At least five interesting things to start your week (#10)

Where China went wrong, Millennials' economic success, AI and growth, Asian coalitions, and AOC's sunscreen crusade

I’m really enjoying doing these roundups. They help me get rid of the nagging sensation that I’m missing a lot of good topics.

Anyway, first, podcast. Here’s Brad DeLong and me on Hexapodia, discussing the fun question of why so many people perceive a good economy as bad:

Anyway, on to this week’s Five Interesting Things:

1. Did state control wreck China’s economic model?

It took a while, but the popular narrative on China is finally starting to shift. Whereas just a year ago the press was still largely filled with paeans to China’s awe-inspiring economic growth, now we see a lot of stories about how everything is going wrong:

China's…consumer prices dropped annually in July…JPMorgan strategists cautioned that China risks a 1990s-style "Japanification" if policymakers don't address the housing market, financial imbalances, and aging demographics…Manufacturing activity has contracted for four straight months…July exports declined at the sharpest rate in three years, at 14.5% annually…

Embedding Communist Party members in corporations and prioritizing state-run firms, [author Dexter Roberts] said, has dragged on domestic productivity, spooked the private sector, and made the country less attractive for foreign investment.

"A lot of companies now feel China isn't the market of the future," Roberts said…To that point, China's foreign investment gauge plummeted to a 25-year low in the second quarter…

From an unstable, debt-ridden property market to anti-business policies and demographic issues, Beijing has plenty to tackle if it hopes to match the same growth as decades past.

Writing in Foreign Affairs, Adam Posen declared “The End of China’s Economic Miracle”. Many long-time China watchers are taking the opportunity to say I-told-you-so.

So…what went wrong? Just a couple years ago plenty of people thought that China had figured out a new, better economic model. Why did it run off the rails?

In a larger, “macro” sense, it ran off the rails for a simple reason. In the words of Herbert Stein, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” Ultimately, diminishing returns to physical capital, combined with an increased burden of upkeep, make further mega-investment projects wasteful and useless. Ultimately, it’s no longer possible to bring people from the countryside to the cities. Ultimately, a developing country runs out of technologies that it can copy or steal from advanced countries, forcing it to start the much more cumbersome process of inventing new stuff on its own. China’s hypergrowth could not continue forever, so it did not.

The real question is why China’s growth decelerated when it was still only at 29% of U.S. per capita GDP. Some people will shrug and say well, China is a big country, and it’s harder for big countries to get rich. But the U.S. is a fairly big country as well, and it’s richer than almost all other countries. So I’m skeptical of this common, glib explanation.

Another explanation we see popping up a lot is state control. Posen writes:

After defying temptation for decades, China’s political economy under Xi has finally succumbed to a familiar pattern among autocratic regimes. They tend to start out on a “no politics, no problem” compact that promises business as usual for those who keep their heads down. But by their second or, more commonly, third term in office, rulers increasingly disregard commercial concerns and pursue interventionist policies whenever it suits their short-term goals. … Over varying periods, Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, Viktor Orban in Hungary, and Vladimir Putin in Russia have all turned down this well-worn road.

I think there is something to this. Xi has made a ton of mistakes, including Zero Covid, Belt and Road, and so on. I doubt that putting party apparatchiks in every company or making businesspeople spend hours every day studying Xi Jinping Thought is going to do much to help the economy either. But the fact is that Xi’s transformation of the Chinese economy into a giant reflection of his own cherubic face has not really had time to proceed yet; the mistakes Posen describes are very recent, and most of their effect likely hasn’t been felt yet.

I agree with Adam Tooze’s argument that China’s economic deceleration is all about the country’s real estate crash. Xi precipitated that crash, but it’s not really his fault; it was very long in coming, and stemmed from the fact that real-estate-related industries reached almost 30% of China’s GDP, far more than in other countries even at the peak of their own housing bubbles. And that in turn has its roots in China’s strategy of using real estate loans by state-controlled banks as a form of fiscal stimulus. This also lowered China’s productivity growth by diverting capital and labor away from other industries with better prospects for efficiency improvements. In other words, both China’s short-term and long-term economic problems stem from its over-reliance on real estate as an economic driver, a financial asset, a government revenue source, and a method of fiscal stimulus.

But that over-reliance on real estate does stem, in an important sense, from Chinese state control. It was state-owned and state-dominated banks, acting at the behest of the central government and local governments, that redirected so much of the country’s resources toward real estate. That control began long before Xi, but it does represent a failure of central planning nonetheless.

2. Yes, the typical Millennial is thriving

It’s good to see more people being skeptical of the narrative that the Millennials are a uniquely screwed generation, doomed to be poorer than their parents by high housing prices and high student debt levels and the scars of the Great Recession. You still see some folks advancing this narrative, such as a recent story by Julian Mark in the Washington Post. But more and more folks are pushing back, especially from the progressive side. Here’s Dean Baker:

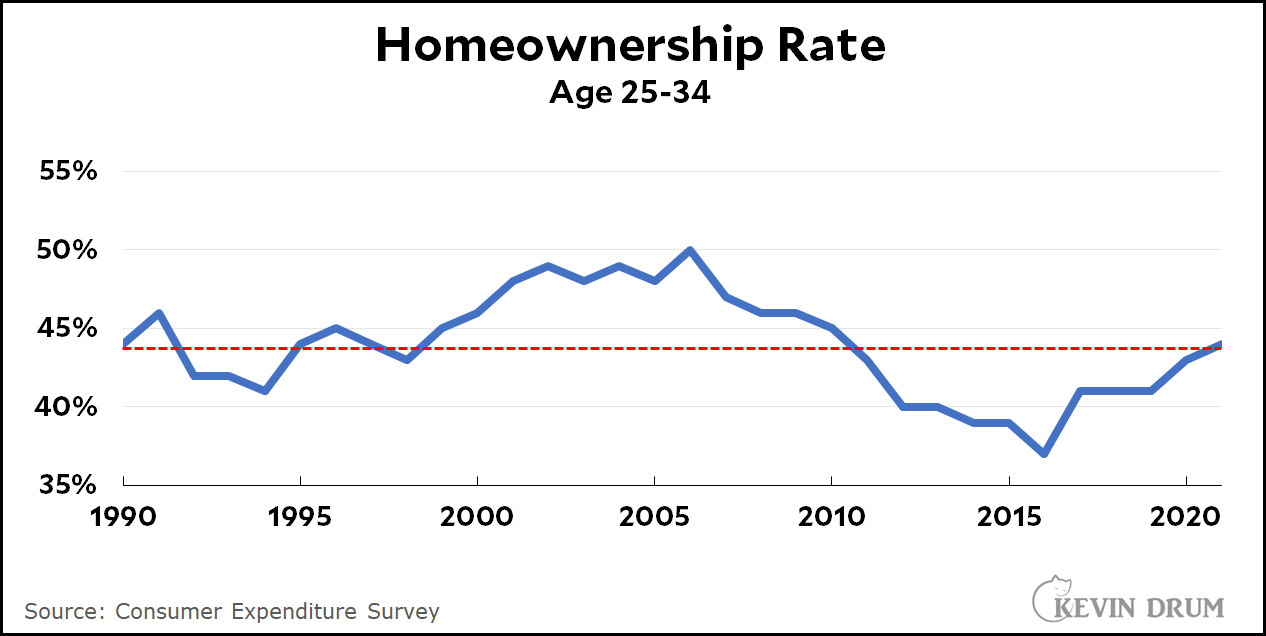

The Washington Post told readers that the current generation of young people is finding it much harder to become homeowners than young people did in the past. The data disagree with this claim…There is no doubt that the recent run-up in mortgage interest rates has made it much more difficult for first-time homebuyers, and if they stay anywhere near current levels we will likely see a drop in homeownership rates among the young. (The average for the first two quarters is already down slightly from the 2022 level.) However, the idea that the current generation of young people is finding it uniquely difficult to become homeowners simply is not true.

And here is Kevin Drum:

Millennials are doing fine. There's a small and vocal subset who are unhappy that they can't afford to live by themselves in a spacious apartment in Manhattan, but the vast majority are faring as well as previous generations and better than Millennials in any other country in the world. Someday a reporter from the Washington Post will read this and pass the news along to the rest of the country.

Here are a couple of great charts from Drum on homeownership rates and student debt levels:

For all the headwinds and disasters everyone talks about, Millennials are, economically speaking, a very average normal generation. I expect it to take at least a couple more years of economic success for this narrative to thoroughly replace the old one, though.

(Update: As some folks on the app formerly known as Twitter pointed out, this measure of the homeownership rate only counts people who are heads of their own household. More young people live with their parents than in the past — about 20%, compared to 12% in 1990. Taking this into account, and counting cohabiting couples the same as married couples, the homeownership rate for young people is maybe 3 percentage points lower than it was in the 1990s. If cohabitors aren’t counted as married, it’s 5 percentage points lower. Still, the difference isn’t huge, and the trend line since the mid-2010s is strongly positive.)

As a coda, one thing that irks me is that the way America’s housing system works makes it very easy to complain no matter what’s happening to housing prices and mortgage rates. If house prices are rising, you can complain about how hard it is for young people to afford a home. But if house prices are falling, you can complain about how middle-class wealth is being demolished (since most middle-class Americans have most of their wealth in their house). No matter what happens, you can tell a negative story about it. This is a product of the fact that America chose long ago to make real estate our main middle-class wealth vehicle, instead of stocks and bonds like they do in Japan. But in any case, I wish the people who complain about these things would imagine what their ideal situation for housing prices would look like.

3. A wonderful debate on AI and economic growth

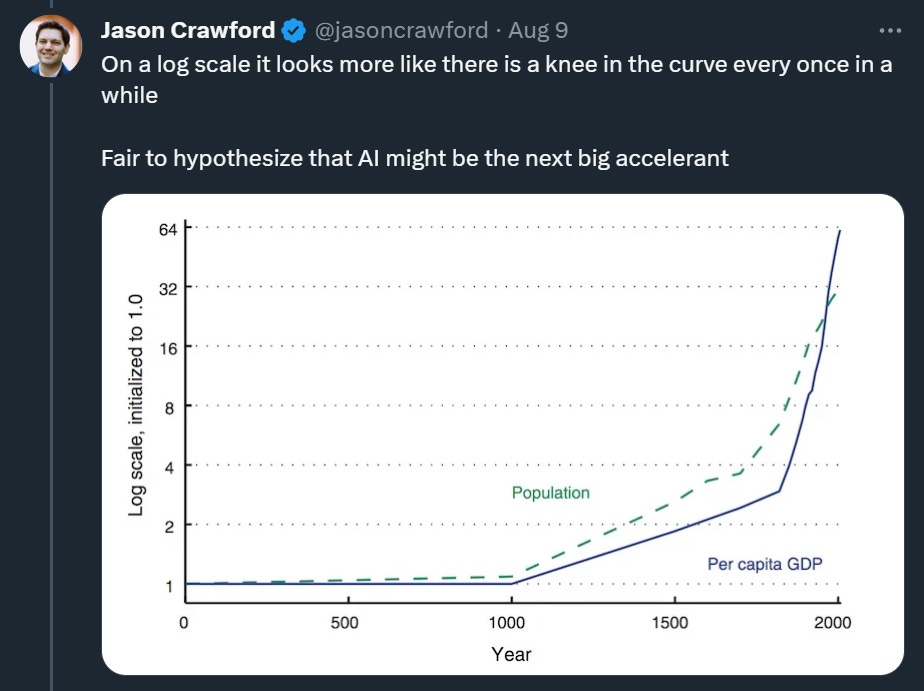

Some folks think the advent of the set of technologies we currently call “artificial intelligence” is likely to cause a discontinuous explosion in technological progress and, by extension, economic growth:

Others are skeptical. Obviously no one actually knows what will happen, but it’s interesting and fun to debate — not just because AI is cool, but because thinking about this issue forces us to think about the nature of technology, the requirements for innovation, and what makes economies grow in the first place.

Anyway, the most intelligent, well-informed version of this debate that I’ve yet seen — by a long shot — was the recent exchange between Tamay Besiroglu and Matt Clancy in Asterisk Magazine. You should really read the whole thing, but here are some summary bullet points:

Besiroglu thinks that that although current generative AI isn’t good enough to produce the kind of explosive growth he envisions, he thinks that future AI that’s good enough to replace essentially all human tasks will supercharge growth to 20% per year (compared to the long-term U.S. average of 2%). He cites previous growth accelerations as precedent for this.

Clancy is skeptical, pointing out that previous innovations like steam and electricity and computers were pretty amazing in their own right, but didn’t produce the kind of growth Besiroglu expects.

Besiroglu cites Paul Romer’s endogenous growth models as reason to believe in his own forecast — if growth depends on new ideas and AI can generate new ideas at very low cost, we’re in business. Clancy counters with a model by Aghion, Jones, and Jones (2017) that says that as long as some tasks still need to be performed by humans, human population growth will still be a constraint on the rate of innovation.

Besiroglu says that even if there are some bottlenecks, they will be few, and shifting to a world where most innovative tasks are done by AI will produce a long boom of very rapid growth. Clancy argues that previous waves of automation already automated quite a lot of innovative tasks, and we still only saw 2% long-term growth.

Besiroglu argues that AI’s contributions to innovation will be fundamentally different from previous technologies, since humanity will be able to throw exponentially increasing amounts of compute at the problem. Clancy notes that many tasks are physical tasks that can’t be solved with compute, that data presents a limitation in addition to compute, and that there are regulatory issues to deal with as well.

At this point the debate moves on to speculations about the capabilities of future AI systems.

This was a really wonderful debate, and both sides present reasonable arguments. In the end I have to give it to Clancy, if we’re talking about the current type of generative AI systems; data and compute both seem to provide hard limits that will stop LLMs and diffusion models from achieving infinite exponential growth, possibly within a fairly short time frame. But Besiroglu leaves himself an out by saying he’s talking about hypothetical future better AI systems, and here I think he has a point — if we ever do manage to invent intelligence that can do everything human brains can do but much better and much cheaper, then I think we might conceivably see the kind of acceleration he envisions.

4. Balancing coalitions are the future of Asia

China’s economy may have slowed down, but it’s still enormous — by many measures, the biggest in the world. It’s certainly the world’s biggest manufacturer, producing about as much in value-added terms as the U.S. and Europe combined. This makes it absolutely the “big fish” in the Indo-Pacific region, U.S. or no U.S.

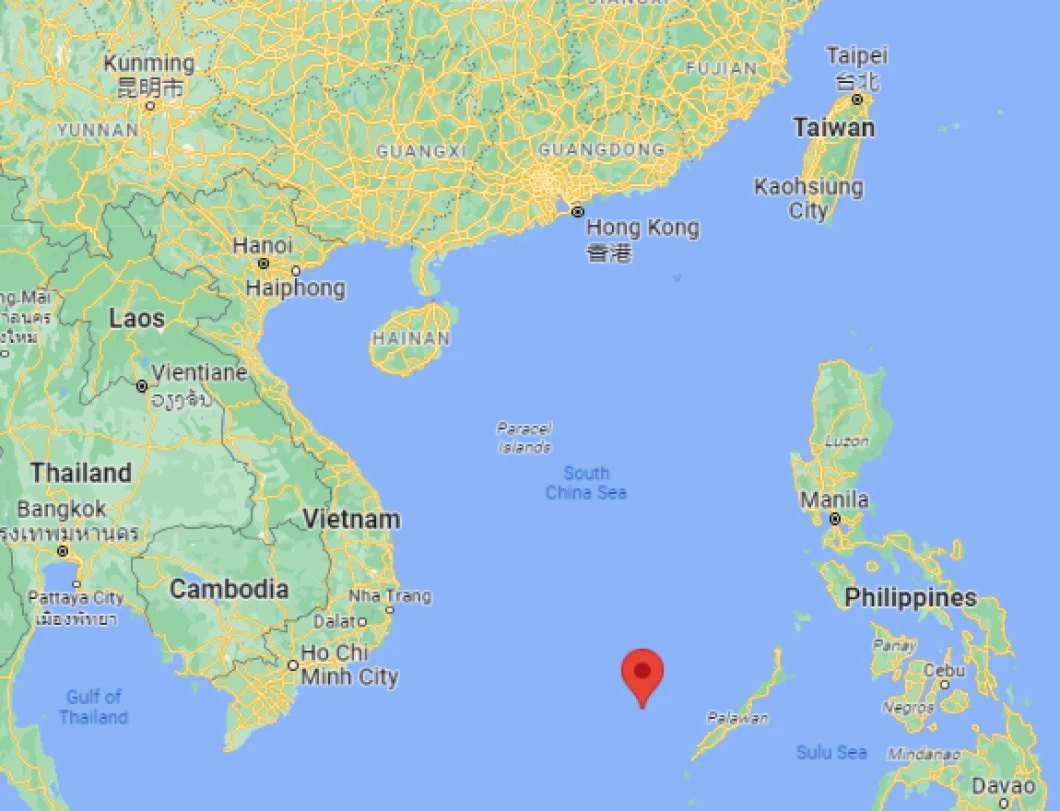

In recent years, China has become more bellicose with respect to most of its neighbors, which has contributed to plunging approval ratings in Asian countries. The most recent example was when a Chinese coast guard ship fired a water cannon at a Philippine fishing boat near a disputed area of the South China Sea:

China claims basically the entire South China Sea as part of its territory, even though the Permanent Court of Arbitration has rejected this claim. So actions like this clearly presage more to come, and indicate a general strategy of “salami slicing” on China’s part. You can see that the Second Thomas Shoal, where the confrontation took place, is very close to the Philippine island of Palawan, and pretty far from China:

Anyway, this is just one example; China’s incursions into Indian territory and Japanese waters and airspace are other examples, and its ships have similar confrontations with Vietnamese boats.

The natural response to this increasingly aggressive posture is to form balancing coalitions. Traditionally, these have been so-called “hub and spoke” alliances between individual Asian countries and the United States. But with the U.S. somewhat occupied in Ukraine and looking less politically stable after the Trump era, Asian countries are starting to hedge their bets by forming an increasingly dense web of partnerships with each other. A few of the most recent examples:

The Philippines and Vietnam are signing an agreement to increase maritime cooperation in the South China Sea.

Relations between Japan and South Korea, which were frosty for many years, are now thawing rapidly as they unite to take on the challenge from China. Biden is hosting a summit at Camp David to encourage further cooperation between the two.

India is considering greater cooperation with Taiwan. Several retired Indian military chiefs recently visited Taipei, and the Indian military is beginning to plan its response to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

These countries are also looking to strengthen cooperation with the U.S., with Vietnam about to host Biden, the Philippines opening a bunch of new joint bases with the U.S. (in areas near to Taiwan), and India rapidly increasing military cooperation with America. And Taiwan is finding a few more friends in Europe these days as well. But it’s the intra-Asian partnerships that really signal a new era of balancing against China. We’re not yet near the point of an Asian NATO equivalent, but we’re slowly headed in that direction. The U.S. should now focus on increasing economic ties with Asian countries, and between Asian countries, in order to solidify the emerging web.

5. AOC and the new progressive deregulation

I recently spent seven days in Japan, walking around under the blazing summer sun. Luckily, I had excellent high-SPF Japanese sunscreen to counter it. In a recent Instagram video, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez appeared with skin care entrepreneur Charlotte Palermino to complain about the fact that these advanced sunscreens aren’t available in the U.S. The reason, in a nutshell, is regulation:

"US sunscreens are far behind the rest of the world," said Ocasio-Cortez. "I was in South Korea earlier this year and it is so clear how far advanced the rest of the world is on sunscreen, and we deserve better in the US."

The United States, namely the FDA, regulates sunscreen as a drug, not a cosmetic product…[which] adds a ton of regulations to the process, not to mention time and money. "Sometimes that can add a lot of bureaucratic and cost that prevents us from getting any sunscreen filters at all," said Ocasio-Cortez.

According to both Ocasio-Cortez and Palermino, the US sunscreen filter hasn't been updated since 1999. Think of how much beauty has changed since then! Ocasio-Cortez also cited a 2017 study that found only half of US sunscreens measured up to European protection standards…

Because of tighter regulations in the US, it can be difficult to get new ingredients approved…[T]he approval process is a lot faster in other countries, leaving the US in the dust, formula-wise.

Online socialists rabidly attacked AOC over the video, but this just shows how out of touch they are. Americans, by and large, don’t care about leftist ideological crusades; they want products that will preserve their skin and protect them against cancer. And due to our creaky, cumbersome regulatory state, they aren’t getting them. AOC’s populist instincts are good, and the online socialists are irrelevant.

This episode demonstrates that progressives are starting to think harder about deregulation. Among leftists, deregulation is ideologically verboten, but progressives are a much more pragmatic lot, and are beginning to realize that while many regulations are good, some stand in the way of progressive goals. There’s nothing inherently virtuous about regulation, and when it prevents us from getting good sunscreen, or power lines, or solar panels, we should loosen it up. Targeted deregulation needs to be part of the new industrial policy framework that progressives are building, and it’s great to see savvy politicians like AOC thinking along these lines. The Biden administration is, too; as reader Pablo Alvarez pointed out last week, the President is now pursuing NEPA reform. Good. I plan to write more about the specifics of that in the coming days.

I’ve got to be careful how I talk about this due to NDA’s, but I’ve got first hand experience integrating AI into production lines in boring parts of the economy. I tend to think the role of AI is under appreciated in fueling future growth. But I don’t think it will be because of chatGPT models. There are a lot of more fundamental parts of the economy with highly technical aspects that will drive growth. Some hypothetical examples:

1) AI-driven alleviation of administrative burden (e.g. automated reading of forms, automated ID verification, etc.)

2) Signal processing, where AI can make a best guess of missing parts of a spectral signal to keep transmission humming

3) Micro-grid software, where AI can apportion energy use and estimate power output from power plants. As EVs are adopted, they can also estimate which portions of an existing grid should be prioritized for upgrades.

4) Manufacturing decision making, which shrinks the gap between problem presentation and solution for in-line processes.

None of these have the appeal of say, asking your computer to turn a family photo into a Picasso painting or having chatGPT adopt Tolstoy’s War and Peace for the wizarding world. But they are more likely to leave an impact. What’s more, the advances in consumer AI tend to outpace the use of highly technical AI. So as cool as chatGPT is, it vastly exceeds the AI applications in industry today. As such, I don’t think the current generation of AI techniques is baked in yet, and the current generation is moving fast.

20% growth is a huge overshoot for AI predictions. Ideas are useful, but we can see growth rates where the ideas are already there and just need to be implemented. This is what the developing world does; they copy existing models which is how they get such fast growth--textiles; steel; cars; electronics; etc. but maybe 9%, not 20%.