Don't be a decel

Technological progress must be harnessed, not fought

“Decel” is a derogatory slang word used by the e/acc community. It’s short for “decelerationist”, meaning someone who wants to slow down technological progress. Most decels probably wouldn’t explicitly think of themselves this way, but their attitudes and beliefs end up working in that direction.

For example, consider vaccines. This week, the Nobel Prize in Medicine went to Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, who invented mRNA vaccines. In addition to saving millions of lives worldwide from Covid so far, the technology Karikó and Weissman invented is now being used to create vaccines against everything from pancreatic cancer to malaria. Pancreatic cancer, remember, is a silent killer — so hard to detect that by the time you know you have it, you’re probably already dead. Malaria, meanwhile, is one of humanity’s most destructive endemic diseases, killing hundreds of thousands worldwide every year.

This is an incredible triumph for human science and technology — not just for the researchers who created the vaccines, but for the institutions that supported their work. Those include the NIH that funded the research, as well as the venture capitalists who made a far-sighted bet on companies like Moderna and BioNTech. It includes the Trump administration’s Operation Warp Speed, which managed to develop a novel vaccine in record time, proving that mRNA vaccines are useful and providing a model for future public-private cooperation. And it includes the whole chain of manufacturers who were able to mass-manufacture mRNA vaccines at incredible scale.

In the past, this is the kind of triumph that would have inspired an outpouring of national gratitude and pride, as it did when the polio vaccine was developed.

In the America of the 2020s, however, the achievement has been met with an outpouring of toxic politics. Opposition to Covid vaccines became widespread on the political Right — a third of Republicans say they aren’t vaccinated, 57% of Republicans who got the shot now say they regret it. Online, the antivax movement has developed into a popular subculture, developing an alternative media ecosystem and a whole galaxy of dubious theories and facts.

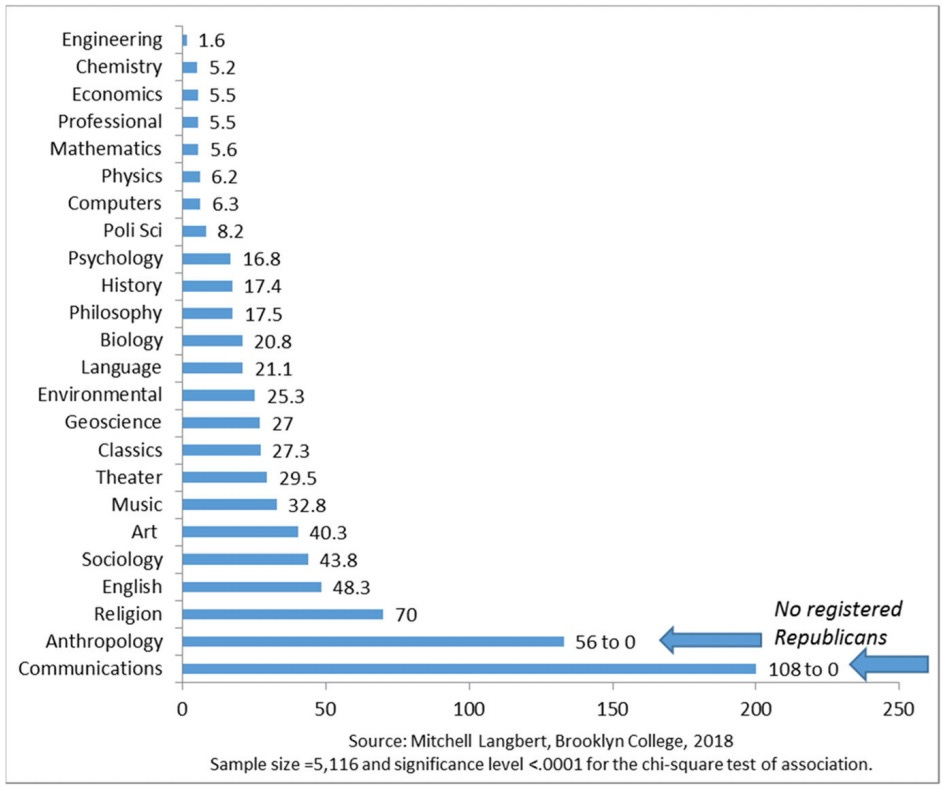

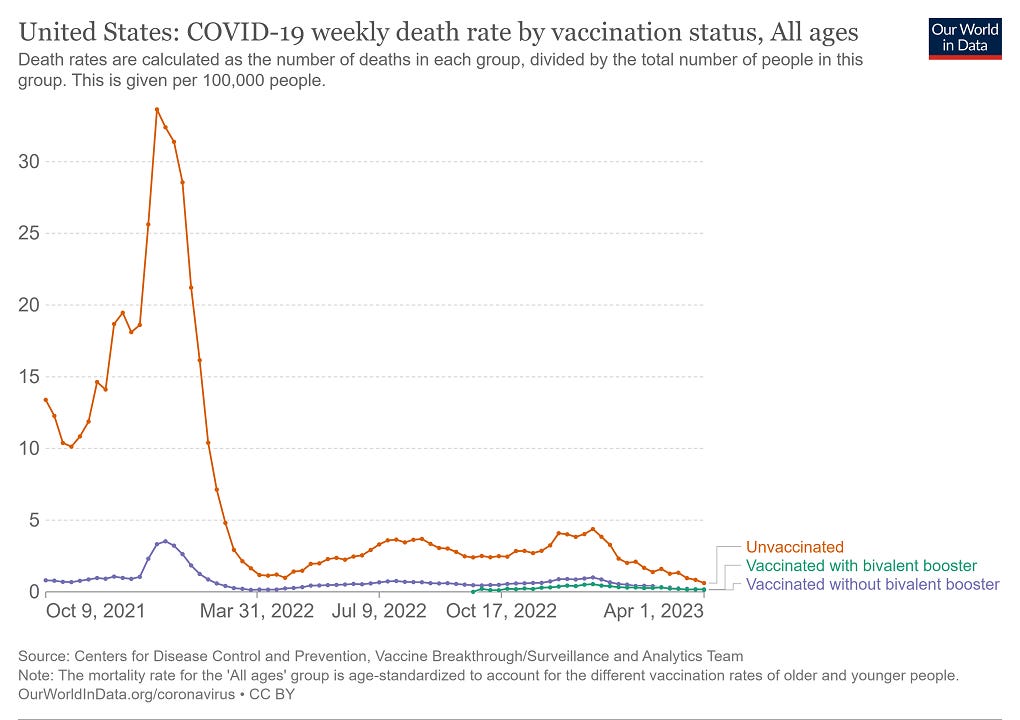

The antivaxxers are, of course, completely wrong, and so obviously wrong that they present a serious challenge to the whole notion of a marketplace of ideas. Claims that vaccines were ineffective in saving lives from Covid have been falsified by a large number of careful scientific studies, and you can run regressions on your own to verify this, but all you really need to do in order to know that Covid vaccines worked is glance at some simple statistics:

The graphs look the same in Switzerland. The graphs look the same everywhere data has been collected. The vaccines worked.

Antivaxxers also claim massive health risks from Covid vaccines. But while any vaccine carries some risk — a good friend of mine went into anaphylactic shock from a Covid shot, and had to go to the emergency room — the idea that these risks are commonplace is just highly improbable. Most of the human beings on the planet have received a Covid vaccine, and there is no great worldwide epidemic of myocarditis or any other serious side effect.

Now, this doesn’t mean there was nothing to criticize in the way vaccination policy and messaging were handled in the U.S. The effectiveness of the mRNA vaccines developed against the original virus definitely decreased when the virus mutated, making initial reports of near-100% effectiveness look overly optimistic. And it’s perfectly legitimate to question or even denounce the use of vaccine mandates in a case where a vaccine doesn’t provide much protection against viral transmission, only against hospitalization. It’s also perfectly legitimate to argue that the way the vaccines were rushed through the FDA’s trial process set a bad precedent.

If antivaxxers had limited their messaging to criticisms like these, they would have had a reasonable case. Instead, they did not. They developed a vast ecosystem of quack theories, folk knowledge, and misinterpreted or even falsified “facts”, and they made their case primarily on social media with a neverending torrent of invective, memes, and hysteria. This is the exact opposite of skepticism; it seeks not to test the claims of science, but to dogmatically denounce those claims by any means necessary.

And it worked. The antivaxxers succeeded in making this amazing technological breakthrough into just another partisan wedge issue and ideological litmus test. It seems almost certain that this campaign against mRNA vaccines will now be carried forward, applied to the new vaccines against pancreatic cancer and other diseases.

This is a fundamentally decelerationist movement. If partisan pressure campaigns leveraging superstition to stoke antipathy to a new invention aren’t an example of a movement against technological progress, I don’t know what is.

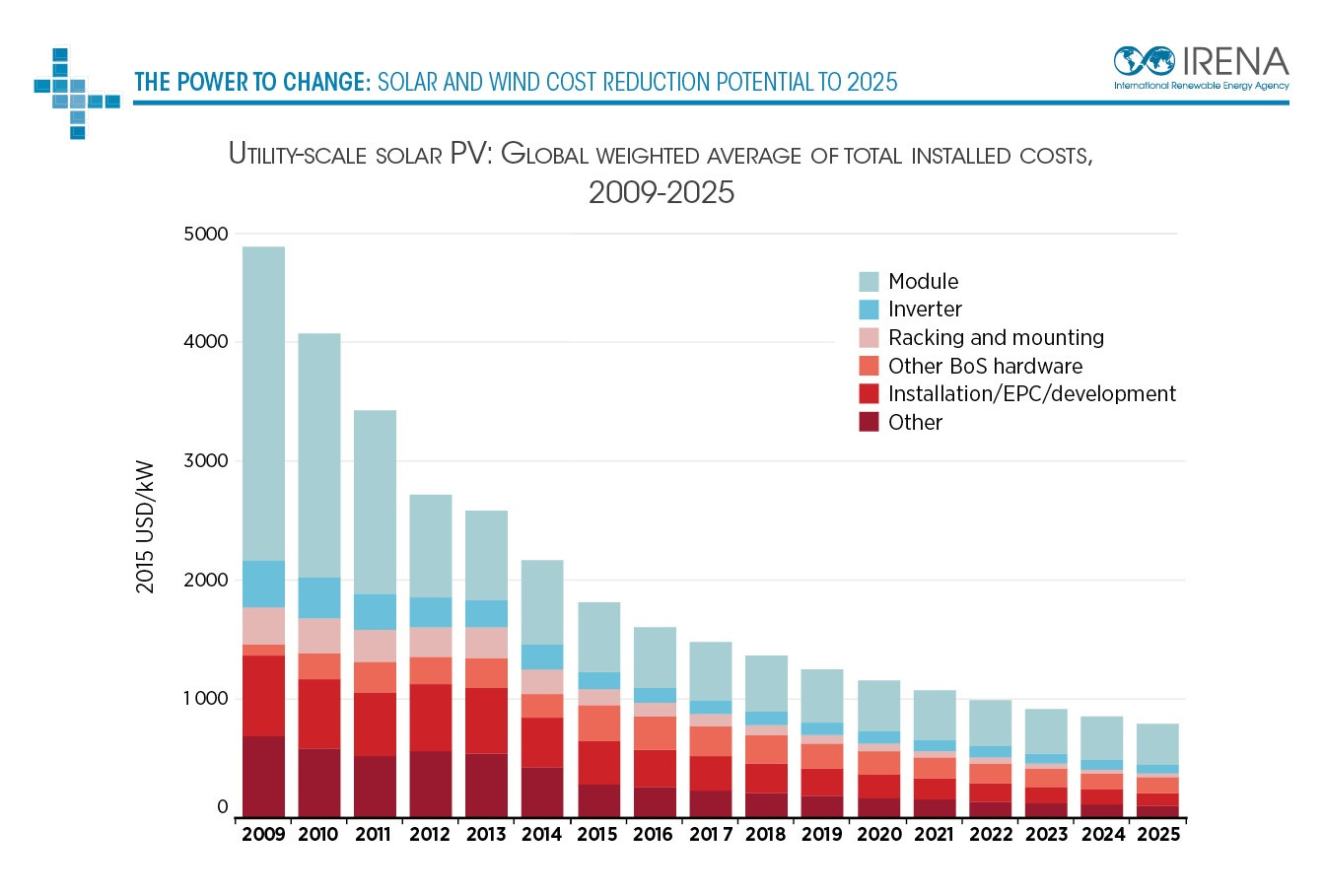

But it’s not the only such movement roiling American society in the 2020s. The opposition to solar power is another. Over the last few decades, solar panel prices have come down by an absolutely incredible amount:

Total installation costs have come down by a huge factor as well:

This is an utter triumph for humanity, offering the promise of cheap abundant electricity that also happens to be carbon-free. It’s a triumph for the research agencies that funded solar’s development through the long decades when it wasn’t economically viable, and for the private companies who eventually took over scaled the technology up. We should be having parades for solar power in the streets.

And indeed, most Americans support rapid development of solar power. But as with mRNA vaccines, there’s a rabid online anti-solar movement that will quickly jump down your throat on social media if you ever praise this technological triumph. They will remind you ad infinitum that solar is intermittent, despite the fact that energy analysts know this very well and incorporate the cost of storage and peaker plants into their calculations. They will repeat (without evidence) that solar is kept afloat only by subsidies, ignoring the fact that poor countries — who can hardly afford subsidies and are not swayed by environmental activists like Greta Thunberg — are adopting solar power at a breakneck pace. And so on; arguing with them, like arguing with antivaxxers, merely wastes minutes of your lifespan. Their conviction is borne of faith.

And to some degree, it’s working. Though perhaps not as strongly as with vaccines, solar power has been turned into a partisan wedge issue. Republicans in Texas, the state that has been the most aggressive about rolling out solar power and which has benefitted from it the most, are now trying to spend government money to support fossil fuel plants to prevent them from being outcompeted by cheap solar.

That is decelerationist. Energy technology is arguably the most important kind of technology that humans create, since everything else we do is downstream of our ability to harness energy. The solar power breakthrough is truly epochal — for the first time since the development of coal power itself, technology has given the world a new, cheaper way to make electricity. It’s something we should be striving to accelerate, not inhibit. The anti-solar movement of the 2020s is reminiscent of the anti-nuclear movement of the 1970s — perhaps the most successful decel movement of modern times.

Then there’s the pushback against AI. Although some very “woke” people are still trying to denounce AI as fundamentally racist, and although a few online “rationalists” are still screaming that Skynet is going to emerge and kill us all, the main fear of AI is that it will take humans’ jobs and make us obsolete. This fear has become essentially ubiquitous in public discussions of the technology. Unlike the antivax and anti-solar movements, the fear of AI is not especially partisan — Republicans are a bit more likely than Democrats to harbor negative feelings about AI, but not by much.

In general, it seems like there’s no field of technological progress that isn’t opposed by a substantial contingent of Americans. Sure, people don’t know much yet about progress in materials science or neuroscience, but it seems likely that if they were getting a lot of press, they’d be experiencing pushbacks too. The U.S. as a whole is not yet a decel nation, but we have far more decels than is healthy.

Why? The most obvious hypothesis is that American society has just been through a period of unrest, where existing social relations were challenged and disrupted. The social conflicts of the 2010s created a deep sense of unease throughout the U.S., in which no one is quite sure whether their country really belongs to them, or how they ought to act around their fellow countrymen, or how they can secure their jobs and social positions. In such a climate, it’s natural to resist any form of change — to view technological progress as just one more thing that makes our lives uncertain. Recall that the original Luddite movement coincided with the revolutionary fervor that was sweeping Europe in the early 1800s. Decel movements may simply be a way of crying “Stop the bus, we want to get off!”.

An era of unrest also provides resentful people with an opportunity to attack those with higher status than themselves. On the political Left, anti-tech sentiment has been directed mainly at “tech bros”, venture capitalists, and founders of tech companies, suggesting status anxiety among downwardly-mobile educated people. On the Right, the resentment is directed more toward scientists. Education polarization means that the higher you climb up the academic ladder in America, the more progressive you’re likely to be. When you reach the professoriate, the difference becomes extreme; conservatives regularly complain about the imbalance.

In an era when scientists lean so strongly to the left, the bitter partisan divide in American society makes it basically inevitable that conservatives will entertain suspicions about a scientific establishment that tells them what’s good for them. In a more unified era, those conservatives might not mind, just as progressives might not mind tech founders getting rich. But in the 2020s, it gives them one more reason to panic, because it means the hands controlling the levers of technological progress belong to their political enemies. This explains the trend of right-wing autodidacts constantly searching for a “truth” that the ivory tower has covered up.

Hopefully the decel trend will wane if and when it becomes apparent that unrest in America has passed its peak. But in the early 2020s, it’s still going strong, and it’s something we need to remember to push against. Eras of division and unrest are the exact time when it’s most important to remind ourselves that over the broad sweep of history, technology is what allows us to live in material comfort, free of disease and other natural threats. It is a force to be harnessed, not fought. And yet progress is never inevitable or automatic; it depends on a favorable institutional context. It depends on government science funding, on private capital, on big business and small business, and very often on public-private partnerships.

And most of all, it depends on a populace that believes that increasing humanity’s power over our world will make tomorrow better than today. The more that hope in our technological future is able to transcend partisan cleavages, online subcultures, and mass ennui, the faster we will move on to the next, better chapter in our history.

Accelerate.

As you ought to know, the people warning about AI posing a risk of human extinction are not "a few online rationalists" but rather a lot of computer scientists and engineers, because the arguments are solid and the counterarguments unconvincing. https://www.safe.ai/statement-on-ai-risk

I agree with you on most kinds of technological progress, but AI is different.

I would add that all of the “reasonable“ critiques of vax rollout you just laid out were, at the time, considered straight up anti-VAX statements. Meaning a lot of the anti-VAX “invective” was actually fueled by a total mainstream unwillingness to have a nuanced conversation, which refusal presented itself as rightly suspect, which, then further fueled suspicions.