America's mayors are right to support small business

Supporting the middle class, shoring up support for the system, and restoring the lifeblood of our cities.

I’ve been pretty critical of Zohran Mamdani’s ideas for New York City. His plan to make buses free would degrade the quality of public transit and make it both less useful and less popular. His idea to open government-run grocery stores would just fail outright. His rent control plan would at least partially undermine his housing plans, while his proposed tax increases would probably accelerate the exodus of New York’s crucial finance industry.

But at least one of Zohran’s ideas is excellent: His support for small business. In a recent video, he promised to make it “faster, easier, and cheaper” for small retail businesses to open in NYC, to cut fines and fees for these businesses by 50%, to accelerate permits and applications, to slash regulations, to have government workers who help small businesses navigate government requirements, and to increase funding for small business support programs by 500%. Many of these ideas are listed on Mamdani’s website.

Mamdani’s push to support small business is part of a larger overall theme within America’s revitalized socialist movement, and within modern progressivism in general — a deep suspicion of big corporations and an instinctive support for mom & pops. It’s not just movement progressives, either. Daniel Lurie, San Francisco’s mayor, is widely regarded as a centrist, and yet he has made support for small retail businesses a keystone of his approach to urban revitalization:

Mayor Daniel Lurie today signed five ordinances from his PermitSF legislative package, driving the city’s economic recovery by making major structural changes that will help small business owners and property owners secure the permits they need more easily and efficiently. Reforms include common-sense measures to support small businesses through the permitting process, boost the city’s nightlife businesses, help families maintain their homes, and increase flexibility to support businesses downtown.

And here’s what he tweeted back in May:

No more permits for sidewalk tables and chairs—putting $2,500 back in the pockets of small businesses and saving them valuable time…No more permits and fees to put your business name in your store window or paint it on your storefront…No more trips to the Permit Center to have candles on your restaurant’s table…No more rigid rules about what your security gate must look like so businesses have more options to secure their storefronts…No more long waits or costly reviews for straightforward improvements to your home, like replacing a back deck…And we’re getting rid of outdated rules to give downtown businesses more flexibility with how to use their ground-floor spaces—because if adding childcare centers and gyms will help bring companies and employees back downtown, we should support it…In addition, every city department involved in permitting will track timelines and publish them online…Learn more about the initiative at https://sf.gov/permitsf

I’m extremely happy about this trend. To be frank, there’s not much to like in the model of progressive local governance that has emerged over the last two decades. Cumbersome regulations that slow construction and raise costs, public money funneled to useless or corrupt nonprofits, permissive policies toward crime and disorder, and weakening public education in the name of “equity” have all sadly become part of the standard progressive package, with predictably terrible results. (Lurie is known as a “centrist” because he has tried to rectify at least some of these problems.)

But the emerging support for small business is a very important bright spot! First of all, it’s an example of progressives supporting productive enterprise, rather than treating every type of human activity as an opportunity for ad-hoc redistribution. Progressives talk endlessly about “resources”, but the pool of resources in a city is not fixed. If you make buses scary to use by allowing disorderly people onto them, or if you limit new housing construction with regulation, or if you outsource city services to less competent nonprofits, the total amount of your city’s resources goes down, and there is simply less to go around.

But small businesses increase a city’s total resources, because they are productive enterprises. Every restaurant means a greater variety of food to eat, every boutique means a greater selection of clothes to wear. They’re an incredibly important component of capitalism, providing productive employment for almost half of all private-sector workers.

At this point, some hard-headed conservative is going to pop up to inform me that small business is inherently less efficient at production than big business. And this is generally true. Economies of scale are a real thing — when you can leverage the distribution networks and high volumes of Wal-Mart, you can afford to charge consumers lower prices than a corner bodega that doesn’t have those advantages.

That’s why big chain stores tend to drive mom-and-pop shops out of business when they come to town. When chains drive out small businesses, productivity goes up significantly — in fact, Foster, Haltiwanger, and Krizan (2006) estimated that this was the main source of productivity growth for the U.S. retail industry in the late 20th century.1

And yet when small business dies, something important is lost. For one thing, an important path to the middle class is closed off. Small business provides a lot of employment, but the class whose lives are transformed the most are the business owners themselves. This is from a 2014 report by the Urban Institute:

Family-business ownership is associated with faster upward mobility than observed in paid work once selection is addressed….[We find] a positive and significant [causal effect] on family-business ownership, where the outcome is upward income mobility from 1980 to 1999…[Our results] suggest that family-business ownership led to a higher level of economic advancement relative to working for someone else in the 1980s and 1990s. Owning or having a management stake in a small business had an unambiguously positive effect on upward income mobility during the 1980s and 1990s after controlling for resources in the 1970s.

This is the reason for Japan’s legendarily staunch support of small retail businesses. The country offers small businesspeople a dizzying array of cheap loans, tax incentives, subsidies for technological upgrading, free training and education, expedited permitting and regulatory approval, startup subsidies, various place-based policies, protection from competition by large chains, and so on.

Small business is considered a key pillar of the Japanese middle class, and also an escape hatch for independent-minded Japanese people to escape the often stifling corporate system. Altogether, small businesses of all types are responsible for 70% of Japanese employment, which is significantly higher than in the U.S. This preponderance of small business has probably held back Japan’s productivity to some degree, but it’s a sacrifice the country has been willing to make.

In the United States, small business is especially important as a ladder of upward mobility for immigrants, as anyone whose immigrant ancestors owned a convenience store, a furniture store, or a gas station can attest. Immigrants own a disproportionately high percent of the country’s mom-and-pop shops, especially in the restaurant industry.

At this point, the aforementioned hard-headed conservatives may accuse me of caring about distribution more than production. Why settle for somewhat-productive mom-and-pop shops when you could get ultra-productive chains like CVS and Walmart? If we’re going for productivity, why not go all the way?

The answer, I think, is political-economic in nature. Socialists may be leading the charge for small business, but small business owners are perhaps the key constituency for capitalism itself. Being a business owner means that you are, by definition, a capitalist; you depend for your livelihood not just on the right to own capital and hire workers, but also on the entire network of trade and markets that supports modern business. Any major shock to that underlying free-market system — or even government policies that increase your costs by a moderate amount — is a threat to your way of life.

And on top of that, your day-to-day experience of life — hiring, firing, buying, selling, and so on — will familiarize you with the basic principles of markets. As a small businessperson, you “eat what you kill” — your survival depends on your own ability and hard work, and there’s no one looking out for you.

Compare that to the experience of being an employee of a large company, where your destiny is controlled by a distant gigantic organization, and your individual initiative may or may not be recognized and rewarded by your boss. In that sort of environment, socialism may start to seem appealing — it’s just replacing one big domineering organization with another, except at least you can vote for the people in the government.

No wonder small businesspeople tend to support pro-business parties. In the U.S., they’re traditionally a key Republican constituency, reflecting the fact that the GOP used to be known as the party of business. In fact, it’s a consistent finding across countries. Malhotra, Margalit, and Shi (2025) crunch a large number of data sources, and emerge with one consistent finding:

We show that this sizable constituency of [small business owners], which is responsible for a substantial share of economic growth and overall employment, systematically leans to the right. This is most notable among business owners that employ other workers. Our findings indicate that this political affiliation is not merely a result of background characteristics that lead people to open or run a business.

Rather, the evidence suggests that experiences associated with running a business— particularly the heightened need to deal with the regulatory state—underlie the greater appeal of parties on the right.

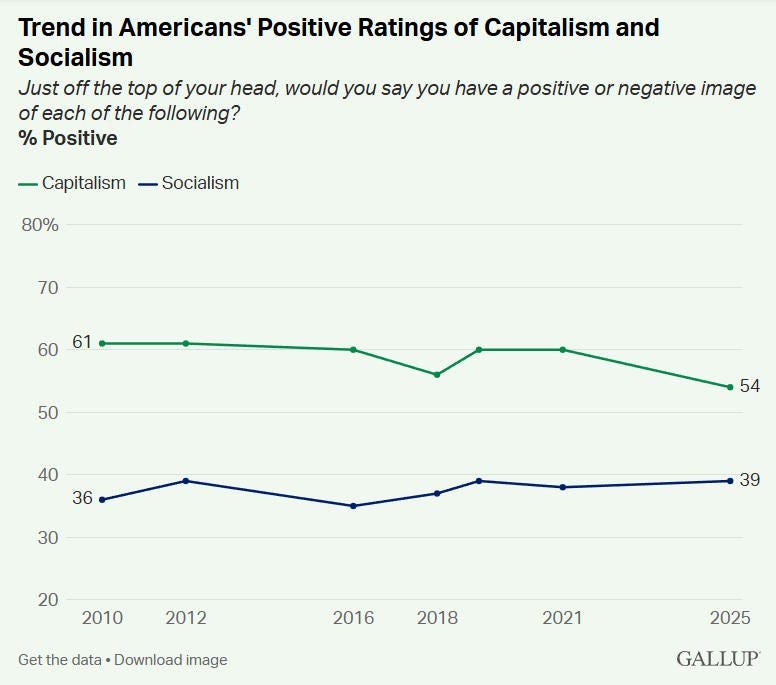

Allowing hyper-efficient chain businesses like Wal-Mart to annihilate independent retail might bring a bit of economic efficiency and some higher profits in the short run, but in the long run, dispossessing the masses of significant capital ownership and disconnecting them from the reality of running a business is probably how you get trends like this one:

Ironically, this means socialists might be hurting their cause in the long term by supporting small business. But in the short term, they might manage to narrow the support gap with the GOP, while devolving capital ownership to a broader base of owners. That might be a compromise worth making, especially in cities like NYC and San Francisco where Republicans are probably not going to be a competitive threat anytime soon.

In the realm of urbanism, too, my bet is that small business owners have a positive effect. Data is more sparse here, but lots of the things that make cities livable — low crime, cheap dense housing, high-quality public transit — also happen to be the very things that bring lots of customers to small businesses’ doors. Small businesses do much better when they have lots of people living nearby, who can easily reach their doors on foot, and who can go outside without being worried about crime. The more that small businesses get strengthened in American cities, I predict, the faster sanity can be restored to urban policy after the missteps of the last few years.

On top of all the political-economic and distributional benefits, having a lot of small independent retail outlets just makes a city really, really nice. I wrote about this back in May:

I’ll just quote myself a little bit:

Although American urbanists usually think in terms of housing density — which is understandable, given the country’s failure to build enough housing — I’ve come to realize the importance of commercial density. Basically, great cities have a lot of shops everywhere…The beauty of Brooklyn’s brownstones, or Paris’ Haussmann apartments, comes in large part from the fact that they’re located near to shops…

When we lament the isolation of the suburbs, we’re not really lamenting low residential density; we’re lamenting the isolation of houses from third spaces where people might meet and mingle. Those third spaces are shops…If you expect citizens to give up the comfort of huge suburban houses and leafy green lawns and move to the city center, they have to be compensated in some way. Having a huge variety of stores and restaurants and bars and cafes within easy walking distance is that compensation.

I’ve also written about how Japan’s strong support for small business is one of the biggest reasons why its cities are such amazing places to live and to visit. You just can’t beat the experience of walking around all those cool little independent restaurants and stores.

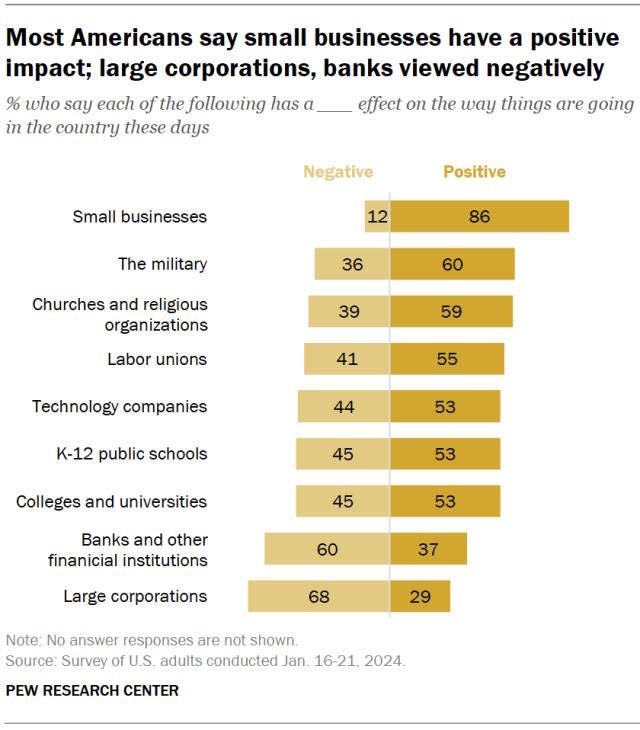

So anyway, I’m not worried about the economic inefficiency of small shops. They bring balance to the political system, they improve the quality of our cities, and they support the great American middle class. No wonder they’re more popular than any other institution in the country:

Mamdani, Lurie, and the other mayors supporting small retail business are doing exactly the right thing. It’s very refreshing to see a sensible urban policy after so many years of destructive nonsense.

Whether small business are good for economic growth overall is a slightly different question. In fact, different studies tend to contradict each other on this point.

And I would also imagine that permit reform and deregulation would make small businesses more productive in the future. I’m not a small business owner, but it seems like the somewhat “fixed costs” of excessive regulations (at least from a waste of time perspective) would negatively affect small businesses even more as there is less business to spread it over.

Another benefit is simply the optionality it gives people for earning a living. Increasingly, whatever your educational background or profession, the two overwhelming career options today seem to be working for a large tech company or becoming an independent content creator (with some obvious exceptions like lawyers and doctors). Running a good ol' small business is a breath of fresh air in the age of digital economy.