At least five interesting things: Red Tape edition (#57)

NEPA; Carter's deregulations; targeted tariffs; YIMBY news; greedflation; a bad viral chart; Acemoglu on H-1bs

The general theme of this week’s roundup is red tape and regulation. These issues are moving to the forefront of the U.S. policy discussion — not just because of the election of Trump, but because people on both sides of the aisle seem to be realizing that the U.S. severely hobbled itself in the 1970s. Now we’re digging out of that hole, and it’s going to be a long, difficult, painful process. But the best time to get started is today.

First, podcasts. I have two episodes of Econ 102 this week. Both are sort of grab-bags of assorted topics:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. NEPA is a millstone around the neck of the United States

In my last post, I talked about how NEPA and similar state laws have held back the kind of forest management that might have prevented the horrific L.A. wildfires. That’s only one example of how environmental review laws — which allow NIMBYs to sue any government-related development project and force it to do years of onerous, often pointless paperwork — represent a millstone dragging down the entire country.

Thomas Hochman, writer of the blog Green Tape, has a great post assembling various facts and statistics showing just how bad NEPA really is:

Here are a few excerpts from his list of bullet points:

Average [environmental impact statement] preparation time is 4.2 years as of 2022

Average review time grew from 3.4 years in 2008 to 4+ years by 2015, increasing by an average of 37 days per year

Average delay from environmental review publication to resolution of legal challenge: 4.2 years

Even a "finding of no significant impact" can take extensive time and documentation (1,200+ pages in one case)

Up to $400 million spent just on regulatory/environmental review process for major projects

Solar projects: 64% litigation rate

72% of NEPA litigation initiated by NGOs

Hochman provides sources for all of these points (and for the many other points in his long list). I have cropped the sources out, but he lists them at the end of his post, and they’re all worth a read. One of the most important sources he cites is the economist Zachary Liscow, who has done heroic work on the problem of infrastructure construction. Here are excerpts from the abstracts of two very recent Liscow papers:

“Getting Infrastructure Built: The Law and Economics of Permitting”

Given the benefits to economic growth and the need to transition to green energy, getting infrastructure built is an urgent issue…[I]n the US, permitting is slow, infrastructure is expensive, and environmental outcomes are not particularly good. I propose a framework for reform with two dimensions: the power of the executive branch to decide and its capacity to plan. After considering reform possibilities, I propose that reforming both dimensions could lead to a possible “green bargain” that benefits efficiency, the environment, and democracy.

“State Capacity for Building Infrastructure”

The high cost of building major infrastructure in the US is a longstanding challenge, but it is not inevitable. This paper highlights three elements of state capacity that underlie the high costs and slow timelines the US faces. The first challenge is personnel: government pay has not kept up with private pay, and the public workforce has not kept up with the workload; public-sector work is instead increasingly privatized, raising costs. The second challenge is procedure: government workers operate under onerous procedures and in a litigation environment that makes construction slow and expensive. The third challenge is a lack of adequate tools, including data systems and long-term planning abilities…Regarding personnel, hiring more government planners and managers, paying them in line with the private sector, and insourcing more planning could help. Regarding procedure, reducing permitting and procurement burdens, promoting faster but more representative public participation, improving coordination, and centralizing certain decisions at the federal level could help. Regarding tools, improving internal data systems and data availability would create a better evidence base, and better long-term planning could improve decisionmaking quality.

Both papers are recommended reading.

And it’s important to remember that although NEPA is a procedural requirement — it lets you sue to block development regardless of whether the project you’re suing is in compliance with environmental laws — it’s rationale is ultimately based on environmental regulations like the Endangered Species Act. Although I think most of those regulations are good overall, many of them have been weaponized by bad-faith actors to block development on ideological grounds. For example, the New York Times had a recent story about how some researchers basically invented a new species in order to block the construction of a dam back in the 1970s:

[T]he snail darter has haunted Tennessee. It was the endangered species that swam its way to the Supreme Court in a vitriolic battle during the 1970s that temporarily blocked the construction of a dam…On Friday, a team of researchers argued that the fish was a phantom all along.

“There is, technically, no snail darter,” said Thomas Near, curator of ichthyology at the Yale Peabody Museum…Dr. Near, also a professor who leads a fish biology lab at Yale, and his colleagues report in the journal Current Biology that the snail darter, Percina tanasi, is neither a distinct species nor a subspecies. Rather, it is an eastern population of Percina uranidea, known also as the stargazing darter, which is not considered endangered.

Dr. Near contends that early researchers “squinted their eyes a bit” when describing the fish, because it represented a way to fight the Tennessee Valley Authority’s plan to build the Tellico Dam on the Little Tennessee River, about 20 miles southwest of Knoxville.

“I feel it was the first and probably the most famous example of what I would call the ‘conservation species concept,’ where people are going to decide a species should be distinct because it will have a downstream conservation implication,” Dr. Near said.

More state capacity, in the form of bureaucrats who are able to suss out this kind of opportunistic anti-development misinformation, is the obvious solution to this problem. Zachary Liscow is right — in order to cut through red tape, you need to empower the people with the scissors. Government is the main actor who gets blocked by NEPA and similar laws, so government needs the ability to slice through those legal barriers and get things done.

2. Carter’s deregulation is relevant today

Jimmy Carter passed away recently. I was pleasantly surprised to see that one of the main reactions to his death — at least in the blogosphere and on social media — was to remember his legacy as a deregulator:

As I wrote back in 2021, Carter did much more deregulation than Ronald Reagan did:

Carter deregulated energy, trucking, airlines, retail banking, and other stuff like beer. Plenty of stuff that Americans take for granted — like the fact that air travel is much cheaper in the U.S. than in Canada — comes from Carter’s deregulatory efforts. In fact, Carter’s bank deregulation might have been instrumental in ending the inflation of the 1970s (along with Carter’s appointment of Paul Volcker to head the Federal Reserve, of course).

Why are people choosing to remember Carter’s deregulatory legacy right now? For a long time, his name was unfairly associated with big government, and when people said nice things about him they generally focused on his human rights work. But right now, deregulation is a hot topic in America — the effort to reindustrialize America and solve the housing shortage is running into big regulatory barriers, and bipartisan consensus will be needed to remove those barriers. People might be choosing to remember Carter as America’s Great Deregulator because they hope that today’s progressives will be able to follow a similar path.

3. Did Trump’s people listen to me about targeted tariffs?

Back in November, I wrote a post explaining why targeted tariffs on specific strategic products are generally effective at blocking imports of those products, but broad tariffs are not very effective at reducing trade deficits:

Basically, there are two reasons: 1) exchange rate adjustment, and 2) intermediate goods. When you do broad tariffs, your country’s currency appreciates against the currency of the country you put tariffs on, partially cancelling out the effect of the tariffs. And when you put tariffs on everything, you block your own manufacturers from being able to import the intermediate goods they need to stay competitive. Targeted tariffs avoid both of these problems — they can succeed because their goal is more modest.

Tyler Cowen picked up my post and endorsed it. Hopefully, people in the Trump administration read Tyler!

Well, whether or not they got the idea from me, there’s some sign that Trump’s people understand that targeted tariffs are more effective than broad ones:

President-elect Donald Trump’s aides are exploring tariff plans that would be applied to every country but only cover critical imports, three people familiar with the matter said — a key shift from his plans during the 2024 presidential campaign.

If implemented, the emerging plans would pare back the most sweeping elements of Trump’s campaign plans…[R]ather than apply tariffs to all imports, the current discussions center on imposing them only on certain sectors deemed critical to national or economic security…

Preliminary discussions have largely focused on several key sectors that the Trump team wants to bring back to the United States, the people said. Those include the defense industrial supply chain (through tariffs on steel, iron, aluminum and copper); critical medical supplies (syringes, needles, vials and pharmaceutical materials); and energy production (batteries, rare earth minerals and even solar panels)[.]

This is good. This is progress.

The next big thing Trump’s people need to understand is that tariffs on friendly countries make it much harder for American companies to compete with their Chinese rivals. I’ll write another post about that soon.

4. This week’s YIMBY news

I’m using these roundups to track the long-term progress of YIMBYism — policy changes, research, and actual real-world results.

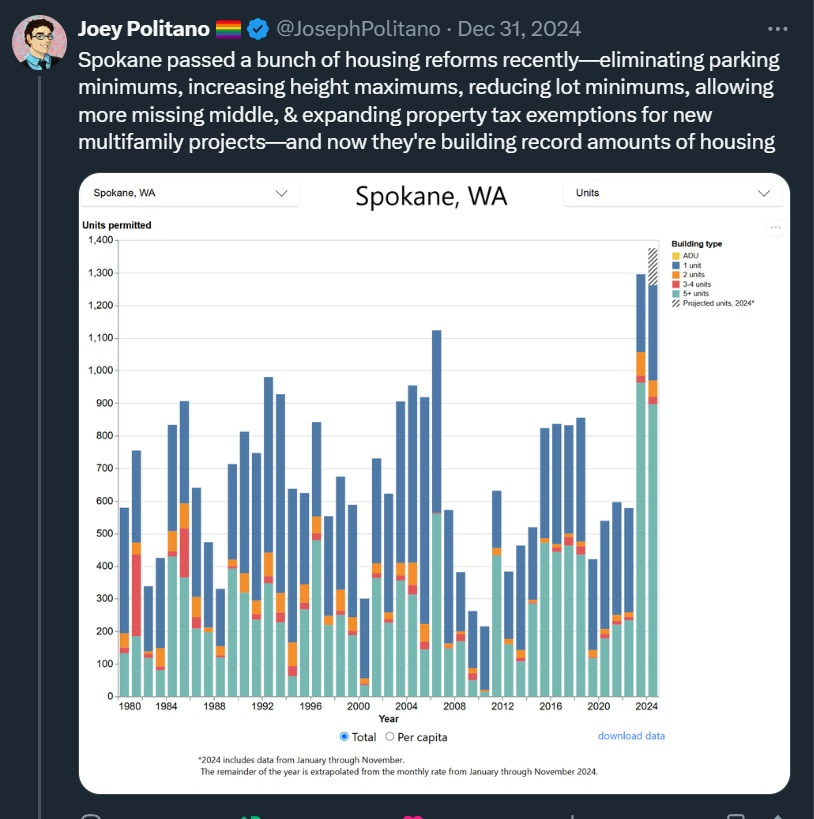

In the “actual real-world results” department, this week we have Spokane, Washington, which has become the latest city to deregulate its way to increased housing abundance:

For reference, here’s a story from late 2023 about Spokane’s deregulatory efforts, back when they were first passed into law. As for what effect this has on rent in the city, it’s too early to tell, and it’s notable that Spokane also enacted rent control around the same time. But at least this should tell us that deregulation can produce a housing construction boom pretty quickly.

On the research side of things, we have a new paper from Andreas Mense, called “The Impact of New Housing Supply on the Distribution of Rents”. Mense evaluates the impact of housing supply by looking at what happens in Germany when weather events delay housing construction. Mense finds that 1% more housing supply decreases rents in a city by 0.19% — not bad! The rent decreases are biggest for lower-quality units, suggesting that poor renters reap the biggest benefits from increased supply. And crucially, the impact of supply is equally large in high-demand markets, thus refuting the left-NIMBY claim that increased supply causes gentrification.

A very pro-YIMBY result. Unsurprising, perhaps, but important nonetheless.

Meanwhile, another very interesting new paper is “Housing and Fertility”, by Fazio et al. Looking at housing lotteries in Brazil, the authors find that homeownership makes people have a lot more kids:

We find that obtaining housing increases the average probability of having a child by 3.8% and the number of children by 3.2%. For 20-25-year-olds, the corresponding effects are 32% and 33%, with no increase in fertility for people above age 40. The lifetime fertility increase for a 20-year old is twice as large from obtaining housing immediately relative to obtaining it at age 30. The increase in fertility is stronger for households in areas with lower quality housing, greater rental expenses relative to income, and those with lower household income and lower female income share. These results suggest that alleviating housing credit and physical space constraints can significantly increase fertility.

It’s not clear whether this result will generalize from Brazil to richer countries with different cultures. But housing abundance is definitely something worth trying, given the global fertility crisis that no one knows how to solve!

5. Greedflation: still not a real thing

The election of Trump pretty much killed any chance of enacting Elizabeth Warren’s progressive economic program. So people have pretty much forgotten about how Warren and a bunch of other progressives tried to blame inflation on opportunistic price gouging by powerful corporations in uncompetitive markets — a story that came to be known as “greedflation”.

There was never much evidence in favor of the greedflation hypothesis. Researchers found that industries with higher markups — indicating more market power — had lower rates of inflation in the post-pandemic period. Various other papers that looked for a link between market power and inflation found nothing.

Anyway, we now have yet another piece of evidence against the “greedflation” idea. In a new paper called “Has corporate greed driven inflation in the European Union? An analysis of the food and beverage industry”, Koppenberg et al. find that companies in the European food industry generally haven’t been passing on higher costs to consumers:

The EU has recently experienced high inflation rates, particularly in food prices. This observation led to claims in the news and by retailers that large food and beverage manufacturers take advantage of high inflation, and increase prices more than necessary (“greedflation”) to compensate for increases in their raw material prices. To test whether this claim is true, we estimate a production function to determine markups of output price over marginal costs for a sample of 88,717 European food and beverage manufactures covering the years 2013–2022. Our results do not support the greedflation hypothesis as markups have decreased over the considered period. In addition, there is a negative correlation between raw material prices and markups which is stronger for large firms, suggesting that these firms cannot be generally accused of taking advantage of high inflation. Our results imply that claimed “greedflation” does not justify additional pro-competitive policies in the food and beverage manufacturing sector.

Here’s a thread by Jack Salmon explaining the paper’s results.

Yes, this result depends on the choice of a production function — in other words, you need an assumption about how different input costs ought to determine the cost of a particular food product. But in general, these production functions are very flexible, and the correlation between markups and input costs across companies isn’t really going to depend on the choice of production function.

So no, there’s still no evidence that greedflation was ever real. The Warren economic program, which never really caught fire with voters, was also often at odds with economic reality. Another example of populism without popularity from the progressive movement, unfortunately.

6. A bad viral chart about faith in democracy

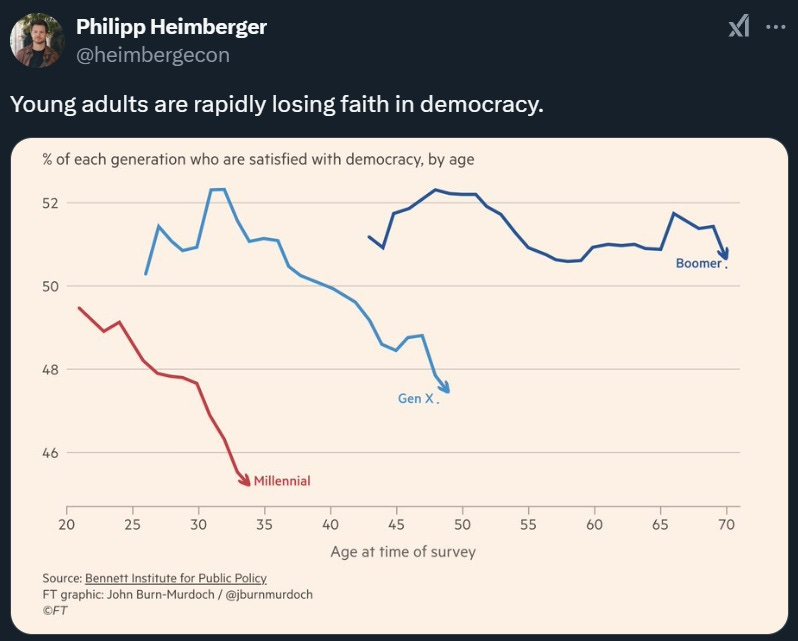

Well folks, it’s time for another episode of “How not to be fooled by viral charts”. The chart this time is from the Financial Times, courtesy of Philip Heimberger:

What’s wrong with this chart? In my original post, I cautioned everyone to check where the y-axis starts:

Another thing you should look out for is where the y-axis starts. Contrary to what some people say, it’s fine to have charts where the y-axis doesn’t start at zero. For example, if you’re graphing a human being’s body temperature, there’s no need to start at zero, because someone would be dead if their body temperature went to 85. Fluctuations of just a degree or two make a big difference in human body temperature, so you want to be able to zoom in and see those fluctuations.

That said, you should pay attention to where the y-axis starts. Don’t just assume it starts at zero!

In the chart above, we can see that the y-axis only goes from about 45% to about 52% — a very small range! And we can see that the generations that are “losing faith in democracy” have only gotten a few percentage points less faithful over the last two decades. Is this a worrying trend? Sure. Does it merit the level of panic that the compressed y-axis creates? I don’t think so.

Another problem with this chart is the arrows on the end of the lines. In a follow-up to my original post, I warned about this misleading form of data presentation:

So when you make charts, think very carefully before putting arrows on the ends of time series. Econometricians and statisticians have a whole lot of ways of estimating the trend of a time series, and as far as I know, none of them involve taking the direction of change between the two most recent data points and assuming that that’s the current trend.

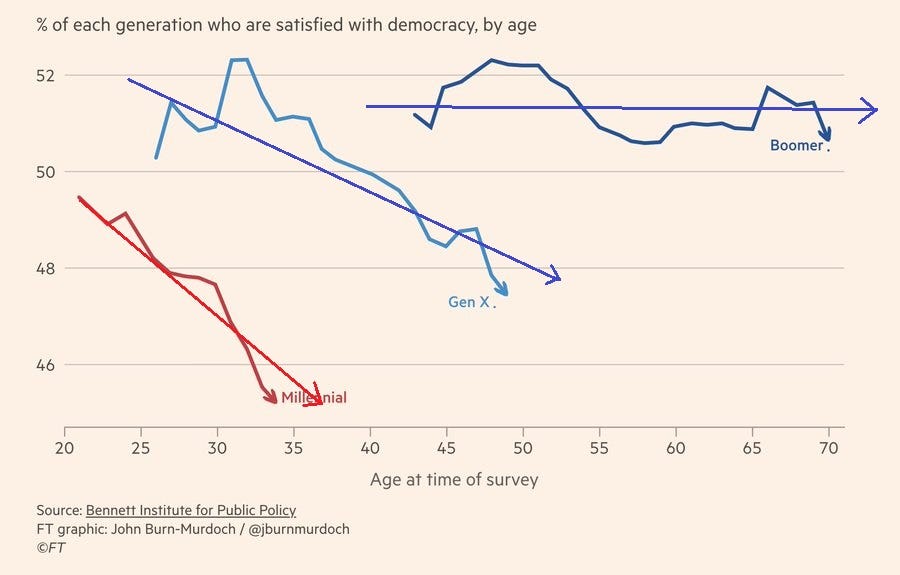

To illustrate this, let’s take the chart from above and draw some rough best-fit trendlines for the three generations:

For Millennials and Gen X, the trendlines roughly match the arrows that the FT drew on the ends of the lines. For the Boomers, they’re utterly different — the arrow shows satisfaction headed straight down, while the trendline over the last few decades is pretty much completely flat. The arrows on the ends of the lines thus give a roughly accurate picture of the trend for the two younger generations, but for the Boomers, the arrow is utterly deceptive, creating the false impression of a collapse when there probably isn’t one.

In other words, this viral chart doesn’t shows a worrying trend, but it doesn’t show that support for democracy is collapsing. The compressed y-axis and the arrows on the ends of the time series create excessive alarmism.

7. What the heck is Daron Acemoglu talking about?, H-1b edition

Daron Acemoglu is the world’s top economist, and I always feel a lot of trepidation when I criticize things he says. But these days he says an awful lot of things that I feel are worth criticizing. His book about the history of technology was full of holes, and when he wrote about AI and productivity he had to arbitrarily ignore parts of his own theoretical model in order to achieve the result he wanted.

Now Acemoglu has jumped into the conversation on H-1bs with a very odd theory about why they’re bad:

One argument I haven’t seen is that sufficiently large flows of skilled immigrants may affect the direction of technology. A general theorem of directed technology is that when the supply of skilled labor increases, technology becomes endogenously more biased towards skilled workers (see, for example, https://academic.oup.com/restud/article/69/4/781/1551628or… https://aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pandp.20231000…).

So one question is whether H1B program has contributed to US technology becoming more and more focused on high-education workers and leaving lower-education workers behind. Possibly not, since there has been a lot of unskilled immigration as well, and other factors may have been more important in the direction of technology (and the evidence does not show a total crowd out overall of innovation by natives, see https://journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/651934…).

Nevertheless, the impact of high-skill immigration on the direction of technology is worth exploring in the future. What this argument suggests more generally is that if the US is going to rely on H1B workers, policymakers should pay consider other adjustments so that US technology and corporate strategies do not leave low-education workers completely behind.

Basically, Acemoglu is arguing that because America is getting a lot of skilled workers through the H-1b program, we’re focusing on inventing the kind of technologies that high-skilled people can use — for example, software that’s easy for smart people to use but hard for normal folks to master.

That’s a very odd argument, for several reasons. First of all, there’s no real evidence for it — Acemoglu simply cites two theory papers that he wrote, in which he assumes that this kind of thing could happen.

On top of that, the numbers here are just totally implausible. There are only about 600,000 H-1b workers in the U.S., compared to more than 34 million Americans who work in STEM occupations. Annual H-1b visas are capped at 85,000, while the U.S. produces over 750,000 STEM degrees domestically per year. Even if Acemoglu’s assumptions bear any resemblance to the way technological innovation is actually determined, it seems highly unlikely that the H-1b program is a major factor relative to America’s own education system.

In fact, if Acemoglu is right that producing more STEM workers increases inequality, the obvious policy implication is that America should stop educating so many STEM workers. That’s obviously a bad idea. But it also contradicts Acemoglu’s own very next point, in which he argues that H-1bs are bad because they reduce U.S. STEM education!

Second point – political economy of education: The following argument at first appears watertight: the US has a need for skilled STEM workers, for example in the tech industry, and is not currently able to produce this supply itself. Hence, it seems innocuous and generally beneficial to make up this shortage via the H1B program.

What this argument ignores is the following, however: if it weren’t for the H1B program, the pressure on US institutions to improve the quality of secondary education and the supply of STEM workers would have been much stronger. Put differently, the current system may have made the economic (and political and intellectual) elites care less about the failure of the US education system. (The argument that the elites would like the education system to produce workers that their businesses need goes back to Sam Bowles and Herb Gintis’s classic Schooling in Capitalist America: https://amazon.com/Schooling-Capitalist-America-Educational-Contradictions/dp/0465097189…).

So Acemoglu wants fewer H-1bs so we have more political pressure for domestic STEM education. But he also thinks having more STEM workers increases inequality, by causing inventors to focus on technologies that help STEM workers instead of normal folks! These two arguments clearly contradict each other.

In other words, it seems like Acemoglu is grasping for reasons to support a desired policy conclusion, without noticing that those arguments are inconsistent. I suppose “finding reasons to support a desired policy conclusion” is kind of par for the course in the world of macroeconomic theory, but it’s not a great way to steer national policy.

I feel like I’ve read 100 articles about the horrors of NEPA and none of them ever call for just repealing it. Anyone know why?

“The first challenge is personnel: government pay has not kept up with private pay, and the public workforce has not kept up with the workload; public-sector work is instead increasingly privatized, raising costs.’

I’m a living example of this. I retired after 29 years came back as a consultant (because they were hamstrung by the legislature to hire permanent replacement positions), and I’m making 50% more than when I left. And if you’re wondering why I stayed 29 years at crap wages, I really liked my job and it came with a secure pension, like no other private engineering firm offered.