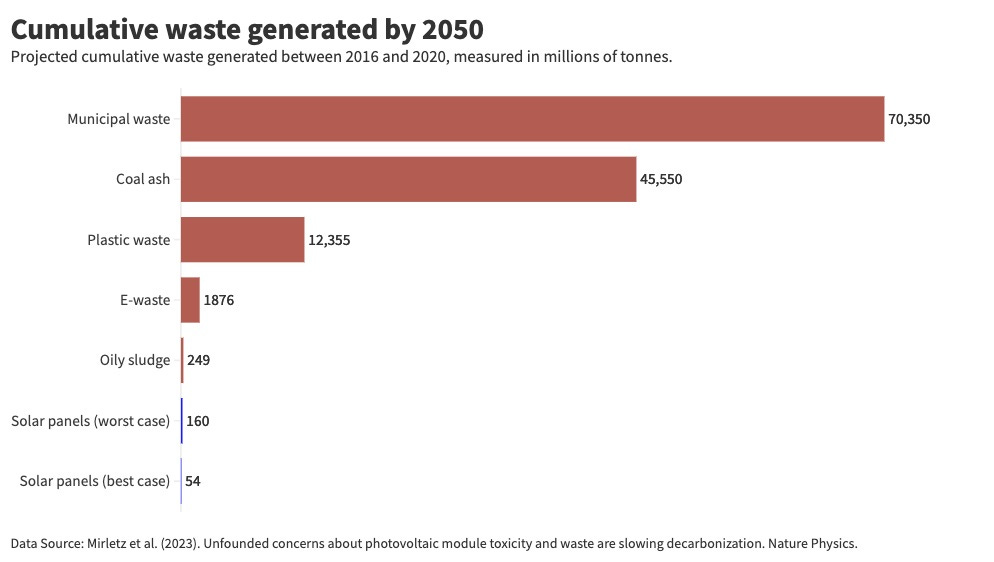

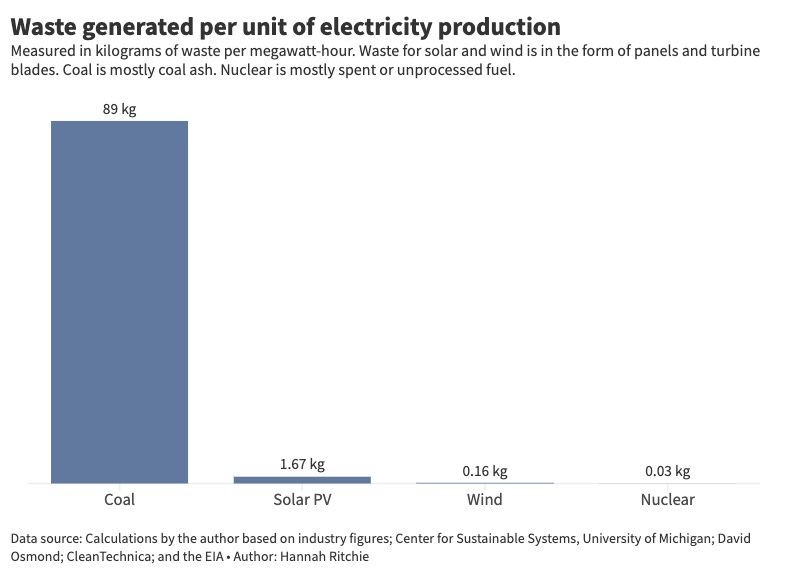

Her references are a 2023 paper by Mirletz et al. on solar panel waste and a 2017 paper by Liu and Barlow on wind turbine blade waste. Here are the relevant graphs:

The key fact here is that coal produces much much much more waste than solar or wind (or nuclear), but that we’ve learned to ignore coal waste and the health problems it causes. Solar is going to simply produce a lot less waste.

Nor will that waste be especially toxic. A lot of solar skeptics write to me that solar panels contain all sorts of harmful chemicals, but Ritchie points out that we’ve switched to panel technologies that don’t contain most of these chemicals:

US state health departments list a range of potential toxins in solar panels: arsenic, gallium, germanium, and hexavalent chromium.

Except, most panels are crystalline silicon or cadmium telluride (CdTe), which don’t have arsenic, gallium, germanium, or hexavalent chromium in them. More information on where some of these claims might come from is in the footnote.5

The only health concern from solar panels is the small amounts of lead in silicon panels and trace amounts of cadmium in CdTe ones. The International Energy Agency flags these as the only potential human health risk too.

In fact, engineers are working at removing the small amounts of lead from solar panels as well.

Once again, solar skeptics are inveterate techno-pessimists, and consistently underestimate humanity’s ability to innovate around early technological hurdles.

I will note, however, that Ritchie doesn’t compare solar to natural gas, which presumably produces a relatively low volume of solid or liquid waste. This is an important and necessary comparison. But simply showing that solar produces vastly less waste than coal power, which Americans lived with for many decades, shows that the solar waste problem is not going to be a deal-breaker.

5. The Inequality Wars rage on

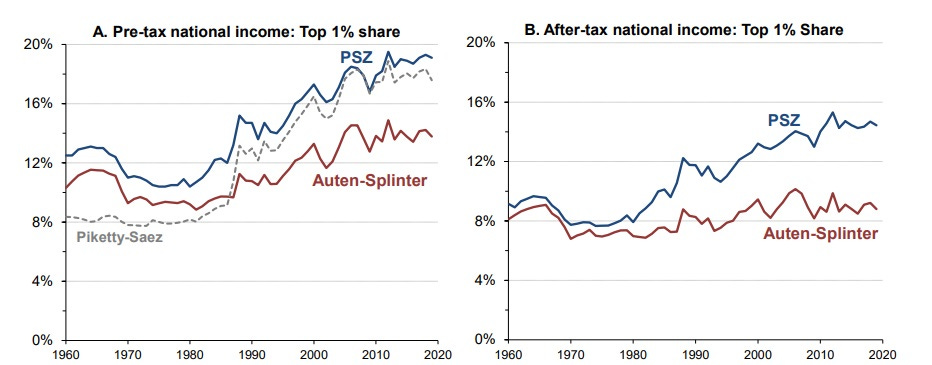

Back in the 2010s, there was a huge outcry over rising inequality. Economists like Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman rocketed to national prominence with their message that inequality was growing relentlessly and needed to be curbed with extremely high taxes. But there were always some economists who claimed that the rise in U.S. inequality was less dramatic than Piketty & co. claimed.

The most dramatic disagreements were usually about wealth inequality, which is inherently hard to measure. But there were arguments about income inequality too. Here’s what I wrote for Bloomberg in 2019:

Income inequality is also hard to measure…A lot of income is earned on paper by corporations, and there’s the question of how much of that actually belongs to the owners of those corporations…Another problem is how income is changed by taxes and transfers. Should a dollar of government health care spending count as a dollar of income for the recipients?

Different answers to questions like these can produce very different pictures of income concentration. Piketty and Saez estimated that the top 0.1% earned 12% of national income in 2012; the Federal Reserve and the Brookings team both came up with a number closer to 8%, only slightly more than in the late 1980s. Meanwhile, a 2018 paper by Piketty, Saez and Zucman finds that even after accounting for taxes and transfers, the top 1% went from taking about 10% of national income in the late 1980s to more than 15% by the mid-2010s. But a paper by Gerald Auten and David Splinter finds numbers closer to 7% and 9%, respectively. A Congressional Budget Office analysis gets numbers somewhere between the two, though a little closer to the French trio’s.

Anyway, this disagreement hasn’t gone away; in fact, it’s only gotten more vigorous. Auten and Splinter have a new paper in which they add even more adjustments, and find that the share of the top 1% hasn’t even increased at all compared to the 1960s! Here’s their graph, comparing their own numbers to those of Piketty, Saez, and Zucman:

How can these two teams of economists get such hugely different numbers, especially when they have access to the same data? Some of the disagreement between the two is due to disagreements about the data itself, especially concerning how much income people at the bottom of the distribution leave off of their tax returns. Auten and Splinter argue that it’s a lot more than Piketty et al. think. But a lot of the disagreement is also just due to different choices about what to count as “income”, and what not to count.

For example, does a dollar of health benefits count as a dollar of income? Maybe people don’t actually value health benefits at a 1-to-1 ratio with cash. I know that if I had an employer who decided to pay me by sending $500,000 worth of pudding to my house, I would not view this as being the same as getting paid $500,000. But maybe health benefits are just about as valuable as cash? It’s hard to know.

There’s also the question of imputed rent. If you own your own home, you have lower housing expenses than someone who rents. That income that you save each month from not having to pay rent is called “imputed rent”. But should it be counted as income? One one hand, it really is more cash in your pocket. On the other hand, it’s not exactly clear how much rent you’d be paying if you didn’t own your home.

A third question concerns corporate retained earnings. Suppose I own a company that makes some profit, and I’d like to take that profit out. But because dividend and capital gains taxes are very high, I have the company keep the money and invest it for me instead of withdrawing it, and I wait for tax rates to go down so I can take the money out and spend it. Does that money count as my income, or not?

There are a bunch more questions like this. And the more you read Piketty et al.’s papers and Auten and Splinter’s papers, the more you realize that the former always choose the interpretation that maximizes inequality, while the latter always choose the interpretation that minimizes inequality. The teams seem very committed to their narratives; Piketty thundered on Twitter that “inequality denial is as dangerous as climate denial.” (Note: No, it is not.)

It seems like a reasonable conclusion is that the truth — to the degree that a single objective “truth” even exists here — is somewhere in the middle. Some of Auten and Splinter’s choices seem reasonable, while others seem less reasonable — imputed rent is pretty clearly a form of income, but Income inequality went up from around 1980 to 2010, but probably less than Piketty and his co-authors think. It’s a problem, but not as big of a problem as the loudest voices would have us believe. This was the general conclusion of the other research teams that looked at income inequality back in the 2010s, and I think it’s the most reasonable.

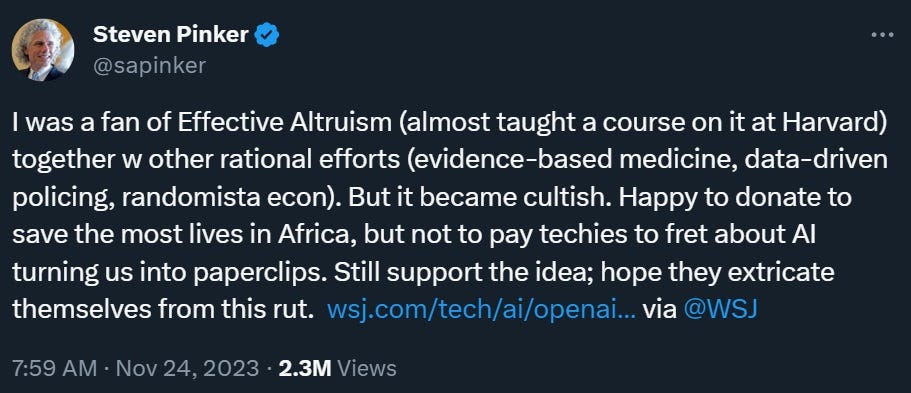

I agree that EA is worth rescuing from some of its high-profile advocates, but I'm still worried about being turned into a paperclip.

(Steven Pinker not being worried makes me worry more, because he's reliably wrong about everything outside his area of expertise. I think he and Richard Dawkins must have made some sort of pact.)

re: japan, i still can never really understand economic reports and analysis of japan’s economy. i’ve been visiting japan for the last 40 years and all i see is advancements everywhere and is still the most futuristic place til this day in addition to social stability, social welfare, and overall widespread wealth like ive never seen. you will never ever see distressed people walking around like zombies fiening for their vice of choice on the streets, it’s just not there. what am i missing?