At least five interesting things for your weekend (#32)

The bridge disaster, Daniel Kahneman, Biden and nuclear power, ebbing unrest, Bay Area "progressives", and cancer detection

If you happen to be in Tokyo right now, and you’re free this Saturday (3/30), feel free to come to my hanami party! It’s from 1:00 to 5:00 PM in Yoyogi Park. We don’t have a spot picked out, but we’ll probably be right around here. I’ll tweet an exact location from my Twitter account when we’re set up. Oh, and please bring your own snacks and drinks! Anyway, the cherries are very late this year, but hopefully they’ll be out by Saturday.

Anyway, I have a couple episodes of Econ 102 for you this week. Erik and I tried out a fun new format, where he asks me about the economies of various countries, and I give him a quick answer about their current situation. We’ve done two of these so far, and we’re going to do one more:

On to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. What should we learn from the Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse?

The country recently watched in horror as a cargo ship crashed into one of the support pillars of the Francis Scott Key bridge in Baltimore, collapsing the middle section of the bridge and causing six deaths:

Lots of people took the opportunity to blame the accident on their favorite political bogeyman, or to promote various conspiracy theories. But the fact is, sometimes accidents happen. We should try to minimize them, by implementing safety procedures, by improving our infrastructure, etc. But they are going to happen, nevertheless. And it’s important to maintain perspective — in recent decades, transportation disasters haven’t become more common:

Note that this also applies to airplane crashes, which a lot of people have recently been anxious about, following the well-publicized problems with the Boeing 737. Not only have fatal air incidents remained rare, but really serious crashes have become even rarer than before:

Instead of using the bridge disaster to fuel conspiracy theories or political feuds, I think we need to draw two important lessons for the future.

First, U.S. infrastructure is more vulnerable than many people realize. Recently, security services have been sounding the alarm about Chinese hackers targeting U.S. critical infrastructure:

Christopher Wray on Sunday said Beijing’s efforts to covertly plant offensive malware inside U.S. critical infrastructure networks is now at “a scale greater than we’d seen before,” an issue he has deemed a defining national security threat.

Citing Volt Typhoon, the name given to the Chinese hacking network that was revealed last year to be lying dormant inside U.S. critical infrastructure, Wray said Beijing-backed actors were pre-positioning malware that could be triggered at any moment to disrupt U.S. critical infrastructure.

“It’s the tip of the iceberg…it’s one of many such efforts by the Chinese,” he said[.]

That’s legitimately terrifying. Everything in the U.S. is networked these days, and almost everything uses Chinese-made electronic components of some sort. China also makes most of the world’s ships. It’s easy to imagine dozens or even hundreds of disasters like the Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse happening on the day that China attacks Taiwan. So we should harden both our cyber infrastructure and our physical infrastructure as best we can, in preparation for that day.

Second, efforts to rebuild the Francis Scott Key Bridge are going to tell us a lot about U.S. state capacity. President Biden has pledged financial assistance, but that doesn’t mean the repairs will be done on time or cheaply. The recent rapid repair of a collapsed section of I-95 in Philadelphia shows that some regions of America still have high state capacity; the bridge collapse will test Baltimore’s. The whole country (and the world) will be paying attention.

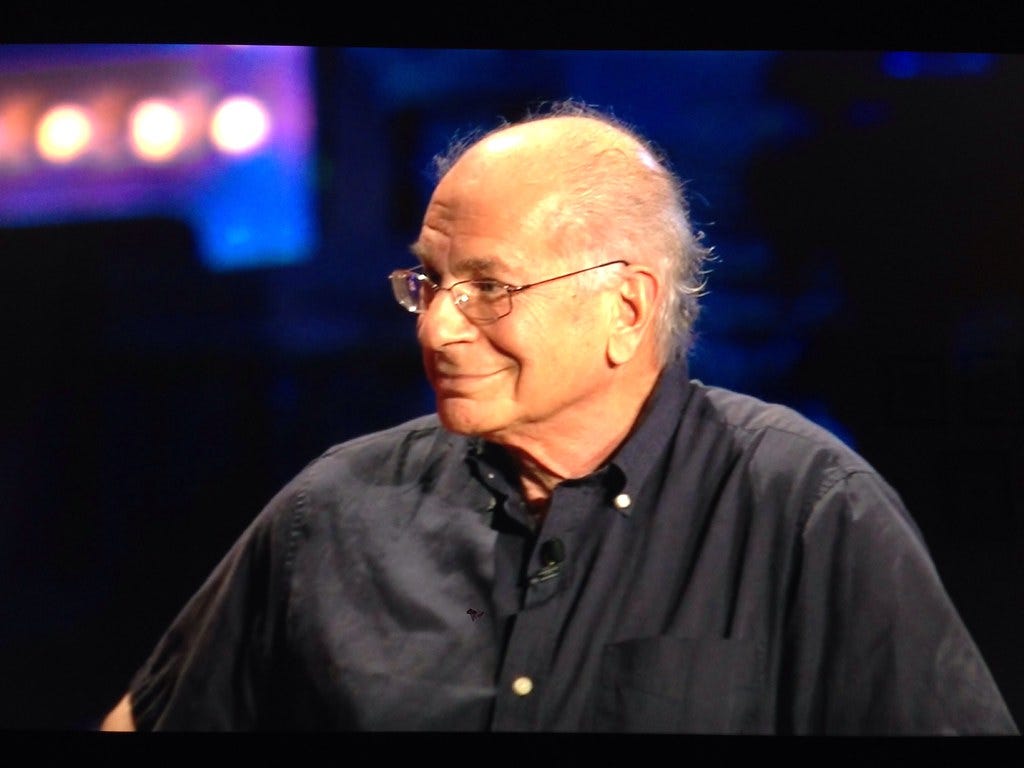

2. Daniel Kahneman, R.I.P.

Daniel Kahneman has just passed away at the age of 90. Although he was a cognitive psychologist, he was best known for being the father of behavioral economics, which won him a Nobel in 2002.

Kahneman did his pioneering econ research in the 1970s and 1980s. At that time, economists really took individual rationality seriously; they viewed the hyper-rational “agents” in their models not merely as convenient mathematical approximations, but as descriptions of actual human behavior. So when a psychologist came along and started showing that humans didn’t actually behave like the agents in those models, it came as a giant shock to the foundations of the entire economics discipline.

Kahneman basically did a bunch of psychology experiments to show that human beings are bad at probability. He and his longtime coauthor Amos Tversky (who died before he could share the Nobel) showed that people make strong inferences from very small samples — for example, if you meet two nice people from Australia, you might conclude that Australians are nice in general. Kahneman called this the “law of small numbers”.

This is just one example of a more general family of fallacies called “representativeness” fallacies, which Kahneman’s experiments explored in depth. Another famous example is pattern-matching — if math professors tend to wear glasses, and you had to guess whether someone is a math professor or a waiter based on whether they wear glasses, you might guess they’re a prof. But there are a lot more waiters than profs, so your guess is a bad one — you’ve committed the statistical sin of base rate neglect.

I could keep listing examples, but you get the point. Kahneman discovered a huge number of these common human mistakes. By the time he was done, there was no doubt that human beings don’t really resemble the homo economicus of 1970s models. There are exceptions, of course — companies bidding on Google ads in online auctions tend to act pretty rational. But after Kahneman, economists always had to accept the possibility that behavioral biases might drive a wedge between their predictions and the empirical data.

That understanding helped drive the rise of empirical economics, which has been the big change in the econ field over the last three decades. There are many other reasons that econ theories need to be checked against data, but economists had put so much emphasis on rationality that a demonstration of persistent, general, predictable irrationality was an especially effective method of forcing them to think about empirics.

Ideally, though, we’d want behavioral economics to give us more than just a list of anomalies. If humans are predictably irrational, we should be able to come up with a theory that describes their irrationality. Kahneman came up with psychological theories, about where irrationality comes from in the human mind — you can read about these in his book, Thinking Fast and Slow. But he also came up with an economic theory, describing how irrationality affects decision-making. This was called prospect theory.

Prospect theory is basically a combination of two behavioral biases — loss aversion and overestimation of small probabilities. Laboratory evidence generally supports prospect theory, but applying it in the real world has proven to be very tough, for one big reason — it’s hard to know what counts as a loss in people’s minds. Do people measure gains and losses relative to what they had yesterday, what they had a year ago, or what they expected to have? It’s hard to predict.

But even though he didn’t manage to completely replace existing econ theory, Kahneman’s towering influence over the economics field is undeniable. He was an all-too-rare example of a social science researcher who can cross disciplinary boundaries and apply insights from one field to transform another.

3. Joe Biden supports nuclear power

Nuclear power is not going to be our main source of green energy. That will be solar (with batteries for storage). But nuclear is still important! First of all, we already have a bunch of nuclear plants already built; shutting them down, as Germany and New York did, and as California is now threatening to do, is absolute madness in the face of the climate crisis. And nuclear is a helpful source of “clean firm” power to replace that last bit of natural gas. Environmental groups have been foolish to oppose nuclear power.

Meanwhile, every President, Democrat or Republican, pays lip service to nuclear power and then does little to support it. Trump did commit a bit of money to nuclear energy research, but not much to support the existing industry.

But Joe Biden and his administration are pragmatic and sensible. They are industrialists first and foremost. So Biden is actually doing something real and tangible to support nuclear power:

As part of President Biden’s Investing in America agenda, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) through its Loan Programs Office (LPO) today announced the offer of a conditional commitment of up to $1.52 billion for a loan guarantee to Holtec Palisades to finance the restoration and resumption of service of an 800-MW electric nuclear generating station in Covert Township, Michigan. The project aims to bring back online the Palisades Nuclear Plant, which ceased operations in May 2022, and upgrade it to produce baseload clean power until at least 2051…

“Nuclear power is our single largest source of carbon free electricity, directly supporting 100,000 jobs across the country and hundreds of thousands more indirectly,” said U.S. Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm. “President Biden’s Investing in America agenda is supporting and expanding this vibrant clean energy workforce here in Michigan with significant funding for the Holtec Palisades nuclear power plant." (emphasis mine)

If you are a supporter of nuclear power, you should give Biden credit for this.

Now, it’s not year clear if this is a one-off measure, or a sign of a general turn by the administration toward supporting nuclear plants across America. Nor is it clear whether the administration will be willing and able to push through permitting reform, which is necessary for building nuclear as well as solar. But this is an important start. And if you’re a nuclear advocate, you should give credit where credit is due, in order to encourage more of the same.

4. Small signs of the ebbing of unrest?

I called the top on America’s age of unrest pretty early — all the way back in mid-2021. Since then, I think events have broadly been consistent with that call, though of course a disputed election or the election of Trump could upend things later this year. But anyway, I continue to see small signs that unrest is beginning to subside just a little bit.

For example, people are looking at news websites a lot less than in February 2020 (which was before the pandemic had fully struck). And traffic to right-wing websites, both fringe and mainstream, is down by even more:

On the left, the viewership of major leftist streamers like Hasan Piker appears to be in decline as well.

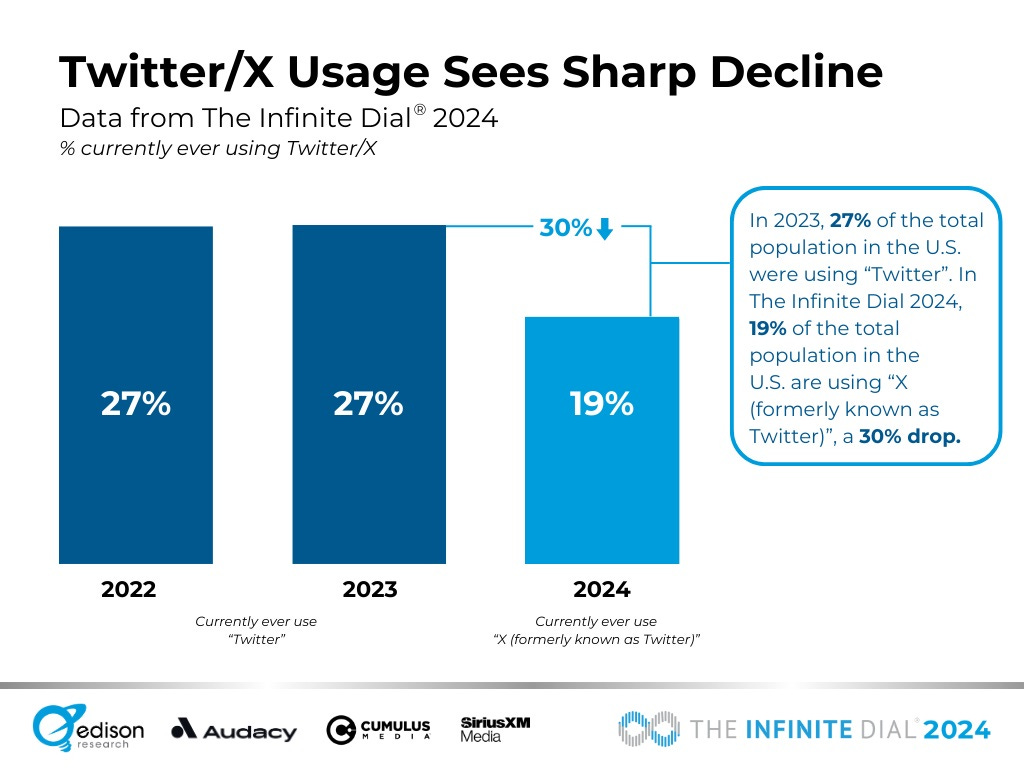

And Twitter/X, the shoutiest platform of all — the epicenter of 2010s unrest — is showing declining usage. Here are two different recent studies showing the exact same thing:

But remember that as unrest ebbs, activism becomes more extreme even as it shrinks. This is because the more reasonable people leave activist movements first, and the people who remain are a more extremist sample — and are now free from the restraining influence of the departed moderates. So that’s why we see turmoil among rightist activists:

Rufo, a fairly mainstream activist, is referring to the wave of antisemitic rightists attacking right-wing media figure Ben Shapiro.

Meanwhile, on the left, Palestine protests were never that common and have become even rarer, but many have become openly antisemitic and aggressive, and leftists have embraced openly Islamist figures who express hatred for gays.

But even as the activists on both sides become increasingly wacky, mainstream culture shows a few signs of becoming more chill and laid-back, just as it did in the 1970s.

5. Bay Area “progressives” doing very un-progressive things

There’s a reason I put scare quotes around “progressive” when I talk about the San Francisco Bay Area. It’s because so many of the things they do would be counted as conservative, or even reactionary, in other regions of the country and the world. Bay Area “progressives” have become adept at cloaking policies like excluding poor people from rich neighborhoods and weakening public education in the language of social justice and equity.

One prime example is housing policy. Aaron Peskin, a longtime SF supervisor, notorious power broker, and candidate for mayor, recently proposed a bill to downzone properties along a certain section of San Francisco’s waterfront. When Mayor London Breed vetoed the bill, the Board of Supervisors — which is currently controlled by Peskin’s allies — overrode the veto.

The area in which Peskin successfully blocked multifamily housing development currently consists of a bunch of commercial buildings and parking lots along the waterfront. Local YIMBY activist Max Dubler was kind enough to draw a diagram:

Dubler cynically notes that some of Peskin’s rich constituents might have had their beautiful views blocked by affordable housing for middle-class San Francisco families. We can’t have that, can we?

Others noted that Peskin himself owns multiple rental properties in the area, and that building housing nearby might obstruct those properties’ views — or, even more terrifyingly, result in the kind of people who qualify for affordable housing living near to Peskin’s properties. A cynic might argue that Peskin and the other SF “progressives” are trying to use NIMBYism as a type of public safety policy, promising to keep the poor people away, as an alternative to stepping up policing of the city. Peskin is not the only SF “progressive” who regularly votes to protect parking lots from turning into apartment buildings.

Anyway, the episode is particularly ironic given that Peskin recently approved increased funding for affordable housing. Some of that money will no doubt make its way into the pockets of well-connected nonprofit groups (this is how SF politics works), but Peskin is making sure that it won’t be spent on actual housing in his own district.

Anyway, if you want another example of Bay Area “progressives” behaving badly, look no further than the case of Jo Boaler, a British author currently teaching at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. As Armand Domalewski noted in a guest post last year, Boaler is the key important figure in the push to water down public-school math education in the name of “equity”:

Boaler’s ideas are bad, but she also has a history of questionable behavior. She once threatened to call the police on Jelani Nelson, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at Berkeley, after he criticized her publicly for charging $5000 per hour as a consultant (Nelson is Black, by the way). She also declared herself a “maths prof at Stanford” in her Twitter bio until recently, when a bunch of Twitter users pointed out that she has no affiliation with the Stanford mathematics department.

Boaler’s research has also been dogged with accusations of dishonesty. Sanjana Friedman reports:

[L]ast week [California Math Framework] got hit with what might be its most damning blow yet: a 100-page, well-sourced document published by an anonymous complainant alleging that many of the misrepresented citations throughout the CMF can be traced directly back to Boaler…

Other academics began ringing alarm bells about her dishonesty back in 2006, when a team of mathematicians accused Boaler of “grossly exaggerat[ing]” research she claimed supported heterogeneous classes…[W]hen three math professors (including James Milgram, a fellow Stanford faculty member) analyzed the larger dataset Boaler had selectively cited, they found the data actually supported the opposite of Boaler’s conclusion…

More recently, Brian Conrad, a professor of mathematics at Stanford, extensively documented misrepresented citations in the CMF, many of which have now been directly linked to Boaler’s research, thanks to the anonymous complaint published last week.

Friedman also drily notes that even as she fights to remove algebra education from middle schools, Boaler sends her own children to an incredibly expensive private school that offers middle-school algebra to all its students.

So anyway, this is what the Bay Area has to deal with — landlords who protect parking lots in order to keep poor people out of their neighborhoods, and education researchers who try to prevent public school kids from getting the same math education they buy for their own kids. With “progressives” like this, who needs reactionaries?

6. The future of cancer detection

The focus on AI’s creative abilities has temporarily drawn attention away from some of its other important use cases. One of these is detection; AI in some sense is a gigantic statistical regression, and gigantic statistical regressions are very good at detecting very faint signals in an ocean of noise. There are lots of things humankind would like to be able to detect better — killer asteroids, nuclear submarines, mechanical imperfections, dirt in a cleanroom, and so on. And, of course, cancer:

An AI tool tested by the NHS successfully identified tiny signs of breast cancer in 11 women which had been missed by human doctors…The tool, called Mia, was piloted alongside NHS clinicians and analysed the mammograms of over 10,000 women…Most of them were cancer-free, but it successfully flagged all of those with symptoms, as well as an extra 11 the doctors did not identify.

This is great news. As that article reports, early detection will allow lots of patients to be treated much more effectively and less invasively than if detection were limited to traditional screening methods:

Because her 6mm tumour was caught so early she had an operation but only needed five days of radiotherapy. Breast cancer patients with tumours which are smaller than 15mm when discovered have a 90% survival rate over the following five years…Barbara said she was pleased the treatment was much less invasive than that of her sister and mother, who had previously also battled the disease…Without the AI tool's assistance, Barbara's cancer would potentially not have been spotted until her next routine mammogram three years later. She had not experienced any noticeable symptoms.

This is going to do a lot to improve cancer survival rates, and reduce the harmful side effects of treatment. Next time you get the urge to set up a government panel to limit AI innovation in order to protect radiologists’ jobs (which, btw, are doing perfectly fine so far in the age of AI anyway), please think about the cancer patients.

But there’s something else I wonder about as I read stories like this one. If AI continues to get better at detecting tiny cancers, will there come a time when it starts detecting lots of cancers that are so tiny that it’s not worth giving people chemo to try to eliminate them? If that happens, people will have to do one of two things: A) find doctors who are willing to do chemo anyway, for peace of mind, or B) live with the anxiety of walking around knowing that they have a tiny spot of cancer somewhere inside them that could start growing faster at any time.

This isn’t actually that much of a hypothetical; doctors are already debating whether to reduce screening for prostate cancer, which is often slow-growing and easy to treat. One interesting idea is to just come up with a different name for the lowest-risk, slowest-growing forms of prostate cancer, in order to stop people from freaking out about having “cancer”.

In any case, the medical profession should probably start thinking about what to do in case rapidly improving AI creates a wave of overdiagnosis — not just for cancer, either, but for a variety of other diseases and disorders as well.

I don't want Biden to subsidize nuclear power by pouring money into it. I want him to remove the barriers which make the construction of new and novel nuclear power plants so ungodly expensive.

Build the damn Yuca mountain nuclear waste site. Give passively safe reactors fast tracked NRC approvals (it's incoherent to let existing designs continue to operate and go over inherently less dangerous new designs with a fine tooth comb). And, most importantly, limit the ability of opponents to use APA and EPA report and notice/comment requirements to hold up projects of all kinds (they aren't substantive requirements).

Besides, I want the nuclear people to get behind carbon taxes as their ticket to profits.

To what extent do wealthy SF "progressives" believe their own rhetoric? I'm personally a great believer in Hanlon's razor, so I'm inclined to think this is caused by self-deception rather than craven self-interest. Humans in general are very good at convincing ourselves that what is good for us is good for everyone.