At least five interesting things to start your week (#18)

Recession illusions, China's military buildup, industrial policy and wages, rethinking corporate tax, tightening export controls, and an interview with Darrell Owens

It’s been a while since I did a roundup, so I have not one, but TWO episodes of Econ 102 with Erik Torenberg this week. Here’s a fairly dark and dire episode about the danger of World War 3 and the end of Pax Americana:

Here are Apple Podcasts and YouTube links in case you don’t happen use Spotify.

And here’s a fairly cheery and upbeat episode about techno-optimism:

Here are Apple Podcasts and YouTube links for that one.

And here’s a little debate I did with techno-skepticChad Haag about techno-optimism on Lev Polyakov’s stream:

Anyway, on to this week’s Five Interesting Things!

1. No we are not in a recession, we are in the opposite of a recession

Social media was always full of totally wacky takes about the economy. But I feel like the takes are just getting wackier and wackier. Here’s someone claiming that we’re currently in a Great Depression!

That is, of course, completely, wildly, utterly untrue. It is the opposite of true. It is 180 degrees from the truth. It is, to put it bluntly, false.

The U.S. economy is doing GREAT right now. Real U.S. GDP growth came in at a 4.9% annual rate in the third quarter, which is as fast as China’s official growth rate, and is unusually fast for the U.S. The unemployment rate continues to hover near record lows at 3.8%, while the prime-age employment rate is near record highs at almost 81%. Inflation has come way down and is now around 3.7%, with core inflation a bit lower, and median wage growth is outpacing inflation. Meanwhile, new survey data shows that Americans have gotten wealthier, and wealth inequality has narrowed.

There is no sense in which this economy is doing badly. It is certainly very far from recession. And it’s about as different from the Great Depression as one could imagine.

And yet the “recession” narrative isn’t confined to random young people on TikTok and Twitter. Here is the eminent venture capitalist Jason Calacanis asserting that we are in a recession:

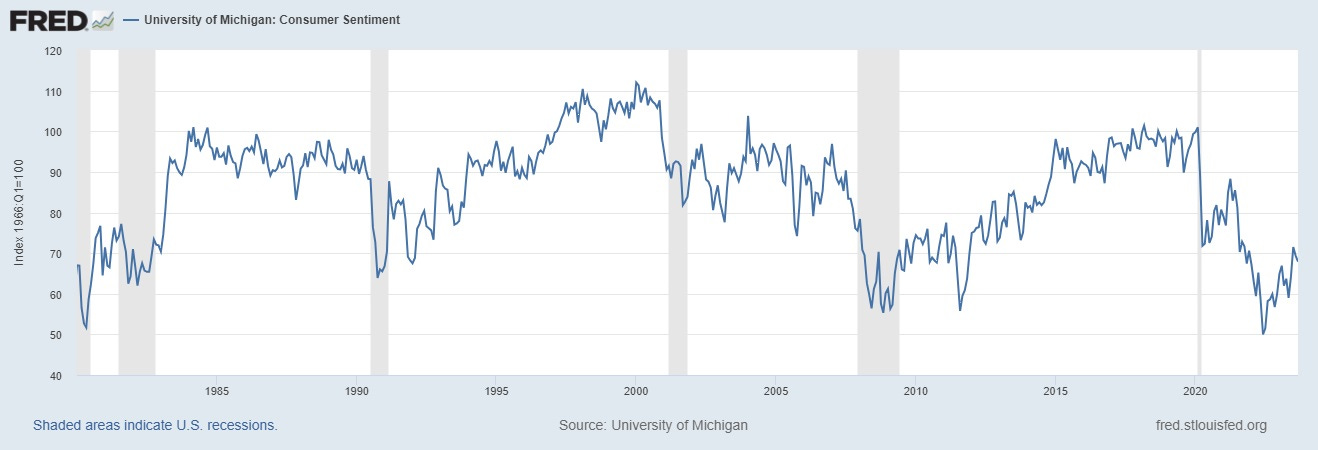

Now, perhaps Jason is just over-extrapolating from his own corner of the economy — tech startups are suffering as the cash they raised before the crash of 2022 runs out and can’t be replaced. But in fact, lots of Americans are saying very negative things about the economy these days. Consumer sentiment is still in the dumps despite all the economic good news.

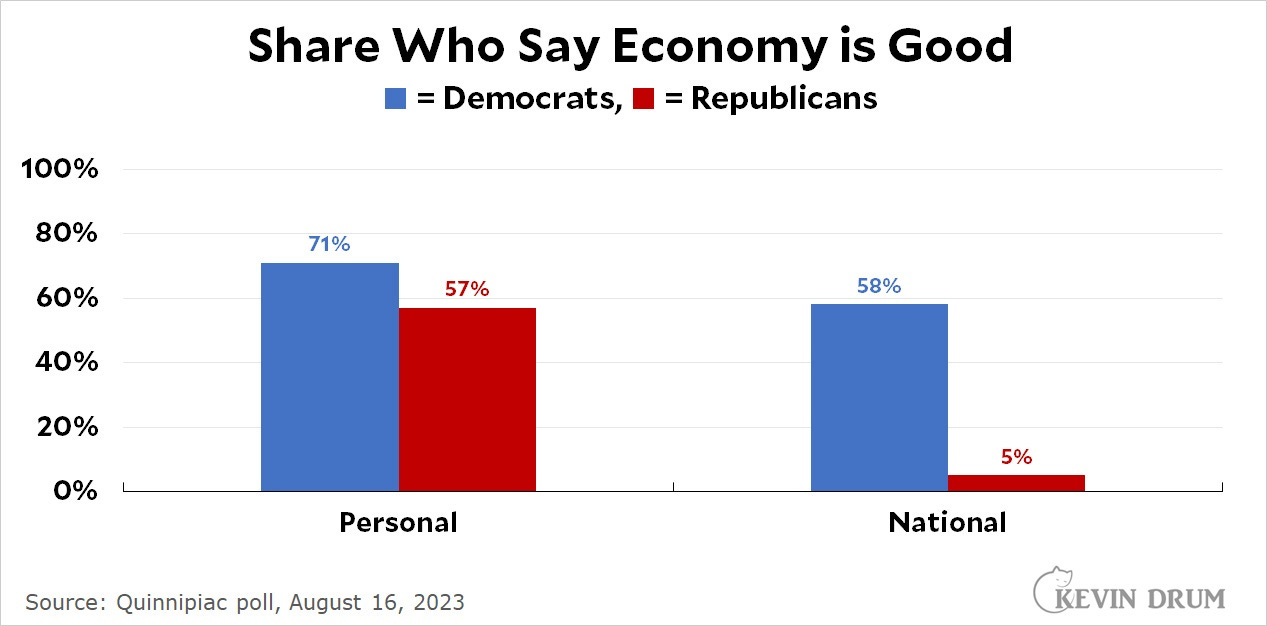

There are endless attempts at explaining this negativity, but I think a big part of it is just partisan emotional expression — or, as the kids call it, “vibes”. There’s plenty of data showing that Americans tend to rate the national economy as being much worse than their own personal financial circumstances. Well, Kevin Drum has some evidence that this national-personal split is mostly being drive by Republicans:

So it seems like GOP unhappiness with the state of the nation is really what’s driving the bulk of the negative sentiment here. If I were forced to guess, I’d say the memory of the summer of 2020 probably hangs over Republicans’ vision of the national situation, making them feel as if the country is turning against them in a way they never felt before.

2. China is building military stuff. America is not.

A new report from the U.S. Department of Defense shows just how rapid China’s military buildup is.

(First of all, don’t tell me that America spends much more than China on defense, because that just isn’t true; China keeps most of its military spending off the books, and because they get much more bang for their buck. In fact, military spending is probably roughly equal between the two countries.)

Here’s a great breakdown of the DoD’s report by defense analyst Tom Shugart (and here’s part 2). Basically, China is building huge numbers of ships, planes, and missiles. These are the weapons it will use to fight the U.S. in a war over Taiwan or the South China Sea. It’s also building a lot more nukes.

Some excerpts from Shugart’s threads:

[T[he PRC, through the increasing military capability of the PLA, is taking more coercive action against its neighbors in the region (just ask the Philippines & Taiwan). While improving its ability to fight the U.S., it seems largely uninterested in talking anymore…

The report puts the PLAN’s hull count at 370 this year, up from 340, and 140 surface combatants, up from 125…That 30-hull jump is more than I expected, as well as the 15-hull jump in surface combatants. I knew they were building, but not that they were building THAT fast…

In terms of future PLAN growth, DoD estimates 395 ships by 2025 and 435 by 2030…DoD estimates that the PLAN has now built 21 Yuan Class submarines in the last year, up from 17 in 2022…

Moving on to the PLA Air Force: this year’s report indicates that the PLAAF now has 1300 4th-gen fighters out of 1900 total (I assume that 1300 includes 5th-gen too), up *500* from the previous year…

The report shows major increases in every category of China’s long range missiles. Fielded ICBM launchers jump from 300 to 500, and the number of missiles goes up from 300 to 350…While the number of launchers stays the same, the estimate of the number of intermediate-range missiles (i.e., the “Guam Killers”) goes from a somewhat vague “250+” to a solid 500…

DoD now estimates China has a stockpile of 500 nuclear warheads, up 100 from last year. It also moves up its longer timeline to “over 1,000 warheads” by 2030, vice “about 1,500” warheads by 2036.

This is an absolutely astonishing rate of military buildup, and it’s not even wartime. It’s far, far beyond anything the U.S. can manage. China builds 21 submarines a year, while the U.S. struggles to build two. This is from last year:

The outgoing Trump administration then proposed a goal of 72 to 78 attack subs, and the Biden administration has since settled on a range of 66 to 72 — still far out of reach for the Navy unless something changes…

The industrial base, led by prime contractor General Dynamics Electric Boat and supporting shipbuilder Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Newport News Shipbuilding, has struggled to deliver two Virginia-class attack subs a year on schedule. The two yards each build different portions of the boats and then alternate who performs final assembly and delivery. For boat after boat, the contractors have delivered them to the Navy late.

The U.S. defense-industrial base has shriveled to a tiny fraction of what it was in the 1990s. Military analyst Patrick Fox has this to say:

One of the most conspicuous failures of the Biden administration has been their refusal to aggressively reindustrialize to increase our arms manufacturing capacity. The necessity became clear in 2022, it has only grown more critical in the interim.

He also shows yet more data on how much we’ve struggled just to build artillery shells for Ukraine — a tiny fraction of what we’d need to build for a conflict with China.

If you’re not worried about this, you should be. You can comfort yourself with the fact that U.S. technology is still a bit better than China’s (maybe), but the World Wars taught us that a huge advantage in quantity is decisive if your technology is decently good. The U.S. is now on the losing end of that asymmetry. There is no longer an arsenal of democracy in this world, and this fact should bother you.

3. Industrial policy isn’t really about low wages

There have been a lot of sloppy critiques of industrial policy over the last few months, and I’ll go over some more of those in another post soon. But there are some interesting and smart critiques out there too, which I feel like I should also address. For example, Matt Yglesias argues that industrial policy will struggle to create good jobs, because it relies on cheap wages as a source of international competitiveness:

Let’s say you’re a poor country…Then someone, tempted by the low wages in your country, builds a couple of factories….And now as an ongoing matter, his profit margins are really high because the wages are so low. The workers at the factory don’t like that and start talking about…going on strike, and demanding higher pay. What does the government do?…[I]f the government cares about industrial policy and creating a developmental state, it probably opts for labor repression and helps break the strike.

Why? Well, because even though the factory workers are underpaid…the whole strategy of national economic development is built on exploiting that fact…What you want to do is attract more investment, build more factories, and shift more workers off farms and into industrial work. That sectoral reallocation…is a strategy for raising wages…

[T]he go-to move of a developmental state is to be more hostile to worker interests than a free market would be…The dilemma for an already rich country like the United States is that it’s hard to see how a rich country can get richer by keeping wages low…[D]o you want to do your own industrial policy — wage suppression — to prevent the foreign competition from poaching your industry?

This critique is worth taking seriously, because it’s certainly possible to imagine that excessively high wages will make U.S. industry uncompetitive in international markets. Because their economy is big and relatively closed-off, Americans are used to thinking only in terms of producing for the domestic market. And you can protect the domestic market with tariffs and such.

But in fact, producing for the world market is extremely important, both because the world market is very big, and because producing stuff for the world pushes companies to raise their productivity levels. So here you have to be competitive, and not get undersold too badly by the Chinese competition. If American workers just strike and strike and get higher and higher wages unto infinity, eventually no one in India or Brazil or Germany will want to buy Boeing planes or Ford cars or Intel semiconductors; they’ll buy from China instead.

But quantitatively, how important are low labor costs? As evidence, Matt cites some historical studies suggesting that the Japanese textile industry outcompeted the Indian textile industry in the early 20th century by keeping labor costs low. But is there any reason to think that example is relevant for the U.S.’ situation in the modern day?

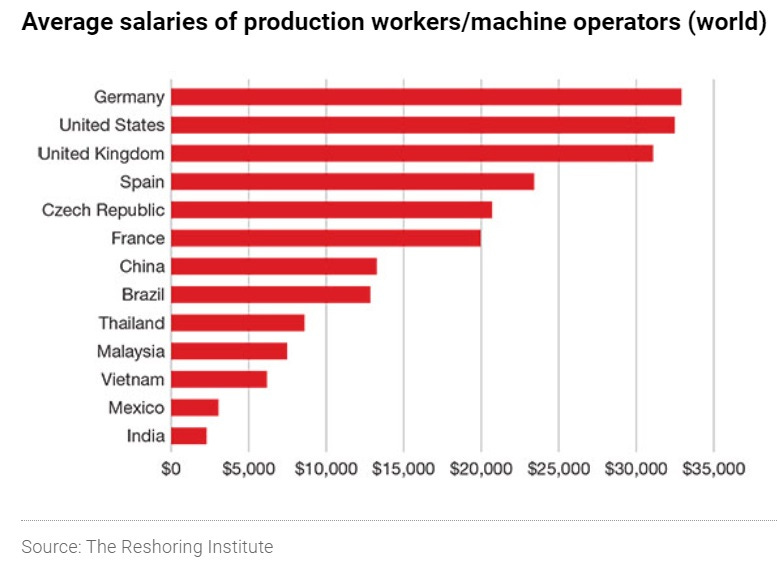

First of all, textile manufacturing at that time was extremely labor-intensive, meaning that labor costs loomed especially large (pun intended) in companies’ cost calculations. The high-tech manufacturing industries of the 2020s, such as the semiconductor industry, are very capital-intensive — you build a lot of machine tools, and then you staff the factories with PhD-level employees who know how to operate those tools. Yes, you need a few lower-skilled workers to set up and clean and guard the fabs and to bring the PhD people lunch and such. But these people’s wages are not going to be a big part of the production cost. The major labor costs you do have will mostly be the high salaries that you have to pay super-high-skilled workers; and as any tech company knows, these are not the type of workers who tend to form unions and push for ever-increasing wages.

In particular, we should look at what China has done right. China is not the center of global high-tech manufacturing because of low labor costs; indeed, its labor is no longer very cheap, and it hasn’t been considered a particularly low-cost producer for years now. Instead, China competes based on scale — it’s the only place you can build very large batches of high-tech products very quickly, thanks to its dense networks of suppliers and its huge labor force of well-trained production engineers. Meanwhile, Germany has even higher manufacturing wages than the U.S., and it’s well-known as a high-tech manufacturing and export powerhouse.

So Matt is formally right that excessively high wages could derail industrial policy, but it’s not clear how much that matters in real life. And Matt certainly isn’t right to equate industrial policy with wage suppression.

I do agree with Matt when he points out the importance of lowering non-wage costs like land and regulatory costs. But I think what his critique is missing is a consideration of productivity. What’s important for competitiveness isn’t labor cost or land cost or anything else, it’s “unit labor cost” — how much each unit of output costs to produce. The more productive a company is, the lower its unit labor costs, even if its wages are really high.

Of course, making land and regulatory approval cheaper are important ways to lower unit labor costs. But improving technology and encouraging automation is key as well. The real tradeoff we should be considering when it comes to industrial policy isn’t “wages vs. competitiveness” — it’s “factory job creation vs. competitiveness”. Industrial policy advocates don’t need to accept low wages; they need to accept that manufacturing industries create good jobs indirectly, through multiplier effects that boost local services.

4. Good news on solar power

Solar power is your friend. It is not a wimpier, less manly form of energy than coal or nuclear. It is not a tree-hugging hippie plot to destroy capitalism. It is not a desperate fallback that will have us living out of pods and eating bugs. It is a genuine technological revolution, a modern marvel by which the ingenuity of humankind has harnessed fusion energy from space and turned it directly into pure electric power.

More importantly, it’s just really really cheap. Jenny Chase, an analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, has a great annual thread where she assesses the situation of the solar industry. Here are a few choice tidbits from this year’s thread.

A lot of people used to claim that we need a technological breakthrough in solar cell efficiency in order to make solar economically viable. This was never true — it turned out we only needed cost reductions — but in any case, we did keep increasing cell efficiency incrementally, and those increases added up. Chase writes:

Incremental improvements in solar modules continue. 2023 was the move from PERC (module efficiency ~21.3%) being the standard design, to TOPCon (~22.3%). The average solar module in 2023 was about 21.6% efficient, up from 15.4% (a now-obsolete multicrystalline design) in 2012.

That’s a pretty big increase!

Anyway, speaking of the cost declines, they just keep on happening. In 2021 there was a sudden small increase in solar costs, causing some people to think that the era of learning curves was over. But it was just a temporary bump from temporarily higher materials costs in the wake of the pandemic. Chase notes that costs have come back down:

In October 2021, when the standard mono module price was 27.3 US cents per W, I said it would "come back down over 1-2 years" (referring to all-time low of 19 cents in summer 2020). Since it’s now 13.6 US cents in normal markets (ie not the US or India), not too bad a call.

As for whether levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a good measure of costs, Chase drily notes that it’s pretty much the only measure of cost that matters to utilities on the margin:

By the way, LCOE is just a fancy way of saying "the price you gotta pay someone for power to get them to build a power plant".

Of course, if you keep building lots and lots of solar, eventually intermittency starts to matter more. Chase explains that this intermittency will manifest as low or even negative electricity prices during the sunniest parts of the day:

After grid and land issues, the next big challenge for PV will be power price cannibalization. Basically, solar plants in one area all generate at the same time. This means that they reduce the price of power at that time, “cannibalizing” their own revenues…High solar penetration resulting in power price cannibalization also affects other power plants, but not as much as it affects solar, because solar plants generate most at times when solar is pushing the price down most. This will inhibit further solar build…By 2030 most countries will have spot power prices of zero for a few hours every sunny day.

Intermittency doesn’t really matter when you only build a modest amount of solar. But when you build an absolutely huge amount, like we’re expected to do in the near future, it starts to bite a lot. But Chase is optimistic that batteries are going to be a pretty effective solution to that problem:

It may well be that "negative power prices for a few hours every sunny day, followed by high evening power prices when the sun goes down" is a problem solved by capitalism and batteries…Utility-scale batteries became a thing much faster than I expected. @YayoiSekine’s team recorded 16.8GW/32.9GWh of gross energy storage capacity additions worldwide in 2022, and expect 41.9GW/98.6GWh in 2023.

Anti-solar people also claim that solar won’t have enough land to build on. This is probably an issue for wind, but for solar, Chase thinks it’s not that big of a deal:

There is enough land for lots of solar. There are enough golf courses in the U.S. for about 370GW, ffs. There’s also loads and loads of roofs…

So anyway, that’s all very optimistic stuff, and you should be optimistic too! Solar, together with batteries, looks like the first major step-up transition we’ve gotten in electric power generation technology since the advent of coal itself.

5. What’s destroying the humanities?

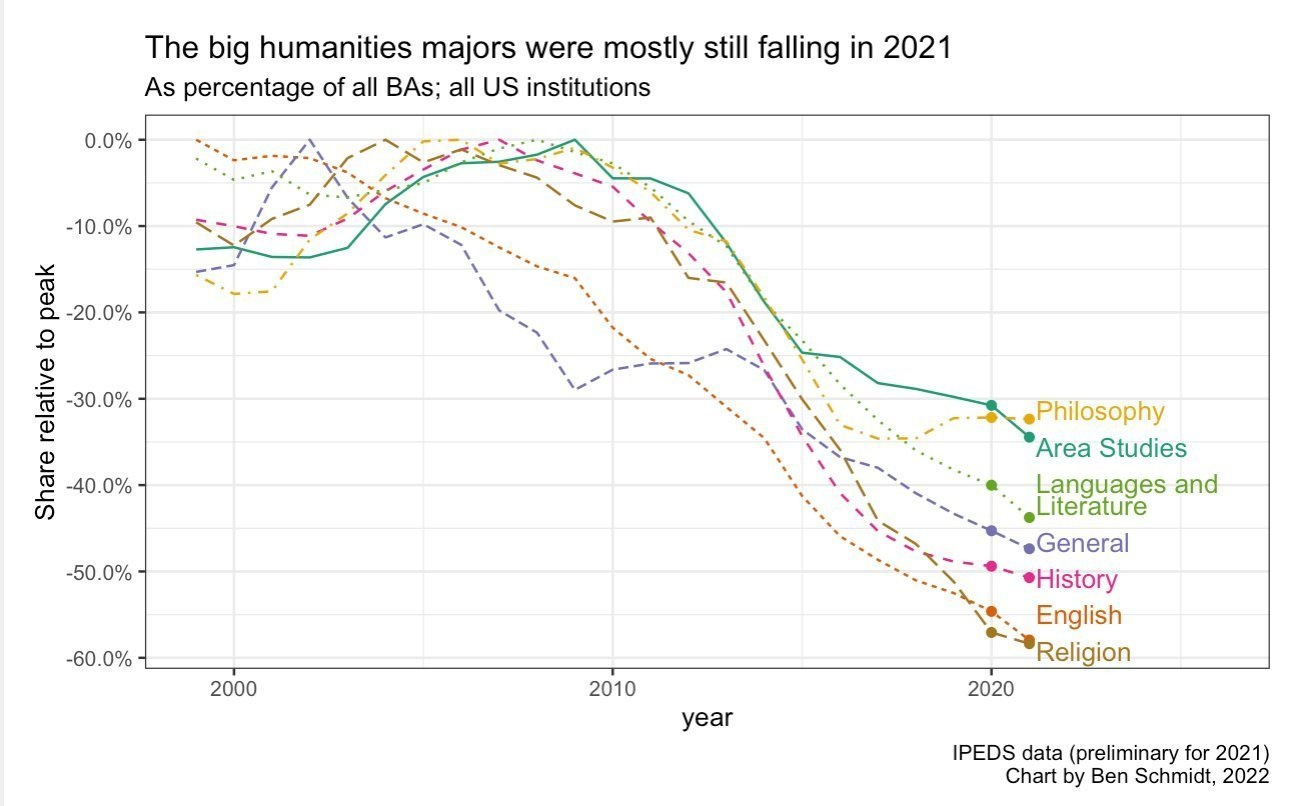

A bunch of people got upset when it was reported that the University of North Carolina system will now give out distinguished professorships only to scholars in STEM fields, and not to professors in the humanities. Some took it as a sign of the “dismantling of public higher ed in the USA”. I’m not so sure it means that much, but I do think it’s very likely that the shift away from an emphasis on the humanities will continue. The reason is that undergrads just don’t want to major in these subjects anymore:

The hard, cold fact is that while professors tend to see themselves as scholars first and educators second, from a university’s perspective, they are primarily instructors; if there aren’t as many students to instruct, fewer profs are needed.

Why are humanities majors (except for philosophy) in a state of collapse? My typical go-to explanation for this is economic — these degrees are less useful for getting a high-paying job, which is why we see students majoring in computer science, health, business, and other practical stuff more. And the timing lines up with the Great Recession, which strongly implies that once economic constraints started to bite, America’s youth became less eager to take a four-year voyage of intellectual pleasure and more focused on grabbing the brass ring.

But Bates College prof Tyler Austin Harper believes that the humanities have shot themselves in the foot by being “nakedly ideological”. He writes:

[W]e've created the conditions for what's going on at UNC. How did anyone think we could get away with being nakedly ideological for years without any chickens coming home to roost?..Universities have always been tacitly left-leaning and faculty have always been openly so, but institutions have never been this transparently, officially political. Almost every single job ad in my field/related fields this year has some kind of brazenly politicized language…

An example. Here's language from a current lit job ad: "We see this position as building on recent hiring in the English department in decolonial and anti-racist pedagogies and practices as well as a recent cluster hire in research related to diversity, equity, and inclusion."…Imagine if a public university job ad instead read: "We see this position as building on recent hiring in the English department in traditionalist pedagogies and practices as well as a recent cluster hire in research related to pro-life ethics, nationalism, and family values."

…This is about universities shamelessly embracing, as their official institutional posture, an openly ideological framework/stance.

Color me skeptical. While I do think that conservatives and red-state politicians are very mad at this ideological shift in humanities academia — and I agree with Harper that they have a right to be upset — I doubt that this is driving kids’ desire to avoid these majors. Young people are the ones who choose what to major in, not Republican politicians, and the young generation has a lot of lefties. I doubt very much that faculty job descriptions with “diversity, equity, and inclusion” in their names are what’s making kids avoid history and English majors like the plague.

Instead, my guess is that the ideological shift in humanities academia is more an effect of the sector’s shrinkage than the cause of it. As all the money and opportunity in humanities academia dries up, people who care about living a decent life and having a well-paying job drift away from the profession. Who does that leave in humanities departments? People who obsessively love their research, of course, but also committed ideologues. So those ideologues will have proportionately more and more sway over hiring and over the culture of the field as a whole.

Of course, humanities departments that become more ideological may be more likely to provoke conservative officials to cut their budgets more. But I think the collapse in humanities majors has to be regarded as the likeliest culprit for the shift here. So although I’d personally like to see humanities departments be less ideological, I doubt this will save them from decline. The only thing that will save them, I predict, is if the U.S. economy returns to a state in which young people are confident that they can get a good job no matter what they major in.

So basically, humanities profs who want to save their fields should be strong proponents of a pro-growth economic agenda.

While I agree strongly with the sentiment that we need to invest in our defense industrial base, the PLA Navy isn't adding submarines quite that fast. The PLAN has received 21 Yuan submarines in total, up four from last year's number of 17.

This being my area of study I can tell you undersea warfare is one of the PLA's worst domains. That does make it concerning their still clocking four boats per year because it means they're fighting to catch up, but it's not 21 boats per year.

As to the collapse of The Humanities... I don't think The Humanities have fully reckoned with their origin story. At least amongst the competitive colleges and universities that graduate most of our leaders, The Humanities have always been at the center, in terms of intellectual life, but also graduation requirements and so forth. But why?

The early 19th century saw the transformation of the colleges that did exist from primarily training religious leaders into a more broad-based liberal arts education that ended up in large part being finishing schools for the wealthy. As such, they delivered the sort of education that the upper classes wanted, which emphasized lofty, theoretical, and impractical studies and looked down on practical knowledge. (This mindset is humorously detailed in Paul Fussell's book "Class." Or in the scene in the film "The Aviator" when Howard Hughes meets Katherine Hepburn's family.)

Then, when higher education started expanding in the late 19th century, the people who were available to lead all the new colleges, to teach the classes, to design the curricula, were all products of the system that emphasized the impractical knowledge. Thus the Humanities-centric knowledge-for-knowledge's sake, life-of-the-mind model was replicated at all new institutions of higher learning, even the large Morrill Act state schools.

We are still living with the consequences of centering Higher Ed around the desires of the mid-19th-century upper classes. Familiarity with difficult literature and The Classics in their original Greek and Latin distinguish one as an educated in a way that knowing how an engine works doesn't. In Universities, he more theoretical math, physics, biology, and chemistry departments clustered in Schools of Arts and Sciences, whereas (practical and vulgar) schools of Engineering and Agriculture are separated off.

Justin Stover gave a reasonable assessment of the situation in a 2017 article for American Affairs. Here in the 21st century, the cultural preferences of the pre-WWII upper classes continue to fade away and it is no longer self-evident that a Humanities-centric degree is an essential step in becoming part of the nation's elite. And The Humanities have tried to argue that they are "essential" and of the importance of "asking big questions," but increasingly nobody believes it.