At least five interesting things for your weekend (#49)

Degrowth, real and imagined; 90s taxes; China's banks; CHIPS Act bureaucrats; YIMBY education; the slacker era

I’m pretty busy right now, finishing up a book draft, going to some weddings, and getting over a nasty infection, so I’m afraid this week’s issue of “at least five interesting things” will only have…six things. Don’t worry, none of them are about the election.

Anyway, here’s an episode of Econ 102, where I answer a bunch of questions about a bunch of stuff:

I really do like the Q&A format. Did you know I did extemporaneous speaking in high school?

OK, on to this week’s list of interesting things:

1. Degrowth in theory (silly) vs. degrowth in practice (terrifying)

“And when you look down, you'll see tiny figures pounding corn, laying strips of venison on the empty car pool lane of some abandoned superhighway.” — Tyler Durden

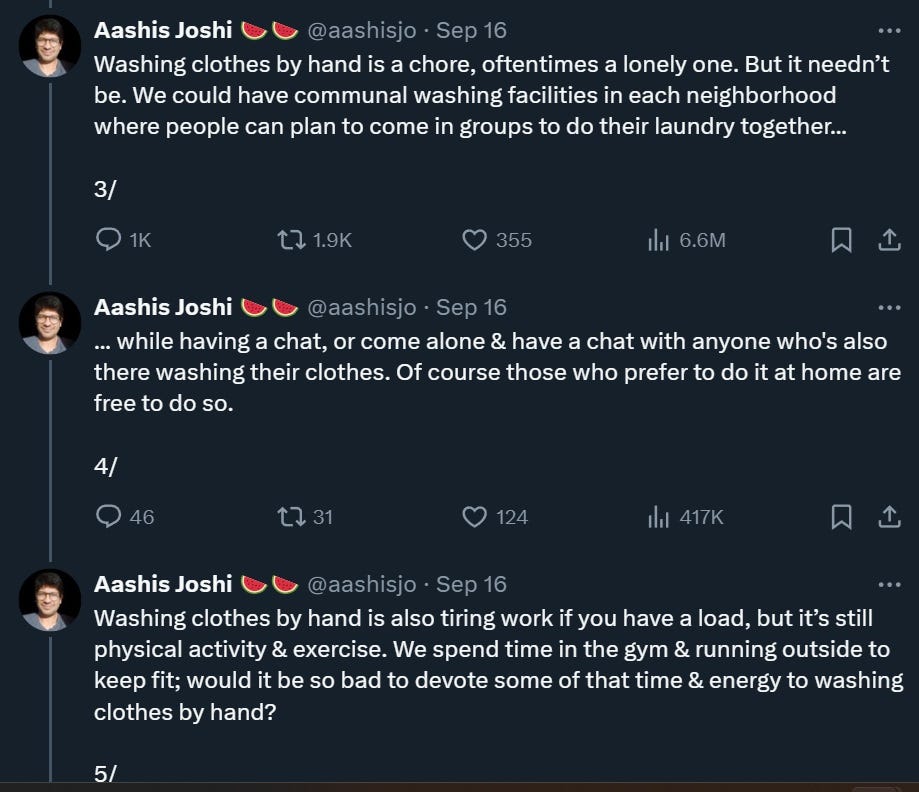

A lot of people on X took a quick break from election screaming to make fun of a pretty ridiculous thread by Dutch PhD student Aashis Joshi, who wrote a long and ridiculous thread arguing that people should give up their modern appliance. The funniest part was when Joshi argued that washing clothes by hand, instead of using a machine, would create community and provide good exercise:

I could write a long and indignant rebuttal of this silliness, but fortunately, Jeremiah Johnson of the blog Infinite Scroll has already done so. Johnson points out that washing clothes by hand is an awful, dangerous life-sucking experience that Aashis Joshi and degrowthers like him would never voluntarily do:

Let’s state something obvious. Few, bordering on none, of these degrowth people will ever voluntarily give up the things they claim that all of society should give up. I guarantee you that Aashis Joshi does not spend 20 hours a week washing his family’s clothes by hand. Nobody who has ever washed clothes by hand would ever, ever voluntarily do so if given the option of a washing machine. If you’ve never run across it, Robert Caro’s description of what laundry was like for women in Texas hill country in the 1930s is one of the most profound things I’ve ever read about economic progress. Laundry was backbreaking, dangerous, brutal work. Women’s bodies grew prematurely stooped from hauling the necessary water. The lye soap they used burned the skin off their hands, and if that didn’t the physical chunks of iron they heated over open flames for ironing would…

Aashis Joshi…does not actually believe that people are morally obligated to wash their clothes without a washing machine because of climate change….We can tell this because he’s not doing it himself…Ultimately, what he’s doing is LARPing.

That sounds accurate to me. In the 1970s, a number of people in the developed world tried to get back to the land by moving to “hippie” communes. It was a good try, though almost all were eventually abandoned or became businesses. In contrast, the neo-pastoralists have no desire to actually practice what they preach — they want to go online and tell you to go be a premodern peasant, while they themselves collect a university salary for hectoring you. They will then spend that salary on laundry detergent and fabric softener.

But if degrowth as an academic theory is destined for the compost pile of history, degrowth as actual practice is far too common. Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes, and Sam Bowman have a long and excellent post detailing many of the ways in which the United Kingdom blocks investments in housing, infrastructure, and energy. Some excerpts:

Between 2004 and 2021, before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the industrial price of energy [in the UK] tripled in nominal terms, or doubled relative to consumer prices…With almost identical population sizes, the UK has under 30 million homes, while France has around 37 million…Per capita electricity generation in the UK is just two thirds of what it is in France…Tram projects in Britain are two and a half times more expensive than French projects on a per mile basis…Britain has not built a new reservoir since 1992…Despite huge and rising demand, Heathrow annual flight numbers have been almost completely flat since 2000…The planning documentation for the Lower Thames Crossing, a proposed tunnel under the Thames [cost] more than twice as much as it cost in Norway to actually build the longest road tunnel in the world…

These are not just disconnected observations. They highlight the most important economic fact about modern Britain: that it is difficult to build almost anything, anywhere.

Southwood et al. then go on to detail many of the ways in which the UK’s legal and institutional framework prevents housing, infrastructure, and energy from being built. Many American readers will recognize a lot of the same problems that plague our own country — NIMBYism, cumbersome environmental review procedures, low state capacity, outsourcing to consultants, and so on. The Anglosphere countries share many of the same dysfunctions. But the UK also has various other problems that the U.S. generally doesn’t have, such as hard government limits on urban sprawl combined with height restrictions that prevent density. America and Britain both make growth very hard; Britain often simply forbids it.

Now, I wouldn’t take Southwood et al.’s pronouncements as gospel. They do get some things wrong — for example, they place too much of the blame for the UK’s high electricity costs on the intermittency of wind power,1 when in fact the far bigger problem is that the UK’s total electricity production has collapsed by a quarter. In energy, as in housing, the UK’s poverty comes partly by decree — a combination of carbon taxes and government mandates forced a phaseout of coal and a squeeze on natural gas, even as NIMBYism prevented any alternative from quickly emerging.

The result of all these British policies is real, actual degrowth — not the neo-pastoralist fantasies of faux-environmentalist postdocs, but concrete policies designed to placate the citizenry by preserving the built environment of the recent past. Real degrowth isn’t a yearning for the 1700s, but for the 1970s. Change is scary, and ensuring people that the government will prevent change is what I call a “stasis subsidy” — a promise that looks cheap in the present because it incurs no fiscal costs, but creates huge economic costs down the road. The UK is paying those costs now.

2. 90s taxes weren’t so bad, were they?

America needs austerity. Since 2000, we’ve borrowed a ton, basically betting that interest rates could stay low forever. That bet didn’t work out, and interest costs are now soaring, so our government needs to cut back. Given both historical precedent and political necessity, that austerity is going to have to come from a combination of spending cuts and tax hikes.

Last time I talked about spending cuts; today let’s talk about the tax hikes. In the 2000s, when we briefly defeated the deficit, taxes were almost 20% of our GDP. Today they’ve been cut to just over 16% of GDP:

For reference, U.S. GDP is about $28.8 trillion, so this means a drop of about a trillion dollars a year in tax revenue relative to the tax rates at the turn of the century.

The late 90s were a great time for economic activity, so it makes sense that if we return taxes to late 90s levels, it probably won’t hurt the economy much. In fact, the economists Owen Zidar and Eric Zwick suggest exactly this, in a recent white paper entitled “A modest tax reform proposal to roll back federal tax policy to 1997”.

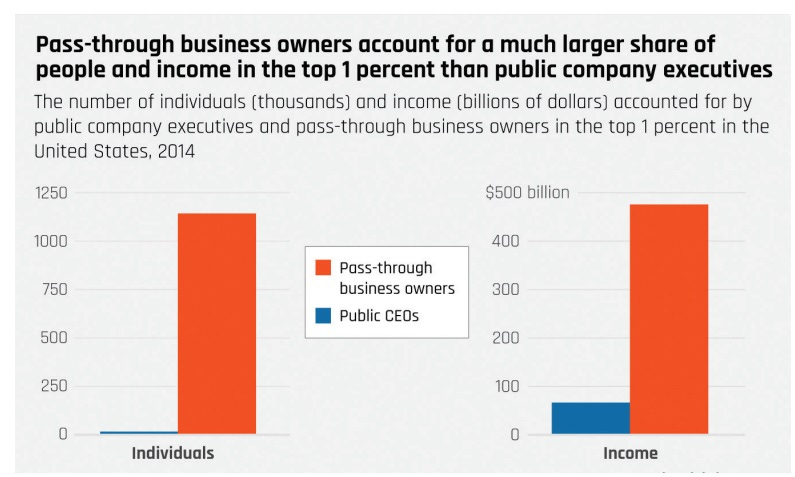

Zidar and Zwick, along with co-authors Danny Yagan and Matthew Smith, wrote a paper in 2019 in which they found that most American rich people own pass-through businesses like S-corporations or LLCs. Most discussions about rich people in America focus either on corporate CEOs or on the billionaire founders of large public companies. But Zidar and Zwick show that most rich people just own their own pass-through businesses:

If you want to tax the rich, you should tax pass-through business income.2

The first thing to do — and Zidar and Zwick’s first proposal — is to reverse Trump’s tax cuts (which are officially set to expire anyway). Trump cut taxes on pass-through businesses in 2017, along with cutting corporate tax rates overall. Zidar and Zwick (along with Smith and Gabriel Chodrow-Reich) recently wrote a paper finding that this tax cut boosted business investment, but only by a small amount. So they figure this is a safe tax hike.

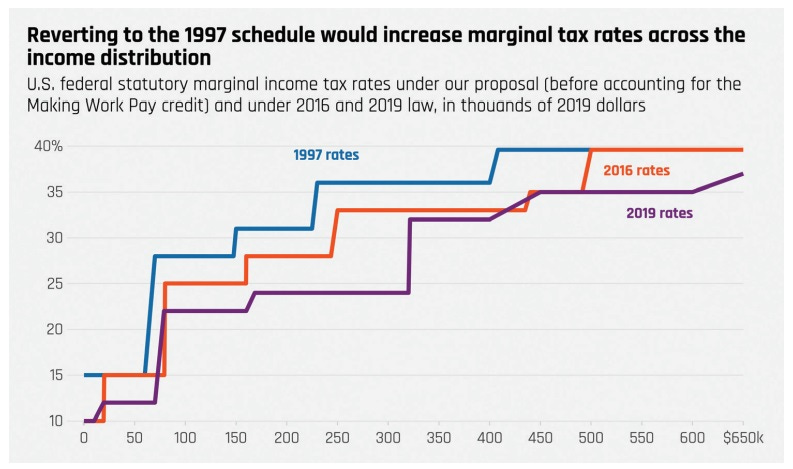

Zidar and Zwick also propose taking capital gains taxes, dividend taxes, and estate taxes back to 1997 levels, as well as a few other “back to 1997” tweaks. They also propose raising both the personal income tax rate and the corporate tax rate back to what they were under Clinton, while adjusting the brackets for inflation.

Altogether, they estimate that this would raise around $470 billion a year — enough to take us about halfway back to 2000 levels of taxation. That wouldn’t solve the deficit problem completely — the deficit is now at $1.9 trillion — but it would be substantial. A writeup of their proposal by Neil Weinberg shows that most of this new revenue would come from raising the personal and corporate income tax rates.

It’s important to realize that this would be a tax hike on the middle class as well as the rich. Here’s a diagram of how their proposal would change tax rates:

Naturally the higher taxes on low-income people wouldn’t make it into the final proposal, but this diagram shows something important: if we’re going to contain the deficit, all of America, not just the wealthy, have to pitch in. That might be a tough sell to the American people, who got used to having their cake and eating it too during the era of ultra-low interest rates. But that world of freebies is gone now.

3. China’s financial woes

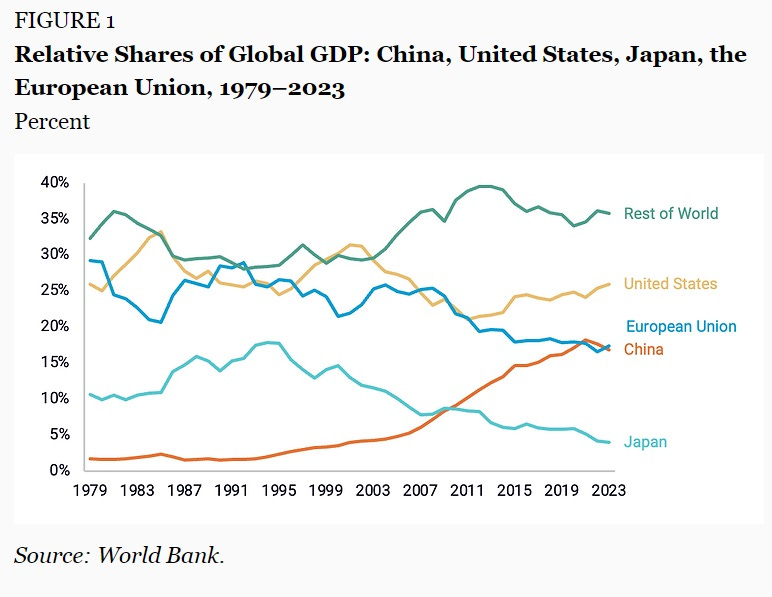

Logan Wright of the Rhodium Group has a long post in which he argues that China’s share of the global economy has peaked. Here’s the key chart:

It’s interesting to note that if he’s right, China’s share of the world economy will have peaked at around 18% — just about the same level that Japan, which has less than 1/10 of China’s population, attained at its peak in 1994. Part of this is that Japan got really rich before it started its relative decline — it was about as rich as the U.S. back in the early 90s, while China is still only about 30% as rich as the U.S. Part of it is that China’s exchange rate is a more undervalued now than Japan’s was back then. But part of it is that the rest of the world has grown a lot since the 90s, making it harder for either China or any other country to maintain its relative position (though the U.S. is doing OK).

It’s questionable whether “share of global nominal GDP” is the right measure for assessing a country’s rise and relative decline. This number is important because it measures purchasing power on world markets — the higher your share of global nominal GDP, the more of the world’s tradable resources you can afford to buy. But other than that, there’s not much significance to this number — if you want to measure a country’s ability to turn economic might into military force, you’d want to use GDP adjusted for military purchasing power instead.

But anyway, Wright argues that China isn’t going to see its share of global GDP go back up anytime soon. The main reason he cites is an overhang of bad bank debts from the real estate boom and bust. Basically, he thinks that the idea that China is a “unitary state” — that local governments and banks seamlessly implement the will of the central government — is false, and that banks are looking out for themselves instead of obeying diktats from Beijing. These banks, he says, are scared to lend, because they need to preserve their capital to prevent themselves from going out of business.

This seems like a plausible reading of China’s political economy — at least, more plausible than the China boosters’ typical assertion that every bank in the country is a perfect extension of Xi Jinping’s personal will. Chinese banks know that Xi and the central government are perfectly willing to let local businesses fail — it happens all the time. So it makes sense for insolvent banks to keep lending money to their typical borrowers (state-owned enterprises, local government financing vehicles, etc.) at incredibly cheap rates, to pretend that they don’t have bad debt problems. Because Chinese banks are limited in the amount of loans they can make, this sucks up capital from new and more productive companies — basically, a variant of Japan’s “zombie” problem from the 1990s.

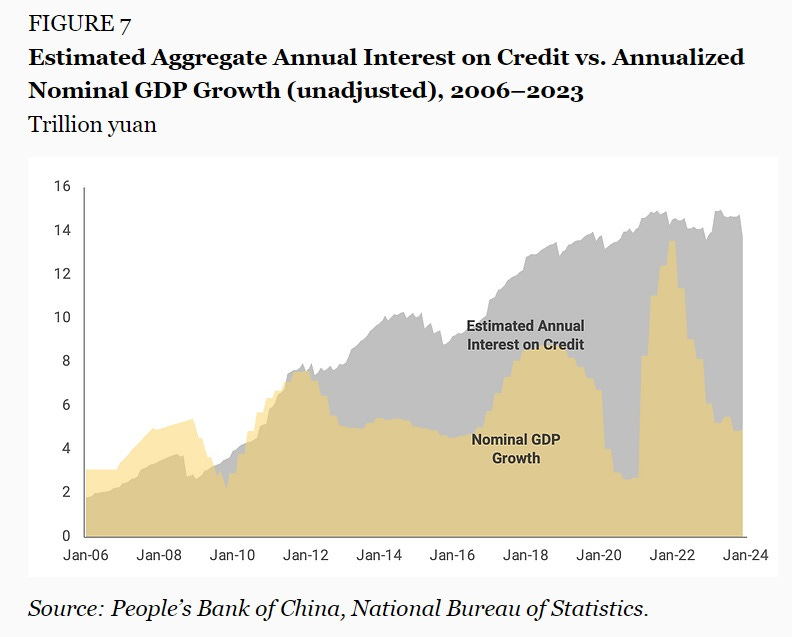

According to Wright, all that bad debt is going to make China’s banks reluctant to lend, unless and until China’s central government bails out its banks. I completely agree. This is what allowed the U.S. to return to robust growth only 5 years after the 2008 real estate crash. China is now almost 3 years out from the collapse of Evergrande — time flies, eh? — and it still hasn’t done a comprehensive bailout of its financial system. Meanwhile, as Wright shows, the problem is still getting worse — existing debts are accruing interest at a rate that’s faster than overall economic growth, which means an ever-increasing burden on the banks:

Essentially, Xi Jinping is betting that his industrial policy — throwing an unprecedented amount of money at companies — will raise productivity growth by such a tremendous amount that this equation will reverse, and China will be able to grow out of its debts. Wright is rightfully skeptical of this. The amount of productivity growth required would be absolutely unprecedented — if it turned out that growth were that easy to supercharge simply by throwing government money at manufacturing companies, it would be the most important revolution in economic policymaking in human history.

Instead, if I were in charge of China, I would just bail out the banks.

4. The CHIPS Act got some very good people

It’s very long, but I strongly recommend checking out Doug O’Laughlin’s interview of Dan Kim and Hassan Khan, two of the federal bureaucrats tasked with implementing the CHIPS Act:

America has committed a huge amount of money, and invested its hopes for national security, in this industrial policy program. But there’s no magic button you can press that says “make semiconductor industry strong”. Government has to learn how to do it — it has to try things, make mistakes, observe what went wrong, and try new things. There are always unexpected bottlenecks, and things that get easier with practice, and innovative solutions.

Several things are critical for this process. First, you need policy continuity — you can’t just have the other party upend and destroy the whole policy as soon as they get into office. Second, you need personnel continuity — the lessons of past successes and failures are too complex to be written down, so they’re embodied in the actual people who run the programs. And finally, you need personnel quality — you need to have public servants who are both intelligent and highly dedicated to the work.

O’Laughlin’s interview with Kim and Khan makes it clear that we at least have the latter. Their open-mindedness, reasonability, respect for the importance of the private sector, and obvious sense of dedication should force anyone who imagines American bureaucrats as stuffy, rule-obsessed martinets to do a deep rethink.

The interview makes it clear that Kim and Khan come from an elite background — they both have PhDs, and they’ve both worked for top companies in the private sector. I’ve met Japanese bureaucrats — often considered the best in the world, certainly selected from among that country’s elite — and while they were certainly smart and dedicated and very hard-working, I have to say that they didn’t quite have either the passion or the technical expertise that Kim and Khan evince in this interview.

Part of that is because America is new to industrial policy, and there are a lot of people who are very inspired and very eager to make it work. But part of it is because instead of career bureaucrats, Kim and Khan came from the private sector. They intimately understand the nature of the industry they’re partnering with, both in terms of how those business models work, and many of the technical details as well. That’s in contrast to Japanese bureaucrats, who tend to enter the bureaucracy right out of college (traditionally majoring in law or humanities), and who only go to work in industry after the end of their government career.

In fact, if industrial policy does become institutionalized in America — if programs like the CHIPS Act end up being the precursor to something less temporary — we may have discovered the template for recruiting industrial policy bureaucrats. In the U.S.’ freewheeling capitalist system, lots of smart people make money at the start of their careers instead of at the end, as in Japan. Why not have them come work in government after making some money in the private sector? That could partially solve the perennial problem of uncompetitive government salaries, and reduce well-known incentives for corruption. And it could lead to greater trust and understanding between government and the private sector.

Anyway, state capacity is important. There’s really no substitute for it. And thanks to policies like the CHIPS Act, America has a real chance to build up the kind of state capacity we haven’t had in a very long time, in the service of important goals that won’t get done otherwise.

5. YIMBY education

America and many other developed countries have gotten very used to stasis over the last half century. When a bunch of people started saying that we need to build a ton of housing and energy and infrastructure, this was naturally met with resistance, because it was unfamiliar. But there are signs that the more people learn about the program to rebuild our civilization, the more they like what they hear.

For example, Robinson Meyer reports that permitting reform is very popular in America right now:

Most Americans support the idea of a bipartisan law that would make it easier to build new clean energy projects while benefiting some oil and gas development, according to a Heatmap News poll conducted earlier this month…Some 52% of Americans said they backed the general idea of the legislation, the poll found. About a quarter of Americans opposed it, and roughly another quarter said they weren’t sure.

And here’s a paper by Elmendorf et al., finding that simply explaining housing markets to people makes them much more YIMBY in their attitudes toward market-rate housing:

Recent research finds that most people want lower housing prices but, contrary to expert consensus, do not believe that more supply would lower prices. This study tests the effects of four informational interventions on Americans’ beliefs about housing markets and associated policy preferences and political actions (writing to state lawmakers). Several of the interventions significantly and positively affected economic understanding and support for land-use liberalization…The most impactful treatment—an educational video from an advocacy group—had effects 2-3 times larger than typical economics-information or political-messaging treatments. Learning about housing markets increased support for development among homeowners as much as renters, contrary to the “homevoter hypothesis.”

This makes me think that what the Abundance Agenda most lacks is a bullhorn. The basic message — that America needs to build a lot more housing, energy, and infrastructure than we’ve been building in recent decades — just needs to get out there more. Americans are wary of change, but they like the idea once it becomes familiar to them.

6. Remembering slacker culture

“It's like every choice or decision you make...the thing you choose not to do...fractions off and becomes its own reality, you know...and just goes on from there forever.” — Richard Linklater

A whole lot of people on the internet seem to have become obsessed with this video of a barefoot, dreadlocked hippie girl named Amy from the mid-1990s:

She’s living a very carefree life — following the band Phish around even though she can’t get into any of their shows, crashing with friends, making hemp jewelry, getting stoned, and generally having a relaxed time in life.

I’m not sure why this video blew up at this moment, but I can tell you that this was a glorious time in American history. I’m a little younger than that girl, but I caught the tail end of that era, and it was every bit as relaxed and carefree as it looked. The slacker culture that prevailed from the late 1980s through the early 2000s was a glorious thing. It wasn’t just in the U.S., either — Japan had its own version of slacker culture that was just as beautiful3, and I bet Europe had something vaguely similar as well.

The question then arises: Why did that laid-back, artistic, carefree culture arise where and when it did? There are basically three explanations: economic, technological, and geopolitical.

The economic explanation is that the 1990s were a time of full employment and rising wealth. Perhaps that made young people feel like their future was guaranteed, so that they could take a few years off to follow a band around the country, and that instead of sacrificing their economic future it would simply make them a more well-rounded person. The challenge to this story is that for the last ten years — with the brief interruption of Covid — the U.S. has also been in a period of full employment and rising wealth, and yet the country’s youth have been gripped by unhappiness and tension.

The technological explanation is that after the invention of the car, but before the invention of the smartphone, young people had maximal freedom. The car gave you mobility — you could hop in your friend’s ride and cruise across the country on a whim. The 90s (and before them, the 1960s) also had cheap gas, which made this easier. Meanwhile, the lack of smartphones gave you isolation and anonymity — you could be cut off from anyone who wanted to find you, as well as the prying eyes of people wanting to judge you. You could reinvent yourself on a whim, remove yourself to a whole new setting, and forget whatever troubles you had had.

The third explanation is geopolitical. In the mid-1980s the Soviet Union began to weaken and ultimately collapse, ending the Cold War and the threat of nuclear annihilation. That was certainly a weight off of people’s minds — a world without the possibility of great-power conflict and nuclear holocaust was a world of bright possibilities. Even the War on Terror didn’t completely negate that feeling that the world was fundamentally at peace. And the global rise of liberalism — which you can clearly see in data sets like Freedom House’s rankings — might have made regular people feel more free to express themselves.

In any case, whatever it was, slacker culture feels like a distant memory now, both in the U.S. and in Japan. Economic times are good, but there’s no longer the general feeling that dropping out of the rat race to smoke some weed and hang out with your friends for a year or two, or working part time while you make your own clothes, is an acceptable life choice. In our pocket there’s always a screen waiting to suck us back into a world of strangers ready to judge us and lecture us — or maybe give us the attention we crave. And on the horizon, looming over it all, waits another multi-decade struggle against authoritarian powers.

But perhaps waiting for us at the end of that tunnel is another beautiful slacker era, for our children or grandchildren to enjoy.

In fact, Southwood et al. make a number of questionable arguments when attacking wind power. They argue that wind’s balance-of-system costs make it more expensive than fossil fuels or nuclear, and that it’s only kept afloat by government subsidies. But if subsidies are helping wind push out fossil fuels, electricity should still be cheap for the user in the UK, and the damage to growth should come in the form of high taxes rather than high prices. That is not what we observe. Southwood et al. also hold up nuclear as the favorable alternative to wind. But their argument for why nuclear is incredibly expensive to construct in the UK — basically, NIMBYism — is also their argument for why wind is expensive and has to be subsidized. It makes no sense to count NIMBY costs as part of wind’s “true” costs but not count them as part of nuclear’s costs.

If you have a pass-through business and you’re angry that I’m proposing to raise your taxes, realize that I’m also proposing to raise my taxes. Noahpinion is an S-corporation. I’m happy to pay higher taxes to the federal government, since these mostly go to fund either A) the military, B) public goods like research and infrastructure, or C) health care, food, and income support for the old and the poor. It’s state and local taxes that I resent paying, since in California these often end up getting doled out to corrupt nonprofits, and since we ought to be taxing property at much higher rates instead of income.

For just a small taste of what it was like, I recommend looking at the magazine Fruits and watching the movie Kamikaze Girls (if you can find it).

Sorry- I don’t want to rely on bureaucrats to pick winners. Government isn’t short of academically smart people- the issue is corruption, not smarts, and the US doesn’t have a history or tradition of technocratic and impartial bureaucracy. We are not Scandinavia or Germany or Japan. Probably closer to Sicily. There have always been smart underlings- the issue is that special interests and donors control their bosses. Tax credits or broad subsidies will allow the market to pick the winners. By the way. If you wish to have a program with some continuity, it needs to be passed on a bipartisan basis.

As for the 1990s fiscal policy, a big impact came from the Reagan-O’Neill social security tax hike and build up of surpluses there, plus the cuts in military spending.

President Obama reinstated something close to the Clinton taxes (with higher capital gains and dividend taxes plus the Medicare tax on investment income) and the tax take as a percent of GDP wasn’t very impressive.

Agree the pass through system is a scam, but I don’t think taxing businesses is very efficient. As we have seen with big tech and pharma and other IP-driven businesses of the future, corporate taxes are easy to evade and create disincentives and arbitrage.

Let’s tax people (and the revenues businesses make selling to people). Eliminate the corporate tax in favor of a GST on revenues with deductions for domestic labor expenses (perhaps up to a salary cap per worker) and domestic inputs. Stimulates production for export and also ensures that Google, Apple, Pfizer, et al pay taxes on what they sell here (obviously, like all business taxes, it is the people really paying the tax rather than the business). Supermarkets have a lot of domestic expenses so the effective GST for them will be very low, while the tech companies have huge profit margins and foreign royalty expenses from American IP they shifted to Ireland, Lux, Switzerland, etc which would not be deductible.

Tax capital gains as ordinary income and eliminate most deductions (except for a standard deduction). Perhaps give everyone 20k per year (carried forward) they can use as an exclusion for capital gains and investment income, for mortgage borrowing, for charitable contributions, state taxes, whatever), Eliminate the estate tax and step up basis on death and apply a capital gains tax at death (as Canada does or did) maybe with a few million exclusion before taxes apply a deferral for family-run businesses, farms, etc. Eliminate the charitable deduction for appreciated assets donated to foundations, endowments and DAFs. An immediate deduction should only be available for funds meant to be distributed that year in actual charity. Tax the investment income in foundations and endowments that hasn’t been distributed (on a rolling 3-5 year average basis to allow for losses).

It is illuminating that with all of your proposed tax hikes, only about 1/4 of the current deficit is covered and these tax hikes fall on the middle class as well as the rich. Puts to rest the campaign BS that we can have all sorts of new spending programs paid for by the rich. The rich can’t even cover our current deficits let alone any new handout. How would the Dems do in elections if people were told they were facing massive tax hikes just to cover the status quo- no more freebies, in fact, no freebies? How would the Repubs do in elections if people were told there would be no more tax cuts- instead, tax hikes?

Having lived in Europe where voters know that social democracy is paid for via regressive taxation and high average taxes on the middle and professional classes, and these voters accept that fact from both the right and the left, I find it curious that Dems have trouble winning elections selling the lie that the rich will pay for everything. How many votes would be won telling people (as in Europe) that you will be paying for your own benefits via regressive taxation?

While people talk about “entitlements” and then turn to social security and Medicare, the reality is that the annual deficits in social security and Medicare are fairly small and manageable as a percentage of GDP- though they will be problematic 10-15 years out.

“Entitlements” also include things like Medicaid and Obamacare which have skyrocketed and most people don’t consider to be “entitlements” like something they’ve had to pay payroll taxes on for decades.

Moreover the scam under budget reconciliation has been to “cut” Medicare (or use the social security surplus, during the GW Bush years) and then spend those “savings” (say, prescription drug negotiations or lower hospital reimbursements) on some new handout in perpetuity. Only in government could use alleged/projected savings from an insolvent program justify a spending blowout. As if you know your mortgage payment is going to reset in a few years from $2k a month to an unaffordable $5k a month. But good news - the bank has agreed to cut that to a still unaffordable $4.5k…….so of course you immediately go out and increase your spending today by $500 a month.

Would love to change the reconciliation rules so that any payroll tax hikes or benefit/expense reductions in social security or Medicare could only be used to make those programs more solvent (the Al Gore “lockbox”).

Meanwhile, outside of those old age programs, there is zero reason at full employment why the rest of government spending shouldn’t be completely balanced. Would love to see proposals from both parties on how they would balance non-soc sec and Medicare spending. Would be amusing and eye opening. People have no idea how big a hole we have dug,

Not to worry, if Trump is elected and Republicans take tbe senate the media will decide that the deficit is suddenly an issue again.

The video of the hippie Phish chick is classic. No phone in hand, but rather a cigarette. Takes me back. Sadly, those carefree days are gone. The end of history didn't work out so well and we blew that peace dividend to smithereens. Hindsight is 20/20.