At least five interesting things for your weekend (#41)

Soviet America (or not); the energy revolution; Trump's tax cuts; the Build-Nothing Country; macro data mysteries

A friend told me this week that he thinks of these roundups as “Wednesday roundups”. In fact, there’s no set day of the week — I just write one whenever I get enough things piling up that I need to do a roundup in order to avoid being driven insane by all the things I’m not writing about. But if you want to wait to read this roundup on Wednesday, I won’t try to stop you.

Anyway, first we have podcasts. I went on blogging legend Andrew Sullivan’s podcast, and talked to him about Cold War 2:

That was pretty fun! That was my first time talking to Andrew, and he was a lot buffer and had a much stronger British accent than I expected — kind of like Billy Butcher from The Boys, if Butcher were a conservative gay bodybuilder instead of a nihilistic revenge-obsessed terrorist. But anyway, we had a great conversation, so check it out.

Erik Torenberg and I have two episodes of Econ 102 for you this week. In the first, we go back to our roots and talk about interest rates and inflation and so on:

And in the other, we do a bunch of Q&A, and talk about various fun subjects:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. Despite a couple of parallels, the U.S. is not the USSR

Niall Ferguson has a widely read post over at The Free Press, in which he compares the current U.S. to the late-stage Soviet Union. Some excerpts:

But it only recently struck me that in this new Cold War, we—and not the Chinese—might be the Soviets…U.S. deficits [are] forecast by the Congressional Budget Office to exceed 5 percent of GDP for the foreseeable future, and to rise inexorably to 8.5 percent by 2054…Economists keep promising us a productivity miracle from information technology, most recently AI. But the annual average growth rate of productivity in the U.S. nonfarm business sector has been stuck at just 1.5 percent since 2007…

We have a military that is simultaneously expensive and unequal to the tasks it confronts…Gerontocratic leadership…Average confidence in major institutions is roughly half what it was in 1979…[Y]ounger Americans are suffering an epidemic of mental ill health…while older Americans are succumbing to “deaths of despair”…Life expectancy has declined in the past decade…

A bogus ideology that hardly anyone really believes in, but everyone has to parrot unless they want to be labeled dissidents—sorry, I mean deplorables? Check. A population that no longer regards patriotism, religion, having children, or community involvement as important? Check. How about a massive disaster that lays bare the utter incompetence and mendacity that pervades every level of government? For Chernobyl, read Covid. And, while I make no claims to legal expertise, I think I recognize Soviet justice when I see—in a New York courtroom—the legal system being abused in the hope not just of imprisoning but also of discrediting the leader of the political opposition.

I think it’s important for Americans to worry about our society’s problems, instead of letting them fester. And some of the problems Ferguson mentions — poor public health, lack of confidence in institutions, fiscal deficits, and the strains on the military — are very real. So it’s good for people to read pieces like this and to gain a sense of urgency about these problems.

But in his rush to equate America with the USSR, Ferguson throws in a number of talking points that don’t make sense:

He cites slow productivity growth as a sign of American dysfunction, despite the fact that productivity growth is even slower in other countries (including, probably, China). Remember, before you claim that a problem is due to unique failings of the American government, you should always look at other countries to see if they’re doing better.

Similarly, Ferguson cites Covid as a Chernobyl-level disaster. But while the U.S.’ performance in Covid was not especially great, it doesn’t really stick out on a map. To compare a global pandemic to a one-country nuclear accident is a big stretch.

Ferguson is quick to label Trump’s indictment in New York as “Soviet justice”. Again, he doesn’t compare to other countries. In fact, indictment of former leaders is pretty common in democracies.

Ironically, Ferguson’s list of problems misses some of America’s deepest dysfunctions. Most importantly, he overlooks the thicket of environmental review laws and local and state regulations that prevent housing, power plants, transmission lines, and factories from being built.

But despite some omissions, Ferguson’s litany of America’s ills suffers from excess breadth. When you throw weak points in with strong ones, some readers may be overwhelmed into buying into your thesis, but many will simply dismiss it. A more focused critique of America’s problems would have been a more effective one.

Ferguson also could have done more to acknowledge America’s very real strengths, and how these differ from the old USSR. For example, American consumers live the most lavish lifestyle in the world, bar none. Even in countries with higher GDP, like Singapore and Switzerland, consumption is lower:

While the USSR was known for bread lines, Americans are less burdened by the price of food than anyone in the world:

You didn’t see Americans risking life and limb to try to move to the Soviet Union in 1985. And yet in 2024 you do see tens of thousands of Chinese people risking life and limb to get into America for the chance of a better life. If the U.S. were the hellhole of despair that Ferguson’s post paints it as, you probably wouldn’t see that.

And in his headlong rush to declare national catastrophe, Ferguson also neglects to mention positive recent trends, such as the increase in life expectancy last year, youth suicide fell in 2022, and violent crime is falling fast.

A more balanced article, with fewer but stronger points, and more acknowledgement of America’s strengths, would have been more persuasive. The U.S. really does have many significant problems, including some of the ones Niall mentions (and a couple he doesn’t). We should try to focus on those problems instead of promoting an atmosphere of general despair, declinism, and panic.

2. Sorry, decels, but green energy is just going to win

Back in February I did a post with a bunch of handy charts about climate change. Here’s an update to that post, about green energy specifically.

The think tank RMI just released a big report about green energy. The report uses a couple of data presentation techniques I don’t like — most notably, drawing arrows on graphs to represent trend forecasts that aren’t based on data. But still, many of its charts are excellent and eye-opening.

Here’s a very cool chart showing solar costs relative to fossil fuels in electricity generation:

I especially like this chart because the distinction between “technologies” and “commodities” is a good one. Obviously technologies use commodities and commodities require technology to extract. But there’s a very important difference between stuff that we dig up out of the ground and stuff we assemble in a factory. And you can really see it on the chart. It took a long time, but human ingenuity is finally set to deliver us energy more abundant than what we got from coal and natural gas.

And as you’d expect given these cost declines, the amount of solar and batteries being used for generation around the world is skyrocketing:

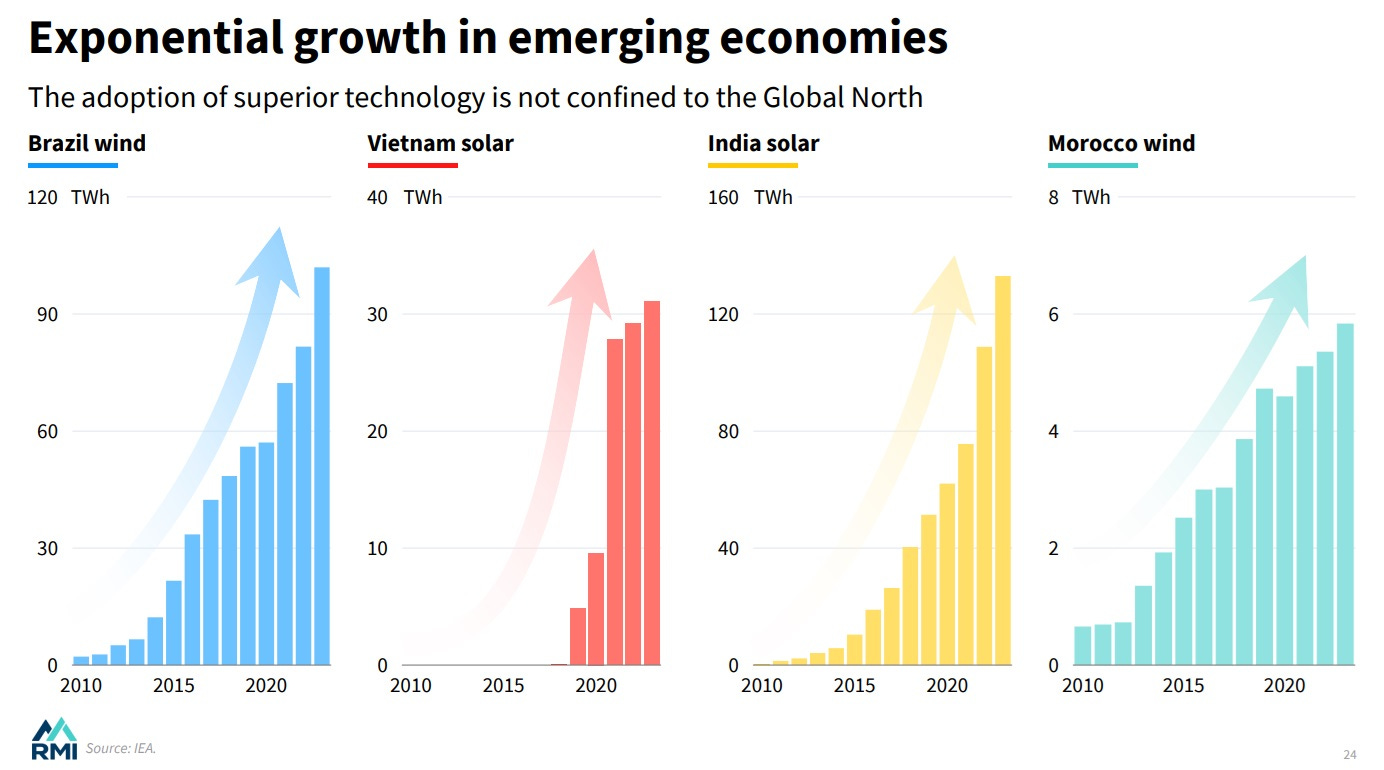

Whether this is fast enough to prevent catastrophic impacts from climate change is still an open question, of course. But encouragingly, major developing economies like India and Vietnam are hopping on this trend, suggesting that they will industrialize in a far less destructive way than Europe, America, and China did:

Developed countries are doing pretty well installing renewables as well. Here’s U.S. solar (switching to a different chart source just for a change of pace):

Interestingly, renewables aren’t leading to reliability problems, as many had predicted. Thanks to batteries, and to the complementarity of wind and solar, countries like Germany are getting more reliable electricity than before they added renewables:

Of course, China is the clear world leader in green energy. Everyone has seen charts of how much solar and batteries China is building, but it’s also incredible how fast they’re building an entire industrial economy that runs on electricity instead of combustion:

Anyway, there are plenty of other charts in the RMI report, even if they do have some data presentation issues, so check it out.

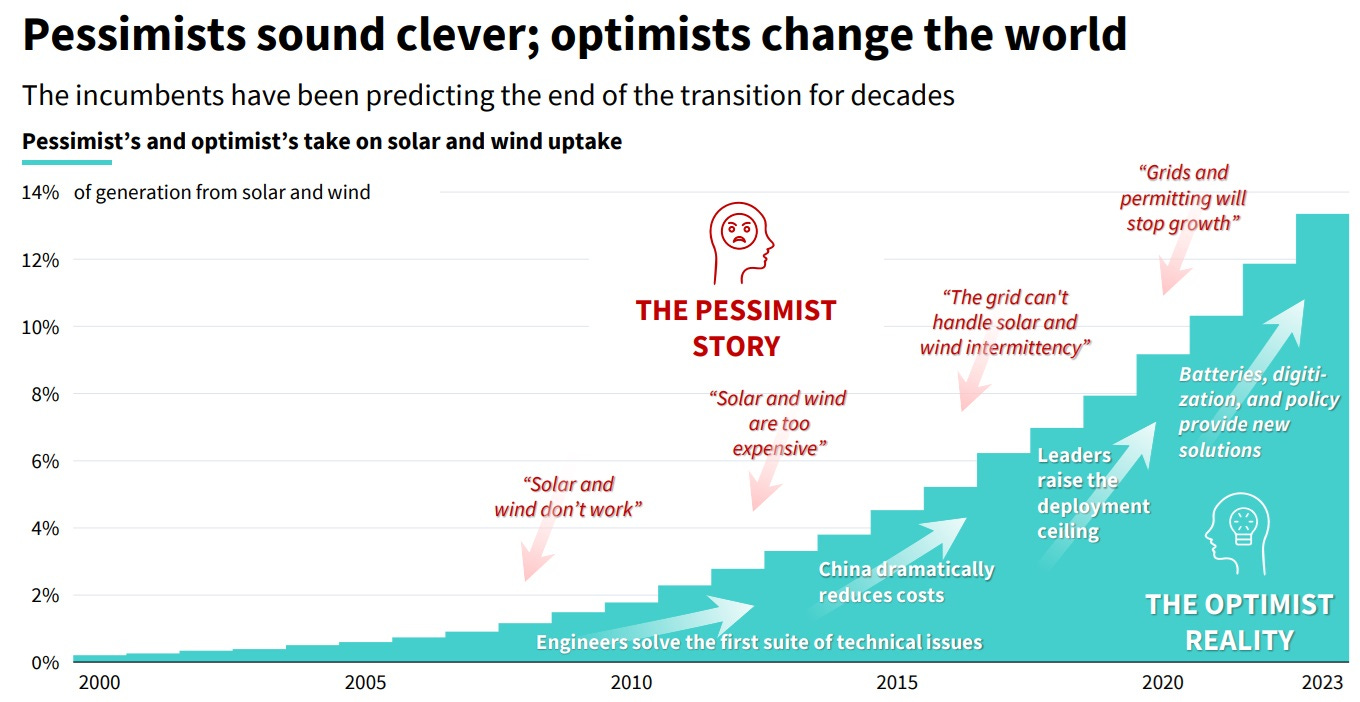

But I do want to share one more. This is really a combination of chart and meme, and thus it’s a little bit silly. But I think it shows pretty vividly how the renewable energy skeptics have been wrong again and again and again for years:

It just goes to show: Human ingenuity finds a way. Technology is the ultimate resource, and the decels who constantly predict that our energy problems would be too much for technology to handle have one of the worst prediction records of any group of intellectuals in modern history.

3. Trump’s tax cuts boosted investment a little bit

Hardcore Trump fans are always going to accuse me of having “Trump derangement syndrome”, but they’re wrong. I don’t like Trump, but I also acknowledge any number of good and useful things that Trump did.

Trump’s signature economic policies were 1) tariffs, and 2) tax reform (the TCJA). The main piece of tax reform was a big cut in the corporate tax rate, from 35% to 21%. People disappointed by the apparent failure of the Bush tax cuts in the 2000s were naturally skeptical, but in fact Trump’s policy had some economic theory on its side.

Classic econ theory predicts that corporate taxes are more harmful to the economy than personal income taxes; income taxes might make people work a little less today, but since corporate taxes reduce business investment, they lead to a less productive economy in the long term. Both of these effects are probably small, but the investment disincentive from corporate taxation compounds. So this theory — which might be wrong, just as all macroeconomic theories are pretty suspect — says that Trump was doing the right thing by cutting corporate taxes, and by raising personal income taxes a bit to partially offset the corporate tax cut.

Anyway, Trump’s tax cuts didn’t seem to have much of an effect in the year and a half after they were passed, and I was quick to declare the policy a disappointment. Too quick, as it turns out. With a few more years of data, Chodrow-Reich et al. (2024) have done some careful measurement that suggests Trump’s tax reform did in fact boost business investment by a substantial amount:

[T]he main domestic provisions—the reduction in the corporate rate and full expensing of investment—stimulated domestic investment substantially: firms with the mean tax change increased investment by 20% relative to firms experiencing no change.

To arrive at this number, the authors measure the relationship between how much of a tax break each company got, and that company’s reported capital expenditures. This requires a little bit of theory, because how much each company can expect its taxes to go down in the future is not entirely observable and requires some assumptions. But the assumptions are pretty basic and realistic. So this is probably as good a number as we’re going to get.

A 20% increase in corporate investment (for companies affected by the tax cuts) is a lot! And given America’s chronically low levels of capital expenditure, it’s a good thing. Now, that doesn’t translate into a 20% increase in the capital stock itself, thanks to depreciation and a bunch of other stuff. But Chowdrow-Reich et al. make a macro model (I know, I know) and find that this 20% boost in investment for certain companies translates to a 7% increase in the long-run U.S. capital stock. That’s a modest boost, but a real one.

So Trump’s tax cuts probably did help get American companies investing again, at least a little bit. Whether they were worth the costs in terms of higher federal budget deficits is another question entirely. The same model that Chodrow-Reich et al. use to predict a 7% increase in the capital stock also predicts that the TCJA will increase deficits substantially, with the higher revenue from increased economic activity offsetting only a very small percentage of the lost revenue from lower tax rates.

So people who learned the classic econ theory in school can breathe a sigh of relief — the world isn’t quite as topsy-turvy as we thought back in the late 2010s. Corporate tax cuts did work the way they were supposed to. But “supply-siders” who claim that tax cuts pay for themselves are still wrong. And the higher deficits from Trump’s tax cuts are now adding to the fiscal headache we’re facing in the era of higher interest rates.

4. The Build-Nothing Country: rural broadband, high-speed rail, and EV chargers

Last year, I wrote a post lamenting America’s seeming inability to build things:

I view this as America’s great generation challenge. Reversing the pro-stasis policies of the 1970s and once again becoming a nation of abundance will require any number of changes — permitting reform, a more effective bureaucracy, various kinds of deregulation, industrial policy, and renegotiations of the social compact between a wide variety of interest groups. This is not going to be quick or easy.

But just to maintain a sense of urgency, here are some updates on how bad things are.

Remember when we allocated tens of billions of government dollars to build rural broadband? Three years later, the broadband still does not exist:

Residents in rural America are eager to access high-speed internet under a $42.5 billion federal modernization program, but not a single home or business has been connected to new broadband networks nearly three years after President Biden signed the funding into law, and no project will break ground until sometime next year.

Lawmakers and internet companies blame the slow rollout on burdensome requirements for obtaining the funds, including climate change mandates, preferences for hiring union workers and the requirement that eligible companies prioritize the employment of “justice-impacted” people with criminal records to install broadband equipment.

The Commerce Department, which is distributing the funds under the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment (BEAD) program, is also attempting to regulate consumer rates, lawmakers say. This puts them at odds with internet providers and congressional Republicans, who say the law prohibits such regulation

We’re starting to get an idea of what holds up these projects. In this case it’s not NEPA or regulation — it’s a combination of onerous contracting requirements from the federal government, and political battles over implementation at the state level.

I’m not sure what to do about the political battles, but reducing the “everything bagel” of contracting requirements should be a major goal of the Republican alternative to Biden’s progressive industrial policy. Fortunately, some GOP legislators are now focusing on this.

And as Matt Yglesias writes, progressives really need to stop thinking of infrastructure and industrial policy chiefly in terms of the jobs these policies create, and start thinking about them in terms of the actual physical things they create.

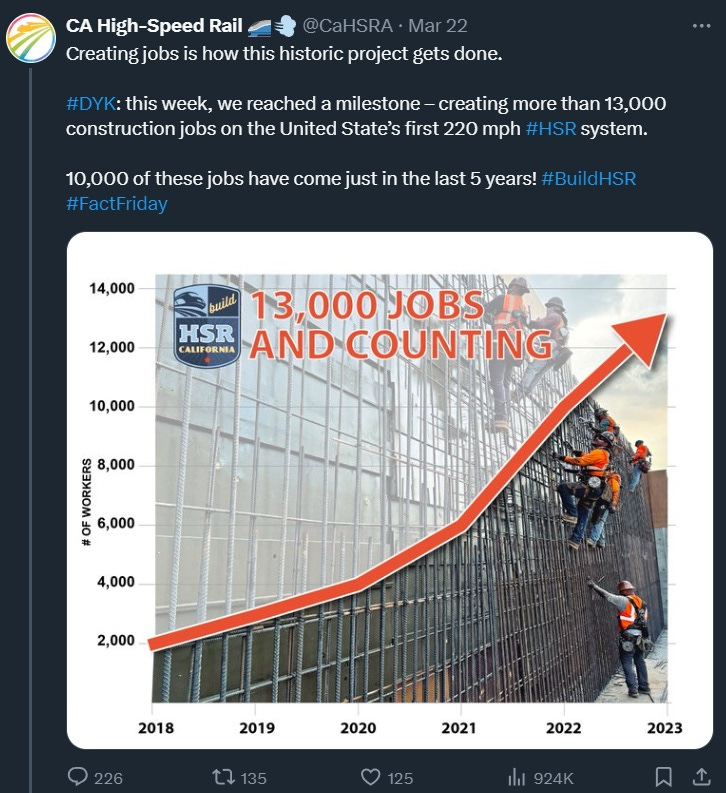

For example, California’s high-speed rail project was authorized well over a decade ago and has spent billions of dollars, but not one single mile of train is operational. And yet the California High Speed Rail Authority is bragging about how many jobs it created:

This tweet deservedly drew ridicule from across the political spectrum. Creating jobs but building nothing is not a victory; it is a failure. The purpose of infrastructure spending is to create infrastructure, not make-work. If progressives fail to understand that, Republicans will be able to ridicule government infrastructure spending as useless pork — and they won’t be wrong, either.

But anyway, another example of the Build-Nothing Country shows the multifaceted nature of the challenge we face. Remember the billions of dollars of federal money we allocated to building EV charging stations? Years later, only a tiny handful have actually been built:

President Biden has long vowed to build 500,000 electric vehicle charging stations in the United States by 2030…But now, more than two years after Congress allocated $7.5 billion to help build out those stations, only 7 EV charging stations are operational across four states…with a total of 38 spots where drivers can charge their vehicles…

Nick Nigro, founder of Atlas Public Policy, said that some of the delays are to be expected. “State transportation agencies are the recipients of the money,” he said. “Nearly all of them had no experience deploying electric vehicle charging stations before this law was enacted.”…Nigro says that the process — states have to submit plans to the Biden administration for approval, solicit bids on the work, and then award funds — has taken much of the first two years since the funding was approved…

Part of the slow rollout is that the new chargers are expected to be held to much higher standards than previous generations of fast chargers…But many non-Tesla fast chargers have a reputation for poor performance and sketchy reliability…EV policy experts say those requirements are critical to building a good nationwide charging program — but also slow down the build-out of the chargers.

Here we see a very different set of problems cropping up. Bureaucratic inadequacy — the fact that America’s civil service just doesn’t have the technical expertise or the personnel required to deal with this sudden new task — is cited as the main culprit. We also see the effects of the erosion of Western manufacturing, with companies other than Tesla unable to get the job done.

Unlike in the case of rural broadband, these are problems that progressives are better-equipped to solve than conservatives. Republicans are not going to beef up the civil service, and are more likely than Democrats to balk at industrial policy to restore U.S. manufacturing. And yet building good infrastructure will require both of those things.

So if we’re going to stop being the Build-Nothing Country, we need a combination of progressive and conservative approaches. Which means we need more compromises and less stonewalling. In the end, everything comes back to political cooperation.

5. Macro data mysteries: Indian manufacturing and EU growth

A couple of weeks ago I wrote a post about how bad data can cause us to get important facts about our economy wrong for a very long time, and even change the whole course of policy. In that post I said some nice things about economists, noting examples where reasoned debate and objectivity mostly prevailed over sensationalism and partisanship. But that doesn’t mean economic data is always solid or reliable! In fact, in recent days I’ve noticed a couple of examples of macroeconomic data mysteries that could have very big implications.

The first concerns India’s manufacturing sector. Conventional wisdom holds that India is a service industry superpower but a manufacturing minnow. In fact, World Bank data shows Indian manufacturing plummeting as a share of GDP in recent years:

And yet when you look at employment in India, manufacturing dominates services:

Now, these two things aren’t necessarily contradictory — services could just be much much more productive than manufacturing in India — but it’s certainly a disparity that needs explaining. So I was very interested when I noticed that there’s actually a big debate in India about how the manufacturing industry is measured. This is from 2017:

A unending debate on the gross domestic product (GDP) growth numbers brought out by the Central Statistics Office (CSO) has been doing the rounds…There are two methodologies for deflating the current price GVA (gross value added) numbers to their constant price equivalents: single deflation and double deflation. While the single deflation method argues for one-time series proxy deflator for both input and output at the current price, the double deflation method involves using a different deflator for output and input, for obtaining values of output and GVA at constant prices…

The CSO has been using a mix of the two methods. For sectors other than agriculture, and mining and quarrying, it has been using the single deflation method. This approach is debatable since the eight key components of GVA and their sub-components are not treated in a similar fashion, preventing the comparison of progress across sectors.

With this adjustment, Jyoti Sharma finds that Indian manufacturing grew almost three times as fast in 2015-16 as official numbers suggest, and services grew much more slowly. This leads some Indian pundits to argue that recent Indian growth has actually been manufacturing-led rather than services-led.

This is an incredibly important question! Some people argue that India should lean into its strengths and focus more on service sectors, while others say that India should focus on shoring up its weakness in manufacturing. But if India has actually been doing a lot more manufacturing than anyone realizes, and that this has been covered up by a statistical quirk that measures prices differently for services than for manufacturing, then all of these big momentous debates need to change.

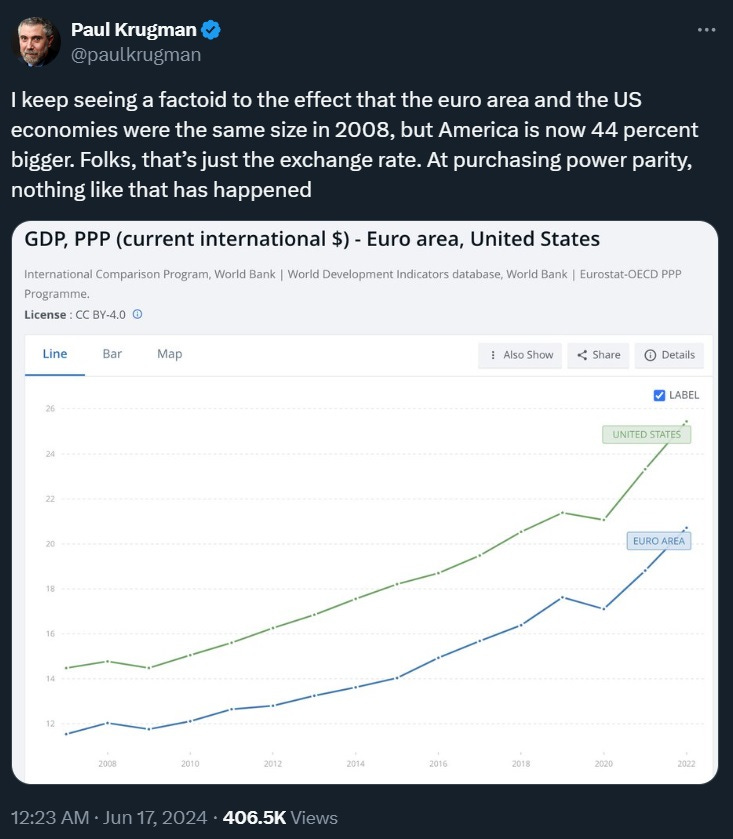

The second data mystery concerns the growth gap between the EU and the U.S. This chart has been making the rounds, showing a huge divergence between eurozone and U.S. productivity growth rates since the 2008 financial crisis:

Paul Krugman claimed that this is just a statistical illusion, caused by the weakening of the euro relative to the U.S. dollar since 2008:

But the way the FT chart is constructed, you shouldn’t need to apply a PPP adjustment. If you start both U.S. and eurozone GDP at 100, you can just use each zone’s own prices to calculate real growth over time. So the growth lines in the Financial Times graph should already reflect price differences between the two zones — in other words, they are, in principle, already adjusted for PPP.

So why the big divergence? Thomas Philippon realized that the U.S. and eurozone inflation numbers are wildly different than the price numbers calculated by the World Bank people who calculate PPP. Two different sets of researchers are finding very different price numbers — the eurozone people think their prices have gone up a lot more than the World Bank people think.

And it’s just not clear yet who’s right. People are looking into the difference, but for now we just don’t know whether Europe has been mostly keeping pace with the U.S. or falling behind.

How’s that for epistemic uncertainty?

Anyway, when I find the answer to these mysteries, I will let you know. In the meantime, the big takeaway here is that countries have to make world-altering decisions based on data that occasionally have huge problems. Such is the nature of our uncertain world. The only thing we can do is to look at as many different high-quality, carefully researched data sources as we can, and try to figure out the causes of any disagreements.

Ferguson is a hack. When he fails to deal with the mendacity of Conservatism, the criminality for the sport of it by Roger Stone et al, and Trump’s pardoning of Stone, Manafort, et al (while letting the snowflake tears pour from his eyes about a jury finding Trump guilty thirty-four times) it’s a waste of time taking him seriously. Corruption? Not a mention of the Republican appointment dominated US Supreme Court, which is a cabal of men, a cowed woman, who proclaim themselves above the law. Ferguson can keep pretending his accent gives him weight, but a hack is a hack is a hack.

Ferguson's article is much worse than you let on.

He never does a direct US-China comparison on any metric. Wherever he does compare USSR and USA, he notes that USA's numbers are much better, but worse than expected(no mention of China).

There's almost no attempt to prove Chinese superiority on any of the criticisms he makes.

He never tries to show any similarity between 80s USA and modern China.

Everything he says about foreign policy is built on false premises.

Even if one agrees with the title, that was a terrible article.