At least five interesting things: It Isn't That Bad edition (#66)

U.S. wage growth; fertility and sexism; construction costs and house prices; the next financial crisis; macroeconomics vs. microeconomics;

Wow, I just realized it’s been a long time since I did a roundup! I hope I haven’t gotten rusty.

First, podcasts. I went on the Big Technology podcast to talk about AI taking jobs, and why humanity could end up being just fine no matter how good AI gets:

A few weeks ago, I went on the WhoWhatWhy podcast with Jeff Schechtman, to discuss the economy:

And finally, here’s an episode of Econ 102, in which Erik and I talk about the revolution China is creating in physical technologies:

Anyway, on to the list of interesting things!

1. American wages really have gone up

For years, we’ve been deluged with charts and rhetoric and memes about how American wages haven’t gone up for decades. Bernie Sanders, for instance, regularly claims that wages are lower than they were 50 years ago. Is it true, though?

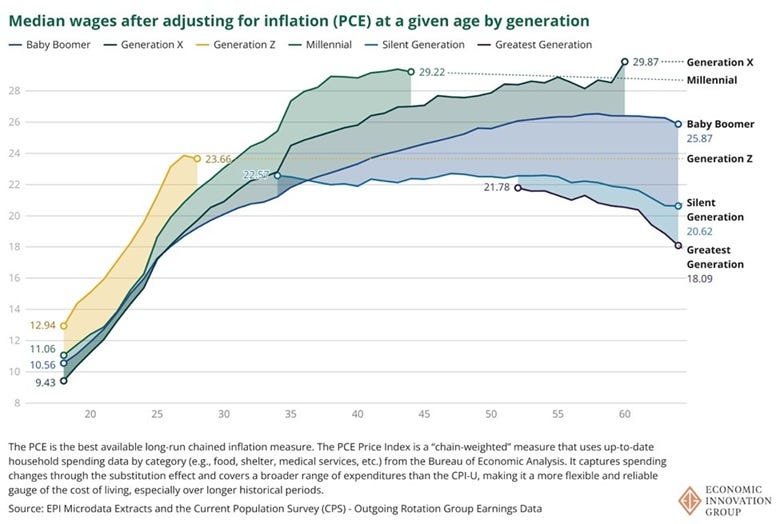

No. The basis for this claim is one particular data set: average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers in the private sector, divided by the consumer price index. That measure of wages was indeed lower in 2019 than in 1973. But if you use the PCE price index instead — which measures the changes in the prices of what people actually consume, rather than what they used to consume in the past — you see a very different story:

This is enough to show that the U.S. economy as a whole is delivering wage growth (though less than we’d like, of course). But what we really care about on a personal level, when it comes to wage trends, is probably some combination of two questions:

How much do a typical person’s wages increase over time?

Do young people make more than their parents did at a similar age?

Ben Glasner of the Economic Innovation Group has a great chart that allows us to see the answer to those two questions in a nutshell:

We can see that every American generation’s income, except for the Silent Generation, has risen strongly over the first two decades of their working life. We can also see that Gen Xers started earning more than the Boomers after about age 27, and that Millennials started earning more than the Xers around age 25. Those generation gaps widened over time, as the younger generations pulled away from the older ones.

Most importantly, we can see that Zoomers — the current young generation — beat the wages of the Millennials, Xers, or Boomers right out of the gate. Gen Z has benefitted from a strong re-acceleration of American wage growth since the early 2010s.

If people tell you that the American economy is not delivering higher wages over time, they’re just wrong.

2. Is sexism the key to high fertility?

The public discussion around birth rates is incredibly cursed. Aging and shrinking populations are a huge long-term economic problem that nobody has yet figured out how to solve. And yet debates about the problem almost instantly degenerate into racism, sexism, and accusations of racism and sexism. Thus, as a society, we’re not yet able to take this looming threat seriously.

One reason for this is the correlation between women’s education and fertility. If you look at a chart, you see that there are no high-fertility countries where the average woman completes high school:

To rightists, this correlation suggests not just a causal effect, but an ironclad law — if you want to preserve the human race, you must prevent girls from going to school. Thus, they believe that the only societies that survive will be sexist ones that treat women as breeding machines instead of economic providers. Naturally, this idea makes a lot of people very mad.

But is it true? Everyone knows how to mouth the phrase “correlation isn’t causation”, but when the rubber hits the road, do they really understand what that means? Just observing that women’s education and fertility are negatively correlated doesn’t tell you whether preventing women from going to school would make people have a bunch of kids.

Maybe the countries with low female education and high fertility are just deeply economically dysfunctional. Maybe this prevents governments from rolling out good education systems, and keeps young girls working out of economic necessity. And maybe this dysfunction also means that more kids are needed to work the fields, or that kids represent the only way people can economically survive in old age — thus raising birth rates. If this is true, then taking girls out of school won’t restore high fertility unless you also return your country to a pre-industrial standard of living.

In fact, there is some research about the causality here (which few of the people in the public debate seem interested in referencing or even reading). Some studies in poor African countries find that sending girls to school for an additional year does reduce childbearing. And that effect probably would be big enough to explain the observed fertility drop from 0 to 8 years of schooling.

But this estimate might not actually hold for higher levels of schooling; it doesn’t really tell us what happens when you go from, say, 9 to 14 years of female education. Chen (2022) looked at an expansion of higher education in China, and found that it actually raised birth rates by a significant amount. Monstad et al. (2008) found zero effect of education on fertility in Norway, and Cummins (2025) find zero effect in England.

So it may be that while giving girls an education reduces fertility rates from the unsustainable, explosive level of 7-8 children per women to maybe 3 or 4, the “last mile” — the drop of fertility below the replacement rate — is due to something else entirely. And since we really do not want to fertility rates of 7-8, this would mean that sending girls to school is unambiguously good for population stability.

If we want to fix the fertility crisis, we should probably not try to transform our society into The Handmaid’s Tale.

3. Do construction costs really not matter that much for housing prices?

One of my favorite bloggers has teamed up with one of my favorite economists to write a paper about housing costs! It’s Christmas in July! Brian Potter, the author of the excellent blog Construction Physics, knows a whole lot about construction costs. And Chad Syverson of the University of Chicago is the undisputed master1 when it comes to measuring productivity. Together, they have written a paper entitled “Building Costs and House Prices”. They write:

Perhaps the clearest conclusion of our analysis is that building costs have never had all that much explanatory power over US housing prices, but even the imperfect correlations of the past have weakened further in recent decades along multiple dimensions.

This is an important result, but — surprisingly — I’m a little unhappy about how the authors frame this conclusion. When you read a sentence like “building costs have never had all that much explanatory power over U.S. housing prices”, you might conclude that we shouldn’t worry about whether it costs $1 million to build a single small unit of affordable housing in San Francisco. And this might imply that we shouldn’t worry about policies that increase housing construction costs, such as onerous contracting requirements or construction regulations. It might also imply that we shouldn’t worry about the stagnation in construction productivity (which Brian Potter has written extensively on).

In fact, this is not what Potter and Syverson are trying to tell us. What they actually mean when they say that construction costs have little “explanatory power” over house prices is three things:

House price differences between cities aren’t very correlated with construction cost differences.

Differences in the rate of growth of house prices between cities aren’t very correlated with differences in the rate of growth of construction costs.

Changes in the rate of growth of U.S. house prices over time don’t seem to line up with changes in the rate of growth of construction costs.

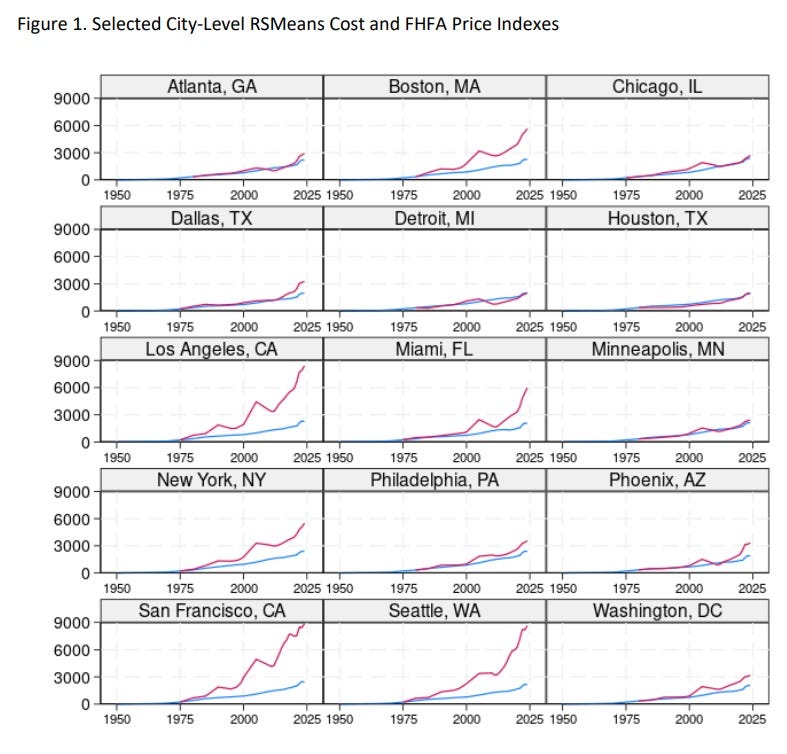

You can really see these conclusions from looking at a single, excellent chart that Potter and Syverson make:

You can see that for some cities like Minneapolis, Houston, Detroit, and Atlanta, prices (the red line) and costs (the blue line) line up almost exactly. But for other cities, like San Francisco, Seattle, Los Angeles, and NYC, prices soar far above costs. These are the “superstar” cities, where people are paying a huge and growing premium to buy houses.

That difference between superstar cities and “normal” cities can explain Potter and Syverson’s findings. Since construction costs alone don’t tell you whether your city is a superstar, just looking at costs can’t predict whether prices in your city will grow like crazy or stay in line with costs. And the emergence of superstar cities as a new phenomenon over time means that the relationship between costs and prices in the country overall has broken down.

And yet if you live in Minneapolis, Houston, Detroit, or Atlanta, you probably do care a lot about construction costs. Sure, higher costs won’t turn you into San Francisco. But they probably will drive up prices. Just from basic theory, or from looking at Potter and Syverson’s chart, it’s pretty hard to argue that raising the cost of building a home in Minneapolis to $10 million with boneheaded regulations wouldn’t make housing a lot less affordable for the people of Minneapolis.

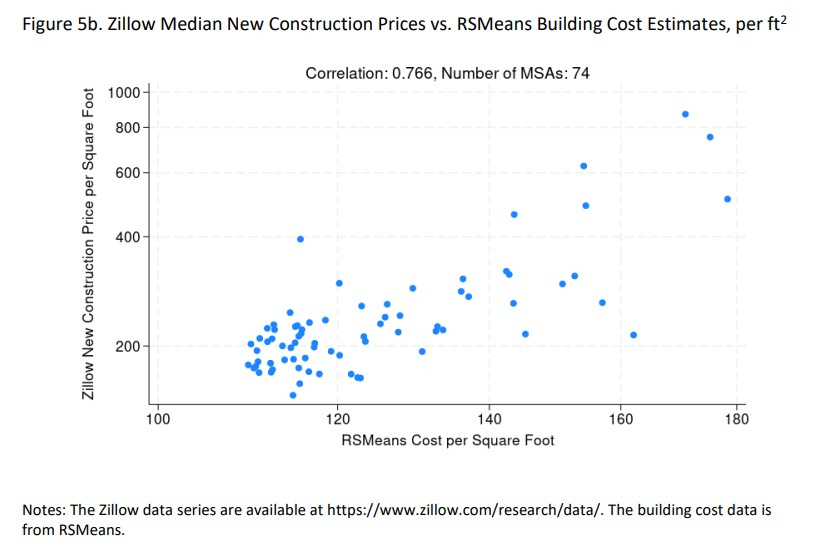

Also, the construction cost data that Potter and Syverson use is cost per house, rather than cost per square foot. When they use cost per square foot, it turns out that construction costs are a lot more correlated with housing prices than in their baseline results:

As one further check on the housing cost-price relationship, we note our [construction] cost levels for every city are for a house with standardized attributes, including size. If the size of median homes differs systematically across cities, this could be another reason for a wedge between prices and building costs. To check this, we compare both Zillow prices (though just for new construction) and RSMeans cost estimates in terms of dollars per square foot for 74 of the 100 cities in our original sample. The regression coefficient of prices on costs using this per unit-area data is 2.16 (s.e. = 0.33), with an R2 of 0.59…Adjusting for the fact that RSMeans cost estimates focus on new construction and for differences in house sizes across metros substantially raises they ability of building costs to explain house prices…That said, even in this best case, almost half of the variation in housing prices remains unexplained.

Um…an R-squared of 0.59 is really high, as empirical results go. And the chart looks like a solid correlation:

I’m not quite sure why the authors decided not to make this substantial correlation the baseline result.

Yes, there are clearly other important factors explaining housing prices — supply restrictions and price bubbles probably being the two main ones. Yes, costs don’t explain the “superstar city” effect that has driven prices off the charts in a few coastal metros. But at the end of the day, this paper still gives me reason to be concerned about stagnating construction productivity.

4. Where will the next financial crisis come from?

After the financial crisis of 2008, a common parlor game was to guess where the next financial crisis was going to come from. It never came — at least, not so far. This is probably at least partly an observer effect — because everyone was thinking about financial crises, they were paying a lot of attention to risks of all kinds, which prevented the systemic risk-buildup that causes a crisis.

But now it’s been a long time, so maybe people are getting complacent enough that the seeds of another financial crisis could start to grow. In general, the risks that lead to a financial crisis tend to be concentrated in some hot, new, poorly understood sector of the economy — railroads in the 1870s, financial engineering in the 2000s, and so on. Today, the two obvious hot new poorly understood sectors would be crypto and AI.

And when we look for potential financial crises, we want to look at buildups of debt. It’s debt defaults, not declines in equity prices, that put financial institutions in danger of insolvency. Leverage magnifies risk, and chains of lending increase the complexity and the fragility of the system.

Crypto, being basically just a form of poorly regulated finance, seems almost designed to produce financial crises. For a long time, crypto basically didn’t involve any debt, so when it crashed, people lost their money but nothing systemic went down.2 But I start to get a little worried when I see stories like this one in USA Today:

Due to the rising cost of housing in America, many young people now think they might not ever be able to afford a new house. But don't worry, Bitcoin…could change all that and make home ownership a reality…At the end of June, the U.S. Federal Housing Finance Agency issued a new directive, instructing both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to count Bitcoin as an asset on single-family home mortgage applications. Previously, mortgage applicants had to convert any Bitcoin holdings into U.S. dollars if they wanted their crypto to count.

Given Bitcoin's rapid price appreciation over the past decade, this move could end up being a real game-changer…[I]nvesting in Bitcoin could help you afford your next house. Bitcoin is a disinflationary asset and a potential hedge against inflation. Best of all, Bitcoin is widely available to everyone…The really exciting part about all this is that many top investors now expect Bitcoin to hit $1 million within the next five years. For example, Cathie Wood of Ark Invest thinks Bitcoin will hit $1.48 million by the year 2030…Given Bitcoin's current price of $107,000, that's a more than 10x increase within a very short period of time. With those types of gains, you could be well on your way to home ownership in just a few years.

If you grimaced while you read that, you weren’t alone. What if a bunch of unqualified borrowers get mortgages because the government sees that they have a lot of Bitcoin, and assumes that they can pay off their mortgages with the price appreciation of Bitcoin? And then what if Bitcoin goes down in price a bunch, and people start defaulting on their mortgages en masse? The sort of glowing, breathless, “prices can never go down” prose of that article I just quoted from will sound familiar to everyone who lived through the early 2000s.

It’s also possible that the next financial crisis might come from AI — specifically, from the enormous debt-financed boom in data centers. Paul Kedrosky has a great post warning that the companies building these giant data centers are trying to hide their debt:

I was struck late this past week by Meta's rumored $29b fundraising for a rapid buildout of more AI data centers. The company is supposedly talking to various private equity firms, looking to structure it as $26 billion in debt, $3 billion in equity…A friend asked me, "Why do that? Don't they have the money?"…[C]ompanies like Meta, which can raise money from banks at low rates any time they want to, increasingly choose ... not to. Instead, they turn to private investment groups—private equity, essentially—who can create custom financing for the project. And for which the company pays a significant premium over investment grade interest rates. How much more? As much as 200-300 basis points, or 2-3%…

So, why would an investment-grade company [like Meta] agree to do that? They do it because the capital needed for these buildouts is so large that doing it with orthodox balance sheet debt, or by issuing sufficient equity, let alone spending your cash, would make a mess of your balance sheet…By structuring it this way, via special purpose vehicles (SPVs) in which they have joint ownership, companies like Meta don't have to show the debt as their debt. It is the debt of those guys over there, that SPV. Not us. Granted, they retain shared control, and they get to use the AI data center, and nothing there happens without their say-so, but still. It's not ours.

This is accounting trickery, of course. It is a transparent attempt to raise large amounts of money without balance sheet damage by putting the debt in a vehicle you indirectly control, but that, for accounting reasons, doesn't have to be disclosed as your debt on your balance sheet…

At the same time, an increasing percentage of private credit providers are funded, in part, by controlling interests in insurance companies, whose capital they use to fund investments. Finding investments that generate higher yields without higher risk—lending at above-market rates to companies like Meta—is exactly what they want to get higher yield while not running afoul of insurance regulators.

And while it all makes perfect sense as financial engineering, this is where the risks start. Why? Because this system creates a powerful incentive loop between structurally overcapitalized insurers, return-hungry private equity firms, and mega-cap companies trying to avoid looking like they're leveraging up. Everyone gets what they want—until something breaks.

That also sounds like a classic buildup of financial risks. The AI boom is a staggeringly huge one-way bet on a single technology. Sometimes, as with the railroads in the 1870s, a technology that really does end up transforming the world can still create a messy financial crisis along the way.

5. Macroeconomics is falling, microeconomics is rising

For my first few years as a blogger, I was primarily known as a critic of macroeconomics as a discipline. The data was far too patchy and confounded to warrant most of the strong conclusions that macroeconomists routinely proclaimed. And macroeconomists rarely tested the “microfoundations” (assumptions about consumer and corporate behavior) that undergirded their models. No one ever seemed to be able to draw a definitive conclusion in macro — a lot of it was all just about who could shout the loudest in seminars, or appeal to the right political opinions, or deluge their critics with a blizzard of equations. It was not very scientific.

Microeconomics, on the other hand, seemed a lot like a real science. Micro theory often really worked — auction theory gave us Google’s business model, consumer theory really could predict consumer behavior (and, often, prices), matching theory was used in a bunch of applications, and so on. And on the empirical side, the “credibility revolution” brought causal methods to the fore, allowing us to make good educated guesses about the effects of many policy changes.

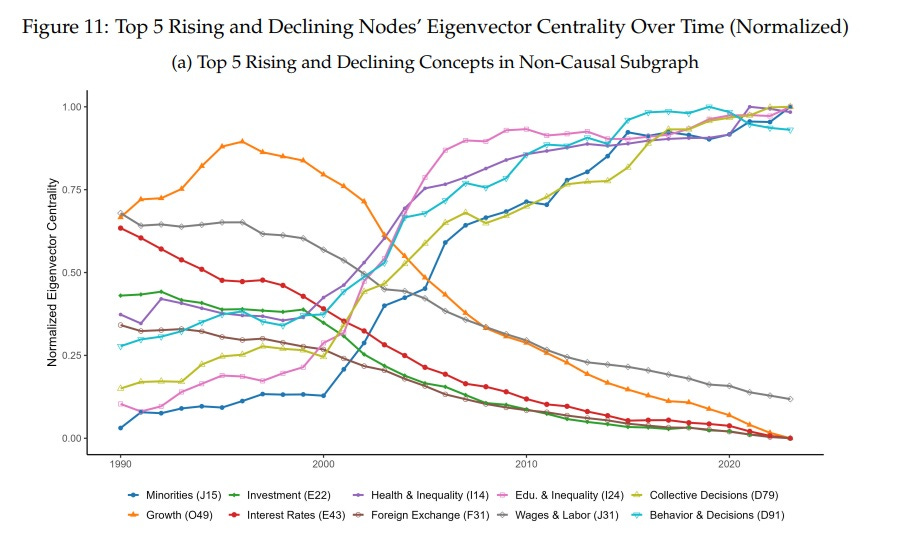

I found that most economists I talked to agreed with me on this basic divide. Now, a decade later, we have some data to show that economists as a whole have been walking away from the grandiosity of macro toward the humble reliability of micro. Garg and Fetzer (2025) use LLMs to analyze the topics of economics papers. Like other researchers, they find that causal empirical methods have been taking over the discipline since the 1990s. But they also note that macroeconomic topics have become steadily less “central” to econ research:

Don’t let the nerdy labels on the graph distract you here; this just means that the authors’ AI says that macro stuff is getting less important as the focus of econ papers, and micro stuff is getting more important, and that the big change happened since the late 1990s. (This chart is actually for papers without causal empirical methods; there’s another similar one for those with causal methods, and the pattern is the same.)

If you think economics chases current events, this could come as a shock. After all, the 90s and early 00s were the “Great Moderation”, where macro events seemed to matter less and less, while the years since 2008 have seen a once-in-a-century financial crisis, a long-lasting global recession, and the return of high inflation. Why are economists thinking less about macro, even as macro has become more important?

The obvious interpretation here is that economists, in general, are walking away from the temptation to spin big, unprovable theories about great big questions, and working on smaller, more answerable questions instead, making use of the new data and methods that the computer revolution has provided them. This suggests that most economists had the same realization I did, and they dealt with it by making their profession more humble and more scientific. Next time you feel the urge to declare that “economics isn’t a science”, remember how the field has changed.

6. A big YIMBY victory in California

In these roundups, I love keeping track of YIMBY political victories as they pop up. Last week we had a big one. California has a law called CEQA, which is basically a version of the national law NEPA but on steroids. CEQA basically allows NIMBYs to sue any development project for practically any reason — in Berkeley, some people sued to block a low-income housing development, on the grounds that college students who would live there are a form of human pollution. They lost, but the potential for such lawsuits exerts a huge chilling effect on development of all kinds, which is probably one reason California has gotten so unaffordable in recent decades.

Last week, Gavin Newsom signed two bills that will make CEQA a little less of a problem. Here’s a quick explanation of what the bills do:

The first bill, AB 130, expands existing exemptions for infill housing projects in urban areas. Under the revised law, housing projects on infill sites of up to 20 acres will be exempt from CEQA review if certain conditions are met…To be eligible for the expanded exemption under AB 130, an infill housing project must comply with zoning rules, must not be located in a sensitive habitat area, must not require the demolition of any structure on a historic register, and must not be used for temporary lodging (e.g., as a hotel).

The second bill, AB 131, establishes a simplified CEQA review process for infill housing projects that would otherwise not qualify for a CEQA exemption because of a failure to meet a single condition. Under the revised law, these projects will only need to analyze that single failed condition under CEQA instead of conducting a complete environmental review…Among additional changes aimed at streamlining the CEQA process for housing projects, AB 131 also (1) exempts from CEQA review any rezonings consistent with the housing element of a local government’s general plan, and (2) requires the Governor’s Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation to develop, by July 2027, a map of underutilized land within existing urban areas where new infill developments could be built.

As deregulations go, this might sound like small-bore stuff, given all the conditions and caveats. Chris Elmendorf, a UC Davis law professor who has been among CEQA’s most dogged and well-informed critics, believes that the news laws could speed up permitting times for housing in some urban areas by “a lot more than 25%”. And he praises the new laws for avoiding the onerous requirements (“bagel toppings”) that previous YIMBY bills in California had required.

So although it’s only a small start, this is a meaningful victory. And my favorite thing about was what Gavin Newsom said when he signed the bills:

And as Sam D’Amico points out, many of the legal changes apply to advanced manufacturing as well as housing. That’s excellent, and makes me a tiny bit more optimistic about California’s future.

7. How to solve mass incarceration

For years, many of us regarded America’s huge prison population as something that required policy changes to solve. But what if the problem ended up solving itself?

From the early 1990s to 2014 there was a huge crime decline in America. Violent crime started to inch up in 2015, and then had a sharp 2-year spike in 2020-21, but in the last few years it has been plummeting back down. And property crime continues its long decline.

As Keith Humphreys notes in The Atlantic, that crime decline is leading pretty mechanically to a drop in youth arrests:

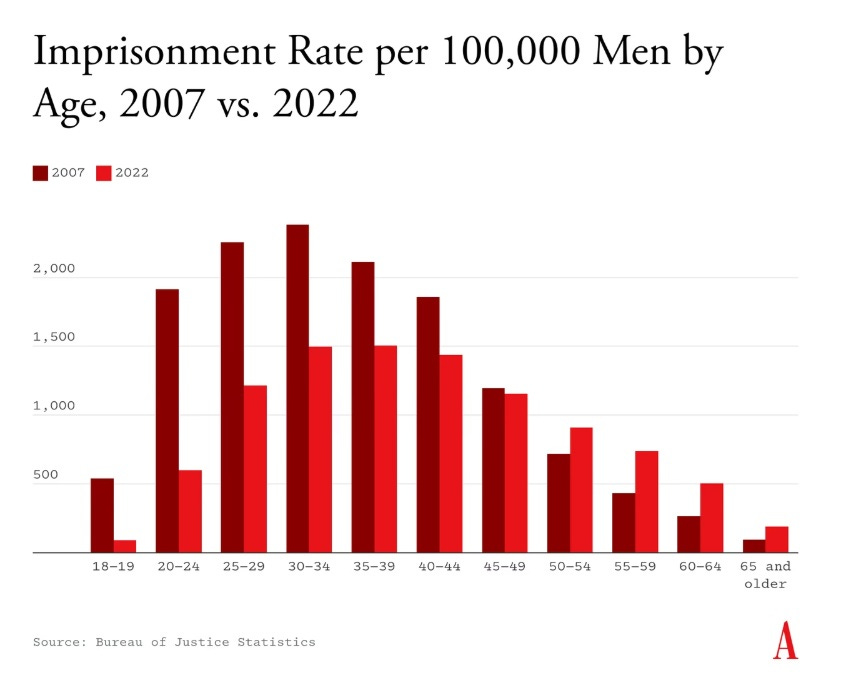

And as he also notes, this is leading to a huge drop in the imprisonment of young people:

Over the next few decades, much of the rapidly graying American prison population will die or be released, and — assuming crime doesn’t soar again — they won’t be replaced by fresh batches of younger criminals. America’s incarceration rate will plummet — not because we decided to be more lenient, but simply because there was a lot less crime for a very long time.

The way to solve mass incarceration is just to reduce crime.

One might even say he is the Chad.

A small exception was the run on a couple of crypto-focused medium-sized regional banks back in early 2023, but that was easily taken care of.

Of course educating women decreases fertility rate.

-They learn about birth control and the nature of fertility in general

-They become empowered

-They seek careers

-The forces of tradition/religion will have less influence over them

Every aspect of this will and does lead to fewer births.

I don’t get how you, post after post, can be so blind about this when you’re the type of writer whose whole thing is that he can see the signals through the noise: every single thing societies have done in pursuit of women’s advancement lowers the fertility rate. Legalizing abortion, de-emphasizing the importance of motherhood, promoting birth control, empowering women, educating girls, etc. These all may be positive things in various ways but they have a downside as well.

By all means, let’s find a way to keep women’s equality and also increase the birth rate at the same time. But at least be intellectually honest about it.

Noah, I’d like you to elaborate a bit more on why you think your next financial crisis is Crypto or AI versus our debt.

No, we have no idea when our debt will become a financial crisis, or are you saying that our debt is not a crisis? That we are more like Japan in that sense. we’ll have zombie banks and zombie country.