At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#12)

The college shakeout, China vs. its developing neighbors, Chinese zombie companies, more fun YIMBY stuff, and the victory of the Melting Pot

My weekly roundup comes slightly late these days, as I am dealing with another rabbit health problem; my remaining rabbit, Giggles, has a herniated disc in his back. This is the unfortunate drawback of adopting rescue rabbits who grew up in poor conditions, especially when they start getting old. Anyway, we’re working to rehab him to a speedy recovery.

We begin this week’s roundup, as always, with podcasts. This week’s episode of Econ 102 with Erik Torenberg is all about the Chinese economic slowdown. Here’s a Spotify link:

And here are Apple and YouTube.

Anyway, on to this week’s roundup. I’m at least temporarily switching these to un-paywalled.

1. The college shakeout and the market forces behind it

For many years, I touted expansion of universities as a solution to many of the problems that afflicted the U.S. — regional economic disparities, low innovation, and even social problems. But over the last few years, I’ve started to realize that this just isn’t going to work. The reason is shrinking demand; the number of young people in America has plateaued, and college enrollment rates are falling. Shrinking demand is leading to lower prices — tuition falling in real terms — and also to college closures. The most recent example is Alderson Broaddus University in West Virginia, which is closing down due to massive financial difficulties. The shakeout is also beginning to hit lower-ranked state schools — West Virginia University is cutting faculty and programs.

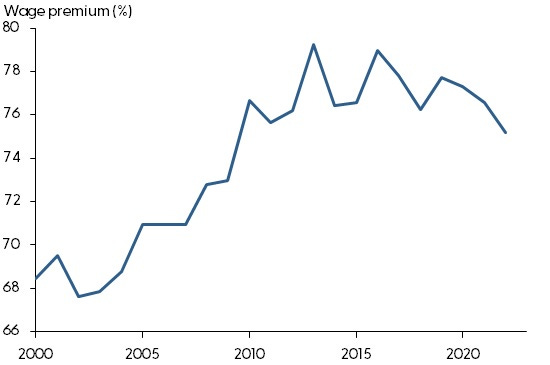

Some political shouters are certain to jump on this trend as justification for their negative opinions of “woke” American colleges. But I think the biggest factor is probably just that college isn’t as good a financial deal as it used to be. As if to underscore this point, the San Francisco Fed has a new analysis documenting the falling college wage premium. The premium plateaued in the 2010s and is now headed downward.

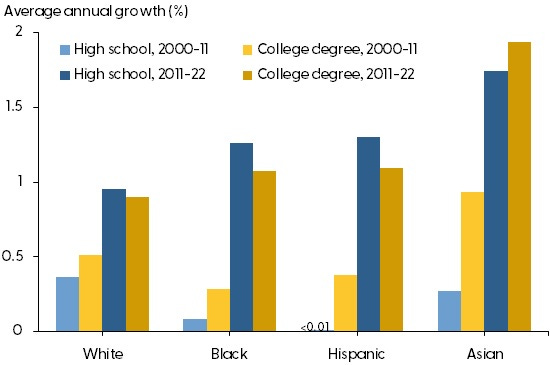

The drop is happening across racial groups.

Before we jump to the conclusion that this is bad news, though, we should realize that one big reason for the drop is that working-class incomes have been rising faster than the incomes of the college-educated over the last decade:

It’s too early to tell, but it’s possible that the financial crisis of 2008 and the recession that followed marked the end of a 30-year-long Age of Human Capital, where knowledge industries dominated everything else and you needed a degree to flourish. If so, that’s good news for economic equality in the U.S., but bad news for universities, who have benefitted enormously from the key role they play in the knowledge-industry economy.

Of course that’s just bad news on the margin — overall, universities will remain one of our nation’s key institutions, and demand for spots at good schools will remain very high. But I’m now pessimistic that a massive expansion of the college sector is the medicine that can save declining regions of the country.

2. China isn’t making many friends among developing countries

The BRICS summit convinced some people that China is on a successful charm offensive; even though BRICS is fundamentally fake, the fact that a number of countries want to be in this fake club could signal that they see China as a benevolent hegemon. China’s foreign ministry has been trying hard to push the idea that China is the leader of the world’s developing nations.

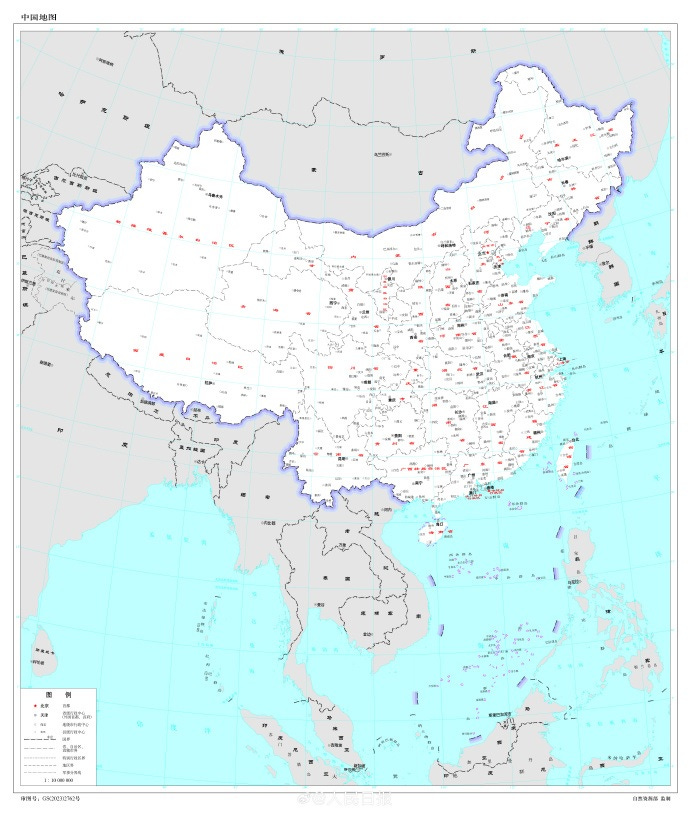

But at the same time, China has been engaging in actions that are enraging and alienating the developing countries in its own region. For example, it recently released a “standard map” of China that includes pieces of India, Bhutan, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines (as well as pieces of Russia, Japan, Brunei, and of course all of Taiwan).

It turns out — surprise! — that most countries don’t like it when you claim their territory as your own. So Vietnam has protested China’s map, as have India, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia. As Tanvi Madan and many others have noted, territorial expansionism is not exactly the way to win friends and influence people.

And China is increasingly signaling that these expansionist territorial claims are not just rhetoric on paper, but claims that it intends to actively pursue. The Chinese Coast Guard is water-cannoning Vietnamese fishing boats near Vietnamese islands that China claims, and sending ships into Vietnamese waters. These are exactly the “salami slicing” tactics that China has been using against the Philippines, except that the Philippines has its ally the U.S. to back it up. Vietnam is on its own, which is probably why it’s keen to sign a strategic partnership agreement with the U.S. when Biden visits the country next month.

In any case, it’s clear that China’s expansionist stance takes precedence over any diplomatic initiative to paint themselves as the leaders of the developing world. Perhaps a few countries in Latin America or the Middle East — far from Chinese warships, and still bitter over America’s legacy of interventionism there — will buy it. But in Asia, the world’s key strategic region, they will not.

3. Will China’s economy be hobbled by “zombie” companies?

Back when the country’s growth was still strong, there was not as much of an audience for pieces criticizing China’s economic model; now that it’s suffering what is likely a long-lasting slowdown, everyone is rushing to explain where it went wrong. Brad DeLong and Dan Drezner have good roundups of many of the pieces that are being written. All of them are good and deserve a read.

But Arpit Gupta’s post is probably the most unique, because it raises some issues that I haven’t actually seen many people talking about before (and which I was planning to write about, before Arpit beat me to the punch!).

(First, a brief correction. Arpit associates me with two views of China’s slowdown: the “authoritarian expropriation risk” view, and the “real estate boom-bust” view. The second one is correct; I do think real estate is the main cause of China’s current slowdown. But although I wrote a popular article about China’s tech crackdown back in 2021, I don’t think it was a major cause of the slowdown; it was really just an illustration of how Xi Jinping thinks, and of why he’s not very competent.)

Anyway, Arpit has his own explanation of China’s slowdown, which is what he calls “soft budget constraints”. This is a polite term for what most economists call “zombie companies” — the idea that if failed companies are kept on life support, they end up lowering productivity. They do this both by distorting incentives (if you know you can’t fail you won’t build an efficient business) and by hogging resources and market share from more productive companies. Arpit argues that this is what’s going on in China:

You end up in a chronic situation of “shortages,” because firms all get bailed out, and continue operations as zombie entities (and demanding more inputs) long after financial viability. And the Party can never commit to doing the hard market reforms here, which would inevitably lead to ending political rule.

Okay, what evidence is there for this in China?

Looking across manufacturing firms, TFP is down substantially in the post-GFC window driven by two factors. First, TFP growth of new firms is down a lot, suggesting that firm entry has become less dependent on purely economic factors. Second, we see the TFP growth from the exit dimension is negative — improving productivity by removing unproductive firms isn’t happening in China.

Arpit sees zombification as a feature of communist economies, but while communism probably makes it a lot worse, zombification is a well-known story that has plagued other countries as well. Caballero, Hoshi and Kashyap have a great 2006 paper explaining how banks in Japan were incentivized to “evergreen” loans to loss-making companies in the 90s, resulting in an overgrowth of zombies that hogged labor and capital and market share and basically prevented Japanese entrepreneurs from building a new crop of more efficient champions. And although Japanese banks mostly no longer do this, the Japanese government stepped in in the 2010s with a bunch of bailout funds that rescue inefficient companies from bankruptcy simply in order to preserve high employment levels.

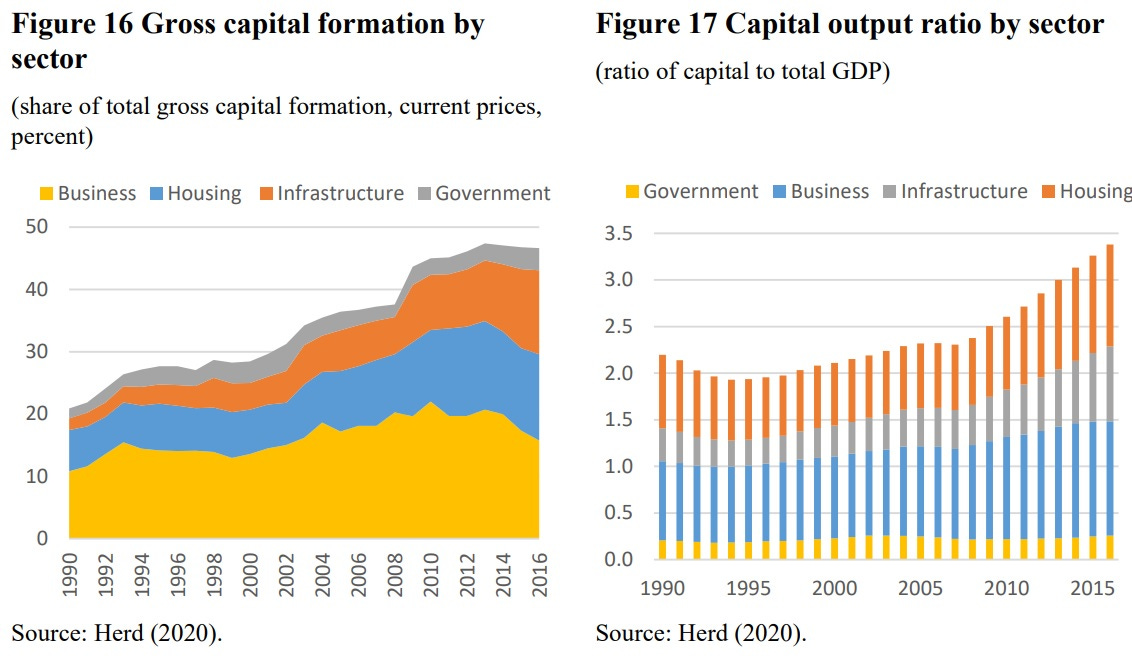

In terms of what caused China’s current slowdown, I still place the lion’s share of the blame on real estate. The same 2020 World Bank report where Arpit got that productivity graph shows that the business sector as a whole has been responsible for only a small piece of the increase in the incremental capital output ratio (i.e. the increasing amount of investment needed to keep growth going) in recent years. Most was due to housing and infrastructure becoming less efficient even as they hogged more capital from the business sector:

(Quick note to the World Bank: What kind of maniac rearranges the color scheme on two adjacent graphs with the same sectoral breakdown? Chart crime!)

But I do believe that zombification was a quietly building trend in China all this time, and that it’s likely to be a bigger problem going forward. Along with aging, the end of urbanization, and international backlash against Chinese industry, it’s going to be one of the headwinds that prevents China from returning to developing-country growth rates long after the real estate problems are cleaned up.

4. YIMBY victories in the battle of ideas

The most encouraging grassroots political movement in the country in the last few years has been the YIMBY movement, which concentrates on a concrete goal (building more housing) instead of a political ideology. In recent years they’ve won a number of legislative victories, and the trend seems to be accelerating. I plan to keep reporting on the trend as it continues

Just as important as the legislative battle, in my view, is the public relations battle, which YIMBYs are also winning. The pernicious effect of single-family zoning on housing construction has gone from a fringe belief to conventional wisdom. And despite shrill shrieks on the app formerly known as Twitter from “leftists” who think that boosting housing supply represents a form of “trickle-down economics”, the Biden administration is now firmly on board with the need to increase supply.

Meanwhile, YIMBYs are also winning the intellectual battle, as a continuous flood of new studies pours in that supports the notion that building more housing leads to broadly shared prosperity. For example, a study on city-wide upzoning in Auckland, New Zealand found that upzoning strongly increased construction. We don’t yet know the effect on rents, but this is encouraging because it shows that it’s possible to get more housing supply simply by allowing it to be built. Meanwhile, a study by Liang and Kindström finds that new housing construction benefits people of all income groups:

Newly produced homes are often expensive and it is also largely people with higher incomes who move into them…Can newly built housing create moving chains that free up housing even for people with lower incomes?...Our results show that the benefit of new housing is evenly distributed between residents from different income groups. Although it is primarily people with high incomes who gain access to new housing, these homes create a ripple effect and indirectly improve housing options for people with low incomes. One of the explanations is that people with lower incomes move more often than people with higher incomes, which means that they more often participate in moving chains and take advantage of vacancies created by new housing, says Che-Yuan Liang.

This is exactly the effect that YIMBYs call “filtering” and anti-YIMBYs vilify as “trickle-down”, and which I call the “Yuppie Fishtank” effect.

By this point, we’ve also had the opportunity to observe the few American cities that have actually made a concerted effort to allow more housing. These include Arlington, VA, Seattle, and Minneapolis. Their attempts have been much more modest than what was done in Auckland or Tokyo, of course, but they’re still encouraging.

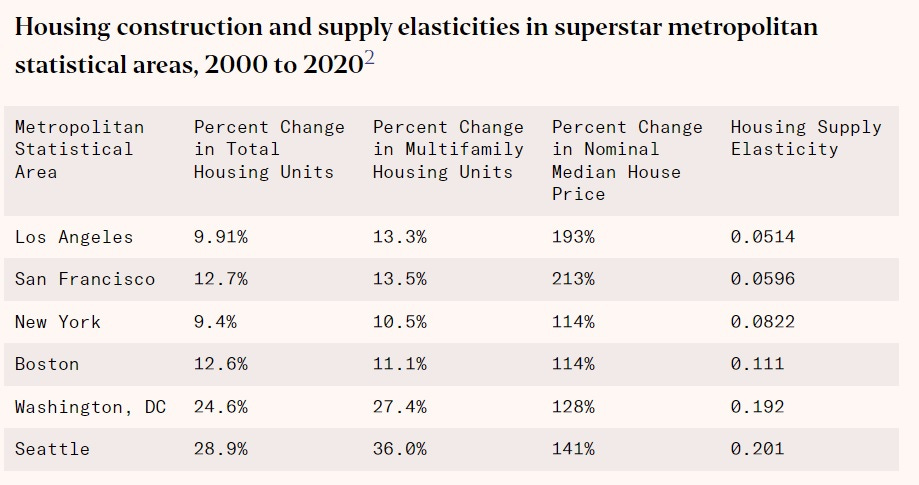

Emily Hamilton has an amazing essay at Works in Progress in which she explains both the policy and the politics of Arlington’s homebuilding efforts. I heavily recommend reading the whole thing. One interesting tidbit is that Arlington basically made a deal with rich NIMBYs, allowing them to preserve small islands of low density in exchange for them supporting upzoning throughout the city. That’s the kind of grubby, unfair, “how the sausage gets made” detail that gets lost in many of these discussions, but given how entrenched and powerful NIMBYs are in America, some cities may find these details useful. Anyway, Hamilton shows that the D.C. metro area (which includes Arlington) and Seattle have built more multifamily housing and experienced a higher “supply elasticity” than other big “superstar cities” — prices still went up because a lot of people moved in, but prices went up less relative to the population increase.

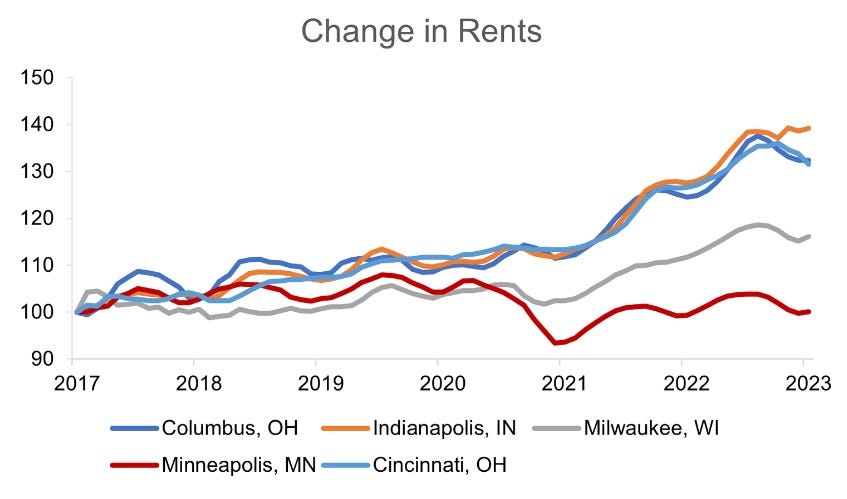

Another excellent post that I heavily recommend is Matthew Maltman’s analysis of Minneapolis’ housing reforms. He argues that although the much-trumpeted abolition of single-family zoning has had only modest effects, it’s one of a large package of reforms that have had a significant effect on supply. And he notes that rents in Minneapolis have come down relative to nearby cities since these reforms went into effect:

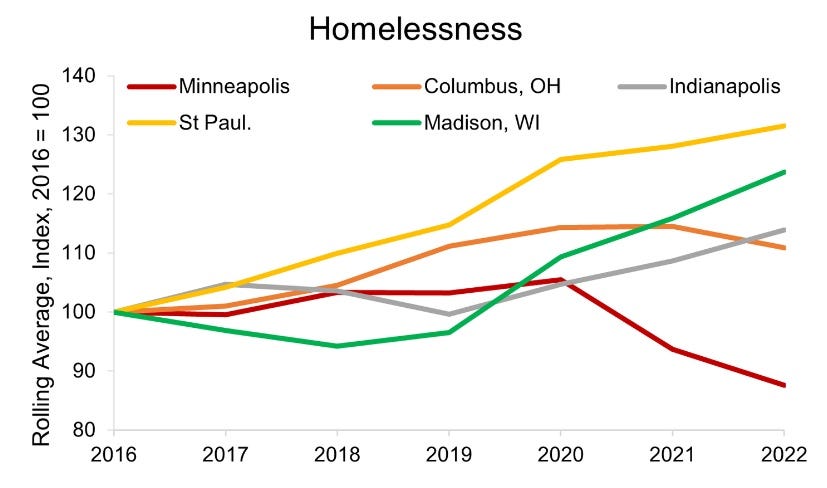

And lest you think that this was an effect of the riots in Minneapolis in 2020, it’s also the case that homelessness has fallen there as well:

Anyway, it’s going to take a lot more of these intellectual and P.R. victories before YIMBYism can overcome the NIMBYism that has become entrenched in America since the 1970s. But the trend line seems clear.

5. Integration works, the Melting Pot is real

Over at Marginal Revolution (which just celebrated its 20th anniversary!), Alex Tabarrok flags some new research from Indonesia on the effectiveness of integration at creating a sense of national identity. Obviously this is a big issue for Indonesia, since it’s a sprawling, highly diverse collection of at least 17,500 islands. Here’s the original paper, by Bazzi et al. (2019). And here are some excerpts from Tabarrok’s summary:

[Indonesia’s] transmigration experiment moved millions of people from the more densely populated islands to the less densely populated islands. The policy was big, between 1979 and 1984, for example, 2.5 million people were moved.

One goal of the program was to relieve population pressures and give more Indonesians their own plot of land but another goal was the creation of a unified nation…The program was voluntary. Migrants received plots of lands assigned by lottery in new villages….The migrants could not choose their new village. Thus, the new villages varied [randomly] in diversity…

The authors show that people who for random reasons ended up in villages with a high [ethnic] fractionalization adoped more “national” or “unifying” behaviours. For example, people in high fractionalization villages were more likely to adopt the national language as the language spoken in their home (as opposed to speaking their mother tongue at home). In addition, the people in high fractionalization villages were more likely to intermarry and to give their children less ethnic names. Measures of social capital such as trust, tolerance and public goods provision were also higher in high fractionalization villages.

Note that this is different from the Contact Hypothesis, which predicts that integration reduces prejudice. There’s pretty good evidence that the Contact Hypothesis is usually true (though not in all cases). But Indonesia’s experience shows that integration does something else as well — it binds people together into a shared national identity.

Now, for people who think that the idea of America as a “Melting Pot” is a microaggression, this is not necessarily good news. There is a viewpoint that multiculturalism should be about preserving ancestral ethnic differences rather than mixing cultures. And from what I can tell, this viewpoint is associated with a general outlook of anti-patriotism — the opponents of the Melting Pot tend to take a dim view of American national identity as a whole, and tend to look at America as a fundamentally racist entity. So if you have this general attitude, the news that integration fosters a unifying national identity might lead you to support carving out homogenous racial “spaces” in order to prevent that unification. And in fact we do see a few scattered examples of this.

But the far, far bigger threat to American national integration isn’t “woke” ideology — it’s the geographic segregation that still defines American cities. And the fight for more housing density and better public transit — the YIMBY fight — is partly a fight against that legacy. Research using GPS data shows that denser urban areas with better transit involve more contact between people of different races. It’s thus unsurprising that big cities are much more progressive.

In any case, America remains a grand experiment in diversity — an attempt at forging a powerful, effective, rich, free, happy nation from all the peoples of the world. If integration and the Melting Pot succeed, then America succeeds, and in some sense will have proven the fundamental unity of the human race.

The way I have often put it (including talking to voters as a candidate for local office) is that I think everyone that contributes in our community, whether it's a doctor or lawyer or engineer, or a barista or lawncare guy or teacher, should be able to find a place to live in our community. And that can't possibly happen unless you make it legal to build some smaller apartments, and let folks adapt their own properties to meet the needs of their families, like was legal up until the wave of '70s down-zoning. Make normal neighborhoods legal again!

https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2019/7/3/making-normal-neighborhoods-legal-again

Integration and diversity is a super power. The people who are against it are zero sum gamers (and probably racists) who think if other people win they lose. We should be optimizing for win-win