At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#17)

Techno-optimism, the mighty U.S. economy, Chinese real estate, slavery's economic effects, and the danger of hate on social media. Plus, rescue rabbits.

Apologies for being slow with blogging this week. I’ve been working on my epic review of Power and Progress, and it’s getting…long. I also wanted to take an extra day to let people read my post from Sunday. But anyway, there are a lot of things I wanted to blog about, so I’ll do another roundup.

No new podcasts yet this week, but I do have one unusual request. As regular readers of this blog know, one thing I care a lot about in life is taking care of rabbits. I like cats and dogs just as much, but rabbits don’t get nearly as much attention, and as a result they often get treated very badly. My own rabbits were rescued back in 2016 from some guy who was trying to breed rabbits illegally in his garage, in absolutely horrible conditions.

Anyway, there was another similar rescue in the Bay Area recently, in Petaluma — dozens of rabbits saved from very cruel living conditions. The rabbit rescue that originally rescued my own rabbits, SaveABunny, reached out and asked if I knew anyone who might be able to help. So if you’re in the Bay Area, and you also like rabbits, and you think you might want to help take care of one, please email them at rescue@saveabunny.org, or go to their website, or respond to their Facebook post.

Anyway, on to this week’s Five Interesting Things.

1. Techno-optimism resurgent

As you know, I’m a dogged techno-optimist. I think we consistently underrate the power of science and technology to change our world for the better, and we underinvest in both. (You can expect my review of Power and Progress, whose central thesis is that techno-optimist ideas have deeply damaged our economy, to be a feisty one.) But there are people out there whose techno-optimism is so intense that it puts my own in the shade. One of these is Marc Andreessen.

In a new essay/rant called “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto” over at a16z’s website, Marc lays out his vision. Here are a few points I’d like to highlight.

First, Marc focuses squarely on technology’s ability to bring abundance. And he appropriately frames abundance not just as “more stuff”, but as more choice in general for human beings, and more control over our world.

We are materially focused, for a reason – to open the aperture on how we may choose to live amid material abundance.

A common critique of technology is that it removes choice from our lives as machines make decisions for us. This is undoubtedly true, yet more than offset by the freedom to create our lives that flows from the material abundance created by our use of machines.

Material abundance from markets and technology opens the space for religion, for politics, and for choices of how to live, socially and individually.

We believe technology is liberatory. Liberatory of human potential. Liberatory of the human soul, the human spirit. Expanding what it can mean to be free, to be fulfilled, to be alive.

We believe technology opens the space of what it can mean to be human.

I couldn’t agree more, and I think this is extremely well-put.

This is also a very important paragraph:

We believe there is no conflict between capitalist profits and a social welfare system that protects the vulnerable. In fact, they are aligned – the production of markets creates the economic wealth that pays for everything else we want as a society.

Degrowthers — whom Marc correctly identifies as an enemy of human progress — believe that there’s an inherent tradeoff between human abundance and nature. This is a story of technology as fundamentally extractive, which fits neatly into a zero-sum worldview where prosperity is all about the extraction of resources rather than the creation of novelty. But Marc correctly realizes that technology is what allows humanity to reduce our natural footprint even as we create abundance for ourselves:

Natural resource utilization has sharp limits, both real and political…And so the only perpetual source of growth is technology…We believe technology is a lever on the world – the way to make more with less.

I also agree with Marc that culture matters. The last ten years have been a decade of unrest in American society, in which existing status hierarchies were unsettled and challenged across our entire culture. Because technologists and tech companies often make a lot of money and are thus high on the status totem pole, a fair amount of ire was directed their way. (The highest intellectual expression of that ire is the book Power and Progress, which I’m currently in the middle of reviewing.) Marc’s essay lashes out at these critics:

Our present society has been subjected to a mass demoralization campaign for six decades – against technology and against life – under varying names like “existential risk”, “sustainability”, “ESG”, “Sustainable Development Goals”, “social responsibility”, “stakeholder capitalism”, “Precautionary Principle”, “trust and safety”, “tech ethics”, “risk management”, “de-growth”, “the limits of growth”.

Here I take a more balanced view, but still ultimately come down on Marc’s side. Some of the ideas and institutions he lists as the “enemy” are useless, but many of them have some value. Sustainability, for example, is actually a goal of technological progress — as Marc himself acknowledges earlier. Existential risk is an important thing to worry about, which is why nerds celebrate the day that Stanislav Petrov’s judgement saved us from a nuclear war.

But Marc is right that most of the forces and institutions that have set themselves up as enemies of techno-capital were given extra force and virulence by the general climate of unrest in America (the unsettling of status hierarchies being what Marc, referencing Nietzsche, refers to as “ressentiment”). So Marc is right that it’s time for a useful corrective — a general social refocusing on technological progress, abundance, and optimism.

There is one area where I might disagree with Marc, though. While he’s right that markets are a crucial engine of innovation, I do think he underestimates the role of government in pressing science and technology forward:

We believe central planning is a doom loop; markets are an upward spiral.

The economist William Nordhaus has shown that creators of technology are only able to capture about 2% of the economic value created by that technology. The other 98% flows through to society in the form of what economists call social surplus. Technological innovation in a market system is inherently philanthropic, by a 50:1 ratio. Who gets more value from a new technology, the single company that makes it, or the millions or billions of people who use it to improve their lives? QED.

But in fact, the second paragraph explains exactly why the first sentence in this quote isn’t quite right. It’s precisely because innovators don’t capture most of the monetary benefits of the innovations they create that we need some other force to propel technology forward. Yes, invention is philanthropy, and philanthropy isn’t enough!

That’s where government comes in. There are plenty of ways that government can and does encourage accelerated innovation — through R&D tax credits, through the patent system (sometimes), though funding of basic research at universities and national labs, through DARPA, and so on. Much of our technological innovation has been driven by this support, which works in harmony with markets instead of replacing them. In fact, Marc himself created the first widely usable graphical web browser while working at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, a state-funded research center! And Marc correctly lists Paul Romer as a patron saint of techno-optimism; Romer has fought tirelessly for more government funding for science and technology.

If you don’t want to call that “central planning”, fine. But don’t forget the important role of government in pushing progress forward!

Here’s a good thread by Nick Pinkston making the same point.

Anyway, Marc is just one of a whole new crop of techno-optimists that has popped up in recent years. The e/acc movement — basically an online reboot of the extropian movement from the 1990s — is extremely fun. My favorite e/acc account is @terrorproforma.

Meanwhile, Packy McCormick, who writes the excellent Substack Not Boring, has a new series called “Age of Miracles” where he explores new technologies:

And of course there’s no shortage of actual technological miracles happening all around us. Malaria vaccines — created using the same technology that we deployed to fight Covid — are now being deployed, threatening to free humanity (and especially Africa) from one of our most terrible and deadly endemic diseases.

And that turbulence you hate whenever you fly on a plane? Well, that might soon be mostly a thing of the past, thanks to AI:

(Update: This may actually be done without AI! If so, that’s pretty amazing in and of itself.)

In fact, the combination of AI and physical technology promises to create a whole new era of innovation in “atoms”.

It’s a pretty great time to be alive. Time to shake off the malaise of the 2010s and dream big again.

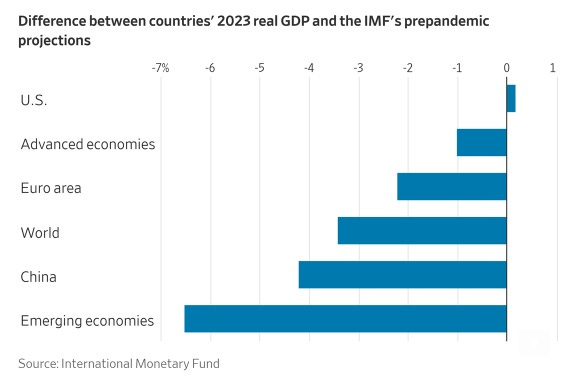

2. The U.S. economy remains undefeated

Usually you wouldn’t think of a U.S. economic boom as the type of story to fly under the radar…right? And yet the U.S.’ economic outperformance during the post-pandemic years, and especially over the last year, feels very underappreciated. Let’s look at a few charts.

First, there’s growth. Even as China and Europe have decelerated since the pandemic, the U.S. has grown faster than pre-pandemic forecasts expected:

And growth actually seems to be accelerating:

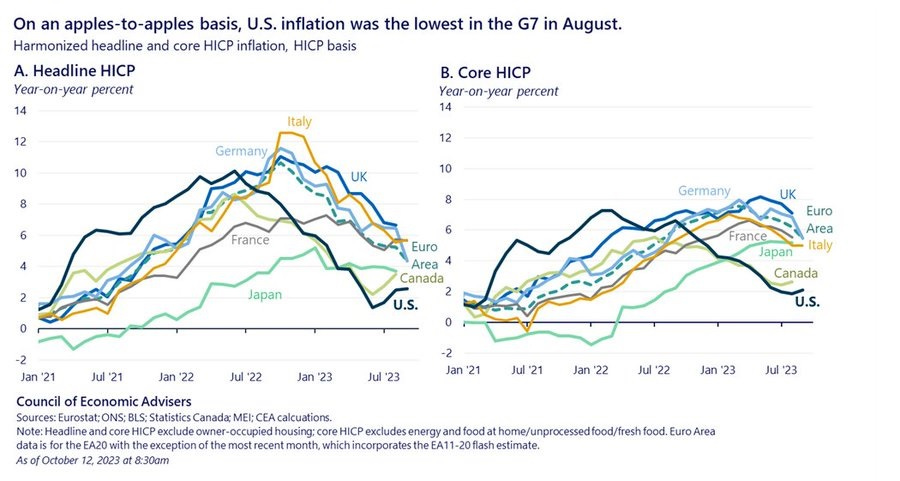

Usually you’d think this rapid growth would be a sign of “overheating” — that it would come at the expense of higher inflation. But while inflation is still a little elevated at around 3%, it’s much lower than in other rich countries:

And thanks to the drop in inflation, real wages are recovering from their post-pandemic plunge. For the typical worker, hourly earnings are now pretty much back at the pre-pandemic trend:

As for why this is happening, and what could threaten it, that’s a topic for a longer post. But right now we just need to realize that despite a two-year burst of inflation, the U.S. economy has been doing really, really well since the pandemic.

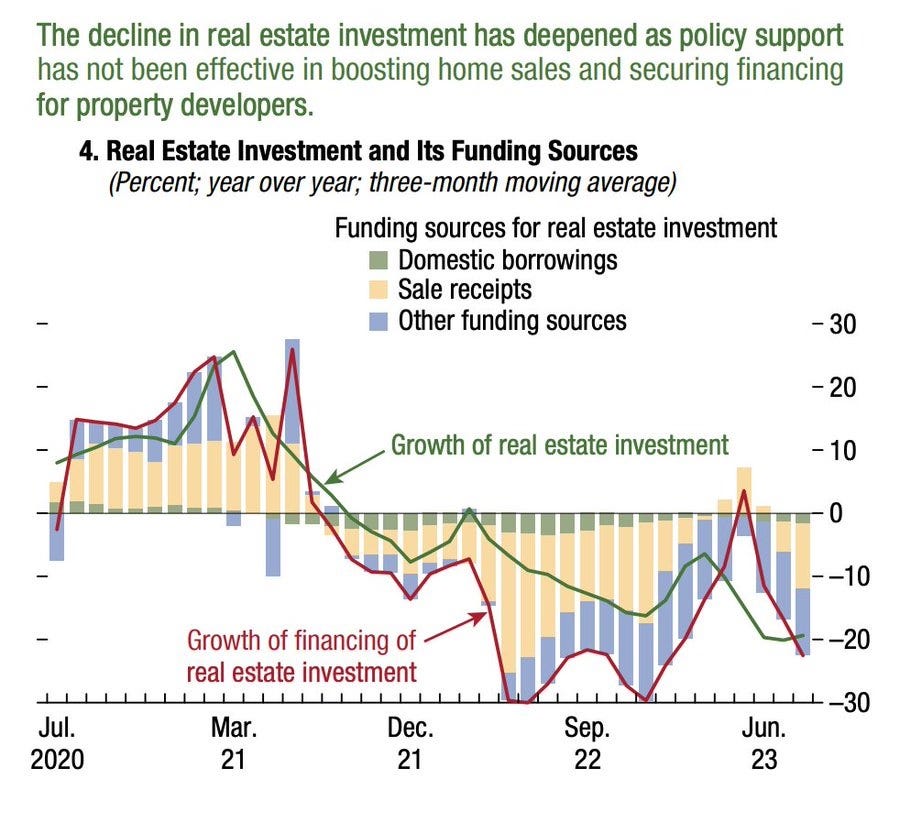

3. China’s real estate woes continue

A major economy that has not been doing really, really well since the pandemic is China. The basic pattern we all described two months ago — the inevitable crash of a bloated real estate sector, exacerbated by a dysfunctional local government financing system — is still in place. But it’s useful to check back and see that things are still largely playing out as forecasted. Adam Tooze posted a great chart with a zoomed-out view:

And the New York Times has a good summary and update.

A week ago, Chinese property developer Country Garden indicated that it’s going to default. This follows the pattern of Evergrande, which was the first domino to fall and is now facing liquidation. The Wall Street Journal points out that lots of investors thought the crisis was over and that they could scoop up Chinese real estate bonds on the cheap, only to get burned when it turned out that the bonds were worth even less than the pessimists thought. Meanwhile, it looks like a number of dominoes are still left to fall; Bloomberg’s Shuli Ren writes about private equity companies that are set to take big losses from the real estate implosion.

But the biggest loser is likely to be local governments. These governments financed much of their expenditure with land sales for years, and now with the property sector crashing, that revenue has dried up. So they’re largely surviving by borrowing. The problem is that no one wants to lend to the local governments, since they realize that the long real estate boom is probably never coming back, and thus the local governments are not going to have the money to pay back their loans.

So the central government is stepping in, telling state-controlled banks to keep lending money to the local governments at cheap interest rates. This is called “evergreening”, and it’s what Japanese banks did with failed companies after the bust of 1989-91. It basically amounts to a bailout by the central government, but with one added negative characteristic. If their lending is directed toward local governments (which are basically non-productive borrowers), state-controlled banks won’t be able to lend as much to the private sector, which could lower productivity and prolong the downturn — just like zombie lending did in Japan.

That said, China’s government will certainly try very hard to push banks to lend to non-real-estate-related sectors. Here’s an interesting chart posted by Bert Hofman showing a big burst of lending to industry:

China is going to try to replace the shattered real estate sector — which peaked at almost 30% of GDP — with a bunch of manufacturing. Time will tell how much of that manufacturing is actually anything people want to buy, or whether it’s setting China up for a glut of overcapacity and waste.

4. Slavery wasn’t just evil, it was bad for the economy

In the 2010s, it became fashionable to claim that the Industrial Revolution was enabled, or even caused, by American slavery. This idea served a number of rhetorical purposes, such as some socialists’ desire to equate capitalism with slavery, or some progressives’ urge to characterize everything about the American way of life as “stamped from the beginning” with the stain of slavery. This theory, which was part of the so-called “New History of Capitalism” and was largely promoted by historians rather than economists,

There was never a ton of evidence to back up this theory, but “not a ton” is not the same as “nothing”. One paper by actual economists estimated that the cheaper inputs from slavery did increase Britain’s national income by 3.5% — not quite “started the industrial revolution” levels, but not nothing either.

But there’s also a lot of evidence that slavery hurt the economy of the American South. A new paper by Richard Hornbeck and Trevon Logan describes why this was the case, and tries to quantify how much emancipation helped boost the economy. Here are some useful excerpts:

Characterizations of slavery as efficient and productive reflect the benefits and costs for slave owners, with market transactions oriented around extracting value from enslaved people. In this paper, we challenge this view. We re-characterize slavery as economically inefficient because there was a massive externality whose implications have been underexplored: enslavers considered their own private marginal benefits and private marginal costs of slave labor when making production decisions in the antebellum era, but they did not internalize the costs slavery imposed on enslaved people. When including costs incurred by enslaved people themselves, the tremendous inefficiency of slavery becomes readily apparent because the value extracted by enslavers was substantially less than the costs imposed on enslaved people. Focusing on the cost of enslavement to the enslaved shows that slavery was a market failure in addition to a moral failure.

Since American slavery was economically inefficient, in this aggregate sense, emancipation generated substantial aggregate economic gains. While output declined after emancipation, input costs declined substantially more, which increased aggregate economic surplus: the total value of output minus total costs incurred…Emancipation reduced input costs that were not paid under slavery, due to coercion, but were still incurred by enslaved people and reduced aggregate surplus in the US economy…[W]e calculate that emancipation generated economic gains that exceed estimated costs of the Civil War…Emancipation generated aggregate economic gains worth 7 – 60 years of technological innovation in the 19th century[.]

The argument here is actually a subtle but powerful one. Because slavers basically got to ignore many of the costs they foisted on slaves, they made poor decisions about how to spend slaves’ time and effort and skills — and the slaves were also forced to make bad decisions. As the authors write, “slavery was not only a substantial transfer of value from enslaved people to enslavers, it was also an inefficient mechanism of transferring value.”

(And as an aside, there are other, more complex distortions that this paper doesn’t even take into account, like investment decisions. Because slavers faced the wrong prices for their investment decisions — slave labor was artificially cheap — the slave states over-invested in agriculture instead of manufacturing. Which is why when William T. Sherman showed up to kick their butts, he lambasted them by saying “hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make”. This was one reason the Union won so decisively.)

Hornbeck and Logan’s result stands in contrast to the paper that found that slavery made Britain a little bit richer. Future research should focus on harmonizing the methodologies in these models — combining natural experiments from emancipation with the theory of externalities. But in any case, this is a blow to the idea that slavery was a boon for the overall economy.

Which doesn’t mean, of course, that the modern American economy is free from the stain of slavery. It just means that that stain is probably making us poorer rather than richer. Extractive labor policies like low-paid prison labor, commonly used in the American South, under-invest in human capital and are probably thus inefficient, for many of the same reasons that Hornbeck and Logan cite. In addition to being a human rights violation, of course.

5. The platform is the enemy

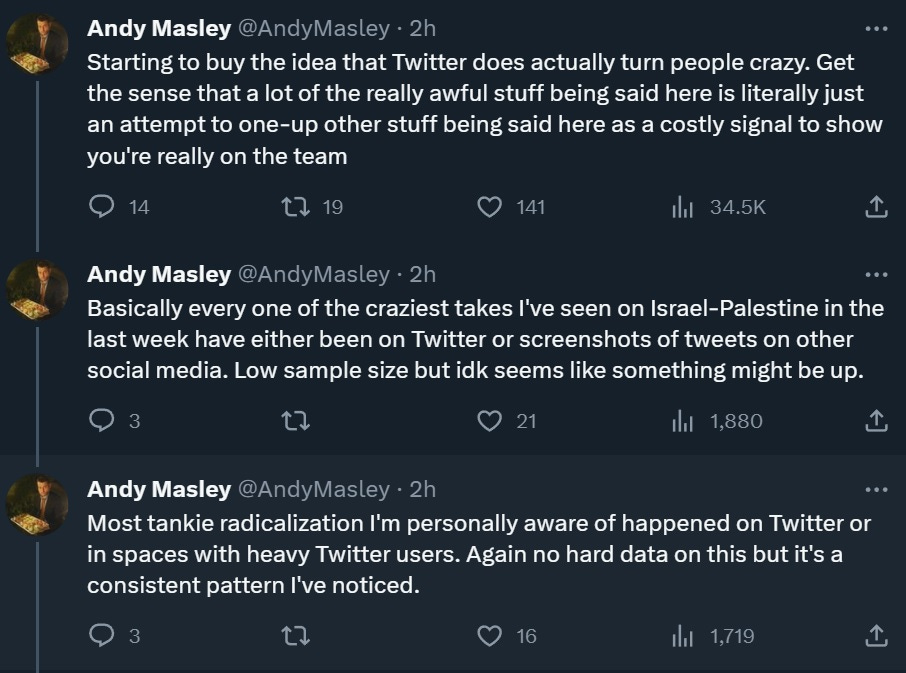

This past week on the platform formerly known as Twitter has been a tough one. The Israel-Gaza war has propelled the discussion to a level of insanity beyond anything I’ve ever witnessed. Other long-time users are noticing the same:

Of course some of this is because of the inherent divisiveness of the Israel-Palestine issue itself. But many of us have been warning for years that social media, and Twitter in particular, inherently rewarded divisive, extremist discourse, and elevated the worst people. There was no shortage of social science research supporting this finding, but more evidence continues to pile up all the time.

For example, here’s a new paper by Milli et al. about Twitter’s recommendation algorithm, which finds that the algorithm shoves divisive content in users’ faces that they would actually rather not see:

In a pre-registered randomized experiment, we found that, relative to a reverse-chronological baseline, Twitter's engagement-based ranking algorithm may amplify emotionally charged, out-group hostile content and contribute to affective polarization. Furthermore, we critically examine the claim that the algorithm shows users what they want to see, discovering that users do *not* prefer the political tweets selected by the algorithm.

But you don’t need a fancy recommendation algorithm to elevate the worst people; a new paper by Mamakos and Finkel finds that Reddit does this as well:

Toxic people are especially likely to opt into discourse in partisan contexts…[W]e analyzed hundreds of millions of comments from over 6.3 million users and found robust evidence that: (1) the discourse of people whose behavior is especially toxic in partisan contexts is also especially toxic in non-partisan contexts (i.e., people are not politics-only toxicity specialists); and (2) when considering only non-partisan contexts, the discourse of people who also comment in partisan contexts is more toxic than the discourse of people who do not. These effects were not driven by socialization processes whereby people overgeneralized toxic behavioral norms they had learned in partisan contexts.

This is not a causal study, and the effect is not incredibly strong, but it still shows that the tendency is there.

This doesn’t mean I think these new social media technologies were a bad invention (though Twitter’s algorithm certainly needs to be tweaked). It’s hard to imagine a world without even as simple and rudimentary an online discussion platform as Reddit! But what it does mean is that our society needs to adapt to the presence of these technologies. We need to start realizing that we have another enemy besides our traditional political opponents, and that enemy is the social media platform where we we get our news. Social media has taught itself to exploit natural human tendencies toward enmity and division, monetizing hate for engagement and profit. It’s a dark mirror to the worst parts of our souls, and it’s up to us to find ways to resist.

Per your point about radicalization happening on Twitter... one of the few/only critiques I have of your writing on substack is that your perception of different ideological groups seems to be overly-shaped by your experience on Twitter. Especially your critiques of the left seem geared towards left-twitter rather than an accurate assessment of how widespread various beliefs or ideological affiliations are actually distributed across various left factions.

“America’s economy is undefeated”. I would be up for a blog post on whether large US budget deficits could be corrected and whether this could be done without transferring the imbalances to other sectors of the economy.