At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#35)

Chinese defense spending, activists vs. normies, corporate diversity, phones in schools, the noncompete ban, and rising inflation

Posting was a little bit sparse this week, due to some conferences that I went to. As a result, the number of things I want to write about is piling up fast! So I might do a few more roundups than usual, just to get to them all.

My podcast with Erik Torenberg, Econ 102, is evolving into a Q&A podcast, where people ask me questions and I respond as quickly and informatively (and, hopefully, entertainingly) as I can. If you have questions you’d like me to answer, you can submit them to the podcast producers at Econ102@turpentine.co. Here’s this week’s episode, which featured questions on a wide array of topics:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things!

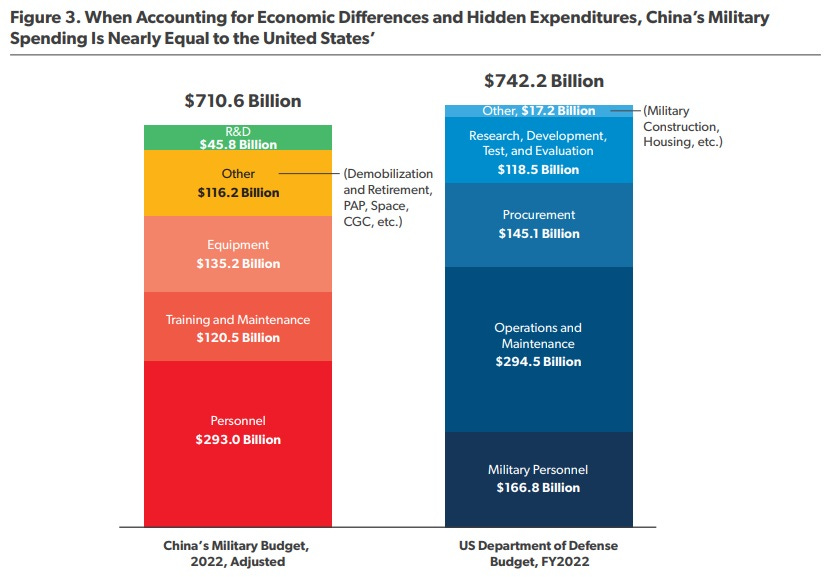

1. China spends about as much as the U.S. on defense

One talking point that you hear a lot in discussions of defense spending, especially from progressives, is that the U.S. spends as much on its military as the next 9 countries combined. And if you take these numbers at face value, it’s true — on paper, the U.S. vastly outspends its main rivals, China and Russia.

But the talking point is wrong, and these numbers are deeply misleading, for two reasons. First of all, these numbers don’t take into account the relative price differences between countries; soldiers’ salaries, military hardware, etc. cost a lot less in China than they do in the U.S., so China gets far more bang for its buck. Second, China does a lot of its military spending off the books, so the official numbers you see in charts like the one above are really just fake.

The people who argue against defense spending know this, of course, and just refuse to admit it or talk about it. But in the defense community, everyone talks about it openly, and there are many attempts to estimate how much China actually spends on its military. Many of these take either price differences or off-budget spending into account, but not both. An estimate by the U.S. intelligence community last year took both things into account, and came up with a number of $700 billion — almost as much as the U.S. spends. But the methodology wasn’t released to the public.

Now the American Enterprise Institute has done their own analysis, with a very transparent methodology, and they’ve come up with a number very similar to what the intelligence community found:

You can of course quibble with these numbers a bit, but the broad fact should be clear: Chinese military spending is in the same ballpark as U.S. spending, once you take price differences and off-budget items into account. Even if the numbers are a little bit off, simply performing this exercise should decisively kill the talking point that the U.S. outspends its rivals on defense by a huge amount.

AEI’s analysis also shows a huge potential area for cost savings in the U.S. defense budget — “operations and maintenance”. A big reason America spends so much on defense is that we’re keeping our military active. The U.S. military is fighting pirates, fighting random little local terrorist groups, doing various patrols, and so on — basically, being the World Police. If we want to divert defense spending to military modernization and the revival of the defense-industrial base, we’re going to have to stop asking our military to do so much on a day-to-day basis.

2. The activist kids are just part of the New 1970s

A key part of my “New 1970s” thesis is the idea that as the bulk of the American populace calms down from the unrest of the 2010s, a hardcore activist fringe will take the ideas of that turbulent decade to ever greater extremes. And indeed, anecdotes suggest this is happening; a loud but fairly small cohort of Palestine protesters are occupying college campuses, while regular people are paying attention to more mundane things.

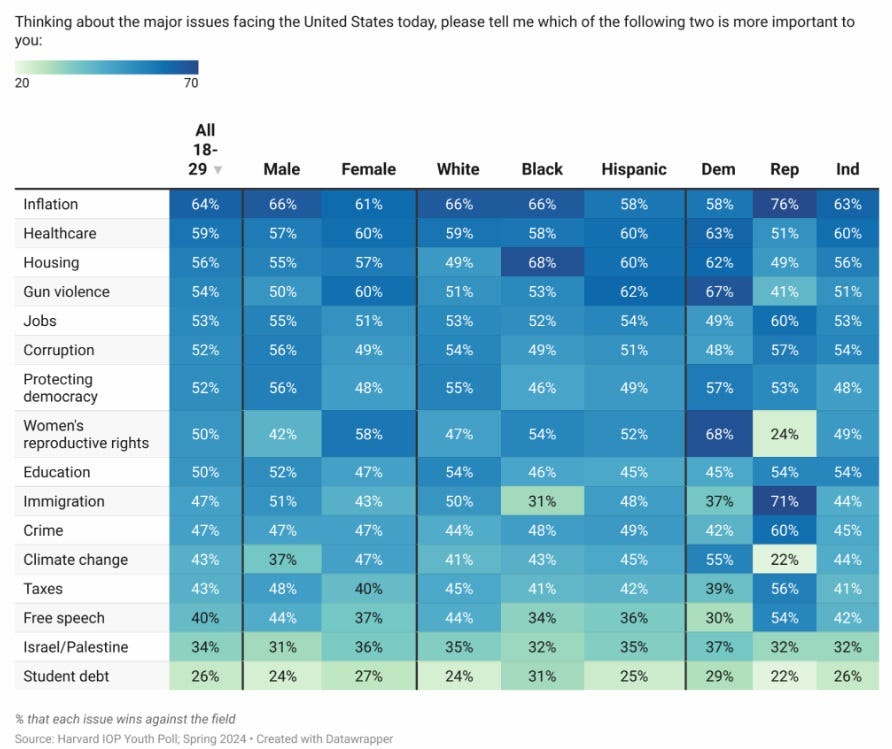

But we don’t just have to rely on anecdotes to observe this divergence; we have some data. A recent high-quality survey by the Harvard Institute of Politics (not to be confused with the lower-quality Harvard Harris poll) studied the opinions of Americans age 18-29, and found that most of them don’t place that a high of a priority on activist causes like Palestine or student debt forgiveness. Even climate change ranks far behind humdrum bread-and-butter issues like inflation, health care, and housing in young people’s minds:

So while a smallish, loud, active group of youngsters is fighting the cops and making tent encampments for Palestine/revolution/socialism/whatever, most young people just want cheaper rent and health care.

That’s good news for decreasing U.S. unrest. The issue, as Nate Silver and Matt Yglesias write, is that the people who run the Democratic party don’t mingle much with the average youth, so they tend to get their ideas about what young voters want from the activists who bang on their doors (or join their staff). Thus, Democrats have a tendency to emphasize issues like climate and student debt forgiveness in their messaging and policy. This focus on issues that most Americans consider of secondary importance probably ends up turning off older voters who are much more likely to turn out and vote.

On climate change, I don’t think this is much of a problem, actually. Americans care about climate way too little, so activists have actually done a good job by pushing older progressive elites to focus on the problem. And the practical result of the climate focus will be to revive industrial policy and American manufacturing, and hopefully get us some reform of permitting and other outdated regulatory red tape. So that’s good. Meanwhile, on Palestine, Democrats have basically ignored the activists, though they might cause disruption at the presidential convention this summer.

It’s on the student debt issue that I think Yglesias and Silver have the strongest case. Student debt cancellation — which, under Biden’s plan, is a permanently repeating thing — is incredibly expensive, and it represents a subsidy to a service industry that’s already overpriced. That’s very wasteful spending, and as Yglesias and Silver note, it’s probably not going to turn out the youth vote very much if at all. So this is one issue where Democratic legislators should value polls over activists.

3. New evidence on the effects of corporate diversity

In the 2010s, there was a big battle over diversity as an ideal. A common progressive claim is that diversity improves the performance of corporate teams. Some papers do in fact find this, and there’s a theoretical rationale behind it too — people from different backgrounds, with different ideas and skills sets, might be able to combine their diverse sets of perspectives and skills to solve problems more effectively than teams where everyone is basically similar. Belief in this effect was one reason for the rise of DEI — although there were many other reasons, too.

But a new paper by Walrich et al. casts serious doubt on this claim. It’s a pre-registered meta-analysis that takes a bunch of studies into account. The paper considers a wide array of different types of diversity — demographic, job-related, cognitive, and so on. It considers the effects of diversity in a wide range of occupations, tasks, and settings. And it considers a variety of mechanisms by which diversity might improve team performance.

And it finds that the effects of diversity are very small:

Here, we provide a new comprehensive, meta-analytic summary of the growing literature that considers the state of the evidence across disciplines, countries, and languages. We conducted a reproducible registered report meta-analysis on the relationship between diversity and team performance (615 reports, 2,638 effect sizes). We found that the relationships between demographic, job-related and cognitive diversity, and team performance are significant and positive, but insubstantial (|r| < .1). Even considering a wide range of moderators, we found few instances when effects were substantial – though correlations were more positive when tasks were higher in complexity or required creativity and innovation, and when teams were working in contexts lower in collectivism and power distance. Contrary to expectations, the link between diversity and performance was not substantially influenced by teams’ longevity or interdependence. Further research will need to assess how contextual factors such as psychological safety and team’s virtuality affect the diversity-performance link. The main results appear to be robust to publication bias.

The basic story here isn’t “diversity is bad”, nor is it “LOL, nothing matters”. Instead, the lesson is that diversity is often slightly positive, but doesn’t make a huge difference. And there are a few settings and tasks where diversity does seem to be especially helpful.

This might come as a disappointment to DEI proponents, but not a huge one. It means that they’ll have to use other justifications for diversity programs in corporations; but they already have many other justifications, so that’s not a problem. Opponents of DEI should probably be more disappointed in these results, since they fail to find any evidence that diversity reduces team effectiveness or breaks the bonds of trust between team members.

As for me, I can’t say I’m particularly surprised here. My prior is that everyone in America is pretty professional in corporate settings, and that everyone works together pretty well and tries pretty hard regardless of demographics or background. This paper doesn’t do much to alter that basic intuition.

4. Phones in school are bad for kids

I tend to be pretty favorable to the evidence that smartphones have been responsible for a large number of psychological problems and social ills in America over the last decade. But I will be the first to admit that the jury is still out — the evidence is still not enough to draw firm conclusions in most areas. There’s one area in particular, though, where smartphones pretty clearly have a negative effect, and that’s on students’ ability to learn in schools.

Matt Yglesias has actually been banging this drum for quite a while, and I encourage you to read his post on the topic:

In particular, he lists some evidence in favor of the proposition that phones in classrooms reduce learning:

A small sample study by Melissa Huey and David Giguere found that when some college students were randomly assigned to have their phones physically removed before class, their mindfulness and comprehension of the course material went up…[A]nother interesting result from the study is that the phone-free students reported somewhat less anxiety…

UNESCO reports that students get distracted by phones, that task-switching is cognitively costly, and that, in particular, weaker students’ problems are compounded by distraction.

Now we can add a new piece of evidence to the growing list. Sarah Abrahamsson of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health studied what happened to schools in Norway that banned cell phones in classrooms, and found positive effects:

I show that banning smartphones reduces the number of consultations for psychological symptoms and diseases at specialist care, by about 2–3 visits during middle school years…[T]his is a significant decline by almost 60% in the number of visits…

[G]irls exposed to a smartphone ban from the start of middle school make gains in GPA, average grades set by teachers, and externally graded mathematics exams. Post-ban girls gain 0.08 standard deviations in GPA, and 0.09 standard deviations in teacher-awarded grades and have 0.22 standard deviations higher mathematics test scores compared to girls not exposed to a ban[.]

These are substantial effects, but not huge, and they seem to operate only for girls (for reasons the author speculates on but doesn’t really know). The result implies that phone bans would have a moderate positive impact on grades and psychological well-being for young girls.

The psychological angle is important here. If smartphone bans in classrooms were a way of forcing students to learn more at the expense of their emotional health, parents and teachers might reasonably conclude that the tradeoff isn’t worth it. But since smartphone bans in classrooms appear to improve grades and emotional well-being, it seems like kind of a no-brainer.

In his post, Yglesias points out that the idea of banning smartphones in classrooms is already widely popular among teachers, and in places where bans have been implemented, the results seem to be good.

Being a techno-optimist doesn’t mean that we should be in favor of every possible use of technology. Instead, it means believing that humanity can learn to use new technologies for its ultimate benefit. Putting guardrails on where and when a technology can be used is a standard method by which human society figures out how to use that technology — we don’t drive cars on lawns, or do karaoke in the middle of business meetings. Putting away smartphones during class seems like yet another thing that we’ll look back on as obvious half a century from now.

5. The assault on noncompetes

Lina Khan’s FTC did something that a lot of people — including myself — have been calling for for a very long time. It banned noncompete agreements, on the grounds that they’re an illegal anticompetitive practice:

Under the FTC’s new rule, existing noncompetes for the vast majority of workers will no longer be enforceable after the rule’s effective date. Existing noncompetes for senior executives - who represent less than 0.75% of workers - can remain in force under the FTC’s final rule, but employers are banned from entering into or attempting to enforce any new noncompetes, even if they involve senior executives. Employers will be required to provide notice to workers other than senior executives who are bound by an existing noncompete that they will not be enforcing any noncompetes against them…

The Commission found that employers have several alternatives to noncompetes that still enable firms to protect their investments without having to enforce a noncompete…Trade secret laws and non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) both provide employers with well-established means to protect proprietary and other sensitive information. Researchers estimate that over 95% of workers with a noncompete already have an NDA…The Commission also finds that instead of using noncompetes to lock in workers, employers that wish to retain employees can compete on the merits for the worker’s labor services by improving wages and working conditions…

Once the rule is effective, market participants can report information about a suspected violation of the rule to the Bureau of Competition by emailing noncompete@ftc.gov.

Now, it’s not yet clear if this new rule will hold up in court — the FTC has not exactly been on a legal winning streak lately. And there’s an argument to be made that this step would have been better as an act of Congress than as a regulatory decision. But from a purely economic standpoint, this decision seems like a very good one.

I used to write about noncompetes a fair amount when I was at Bloomberg. The evidence seems to be pretty clear that these clauses hurt workers in a variety of ways. Here’s Starr et al. (2023):

Our empirical approach…examines the labor market effects of higher incidence of enforceable noncompetes on the entire labor market (the constrained and the unconstrained)…We then isolate the pure externality effects of increased incidence of enforceable noncompetes on unconstrained individuals alone…The results indicate that job offers, mobility rates, and wages are all lower in state-industries where the use and enforceability of noncompetes are higher. [I]n states with greater noncompete enforceability, an increase in the proportion of constrained individuals reduces the relative rate of job offers, mobility, and wages, even for the unconstrained. (emphasis mine)

Higher wages are good, of course, especially if they reflect worker compensation being commensurate with productivity. But the effect on worker mobility shouldn’t be ignored. When workers are legally prevented from moving from bad companies to good ones, it reduces reallocation of labor. The U.S.’ ability to reallocate labor is an important reason why it’s richer than most of the countries in Europe and East Asia. This is excerpted from a recent IMF report:

So-called allocative efficiency measures the extent to which capital and labor are allocated to an economy’s most productive firms…A decline in allocative efficiency, whereby resources become more concentrated in relatively unproductive firms over a period of time, can reduce TFP growth; an improvement in allocative efficiency, as resources move toward more productive firms, will, however, boost TFP growth…

The approach used here…finds that allocative efficiency declined during 2000–19 in most countries in a sample of 15 advanced and 5 emerging market economies…A notable exception is the United States, where improvements in allocative efficiency helped boost annual TFP growth by 0.8 percentage point over the period.

Worker mobility also allows ideas to flow more freely between companies, raising the productivity of all the companies in an industry and enabling greater recombination and cross-pollination of ideas. A 2015 OECD report noted that in recent years, the top companies in many industries have pulled away from the rest, suggesting that their technological and business know-how is remaining trapped inside the companies.

Given that noncompetes both suppress wages and constitute a restraint of trade, a ban on them seems like something progressives and libertarians could agree on. But not everyone thinks the ban is a good idea. Here’s Tyler Cowen in Bloomberg:

In the absence of noncompete agreements, firms would be more likely to “silo” information — becoming less efficient and less able to pay higher wages…

Or say you are a sales company with a customer list, or a nonprofit with a donor list. An employee who sees those lists could use that information to start a competing business, or take that information to competitors. It seems reasonable in such cases to restrict the ability of employees to “jump ship.”…

If noncompetes are banned outright, to repeat, the effect will be less information-sharing within the company. New workers in particular, who have not demonstrated their long-term loyalty, will have a hard time getting access to information and getting ahead. More senior employees will have the advantage, hardly a formula for boosting economic opportunity.

A more general principle applies: Employers will invest more in training their workers if they know their workers cannot easily take those skills to their competitors.

This is a downside worth worrying about — especially the part about companies potentially being less willing to invest in worker training. In fact, there is some evidence for this.

But as Ryan Nunn reports, noncompetes cause a host of other problems that probably outweigh the benefit of greater training:

What do we actually observe? There is limited evidence on all of these points, but what research we do have suggests that stringent non-compete enforcement is associated with somewhat more worker training (Jeffers 2019; Starr 2019). It may also be associated with more investment at incumbent firms (Jeffers 2019), but this is offset by diminished firm entry and startup performance (Ewens and Marx 2017; Jeffers 2019; Samila and Sorenson 2011)…NCAs and/or relatively stringent NCA enforcement appear to have negative spillovers for entrepreneurship (Ewens and Marx 2017; Starr, Balasubramanian, and Sakakibara 2017), innovation (Belenzon and Schankerman 2013), and the mobility of workers who do not have NCAs (Starr, Frake, and Agarwal 2019).

As for Tyler’s concern that information-sharing withing companies will fall if noncompetes can’t keep employees locked up, the experience of the tech industry in California seems to provide a reason not to be worried. In California, noncompetes have long been unenforceable, and some scholars give this policy partial credit for the rise of Silicon Valley. In the tech industry, the spread of ideas across companies seems more important than the spread of ideas within them, and I can’t see a clear reason why other industries would be different.

So some kind of action against noncompetes seems warranted. Whether this was the right one is up for debate, but I suppose we’ll see how it turns out.

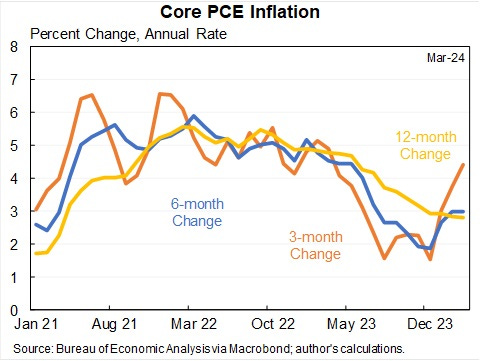

6. Inflation is rising again in the U.S.

I’ll close this roundup with some somber macroeconomic news: Inflation appears to be re-accelerating.

For more data, check out Jason Furman’s thread of updates. Inflation measures are rising pretty much across the board.

What’s going on? Shipping disruptions in the Red Sea due to the Houthi militia are one possible factor. But the San Francisco Fed reckons that the bulk of inflation in March was due to demand-based factors:

With interest rates having gone up, and pandemic savings having been largely spent, a potential remaining cause of demand-driven inflation is the federal government’s deficit spending — or as advocates of higher deficits like to call it, Big Fiscal.

It generally takes months for higher inflation to filter through to public opinion, so this burst of inflation might not come in time to sink Biden in November. But by engaging in big-ticket spending items like student debt relief at a time of elevated inflation, the administration is playing a dangerous game.

Regarding item 1: in the past, you’ve noted the advantages conferred upon armies by doing actual fighting. Eg, the Russian army majorly sucked in the earlier stages of the Ukraine invasion, but they now have much more fighting experience and this has levelled up their abilities. While the US is spending money on countless ongoing operations around the world that could no doubt be diverted to rebuilding its industrial base, is there not a sense in which these operations are keeping at least some elements of the military match-fit for future, more serious fights?

Thanks Noah, love your blog and your podcasts!

> the lesson is that diversity is often slightly positive, but doesn’t make a huge difference

Doesn't seem so. The abstract you quote conflates several unrelated things: "demographic, job-related and cognitive diversity".

Corporate DEI initiative do not demand and often don't even allow cognitive or job-related diversity. Corporate diversity always means more black women and fewer white men. The word has no other meaning and it's deceptive of the study authors to pretend it does. From their discussion section: "what we found broadly supports the contention that diverse cognitive resources have value, while contrasting social identities are less beneficial". They go on to state that ethnic diversity had no impact on team performance.

So if we ask the most biased people in the world to summarize their own beliefs, even they can't really find that diversity as practiced in the real world has benefits. Amusingly their data also appears to say that higher education doesn't work (educational level is one of the kinds of diversity that has no impact on team performance), which is a bit embarrassing.

I doubt they can properly measure any of this. A lot of positions created by diversity programmes are deliberately low skill, non-essential jobs for which success is subjective. How do you judge the impact on team performance of useless people who do nothing? You can't honestly say it's zero, because the resources used for such people could have been used to hire competent contributors instead.

I think for those of us who have actually experienced corporate DEI directly, we don't need hundreds of low quality studies on the topic. We already know the truth: what they call diversity initiatives are purely ideological race/gender pogroms which enforce total cognitive conformity whilst rapidly destroying team performance, morale and they can even wreck entire companies. The idea there's no impact is crazy for those of us with real world experience of it.