At least five interesting things to start your week (#28)

Cultural stagnation, pedestrian deaths, evidence on decoupling, the benefits of education, and why philosophers read the classics

Hey, folks! Hope you’re having a great Presidents’ Day weekend — or if you don’t live in the U.S., just a great regular weekend. I’ve got a few podcasts for you today. First, Erik Torenberg and I talk about tariffs on Econ 102:

And we also have another episode out where we talk about economic development:

You can also listen to these on Apple Podcasts or watch them on YouTube.

Brad DeLong and I also have another episode of Hexapodia, in which we discuss the Vibecession:

Anyway, on to the list of interesting things! I had initially planned to put eight things here, but it was getting really long, so I decided to save a few for the next roundup.

1. Pop culture has begun to stagnate

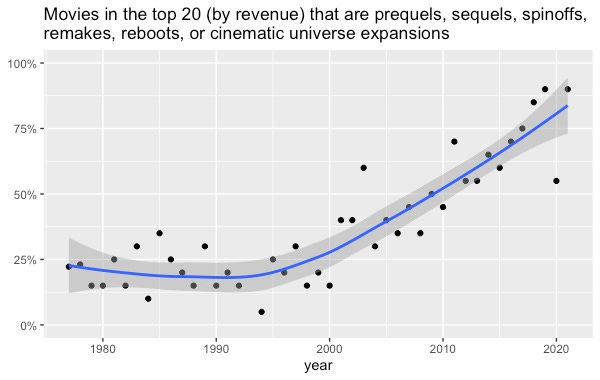

I missed this important blog post by Adam Mastroianni back in 2022 (fortunately, Ethan Mollick brought it to my attention). The post is about how pop culture — movies, books, music, TV, and so on — has been recycling more and more of its material in recent decades. Here are a few of Mastroianni’s charts:

I think this is an interesting qualifier to the common belief that entertainment culture is becoming more fragmented. Yes, the internet has led to a massive long tail of indie content. But at the same time, the number of top movie and TV franchises, authors, and musical artists has shrunk. Maybe it’s more accurate to say that the distribution of taste has become more fat-tailed — narrower in the center but with more of the mass at the fringes. Consistent with this, Mastroianni points out that indie content is still going strong.

Anyway, we don’t really know why this is happening, and Mastroianni offers various theories. But I think we should pay attention to the timing differences in his graphs. The “sequels and remakes” trend in movies starts around the mid-90s. The dominance of top authors begins around the same time. But the concentration of top musical artists and the proliferation of TV spinoffs happen mostly in the 1970s and 1980s.

To me, this suggests that we’re looking at a story about distribution technology. Cable TV became popular in the 70s and 80s, as did physical sales of recorded music on vinyl and cassette tape. The 90s and 00s saw an explosion of high-quality recorded movies on DVD, as well as the rise of big chain bookstores and Amazon.

In other words, my bet is that when an entertainment medium gets easier to distribute, we tend to see two parallel trends: a proliferation of niche indie media, and a reduction in the number of big hits. And my hypothesis is that this has to do with the three reasons people enjoy consuming media: 1) to enjoy things for their own sake, 2) to share experience of the media among a small group of friends or fellow superfans, and 3) to be in touch with the rest of the populace by consuming the same things they do. You could call these “pure consumption”, “fandom”, and “mass culture”.

Easier distribution makes (1) and (3) easier. There are far more things to enjoy for their own sake. And it’s easier for society as a whole to coordinate on a few things that everyone knows and recognizes. But it might make (2) harder, because fandoms are coordination problems — the more content there is, the harder it is for small groups to decide which things to coordinate on.

2. Why are more pedestrians dying in the U.S.? It’s not because of heavier cars.

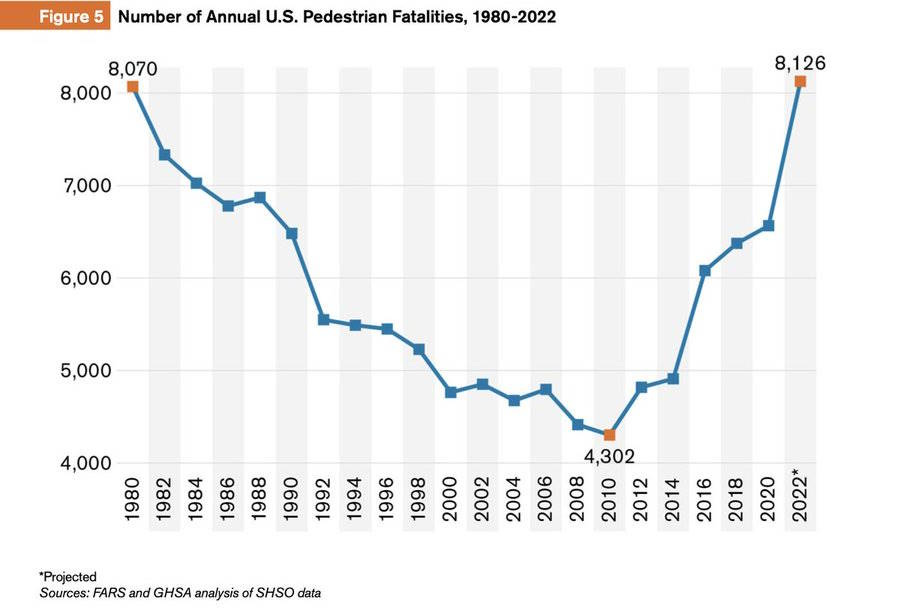

Since 2010, American roads have been getting more and more dangerous for pedestrians:

Urbanists love to blame this trend on the rise of bigger, heavier, cars. But they’re just wrong. First of all, the physics doesn’t make a lot of sense — even a “small”, “light” car is so much heavier than a human being that the mass difference may as well be infinite, meaning that making cars even heavier won’t increase the amount of energy or momentum they transfer to a pedestrian in a collision. (A lot of people very confidently get this wrong.) It’s also inconsistent with the evidence — all of the increase in U.S. vehicle weight happened between the late 80s and the mid-2000s. During that entire time, pedestrian fatalities were falling. Pedestrian deaths only rose after 2010, after vehicle weights had stopped rising.

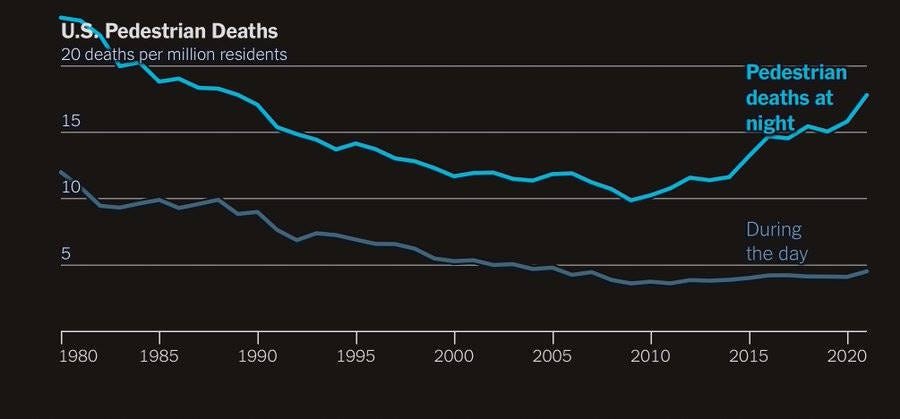

There is slightly increased danger of fatality from taller cars, since these cars tend to strike pedestrians in the head and chest rather than in the legs and hips. But in practice, this doesn’t look like a big deal. A New York Times article notes that pedestrian deaths during the day haven’t risen; all the increase is coming from deaths at night:

Presumably if cars are getting larger and more dangerous, they are larger during the day as well as during the night. So this evidence is inconsistent with the “bigger cars” explanation. Another data point is that kids and old people are actually being hit less:

Presumably bigger cars are also more dangerous to kids and old people, yet kids and old people are dying less.

So what’s causing the increase in daytime pedestrian deaths of adults aged 18-64? The NYT writers suggest that smartphones are to blame. But as much as I love to blame bad stuff on phones, I’m not quite convinced yet. First of all, other rich countries have phones, and their roads have been getting safer. Maybe it’s because Europeans are more likely to use manual transmissions, preventing them from using their phones in the car. But phone use is pretty constant throughout the day, while pedestrian deaths spike abruptly in the evening.

So I’m willing to believe the phones explanation, especially since the timing works out perfectly on a macro level. But I think we need more evidence, including cross-country studies on time spent using phones while driving in various countries. In any case, bigger, heavier cars don’t look like the culprit here.

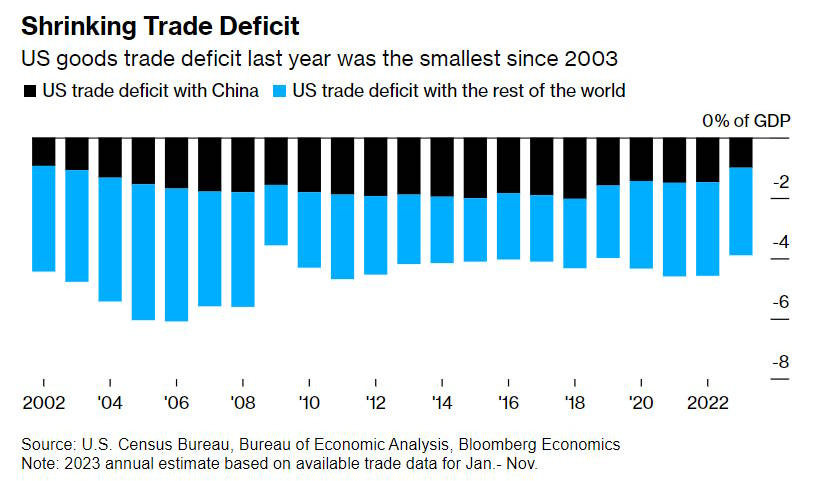

3. An illustration of why the “decoupling is fake” story is overdone

Bloomberg reports that the U.S. trade deficit with China has shrunk again:

But the reports allege that this isn’t real decoupling, since Chinese goods are simply “making a pit stop” in places like Mexico and Vietnam before being shipped on to the U.S.:

There’s a new reason why the goods trade deficit with China is an imperfect metric: Shipments from the Asian manufacturing powerhouse to the US are increasingly making a pit stop in third countries such as Vietnam and Mexico…China’s declining role in the final assembly of many products and the shift elsewhere means other countries now claim the total export value of finished goods like mobile phones, even if much of the added value comes from other places in the supply chain including China.

But as I wrote in a pair of posts last year, this doesn’t mean that U.S.-China decoupling is fake. Macro numbers alone don’t tell you how much of the value of what the U.S. consumes is actually made in China. Chinese exports of materials, parts and components to Mexico and Vietnam are obviously some part of the story here, but just how much of the story we don’t know yet (since it takes several years to compile data on value-added trade).

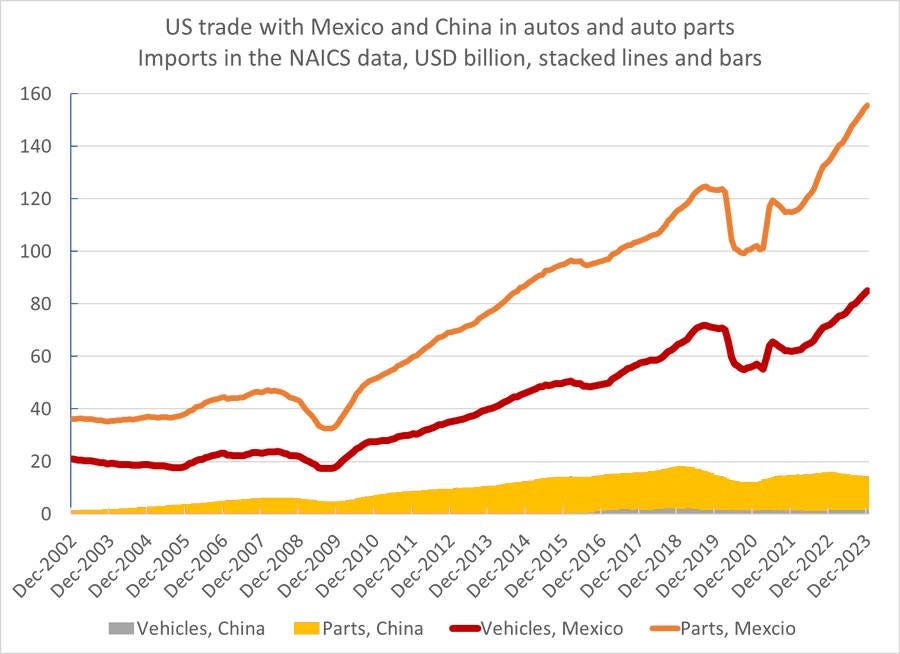

In fact we do have a bit of data on trade in intermediate goods. And the data we have often runs counter to the story that Mexican and Vietnamese exports to the U.S. are just wrappers on Chinese exports. For example, Brad Setser recently took a look at Mexican vs. Chinese exports of autos and auto parts to the U.S.:

What this shows is that the U.S. never bought many cars or car parts from China in the first place. And it also shows that Mexico isn’t just exporting a bunch of finished autos to the U.S. — it’s exporting a bunch of auto parts too. In fact, Mexico’s parts exports have grown even more than its car exports.

This shows that America’s rising car imports from Mexico aren’t a story about Mexico assembling Chinese-made car parts. Mexico is making the parts themselves. That doesn’t mean China is totally out of the supply chain — some of the raw material that goes into making the Mexican auto parts might come from China, which does a lot of the world’s metal processing. But making auto parts and assembling of finished cars represent most of the value in the auto manufacturing process.

Now note that at the same time Mexico is selling more cars and car parts to the U.S., China is selling more cars to Mexico. The point here is that these aren’t the same cars! Mexico is buying more Chinese cars, and quite separately, it’s making and selling more American cars and car parts. If you only looked at car imports and exports, without looking at parts, you’d miss this.

This isn’t a major source of decoupling, since the U.S. never bought many cars or parts from China in the first place. But it shows why macro numbers like bilateral trade deficits don’t tell us how much decoupling is or isn’t happening. We have to wait for the more detailed numbers to come out.

4. An unconvincing argument against the usefulness of additional education

Gregory Clark and Christian Nielsen have a new paper claiming that education is — at least on the margin — pretty useless. But I’m not buying it.

There are a bunch of empirical econ papers finding positive effects from making kids get more education. This is usually expressed as a “rate of return”, which in this literature means how much more money the kids end up making when they grow up. In recent years, economists have focused on making sure that the estimates they get are causal, not just correlation. They do this by looking for policy changes that randomly affected some kids more than others, forcing some of the kids to stay in school for a bit longer. By comparing the two groups of students, economists basically have a randomized trial; this is called a natural experiment.

These natural experiments usually find positive effects of education — the average return on investment is around 8.5% for one more year of schooling. But Clark and Nielsen, looking at 66 of these papers, argue that there’s substantial publication bias at work — they argue that there are a bunch of papers finding negative effects of education that aren’t getting published.

How do they arrive at this conclusion? First, they do a standard test for publication bias — they look for a correlation between effect size and standard error. If the crappier studies tend to be the ones finding bigger effects, that’s a big red flag. But Clark and Nielson find no correlation. So this classic sign of publication bias isn’t present.

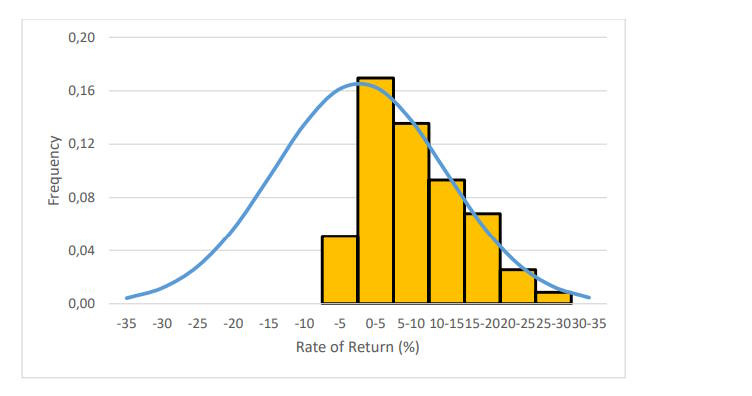

But then they plot a histogram of the returns found in the papers, and find that it doesn’t look like a normal distribution:

They conclude that there are a bunch of very negative estimates that are being left unpublished. Since the peak of the normal distribution they draw (the blue curve on the graph) is around 0, they conclude that the true effect of education, on the margin, is basically nil.

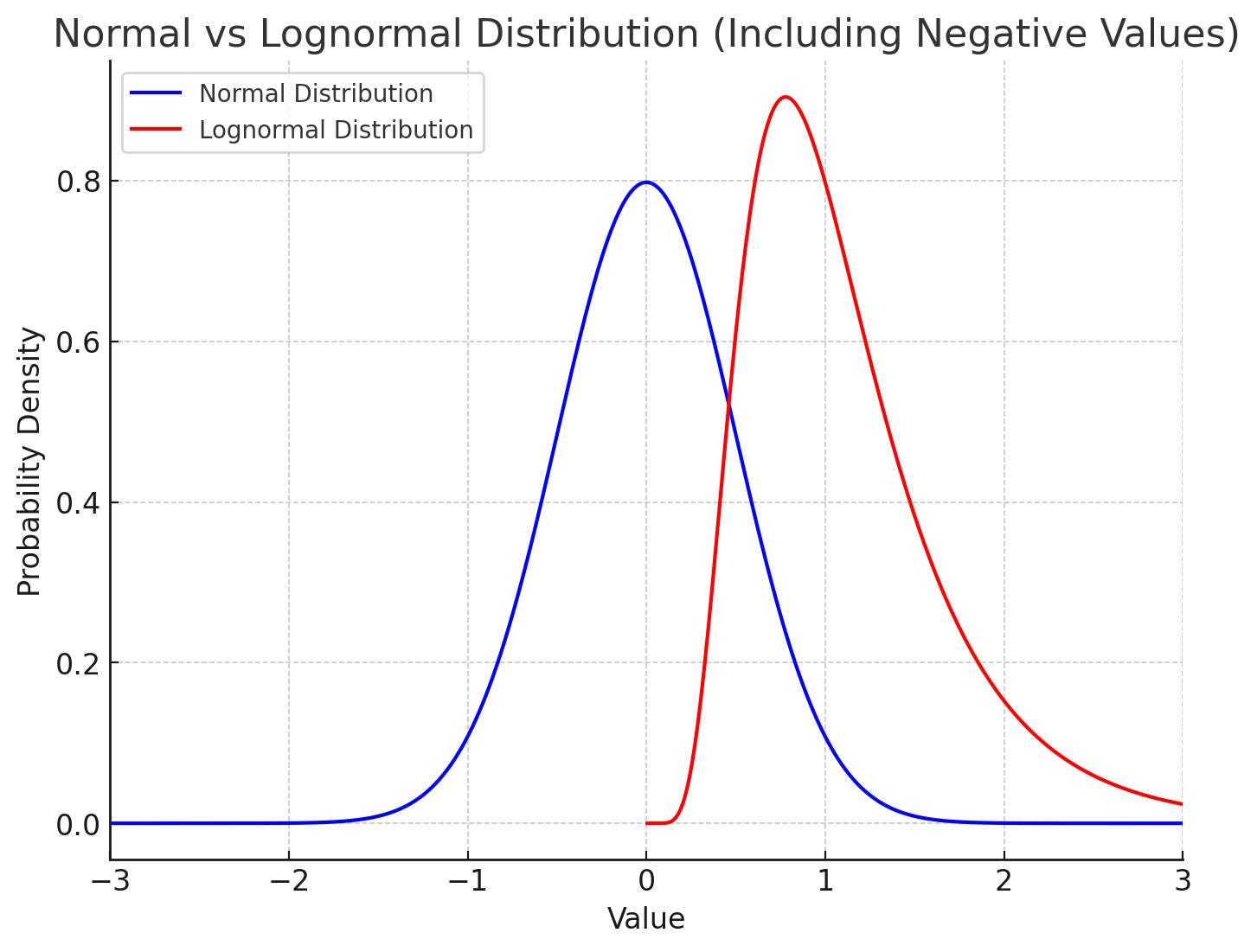

But Rachel Meager argues that this is not a good method. She argues that the returns to schooling should be plotted in logs. If the random errors in economists’ estimates of the log return to education are normally distributed, the returns themselves will follow a log-normal distribution. That looks like this:

Note that the red distribution here — the lognormal — looks pretty close to the yellow histogram in Clark and Nielsen’s graph.

When do you use log returns? When there’s some lower bound on your returns. It’s incredibly unlikely that any researcher would ever find that an additional year of education causes kids to make 25% less money when they grow up. At worst, schooling is probably just a waste of time; it’s highly unlikely that it makes you less successful in life. So that’s the argument for using a lognormal distribution. And if you use a lognormal, just eyeballing that yellow histogram, it doesn’t look like there’s going to be publication bias here.

Thus, I don’t find Clark and Nielsen’s meta-analysis to be very persuasive here.

5. Should philosophers have to study the classics?

Singaporean college student Pradyumna Prasad recently asked an interesting question: If science students don’t read the classics, why should philosophy students read the classics?

This question prompted the usual chorus of disdain from people in the humanities (and from people who think that defending the humanities against attacks from STEMlords is an important political battle). But it’s a valid and interesting question. No, most physics students don’t go back and read Newton or Maxwell or Faraday or Kelvin, or even Einstein. But most philosophy students will read at least a few of the old classic thinkers, and often quite a lot. Why the difference?

My view is that the difference comes from summarizability. Newton’s laws of motion can be fully and easily understood without reading Newton — as can every other piece of physics that Newton ever invented. So unless you’re studying the history of thought, there’s no real reason to wade through Newton’s antiquated language, incomplete thinking, and roundabout discovery process. If you just want the physics itself, read a textbook, and you’ll get it.

Most philosophy, on the other hand, is hard to summarize. There are exceptions (e.g. logic), but the thought of Plato or Hume or Hegel can’t be easily summarized in a far shorter form without losing some of the nuance and depth of the original. Or more precisely, even if it can be summarized, the accuracy of that summary is difficult to verify — some grad student might actually be able to tell you all you really need to know about Plato, but how would you know that? In contrast, you can know you got a good summary of Newton because the summarized physics demonstrably works.

And that, I think, gets to the real crux of the difference: We expect different things from physicists and philosophers. We mainly expect physicists to produce functional devices and well-evidenced theoretical insights that are easy to communicate, learn, and apply. We expect philosophers to help us think about complex problems that usually have no definitive, verifiably “correct” answer. The former requires simplicity, the latter requires nuance and depth.

It also shows that there’s more than one meaning of the word “progress”. In physics, with its focus on simplicity and applicability, progress means subsuming or replacing old theories and improving on old technologies. In philosophy, progress often means adding a perspective on an old question, without necessarily discarding the old perspectives.

That doesn’t mean that progress in philosophy is incapable of stalling out, of course. Liam Bright, a philosopher at the London School of Economics, argues that analytic philosophy has largely stopped generating useful new insights. I have no idea if he’s right or wrong. My point is simply that progress in philosophy can be more like adding new tools to a collection, instead of replacing obsolete tools with better ones.

It's quite obvious that the increased pedestrian fatalities come form increased homelessness, drug use and where homeless people live (often around highways). Even that quoted NYT article says "In 2021, 70 percent of Portland’s pedestrian fatalities were among the homeless." This seems like a big omission in Mr. Smith's argument.

I've got a hunch that cultural stagnation has at least something to do with a fear of transgressing boundaries. Killing sacred cows and challenging the prevailing wisdom used to be at the forefront of culture and it's not anymore. There's a deep fear of cancel culture, so people in our cultural spaces tend to play it safe these days - at least in comparison to the 70s and 80s. Additionally, the cultural gatekeepers have themselves become highly intolerant, far less willing than they used to be to quickly champion rule breakers. Think of the Lower East Side Movement of the early 1980s - people went to jail for showing the work of Robert Mapplethorpe, a gay artist whose deeply beautiful photographs of flowers, objects and naked men were deeply controversial at the time. But museums and gallery owners risked showing his work. Today? Not sure they would.