At least five interesting things for your weekend (#15)

Working-class wealth, the education gap, zero-sum thinking, data uncertainty, and indigenous knowledge

We begin, as always, with podcasts. One strange thing about me is that I think my voice sounds pretty awful inside my own head, but sounds pretty good when I hear it recorded. I’ve heard most people are the exact opposite. I wonder why!

Here’s my appearance on Jordan Schneider’s ChinaTalk, along with Matt C. Klein of The Overshoot:

Here it is on Apple Podcasts if you prefer. We talk about whether China has peaked, and go over the economic challenges facing the country. Matt and I are basically in agreement. China is at or near its relative peak, but it’s still capable of amazing feats, it dominates global manufacturing, and it’s unlikely to decline soon.

And here’s the latest episode of Econ 102 with Erik Torenberg:

Here’s Apple Podcasts and here’s YouTube. We talk about the coming age of globalization, which will see industrialization spread to South and Southeast Asia. We also touch on the coming age of fiscal austerity pressure in the U.S.

Anyway, on to this week’s Five Interesting Things.

1. Working-class wealth is improving

One of the truisms many Americans learned during the 2010s that turned out not to be so true is the idea that the wealth of the working class is relentlessly falling behind. The likely reason that people “learned” this “fact” is that it was true up until the financial crisis of 2008, and people didn’t recognize it and get mad about until the crash.

But anyway, if you’ve never seen the Fed’s Distributional Financial Accounts data, you really should take a look. It allows you to graph the components of wealth — real estate, stocks, consumer debt, and so on — by percentile, and with various demographic breakdowns. Frustratingly, there doesn’t seem to be an option on their graphing tool to adjust for inflation, which is important because inflation determines how much real stuff people can buy for a given dollar amount of wealth. For that we have to turn to the FRED website. But when we do, we can see that the bottom 50% of households have seen strong wealth growth in real terms since 2012:

And we can go back to the Fed’s DFA website to see the share of the country’s wealth that the bottom 50% holds. This too has been on the upswing after decades of declines:

Now, 50% of the country’s households holding only 2.5% of the wealth is still very dramatic inequality. We should remember that some piece of this is just the life-cycle of wealth — young people who haven’t had time to build wealth and old people who have spent down most of their retirement account will look poor even if they will be comfortable or were comfortable in middle age. But even after accounting for that life-cycle effect, America is going to have very steep wealth inequality.

Trends are important, though. And this trend is a positive one. The fact that working-class wealth has been recovering as a share of America’s total wealth for a decade, even as every group has increased its wealth, says that something is going right in the U.S. economy. A rising tide is lifting all boats, and it’s lifting the boats at the bottom more than the others.

The next question is why that’s happening. The DFA site gives some clues. If you toggle through the various wealth categories, you can see that the Bottom 50% has seen their wealth increase in most categories, but hasn’t seen their share of wealth really increase within any one particular category. This means the trend of falling wealth inequality is a composition effect — what happened is that American wealth overall shifted toward categories where the working class have higher shares. One obvious example of this is that household debt has become less important as a share of GDP since the financial crisis:

Working-class people tend to have a lot more debt relative to their assets, so household deleveraging as a whole tends to decrease wealth inequality. So if we want to keep the positive trend going, one idea is to help working-class people pay down their debts.

2. Educated people are much healthier in America

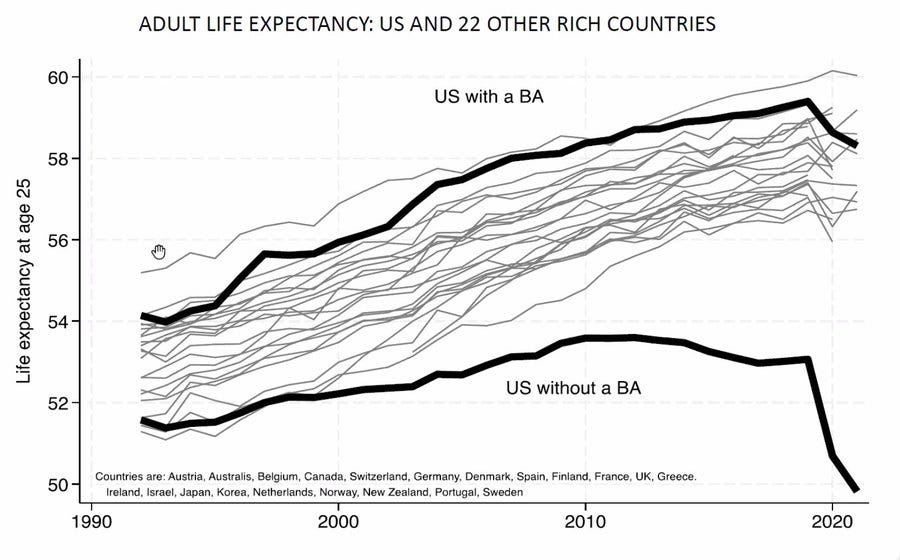

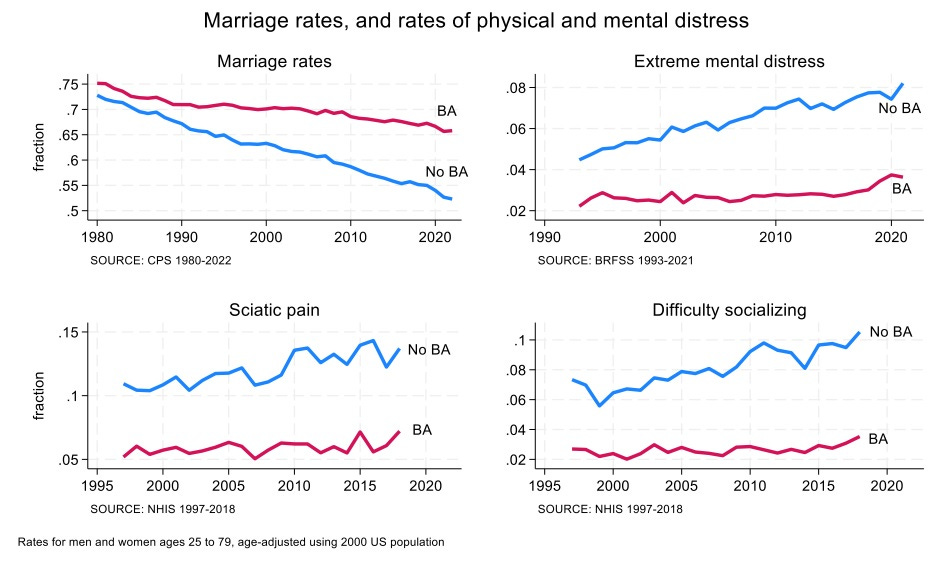

So, that was the good news regarding inequality in America. Here’s a piece of bad news: Americans are increasingly divided by health inequality according to education level. The graph at the top of this post, showing much bigger life expectancy declines for Americans without college degrees, is from a recent Brookings paper by economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton. They find that the education gap has increased across a startlingly wide variety of health and social outcomes — everything from mental distress to difficulty socializing:

Kevin Drum points out that this emerging gap is mostly among White Americans.

Now, when you see changes like this, you always want to think about composition effects. Over time, more and more Americans have gotten college degrees

This compositional change can affect both overall life expectancy for the college and non-college groups, and the gap between the two.

For example, suppose society is made up of three equally-sized groups of people: Alphas, Betas, and Gammas (thanks to Aldous Huxley for the names). The Alphas have life expectancy of 90 years, the Betas 80 years, and the Gammas only 60 years. Suppose that at first, only Alphas go to college, so the college life expectancy is 90 and the non-college life expectancy is 70 (i.e., the average of 80 and 60). Now suppose the Betas start going to college. The college life expectancy declines to 85 (the average of 90 and 80), and the non-college life expectancy declines from 70 to 60 (because only the Gammas are now without college degrees). In this example, life expectancy for society as a whole hasn’t changed, nor has life expectancy for any of the three groups changed, and college itself has absolutely no causal effect on life expectancy. All that changed was an expansion in the fraction of people who go to college.

In other words, if the people who are more likely to go to college also tend to live healthier lifestyles — maybe because they’re more conscientious, or because they’re richer, or because they have better family values, or whatever — then an expansion of college to more marginal people will reduce life expectancy for both the college and the non-college groups. And if the least healthy and least college-bound group is very unhealthy, this composition effect will increase the education gap as well.

Now, Case and Deaton are aware of this. They try to control for composition effects by looking within birth cohorts — for example, just looking at people born in 1990. Once those people pass the age of 25 or so, their likelihood of completing college shouldn’t change much (it changes a little, because of “continuing education” students, and because some older people start lying on surveys and saying they have degrees when they don’t). What they find is that the mortality gap between the college-educated and the non-college educated increases over time for more recent cohorts (Millennials and Zoomers), while staying flat over time or even decreasing for older cohorts (Boomers, etc.).

It’s hard to tell a simple story about exactly what that means, but what it does suggest is that in recent years, the fortunes of college-educated and non-college-educated young Americans have been diverging. College does appear to provide some causal protective effect against the general wave of unhealthy lifestyle changes — obesity, drug overdose, suicide, and murder — that have afflicted the country in recent years. That’s consistent with research that tries very carefully to account for selection effects.

The likeliest story here is that modern America has very few institutions capable of teaching young people to live healthy lifestyles, and that college is simply one of our few remaining institutions that does this. I’m open to alternative stories, of course.

3. Strong arguments about zero-sum thinking

Sahil Chinoy, Nathan Nunn, Sandra Sequeira and Stefanie Stantcheva have written a very interesting and potentially important paper about the rise of zero-sum thinking in the United States.

A lot of pro-growth people — myself included — believe that one reason economic growth is good is that it prompts people to think about growing the pie rather than fighting each other over how the pie is divided. We notice that before the Industrial Revolution made growth the norm, there was a lot more conquest and endemic war. This sort of made sense, because if you lived in the year 1200, the way to get rich was to take your neighbor’s land. In the year 1900, the way to get rich was to start a business. Obviously we still have some wars, and there are many non-economic reasons for conflict, but if a rising tide lifts all boats, it seems reasonable to think that people will be more content not to beggar their neighbors.

Anyway, in order to investigate this story, Chinoy et al. do a big survey of Americans, to try to figure out how zero-sum their attitude is. They ask people four questions, each of which can have five responses (from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”):

1. Ethnic: “In the United States, there are many different ethnic groups (Blacks, whites, Asians, Hispanics, etc). If one ethnic group becomes richer, this generally comes at the expense of other groups in the country.”

2. Citizenship: “In the United States, there are those with American citizenship and those without. If those without American citizenship do better economically, this will generally come at the expense of American citizens.”

3. Trade: “In international trade, if one country makes more money, then it is generally the case that the other country makes less money.”

4. Income: “In the United States, there are many different income classes. If one group becomes wealthier, it is usually the case that this comes at the expense of other groups.”

They combine the responses to these questions into an index of zero-sum thinking, and they find that the index is higher for Americans who were born more recently.

Note that this doesn’t necessarily mean zero-sum thinking is increasing over time! Since they’ve only done the survey once, all they know is that older Americans show less zero-sum thinking than younger ones. Sure, if people’s attitudes are fixed, then yes, this does show more zero-sum thinking over time. But we don’t know if attitudes are fixed! Maybe age and experience teach people to be less zero-sum in their thinking? We won’t know until this survey is repeated over decades.

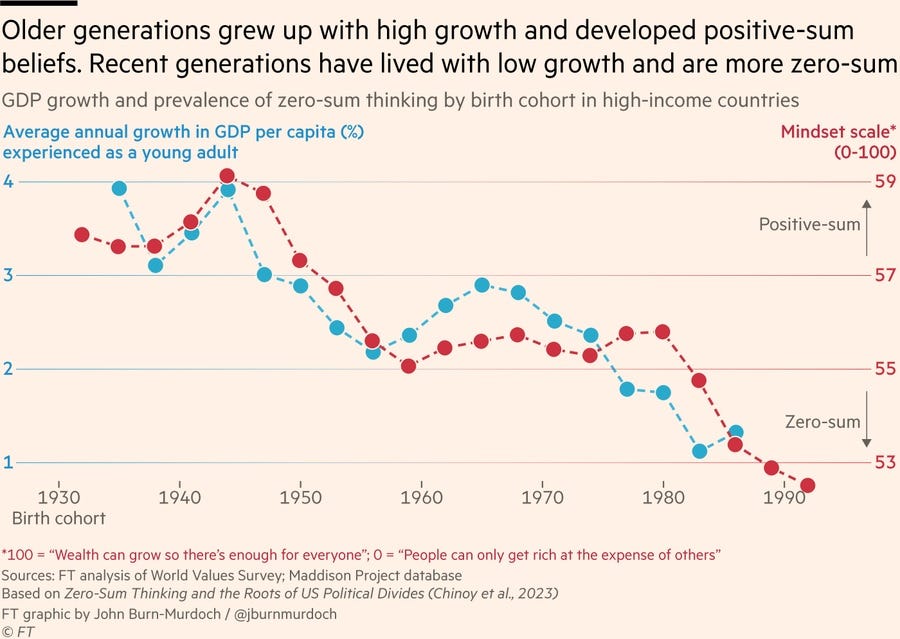

But anyway, a lot of people are interpreting the pattern as an increase in zero-sum thinking over time. And of course economic growth has fallen over time in the U.S., due to a variety of factors. So it’s tempting to assume that the one causes the other. John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times created a chart lining up the two and suggested that the standard story of growth as the antidote to zero-sum thinking explains the overlapping trends:

Now, this chart displays at least two of the red flags I’ve warned you all to look out for when assessing these viral charts. First of all, it’s a dual-axis chart. Dual-axis charts make it very easy to line up two lines that generally go in the same direction over time and make it look like they’re tightly correlated. To see how that works, let’s look at a very similar dual-axis graph from the paper itself:

Now, this still shows two lines, one of which goes up and the other of which goes down (since in their original index, a higher value means more zero-sum thinking; the reverse of what it means in the FT’s graph). It still shows a little bump in the 1980 birth cohort that might show a short-term causal effect. But this isn’t the kind of chart you’d look at and go “Wow, those two things have got to be the same thing!”. All we really know is that growth has fallen over time and zero-sum thinking — at least, measured by this survey index — has increased over time. Those could be due to completely unrelated trends.

Second, note that Burn-Murdoch’s y-axes don’t start at zero. That’s often fine, but in this case, it makes it look like a 6-point change in a 100-point index is really big. But is it really big? How significant is a 6-point change in the zero-sum thinking index? The authors correlate their index with other survey questions (e.g. support for redistribution and immigration), but those are also survey indices, and we don’t know how much they affect any kind of real economic behavior or voting behavior or anything.

So basically, we have no idea if this is a big important change or a tiny insignificant change.

Keep in mind that I do basically believe in the story the paper (and the FT) are telling here. But that’s just my own prior. Chinoy et al. have written a good and interesting paper, but it’s hard to say how much this one paper should strengthen my belief.

4. Getting good data is really hard

I toss out a lot of economic data on this blog, and it’s very natural to just accept this data as true and correct. But it’s important to remember that a lot of this data is really hard to gather, and there are usually a lot of assumptions that go into constructing it.

For example, check out this data of historical GDP per capita in the UK over the past thousand years, courtesy of the Maddison Project:

But the UK didn’t keep really good economic statistics until very recently. So how do we know these numbers for the 1700s, much less for the 1100s? The answer: assumptions about the technology available to the people at the time. These assumptions go into the numerator (total economic output) and the denominator (population), because we assume that a certain mix of agriculture, shipping, handicrafts, etc. would be able to produce a certain amount of goods and would be able to sustain a certain number of people. Change those technological assumptions, and the historical data can change a lot. I recommend the recent article by Timothy Guinnane about how sketchy our guesses about past population levels can be.

But even modern statistics have plenty of issues. Check out this thread by Neil Mehrotra about how he found a discrepancy in official energy prices. Basically, we know that natural gas, solar, and wind have all gotten cheaper in recent years, so it was weird that the official price index for electric power structures showed a steep increase. So Mehrotra got the Bureau of Economic Analysis to call up the Energy Information Administration and the Census and work out the discrepancies. The agencies eventually decided that electric power structures were a lot cheaper than the BEA thought, and made some revisions. This ended up increasing our estimates of real investment over the last decade.

So does this mean you should trust economic data more, or less? Well, the answer to that depends on how much you trusted it before. If you simply believed every number you ever saw, then it’s good to realize that these numbers contain a lot of “mystery meat” and are subject to a lot of revisions. But if you’re one of those people who just assumes official numbers are fake, then you should realize that smart and dedicated people are always challenging and revising these numbers. The bad news is that we don’t actually know how good our data is before we try to pick it apart, but the good news is that lots of people are trying very hard to pick it apart.

5. The difference between indigenous knowledge and science

Every so often you see some extremely progressive people claim that indigenous knowledge is a form of science — or is equivalent to science in its ability to teach us about the world. Perhaps the strongest advocate for this idea is Jessica Hernandez, an environmental scientist at the University of Washington. A lot of online people support her viewpoint:

But Hernandez is deeply wrong. Indigenous knowledge is not science.

That doesn’t mean that indigenous knowledge is worthless, or somehow “below” science on some hierarchy of ways of understanding the world. No such hierarchy exists, except in the minds of people who like to make hierarchies of things. But the two concepts are very distinct.

As philosophers of science like Thomas Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend have noted, there’s no single scientific method; scientists use various different methods in different disciplines and at different times, and usually manage to advance our understanding of the world in some way. But that doesn’t mean that anything anyone thinks they know should be labeled “science”; to do that would simply be to rob the word of all usefulness.

Instead, I think there are a couple features of science that are common across different paradigms and methods that clearly distinguish it from indigenous knowledge.

First of all, there’s transferability. People who use the phrase “Western science” are fundamentally misguided; science is not Western, but universal. The reason we know this is that all scientific knowledge and all scientific methods are fully transferable; it’s possible to teach anyone how to do science in such a way that they can do it better than the people who taught them, and better than Westerners. In fact, that’s not an aspirational or hypothetical statement; we’ve seen it happen in real time, within our lifetimes.

Contrast this with indigenous knowledge. Imagine a newspaper headline declaring that “China retains crown in indigenous Zapotec knowledge”. That sounds like something The Onion would write. It makes no sense to us, because we assume that indigenous knowledge is specifically bound to a group of indigenous people. Science is not.

Note that this doesn’t make indigenous knowledge useless; in fact, it can be an advantage in some situations. China may be #1 in science, but it’s having great difficulty reinventing Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography technology for high-end semiconductors. TSMC, Zeiss, Cymer, and a handful of other companies have distributed tacit process knowledge that may draw upon science, but are fundamentally things that can’t be reverse-engineered with science — and thus are very hard for China to steal or otherwise appropriate. I would argue that this distributed tacit process knowledge, arrived at by tinkering rather than experiment, is similar to indigenous knowledge — indigenous, perhaps, to a particular corporate culture. Its non-transferability makes it valuable.

The other aspect of science that is common throughout various paradigms and methods is that it’s testable; you can always appeal to the outside world to tell which ideas are right and which are wrong. The man who’s generally regarded as the first modern scientist, Ibn al-Haytham of Basra — arguably not a Westerner himself — summed this up in a famous quote:

Therefore, the seeker after the truth is not one who studies the writings of the ancients and, following his natural disposition, puts his trust in them, but rather the one who suspects his faith in them and questions what he gathers from them, the one who submits to argument and demonstration, and not to the sayings of a human being whose nature is fraught with all kinds of imperfection and deficiency. The duty of the man who investigates the writings of scientists, if learning the truth is his goal, is to make himself an enemy of all that he reads, and…attack it from every side. He should also suspect himself as he performs his critical examination of it, so that he may avoid falling into either prejudice or leniency.

When Richard Feynman expressed similar ideas in his famous 1966 speech “What is Science”, he was just paraphrasing al-Haytham.

Now in principle, indigenous knowledge is testable. But in our American understanding of the idea — the concept that Jessica Hernandez wants to promote — indigenous knowledge is not subject to testing by non-indigenous people. If as a non-Zapotec, you walk up and tell some Zapotec people that their ideas don’t fit reality and are wrong, your critique will not be accepted as indigenous knowledge by people like Hernandez. But if you walk up to some scientists and demonstrate with evidence that they’re wrong, your demonstration has a good chance of being labeled “science”.

In sum, indigenous knowledge is not science. Science can attempt to learn useful things from indigenous knowledge, but that doesn’t make the two concepts equivalent in any way.

Indigenous knowledge _becomes_ science when it is translated into rigorous models that make predictions about the world, and those predictions are tested against what actually happens in the world.

I may be mis-remembering, but I _think_ it was Scott Alexander who had an essay about how when folks like that Twitter shouter decry "Western culture" -- liberal syncretic cosmopolitanism -- the thing they're angry at isn't even actually Western, it has roots that go back at least to the early Ottoman empire's tolerance of other cultures in Istanbul, and to folks like Ibn al-Haytham. It's fundamentally characterized by not caring about the ancestry or pedigree of the ideas it embraces -- it just cares that things _work_. It's very hard to persuade your kids to continue Time Honored Traditions when they have the choice to go sample the best on offer from every culture in history, plus things that are being invented by the profusion of creativity of an interconnected world. Bulgogi tacos aren't Korean or Mexican or American or really anything else -- they're just _delicious_. And the Japanese and Taiwanese have been advancing Western culture at least as much as anyone in the actual West, in the last half-century or so. They've punched _way_ above their weight class, comparing the percentage of population to the value they've delivered in technological and cultural advancement.

For millennia we had various forms of ancestor-honoring, blood-and-soil tribal cultures, and then some mad Arab summoned Cosmopolitanism from the void, and exactly as you'd expect for a horror out of the Necronomicon, it proceeded to devour the world. I sorta get why so many people are freaked out by this, but I for one welcome the memetic Beast from Beyond -- it's made the world a lot _better_ than what came before.

"But Hernandez is deeply wrong. Indigenous knowledge is not science."

Sorry, Noah, but she said it 8 times, so she must be right. That's how proggie twitter works. Do better.